Barron's SAT, 26th edition (2012)

Part 3. TACTICS AND PRACTICE: CRITICAL READING

Chapter 5. Common Problems in Grammar and Usage

• Common Problems in Grammar

• Problems with Agreement

• Problems with Case

• Problems Involving Modifiers

• Common Problems in Usage

• Picking Proper Prepositions

COMMON PROBLEMS IN GRAMMAR

Sentence Fragments

What is a sentence fragment? A sentence fragment is a broken chunk of sentence in need of fixing. The poor fractured thing can’t stand alone. In this section, we’ll look at some broken sentences and fix them, too.

Here are the fragments. Let’s examine them one at a time.

When the troll bounced off the bannister.

Muttering over the cauldron.

To harvest mandrakes nocturnally.

In our preparation of the purple potion.

Or lurk beneath the balustrade.

Say the first sentence fragment aloud: “When the troll bounced off the bannister.” Say it again. Do you feel as if something is missing? Do the words trigger questions in your mind? “What?” “What happened?” That’s great. You are reacting to a dependent clause—a clause preceded by a subordinating conjunction, in this case, the conjunction when—that is being treated as if it were a sentence. But it isn’t.

Here are a couple of ways to correct this fragment. You can simply chop off the subordinating conjunction when, leaving yourself with a simple sentence:

The troll bounced off the bannister.

You can also provide the dependent clause with an independent clause to lean on:

When the troll bounced off the bannister, he bowled over the professor of herbology.

The little wizards laughed to see such sport when the troll bounced off the bannister.

Now for the second fragment, “Muttering over the cauldron.” Again, something feels incomplete. This is a phrase, either a participial phrase (a group of related words that functions as an adjective or adverb) or a gerund phrase (a verb form ending in –ing that functions as a noun). These labels do not matter. What matters is that you fix the fragment. It needs a subject; it also needs a complete verb. Here’s the simplest way to repair it.

The witch is muttering over the cauldron.

You’ve added a subject (The witch) and added is to complete the verb (is muttering).

Here’s another:

Muttering over the cauldron is a bad habit that good witches should avoid.

You’ve used Muttering over the cauldron as the subject and added a predicate.

Here’s a third:

Muttering over the cauldron, the witch failed to enunciate the incantation clearly.

You’ve used Muttering over the cauldron as an adjective, modifying the sentence’s subject, witch.

The third fragment again has several fixes. You can turn the infinitive phrase “To harvest mandrakes nocturnally” into a command:

Harvest mandrakes nocturnally! (The professor of herbology does not recommend that you harvest them by day.)

You can provide a simple subject and complete the verb:

We will harvest mandrakes nocturnally.

You can treat “To harvest mandrakes nocturnally” as the subject of your sentence and add a predicate:

To harvest mandrakes nocturnally is a task that only a fearless junior wizard would undertake.

You can also keep “To harvest mandrakes nocturnally” as an infinitive phrase and attach it to an independent clause:

To harvest mandrakes nocturnally, you must wait for a completely moonless night.

The next to last sentence fragment, “In our preparation of the purple potion,” is a prepositional phrase.

To fix it, you can provide a simple subject and create a verb:

We prepared the purple potion.

You can assume an implicit subject (you) and turn it into a command:

Prepare the purple potion!

You can also attach it to an independent clause:

We miscalculated the proportions in our preparation of the purple potion.

The final sentence fragment, “Or lurk beneath the balustrade,” is part of a compound predicate. Take away the initial Or and you have a command:

Lurk beneath the balustrade!

Provide a simple subject and you have a straightforward declarative sentence:

Orcs lurk beneath the balustrade.

Combine the fragment with the other part or parts of the compound predicate, and you have a complete sentence:

Orcs slink around the cellarage or lurk beneath the balustrade.

Here is a question involving a sentence fragment. See whether you can select the correct answer.

Some parts of the following sentence are underlined. The first answer choice, (A), simply repeats the underlined part of the sentence. The other four choices present four alternative ways to phrase the underlined part. Select the answer that produces the most effective sentence, one that is clear and exact. In selecting your choice, be sure that it is standard written English, and that it expresses the meaning of the original sentence.

Example:

J. K. Rowling, a British novelist, whose fame as an innovator in the field of fantasy may come to equal that of J. R. R. Tolkien.

(A) J. K. Rowling, a British novelist, whose fame as an innovator

(B) A British novelist who is famous as an innovator, J. K. Rowling

(C) J. K. Rowling, who is a British novelist and whose fame as an innovator

(D) J. K. Rowling is a British novelist whose fame as an innovator

(E) A British novelist, J. K. Rowling, who is a famous innovator

Did you spot that the original sentence was missing its verb? The sentence’s subject is J. K. Rowling. She is a British novelist. That is the core of the sentence. Everything else in the sentence simply serves to clarify what kind of novelist Rowling is. She is a novelist whose fame may come to equal Tolkien’s fame. The correct answer is Choice D.

Try this second question, also involving a sentence fragment.

The new vacation resort, featuring tropical gardens and man-made lagoons, and overlooks a magnificent white sand beach.

(A) resort, featuring tropical gardens and man-made lagoons, and overlooks a magnificent white sand beach

(B) resort overlooks a magnificent white sand beach, it features tropical gardens and man-made lagoons

(C) resort, featuring tropical gardens and man-made lagoons and overlooking a magnificent white sand beach

(D) resort, featuring tropical gardens and man-made lagoons, overlooks a magnificent white sand beach

(E) resort to feature tropical gardens and man-made lagoons and to overlook a magnificent white sand beach

What makes this a sentence fragment? Note the presence of and just before the verb overlooks. The presence of and immediately before a verb is a sign of a compound predicate, as in the sentence “The cauldron bubbled and overflowed.” (Definition: A compound predicate consists of at least two verbs, linked by and, or, nor, yet, or but, that have a common subject.) But there is only one verb here, not two.

How can you fix this fragment? You can rewrite the sentence, substituting the verb features for the participle featuring so that the sentence has two verbs:

The new vacation resort features tropical gardens and man-made lagoons and overlooks a magnificent white sand beach.

Or, you can simply take away the and. The sentence then would read:

The new vacation resort, featuring tropical gardens and man-made lagoons, overlooks a magnificent white sand beach.

This sentence is grammatically complete. It has a subject, resort, and a verb, overlooks. The bit between the commas (“featuring...lagoons”) simply describes the subject. (It’s called a participial phrase.) The correct answer is Choice D.

The Run-On Sentence

The run-on sentence is a criminal connection operating under several aliases: the comma fault sentence, the comma splice sentence, the fused sentence. Fortunately, there’s no need for you to learn the grammar teachers’ names for these flawed sentences. You just need to know they are flawed.

Here are two run-on sentences. It’s easy to spot the comma fault or comma splice: it’s the one containing the comma.

EXAMPLE 1: The wizards tasted the potion, they found the mixture tasty.

EXAMPLE 2: The troll is very hungry I think he is going to pounce.

The comma splice or comma fault sentence is a sentence in which two independent, self-supporting clauses are improperly connected by a comma. Clearly, the two are in need of a separation if not a divorce. Example 1 above illustrates a comma splice or comma fault. The fused sentence (Example 2) consists of two sentences that run together without benefit of any punctuation at all. Such sentences are definitely not PG (Properly Grammatical).

You can correct run-on sentences in at least four different ways.

1. Use a period, not a comma, at the end of the first independent clause. Begin the second independent clause with a capital letter.

The wizards tasted the potion. They found the mixture tasty.

The troll is very hungry. I think he is going to pounce.

2. Connect the two independent clauses by using a coordinating conjunction.

The wizards tasted the potion, and they found the mixture tasty.

The troll is very hungry, so I think he is going to pounce.

3. Insert a semicolon between two main clauses that are not already connected by a coordinating conjunction.

The wizards tasted the potion; they found the mixture tasty.

The troll is very hungry; I think he is going to pounce.

4. Use a subordinating conjunction to indicate that one of the independent clauses is dependent on the other.

When the wizards tasted the potion, they found the mixture tasty.

Because the troll is very hungry, I think he is going to pounce.

Here is a question involving a run-on sentence. See whether you can select the correct answer.

Some parts of the following sentence are underlined. The first answer choice, (A), simply repeats the underlined part of the sentence. The other four choices present four alternative ways to phrase the underlined part. Select the answer that produces the most effective sentence, one that is clear and exact. In selecting your choice, be sure that it is standard written English, and that it expresses the meaning of the original sentence.

Example:

Many students work after school and on weekends, consequently they do not have much time for doing their homework.

(A) weekends, consequently they do not have

(B) weekends, they do not have

(C) weekends, as a consequence they do not have

(D) weekends, therefore they do not have

(E) weekends; consequently, they do not have

What makes this a run-on sentence? There are two main clauses here, separated by a comma. The rule is, use a comma between main clauses only when they are linked by a coordinating conjunction (and, but, for, or, nor, so, yet). There’s no coordinating conjunction here, so you know the sentence as it stands is wrong. The main clauses here are linked by consequently, which is what grammar teachers call a conjunctive adverb. A rule also covers conjunctive adverbs. That rule is, use a semicolon before a conjunctive adverb set between two main clauses. Only one answer choice uses a semicolon before consequently: the correct answer, Choice E.

PROBLEMS WITH AGREEMENT

Subject–Verb Agreement

The verb and its subject must get along; otherwise, things turn nasty. The rule is that a verb and its subject must agree in person and number. A singular verb must have a singular subject; a plural verb must have a plural subject.

Here are some singular subjects, properly agreeing with their singular verbs:

|

I conjure |

You lurk |

She undulates |

|

I am conjuring |

You are lurking |

He is ogling |

|

I have conjured |

You have lurked |

It has levitated |

Here are the corresponding plural subjects with their plural verbs:

|

We pirouette |

You pillage |

They sulk |

|

We are pirouetting |

You are pillaging |

They are sulking |

|

We have pirouetted |

You have pillaged |

They have sulked |

Normally, it’s simple to match a singular subject with an appropriate singular verb, or a plural subject with a plural verb. However, problems can arise, especially when phrases or parenthetical expressions separate the subject from the verb. Even the rudest intrusion is no reason for the subject and the verb to disagree.

SUBJECT–VERB AGREEMENT

Is the subject singular, or is it plural? Sometimes it’s hard to tell.

It’s hard to tell when lots of words come between the subject and the verb, separating them.

The cost of test prep books, flash cards, and SAT tutoring sessions make DVD prices seem cheap.

What’s the subject? Cost. (It’s what you’re talking about.)

What’s the verb? Make.

Here’s how to check whether things agree. First, cross out everything in between the subject and the verb.

The cost of test prep books, flash cards, and SAT tutoring sessions make DVD prices seem cheap.

Next, read aloud what’s left.

The cost make DVD prices seem cheap.

Does that sound right to you? No. The subject, cost, is singular; the verb should be singular also. The cost makes DVD prices seem cheap.

Note how the following singular subjects agree with their singular verbs.

A cluster of grapes was hanging just out of the fox’s reach.

The elixir in these bottles is brewed from honey and rue.

The dexterity of her long, thin, elegant fingers has improved immeasurably since she began playing the vielle.

The cabin of clay and wattles was built by William Butler Yeats.

Parenthetical expressions are introduced by as well as, with, along with, together with, in addition to, no less than, rather than, like, and similar phrases. Although they come between the subject and the verb, they do not interfere with the subject and verb’s agreement.

The owl together with the pussycat has gone to sea in a beautiful pea-green boat.

The walrus with the carpenter is eating all the oysters.

Dorothy along with the lion, the scarecrow, the woodman, and her little dog Toto is following the yellow brick road.

Berenice as well as Benedick was hidden under the cloak.

The Trojan horse, including the Greek soldiers hidden within it, was hauled through the gates of Troy.

Henbane, rather than hellebore or rue, is the secret ingredient in this potion.

Henbane, in addition to hops, gives the potion a real kick.

I, like the mandrake, am ready to scream.

Likewise, if a clause comes between the subject and its verb, it should not cause them to disagree. A singular subject still takes a singular verb.

The troll who lurched along the corridors was looking for the loo.

The phoenix that arose from the ashes has scattered cinders everywhere.

The way you’re wrestling those alligators is causing them some distress.

A compound subject (two or more nouns or pronouns connected by and) traditionally takes a plural verb.

The walrus and the carpenter were strolling on the strand.

“The King and I,” said Alice, “are on our way to tea.”

However, there are exceptions. If the compound subject refers to a single person or thing, don’t worry that it is made up of multiple nouns. Simply regard it as singular and follow it with a singular verb.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, written by C.S. Lewis, is an admirable tale.

The Eagle and Child is a pub in Oxford where Lewis and Tolkien regularly sampled the admirable ale.

Green eggs and ham was our family’s favorite breakfast every St. Patrick’s Day.

The King and I is a musical comedy.

Frodo’s guide and betrayer literally bites the hand that feeds him. (Both guide and betrayer refer to the same creature, Gollum.)

(Note that the title of a work of art—a novel, poem, painting, play, opera, ballet, statue—always takes a singular verb, even if the title contains a plural subject. The Burghers of Calais is a statue by Rodin. The burgers of Burger King are whoppers.)

Some words are inherently singular. In American English, collective nouns like team, community, jury, swarm, entourage, and so on are customarily treated as singular.

The croquet team is playing brilliantly, don’t you think?

The community of swamp dwellers has elected Pogo president.

The jury was convinced that Alice should be decapitated.

A swarm of bees is dive-bombing Willie Yeats.

My entourage of sycophants fawns on me in a most satisfying fashion.

However, when a collective noun is used to refer to individual members of a group, it is considered a plural noun.

The jury were unable to reach a verdict. (The individual jurors could not come to a decision.)

I hate it when my entourage of sycophants compete with one another for my attention. (This sentence is technically correct. However, it calls excessive attention to its correctness. In real life, you’d want to rewrite it. Here’s one possible revision: I hate it when my hangers-on compete with one another for my attention.)

Sometimes the article used with a collective noun is a clue to whether the verb is singular or plural. The expressions the number and the variety generally are regarded as singular and take a singular verb. The expressions a numberand a variety generally are regarded as plural and take a plural verb.

The number of angels able to dance on the head of a pin is limited by Fire Department regulations.

A number of angels able to dance on the head of a pin have been booked to perform at Radio City Music Hall.

The variety of potions concocted by the junior wizards is indescribable.

A variety of noises in the night have alarmed the palace guard. (Has Imogen been serenading Peregrine again?)

Some nouns look plural but refer to something singular. These nouns take singular verbs. Consider billiards, checkers, and dominoes (the game, not the pieces). Each is an individual game. What about astrophysics, economics, ethics, linguistics, mathematics, politics, statistics (the field as a whole, not any specific figures), and thermodynamics? Each is an individual discipline or organized body of knowledge. What about measles, mumps, and rickets?Each is an individual disease. Other camouflaged singular nouns are customs (as in baggage inspections at borders), molasses, news, and summons.

While dominoes is Dominick’s favorite pastime, billiards is Benedick’s.

The molasses in the potion disguises the taste of garlic and hellebore.

Rickets is endemic in trolls because of their inadequate exposure to sunlight. (Trolls who get adequate exposure to sunlight suffer instead from petrification.)

This summons to a midnight assignation was from Sybilla, not from Berenice.

Some plural nouns actually name single things that are made of two connected parts: eyeglasses, knickers, pliers, scissors, sunglasses, tights, tongs, trousers, tweezers. Don’t let this confuse you. Just match them up with plural verbs.

Imogen’s knickers are in a twist.

Peregrine’s sunglasses are in the Lost and Found.

Watch out, however, when these plural nouns crop up in the phrase “a pair of....” The scissors are on the escritoire, but a pair of scissors is on the writing desk.

Watch out, also, when a sentence begins with here or there. In such cases, the subject of the verb follows the verb in the sentence.

There are many angels dancing on the head of this pin. [Angels is the subject of the verb are.]

Here is the pellet with the poison. [Pellet is the subject of the verb is.]

In the wizard’s library there exist many unusual spelling books. [Books is the subject of the verb exist.]

Somewhere over the rainbow there lies the land of Oz. [Land is the subject of the verb lies.]

Likewise, watch out for sentences whose word order is inverted, so that the verb precedes the subject. In such cases, your mission is to find the actual subject.

Among the greatest treasures of all the realms is the cloak of invisibility.

Beyond the reckoning of man are the workings of a wizard’s mind.

(An even greater mystery to men are the workings of a woman’s mind....)

SUBJECT–VERB AGREEMENT

Is the subject singular, or is it plural? Sometimes it’s hard to tell.

It’s hard to tell when the subject follows the verb.

In front of the main library, an impressive building that faces Fifth Avenue, stands two marble lions.

What’s the subject? Two marble lions. (They’re what you’re talking about.)

Where’s the subject? At the end of the sentence, after the verb.

What’s the verb? Stands.

Here’s how to check whether things agree. First, reverse the subject and verb, so that they’re in the normal order.

Two marble lions stands.

Next, read that aloud. Does that sound right to you? No. The subject, lions, is plural; the verb should be plural also. One marble lion stands; two marble lions stand.

Finally, substitute the correct verb form in the original sentence.

In front of the main library, an impressive building that faces Fifth Avenue, stand two marble lions.

Here is a question involving subject–verb agreement.

The following sentence may contain an error in grammar, usage, choice of words, or idioms. Either there is just one error in a sentence or the sentence is correct. Some words or phrases are underlined and lettered; everything else in the sentence is correct.

If an underlined word or phrase is incorrect, choose that letter; if the sentence is correct, select No error.

Example:

![]() mathematics and language skills

mathematics and language skills ![]() third grade and eighth grade

third grade and eighth grade ![]() in high school.

in high school. ![]()

Do not let yourself be fooled by nouns or pronouns that come between the subject and the verb. The subject of this sentence is not the plural noun skills. It is the singular noun, proficiency. The verb should be singular as well. The answer containing the subject–verb agreement error is Choice B. To correct the error, substitute is for are.

Pronoun–Verb Agreement

Watch out for errors in agreement between pronouns and verbs. (A pronoun is not a noun that has lost its amateur standing. Instead, it’s a last-minute substitute, called upon to stand in for a noun that’s overworked.) You already know the basic pronouns: I, you, he, she, it, we, they and their various forms. Here is an additional bunch of singular pronouns that, when used as subjects, typically team up with singular verbs.

Each of the songs Imogen sang was off-key. (Was that why her knickers were in a twist?)

Either of the potions packs a punch.

Neither of the orcs packs a lunch. (But, then, neither of the orcs is a vegetarian).

Someone in my entourage has been nibbling my chocolates.

Does anyone who is anyone go to Innisfree nowadays?

Everything is up to date in Kansas City.

Somebody loves Imogen; she wonders who.

Nobody loves the troll. (At least, no one admits to loving the troll. Everybody is much too shy.)

Does everyone really love Raymond?

Exception: Although singular subjects linked by either...or or neither...nor typically team up with singular verbs, a different rule applies when one subject is singular and one is plural. In such cases, proximity matters: the verb agrees with the subject nearest to it. (This rule also holds true when singular and plural subjects are linked by the correlative conjunctions not only...but also and not...but.)

Either the troll or the orcs have broken the balustrade.

Either the hobbits or the elf has hidden the wizard’s pipe.

Neither the junior witches nor the professor of herbology has come up with a cure for warts.

Neither Dorothy nor her three companions were happy about carrying Toto everywhere.

Not only the oysters but also the walrus was eager to go for a stroll.

Not only Berenice but also Benedick and the troll have hidden under the cloak of invisibility.

Oddly enough, not the carpenter but the oysters were consumed by a desire to go for a stroll.

Not the elves but the dwarf enjoys messing about in caves.

The words few, many, and several are plural; they take a plural verb.

Many are cold, but few are frozen.

Several are decidedly lukewarm.

Here is a question involving pronoun–verb agreement.

The following sentence may contain an error in grammar, usage, choice of words, or idioms. Either there is just one error in a sentence or the sentence is correct. Some words or phrases are underlined and lettered; everything else in the sentence is correct.

If an underlined word or phrase is incorrect, choose that letter; if the sentence is correct, select No error.

Example:

![]() the President nor the members of his Cabinet

the President nor the members of his Cabinet ![]() the reporter’s account of dissension

the reporter’s account of dissension ![]() their ranks.

their ranks. ![]()

Here we have one subject that is singular (President) and one that is plural (members). In such cases, the verb agrees with the subject nearest to it. Members is plural; therefore, the verb should be plural as well. Substitute were for was. The correct answer is Choice B.

Pronoun–Antecedent Agreement

A pronoun must agree with its antecedent in person, number, and gender. (The antecedent is the noun or pronoun to which the pronoun refers, or possibly defers.) Such a degree of agreement is unlikely, but in grammar (almost) all things are possible.

The munchkins welcomed Dorothy as she arrived in Munchkinland. (The antecedent Dorothy is a third person singular feminine noun; she is the third person singular feminine pronoun.)

Sometimes the antecedent is an indefinite singular pronoun: any, anybody, anyone, each, either, every, everybody, everyone, neither, nobody, no one, somebody, or someone. If so, the pronoun should be singular.

Neither of the twins is wearing his propeller beanie.

Each of the bronco-busters was assigned his or her own horse.

Anybody with any sense would refrain from serenading his inamorata on television.

When the antecedent is compound (two or more nouns or pronouns connected by and), the pronoun should be plural.

The walrus and the carpenter relished their outing with the oysters.

The walrus always takes salt in his tea.

Christopher Robin and I always have honey in ours.

You and your nasty little dog will get yours someday!

When the antecedent is part of an either...or or neither...nor statement, the pronoun will find it most politic to agree with the nearer antecedent.

Either Sybilla or Berenice always has the troll on her mind. (Actually, they both do, but in different ways.)

[Given the either...or construction, you need to check which antecedent is nearer to the pronoun. The ever-feminine, highly singular Berenice is; therefore, the correct pronoun is her rather than their.]

Neither the professor of herbology nor the junior wizards have finished digging up their mandrake roots. [Wizards is closer to their.]

Neither the hobbits nor the wizard has eaten all his mushrooms. [Wizard is closer to his.]

Here is a question involving pronoun–antecedent agreement.

The following sentence may contain an error in grammar, usage, choice of words, or idioms. Either there is just one error in a sentence or the sentence is correct. Some words or phrases are underlined and lettered; everything else in the sentence is correct.

If an underlined word or phrase is incorrect, choose that letter; if the sentence is correct, select No error.

Example:

Admirers of the vocal ensemble Chanticleer ![]() over the years whether the group, known for

over the years whether the group, known for ![]() mastery of Gregorian chant, might have abandoned its

mastery of Gregorian chant, might have abandoned its ![]() early music

early music ![]() new musical paths.

new musical paths. ![]()

The error here is in Choice B. The sentence is talking about a group. Is the group known for their mastery or for its mastery? Group is a collective noun. In American English collective nouns are usually treated as singular and take singular pronouns. Is that the case here? Yes. How can you be sure? Later in the sentence, a second pronoun appears: its. This pronoun refers back to the same noun: group. Its is not underlined. Therefore, by definition, the singular pronoun must be correct.

In solving error identification questions, remember that anything not underlined in the sentence is correct.

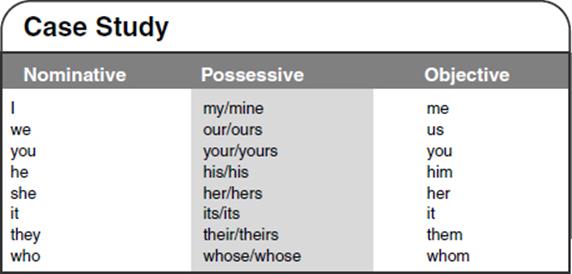

PROBLEMS WITH CASE

Now to get down to cases. In the English language, there are three: nominative (sometimes called subjective), possessive, and objective. Cases are special forms of words that signal how these words function in sentences. Most nouns, many indefinite pronouns, and a couple of personal pronouns reveal little about themselves: they have special case forms only for the possessive case (Berenice’s cauldron, the potion’s pungency, its flavor, your tastebuds, anyone’s guess, nobody’s sweetheart). Several pronouns, however, reveal much more, as the following chart demonstrates.

The Nominative Case: I, we, he, she, it, they, you, who

The nominative case signals that the pronoun involved is functioning as the subject of a verb or as a subject complement.

Ludovic and I purloined the Grey Poupon. [subject of verb]

The only contestants still tossing gnomes were Berenice and he. [subject complement]

The eventual winners—he and she—each received a keg of ale. [As used here, he and she are appositives—nouns or pronouns set beside another noun or noun substitute to explain or identify it. Here, they identify the subject, winners.]

Sir Bedivere unhorsed the knight who had debagged Sir Caradoc. [subject in clause]

The Possessive Case: mine, ours, his, hers, theirs, yours; my, our, his, her, its, their, your, whose

The possessive case signals ownership. Two-year-olds have an inherent understanding of the possessive: Mine!

Drink to me only with thine eyes, and I will pledge with mine.

Please remember that the walrus takes only salt in his tea, while Christopher Robin and I prefer honey in ours, and the Duchess enjoys a drop of Drambuie in hers.

Ludovic put henbane in whose tea?

The possessive case also serves to indicate that a quality belongs to or is characteristic of someone or something.

Her long, thin, elegant fingers once again demonstrated their dexterity.

The troll rebounded at Berenice but failed to shake her composure.

A noun or pronoun immediately preceding a gerund (that is, a verbal that ends in -ing and acts like a noun) is in the possessive case.

The troll’s bouncing into the bannister creates problems for passersby on the staircase. [Troll’s immediately precedes the gerund bouncing.]

The troll would enjoy his bouncing more if Sybilla rather than Berenice caught him on the rebound. [His immediately precedes the gerund bouncing.]

The Objective Case

Traditionally, the objective case indicates that a noun or pronoun receives whatever action is taking place. A pronoun in the objective case can serve as a direct object of a transitive verb, as an indirect object, as an object of a preposition, or, oddly enough, as the subject or object of an infinitive.

Berenice bounced him off the bannister again. [direct object]

The walrus gave them no chance to refuse his invitation to go for a stroll. [indirect object]

William Yeats, by whom the small cabin was built, was a better poet than carpenter. [object of preposition within a clause]

Peregrine expected her to serenade him. [subject and object of the infinitive to serenade.]

Be careful to use objective pronouns as objects of prepositions.

Everyone loves Raymond except Berenice and me.

Between you and me, I’m becoming suspicious of Sybilla and him.

Here are a couple of questions with problems involving case.

The following sentences may contain an error in grammar, usage, choice of words, or idioms. Either there is just one error in a sentence or the sentence is correct. Some words or phrases are underlined and lettered; everything else in the sentence is correct.

If an underlined word or phrase is incorrect, choose that letter; if the sentence is correct, select No error.

Example:

All of the flood victims except Lloyd and ![]() the settlement

the settlement ![]() the insurance company.

the insurance company. ![]()

The object of the preposition except should be in the objective case. Change I to me. The error in the sentence is Choice A.

Because ![]() jurors and

jurors and ![]() interpretation of the judge’s instructions, they asked for a clarification.

interpretation of the judge’s instructions, they asked for a clarification. ![]()

Here we have a compound subject. The subject of the initial clause (“Because...instructions”) should be in the nominative case. Change her to she. The correct answer is Choice B.

Many confusions about case involve compound subjects (“the other jurors and she”) or compound objects of prepositions (“except Lloyd and me”). If you are having trouble recognizing which form of a pronoun to use, try reversing the noun-pronoun word order, or even dropping the noun. For example, instead of saying “Because the other jurors and her differed,” try saying “Because her and the other jurors differed.” Or simply say, “Because her differed.” Does the pronoun sound odd to you? It should. When that happens, check whether the pronoun is in the right case.

PROBLEMS INVOLVING MODIFIERS

Unclear Placement of Modifiers

Location, location, location. In general, adjectives, adverbs, adjective phrases, adverbial phrases, adjective clauses, and adverbial clauses need to be close to the word they modify. If these modifiers are separated from the word they modify, confusion may set in.

Some specific rules to apply:

1 Place the adverbs only, almost, even, ever, just, merely, and scarcely right next to the word they modify.

Ambiguous: The walrus almost ate all the oysters. (Did he just chew them up and spit them out without swallowing?)

Clear: The walrus ate almost all the oysters. (He left a few for the carpenter.)

Ambiguous: This elephant only costs peanuts.

Clear: Only this elephant costs peanuts. (The other elephants are traded for papayas and pomegranates.)

Clear: This elephant costs only peanuts. (What a cheap price for such a princely pachyderm!)

2 Place phrases close to the word they modify.

Unclear: The advertisement stated that a used cauldron was wanted by an elderly witch with stubby legs. (Obviously, the advertisement was not written to reveal the lady’s physical oddity.)

Clear: The advertisement stated that a used cauldron with stubby legs was wanted by an elderly witch.

3 Place adjective clauses near the words they modify.

Misplaced: The owl and the pussycat bought a wedding ring from the pig which cost one shilling.

Clear: The owl and the pussycat bought a wedding ring which cost one shilling from the pig.

4 Words that may modify either a preceding or following word are called squinting modifiers. (They look both ways at once; no wonder they’re walleyed.) To correct the ambiguity, move the modifier so that its relationship to one word is clear.

Squinting: Peregrine said that if Imogen refused to quit caterwauling beneath his balcony in two minutes he would send for the troll.

Clear: Peregrine said that he would send for the troll if Imogen refused to quit caterwauling beneath his balcony in two minutes.

Clear: Peregrine said that he would send for the troll in two minutes if Imogen refused to quit caterwauling beneath his balcony.

Squinting: The oysters agreed on Sunday to go for a stroll with the walrus.

Clear: On Sunday, the oysters agreed to go for a stroll with the walrus.

Clear: The oysters agreed to go for a stroll with the walrus on Sunday.

Dangling Modifiers

When modifying phrases or clauses precede the main clause of a sentence, position is everything. These modifiers should come directly before the subject of the main clause and should clearly refer to that subject. If the modifiers foolishly hang out in the wrong part of the sentence, they may wind up dangling there making no sense at all.

To correct a dangling modifier, rearrange the words of the sentence to bring together the subject and its wayward modifier. You may need to add a few words to the sentence to clarify its meaning.

Dangling Participle: Walking down the Yellow Brick Road, the Castle of Great Oz was seen. (Did you ever see a castle walking? Well, I didn’t.)

Corrected: Walking down the Yellow Brick Road, Dorothy and her companions saw the Castle of Great Oz. (The participle walking immediately precedes the subject of the main clause Dorothy and her companions.)

In the preceding example, the participial phrase comes at the beginning of the sentence. In the example below, the participial phrase follows the sentence base.

Dangling Participle: The time passed very enjoyably, singing songs and romping with Toto. (Who’s that romping with Toto?)

Corrected: They passed the time very enjoyably, singing songs and romping with Toto.

Watch out for dangling phrases containing gerunds or infinitives.

Dangling Phrase Containing Gerund: Upon hearing the report that a troll had been found in the cellars, the building was cleared. (Again, ask yourself who heard the report. Even though the building was a school for wizards, its walls did not have ears.)

Corrected: Upon hearing the report that a troll had been found in the cellars, the headmaster cleared the building.

Dangling Phrase Containing Infinitive: Unable to defeat the Trojans in open battle, a trick was resorted to by the Greeks.

Corrected: Unable to defeat the Trojans in open battle, the Greeks resorted to a trick.

Be careful when you create elliptical constructions (ones in which some words are implied rather than explicitly stated) that you don’t cut out so many words that you wind up with a dangling elliptical adverb clause.

Dangling Elliptical Construction: When presented with the potion, not one drop was drunk.

Corrected: When presented with the potion, nobody drank a drop.

Corrected: When they were presented with the potion, not one drop was drunk.

Yet Another Dangling Elliptical Construction: Although only a small dog, Dorothy found Toto a big responsibility.

Corrected: Although Toto was only a small dog, Dorothy found him a big responsibility.

Here are a couple of questions involving misplaced modifiers:

Some parts of the following sentences are underlined. The first answer choice, (A), simply repeats the underlined part of the sentence. The other four choices present four alternative ways to phrase the underlined part. Select the answer that produces the most effective sentence, one that is clear and exact. In selecting your choice, be sure that it is standard written English, and that it expresses the meaning of the original sentence.

Example:

Returning to Harvard after three decades, the campus seemed much less cheery to Sharon than it had been when she was studying there.

(A) Returning to Harvard after three decades, the campus seemed much less cheery to Sharon

(B) After Sharon returned to Harvard in three decades, it seemed a much less cheery campus to her

(C) Having returned to Harvard after three decades, it seemed a much less cheery campus to Sharon

(D) When Sharon returned to Harvard after three decades, she thought the campus much less cheery

(E) Sharon returned to Harvard after three decades, and then she thought the campus much less cheery

Did you recognize that the original sentence contains a dangling modifier? Clearly, the campus did not return to Harvard; Sharon returned to Harvard. By replacing the participial phrase with a subordinate clause (“When...decades”) and by making she the subject of the sentence, Choice D corrects the error in the original sentence.

Try this second question, also involving a dangling modifier.

Having drafted the museum floor plan with exceptional care, that the planning commission rejected his design upset the architect greatly.

(A) that the planning commission rejected his design upset the architect greatly

(B) the planning commission’s rejection of his design caused the architect a great upset

(C) the architect found the planning commission’s rejection of his design greatly upsetting

(D) the architect was greatly upset about the planning commission rejecting his design

(E) the architect’s upset at the planning commission’s rejection of his design was great

Again, ask yourself who drafted the museum floor plan. Clearly, it was the architect. Architect, therefore, must be the sentence’s subject. The correct answer must be either Choice C or Choice D. Choice D, however, introduces a fresh error. The phrase “rejecting his design” is a gerund. As a rule, you should use the possessive case before a gerund: to be correct, the sentence would have to read “the architect was greatly upset about the planning commission’s rejecting his design.” Choice D, therefore, is incorrect. The correct answer is Choice C.

COMMON PROBLEMS IN USAGE

Words Often Misused or Confused

Errors in diction—that is, choice of words—frequently crop up on the Writing Section of the SAT. Here are some of the most common diction errors to watch for:

accept/except. These two words are often confused. Accept means to take or receive; to give a favorable response to something; to regard as proper. Except, when used as a verb, means to preclude or exclude. (Except may also be used as a preposition or a conjunction.)

Benedick will accept the gnome-tossing award on Berenice’s behalf.

The necromancer’s deeds were so nefarious that he was excepted from the general pardon. In other words, they pardoned everyone except him.

affect/effect. Affect, used as a verb, means to influence or impress, and to feign or assume. Effect, used as a verb, means to cause or bring about.

When Berenice bounced the troll against the balustrade, she effected a major change in his behavior.

The blow affected him conspicuously, denting his skull and his complacency.

To cover her embarrassment about the brawl, Berenice affected an air of nonchalance.

Effect and affect are also used as nouns. Effect as a noun means result, purpose, or influence. Affect, a much less common noun, is a psychological term referring to an observed emotional response.

Did being bounced against the balustrade have a beneficial effect on the troll?

The troll’s affect was flat. So was his skull.

aggravate. Aggravate means to worsen or exacerbate. Do not use it as a synonym for annoy or irritate.

The orc will aggravate his condition if he tries to toss any gnomes so soon after his operation.

The professor of herbology was irritated [not aggravated] by the mandrakes’ screams.

ain’t. Ain’t is nonstandard. Avoid it.

already/all ready. These expressions are frequently confused. Already means previously; all ready means completely prepared.

The mandrakes have already been dug up.

Now the mandrakes are all ready to be replanted.

alright. Use all right instead of the misspelling alright. (Is that all right with you?)

altogether/all together. All together means as a group. Altogether means entirely, completely.

The walrus waited until the oysters were all together on the beach before he ate them.

There was altogether too much sand in those oysters.

among/between. Use among when you are discussing more than two persons or things; between when you are limiting yourself to only two persons or things.

The oysters were divided among the walrus, the carpenter, and the troll.

The relationship between Berenice and Benedick has always been a bit kinky.

amount/number. Use amount when you are referring to mass, bulk, or quantity. Use number when the quantity can be counted.

We were amazed by the amount of henbane the troll could eat without getting sick.

We were amazed by the number of hens the troll could eat without getting sick.

and etc. The and is unnecessary. Cut it.

being as/being that. These phrases are nonstandard; avoid them. Use since or because

beside/besides. These words are often confused. Beside is always a preposition. It means “next to” or, sometimes, “apart from.” Watch out for possible ambiguities or ambiguous possibilities. “No one was seated at the Round Table beside Sir Bedivere” has two possible meanings.

No one was seated at the Round Table beside Sir Bedivere. [There were empty seats on either side of Bedivere; however, Sir Kay, Sir Gawain, and Sir Galahad were sitting across from him on the other side of the table.]

No one was seated at the Round Table beside Sir Bedivere. [Poor Bedivere was all alone.]

Besides, when used as a preposition, means “in addition to” or “other than.”

Besides oysters, the walrus and the carpenter have eaten countless cockles and mussels and clams.

Who will go to the bear-baiting besides Berenice and Benedick?

Besides also is used as an adverb. At such times, it means moreover or also.

The troll broke the balustrade—and the newel post besides.

between. See among.

but what. Avoid this phrase. Use that instead.

Wrong: Imogen could not believe but what Peregrine would overlook their assignation.

Better: Imogen could not believe that Peregrine would overlook their assignation.

can’t hardly/can’t scarcely. You have just encountered the dreaded double negative. (I can hardly believe anyone writes that way, can you?) Use can hardly or can scarcely.

conscious/conscience. Do not confuse these words. Conscious, an adjective, means aware and alert; it also means deliberate.

Don’t talk to Berenice before she’s had her morning cup of coffee; she isn’t really conscious until she has some caffeine in her system.

When Ludovic laced the professor’s potion with strychnine, was he making a conscious attempt to kill the prof?

Conscience, a noun, means one’s sense of right and wrong.

Don’t bother appealing to the orc’s conscience: he has none.

could of. This phrase is nonstandard. Substitute could have.

different from/different than. Current usage accepts both forms; however, a Google check indicates that different from is the more popular usage.

effect. See affect.

farther/further. Some writers use the adverb farther when discussing physical or spatial distances; further, when discussing quantities. Most use them interchangeably. The adjective further is a synonym for additional.

Benedick has given up gnome-tossing contests because Berenice always tosses her gnomes yards farther than Benedick can toss his. [adverb]

This elixir is further enriched by abundant infusions of henbane and hellebore. [adverb]

Stay tuned for further announcements of the latest results in today’s gnome-tossing state finals. [adjective]

fewer/less. Use fewer with things that you can count (one hippogriff, two hippogriffs...); less, with things that you cannot count but can measure in other ways.

“There are fewer oysters on the beach today than yesterday, I fear. How sad!” said the carpenter, and brushed away a tear.

Berenice should pay less attention to troll tossing and more to divination and elementary herbology.

former/latter. Use former and latter only when you discuss two items. (Former refers to the first item in a series of two; latter, to the second.) When you discuss a series of three or more items, use first and last

Who was madder, the March Hare or the Hatter? Was it the former, or was it the latter (the Hatter)?

Though the spoon, the knife, and the fork each asked the dish to elope, everyone knows the dish ran away with the first.

further. See farther.

had of/had have. These phrases are nonstandard. Substitute had.

|

Do Not Write: |

If Benedick had of [nonstandard] tossed the gnome a foot farther, he could of [also nonstandard] won the contest. |

|

Write: |

If Benedick had tossed the gnome a foot farther, he could have won the contest. |

hanged/hung. Both words are the past participle of the verb hang. However, in writing formal English, use hanged when you are discussing someone’s execution; use hung when you are talking about the suspension of an object.

Ludovic objected to being hanged at dawn, saying he wouldn’t get up that early for anybody’s execution, much less his own.

The stockings were hung from the chimney with care.

hardly/scarcely. These words are sufficiently negative on their own that you don’t need any extra negatives (like not, nothing, or without) to get your point across. In fact, if you do add that extra not or nothing, you’ve perpetrated the dreaded double negative.

|

Do Not Write: |

The walrus couldn’t hardly eat another bite. |

|

Write: |

The walrus could hardly eat another bite. |

|

Do Not Write: |

Compared to the walrus, the carpenter ate hardly nothing. |

|

Write: |

Compared to the walrus, the carpenter ate hardly anything (or anyone). |

|

Do Not Write: |

The troll pounced without scarcely a moment’s hesitation. |

|

Write: |

The troll pounced with scarcely a moment’s hesitation. |

imply/infer. People often use these words interchangeably to mean hint at or suggest. However, imply and infer have precise meanings that you need to tell apart. Imply means to suggest something without coming right out and saying it. Infer means to draw a conclusion, basing it on some sort of evidence.

When Auntie Em said, “My! That’s a big piece of pie, young lady,” did she mean to imply that Dorothy was being a glutton in taking such a huge slice?

Dorothy inferred from Auntie Em’s comment that she’d better not ask for a second piece.

Imogen inferred from the fresh dent in the troll’s skull that Berenice had been bouncing him off the balustrade again.

in back of. Avoid this expression. Use behind instead.

incredible/incredulous. Incredible means unbelievable, too improbable to be believed. Incredulous means doubtful or skeptical, unwilling to believe.

When Ludovic saw Berenice juggling three trolls in the air, he was amazed at her incredible strength.

Do you believe all this jabber about Berenice’s strength, or are you incredulous?

irregardless. This nonstandard usage particularly irritates graders. Use regardless instead.

kind of/sort of. In writing formal prose, avoid using these phrases adverbially (that is, with the meaning of somewhat or to a degree, as in “kind of bashful” or “sort of infatuated.”) Use words like quite, rather, or somewhat instead.

|

Informal: |

Dorothy was kind of annoyed by the wizard’s obfuscations. |

|

Approved: |

Dorothy was quite annoyed by the wizard’s obfuscations. |

kind of a/sort of a. In writing formal prose, cut out the a.

|

Do Not Write: |

Sybilla seldom brews this kind of a potion. |

|

Write: |

Sybilla seldom brews this kind of potion. |

last/latter. See former.

later/latter. Use later when you’re talking about time (you’ll do it sooner or later). Use latter when you’re talking about the second one of a group of two (not the former—that comes first—but the latter).

Every night Imogen stays up later and later serenading Peregrine.

Berenice tossed both the troll and a gnome. The latter bounced farther.

learn/teach. Learn means to get knowledge; teach means to instruct, to give knowledge or information. Don’t confuse the two.

|

Incorrect: |

I’ll learn you, you stupid troll! |

|

Correct: |

I’ll teach you, you obtuse orc! |

leave/let. Leave primarily means to depart; let, to permit. Don’t confuse them. (Leave, when followed by an object and an infinitive or a participial phrase, as in “Leave him to do his worst” or “Leave it to Beaver,” has other meanings. Consult an unabridged dictionary.)

|

Incorrect: |

Leave me go, Berenice. |

|

Correct: |

Let me go, Berenice. Please let me leave. |

less. See fewer.

liable to/likely to. Likely to refers simply to probability. When speaking informally, people are likely to use liable to in place of likely to. However, in formal writing, liable to conveys a sense of possible harm or misfortune.

|

Informal: |

The owl and the pussycat are liable to go for a sail. [This is a simple statement of probability. More formally, you would write “The owl and the pussycat are likely to go for a sail.”] |

|

Preferable: |

The beautiful but leaky pea-green boat is liable to sink. [This conveys a sense of likely danger.] |

loose/lose. These are not synonyms. Loose is primarily an adjective meaning free or inexact or not firmly fastened (“a loose prisoner,” “a loose translation,” “a loose tooth”). As a verb, loose means to set free or let fly.

Loose the elephants!

The elf loosed his arrows at the orcs.

Lose is always a verb.

If the elf loses any more arrows in the bushes, he won’t have any left to loose at the orcs.

Hey, baby, lose the sidekick, and you and I can have a good time.

me and. Unacceptable as part of a compound subject.

|

Nonstandard: |

Me and Berenice can beat any three trolls in the house. |

|

Preferred: |

Berenice and I can beat any three trolls in the house. (Actually, Berenice can beat them perfectly well without any help from me.) |

number. See amount.

of. Don’t write of in place of have in the expressions could have, would have, should have, must have, and so on.

off of. In formal writing, the of is superfluous. Cut it.

|

Incorrect: |

The troll bounced off of the bannister. |

|

Correct: |

The troll bounced off the bannister. |

principal/principle. Do not confuse the adjective principal, meaning chief, with the noun principle, a rule or law.

Berenice’s principal principle (that is, her chief rule of conduct) is “The bigger they are, the harder they bounce.”

In a few cases, principal is used as a noun: the principal of a loan (the main sum you borrowed); the principal in a transaction (the chief person involved in the deal); the principal of a school (originally the head teacher). Don’t worry about these instances. If you can substitute the word rule for the noun in your sentence, then the word you want is principle.

raise/rise. Do not confuse the verb raise (raised, raising) with rise (rose, risen, rising). Raise means to increase, to lift up, to collect, or to nurture. It is transitive (it takes an object). Rise means to ascend, to get up, or to grow. It is intransitive (no objects need apply).

|

Incorrect: |

They are rising the portcullis. |

|

Correct: |

They are raising the portcullis. [The object is portcullis, a most heavy object indeed.] |

|

Incorrect: |

The sun raised over the battlements. |

|

Correct: |

The sun rose over the battlements. |

real. This word is an adjective meaning genuine or concrete. Do not use it as an adverb meaning very or extremely.

|

Too Informal: |

This is a real weird list of illustrative sentences. |

|

Preferable: |

This is a really weird list of illustrative sentences. |

|

Even Better: |

This is an extremely weird list of illustrative sentences. |

the reason is because. This expression is ungrammatical. If you decide to use the phrase the reason is, follow it with a concise statement of the reason, not with a because clause.

|

Incorrect: |

The reason the oysters failed to answer is because the walrus and the carpenter had eaten every one. |

|

Correct But Wordy: |

The reason the oysters failed to answer is that the walrus and the carpenter had eaten every one. |

|

Correct & Concise: |

The oysters failed to answer because the walrus and the carpenter had eaten every one. |

same. Lawyers and writers of commercial documents sometimes use same as a pronoun. In writing essays, use the pronouns it, them, this, that in its place.

|

Incorrect: |

I have received your billet-doux and will answer same once my messenger owl returns home. |

|

Correct: |

I have received your billet-doux and will answer it once my messenger owl returns home. |

scarcely. See hardly.

sort of. See kind of.

teach. See learn.

try and. Avoid this phrase. Use try to in its place.

|

Incorrect: |

We must try and destroy the Ring of the Enemy. |

|

Correct: |

We must try to destroy the Ring of the Enemy. |

unique. The adjective unique describes something that is the only one of its kind. Don’t qualify this adjective by more, most, less, least, slightly, or a little bit. It’s just as illogical to label something a little bit unique as it is to describe someone as a little bit pregnant.

|

Incorrect: |

Only the One Ring has the power to rule elves, dwarfs, and mortal men. It is most unique. |

|

Correct: |

Only the One Ring has the power to rule elves, dwarfs, and mortal men. It is unique. |

PICKING PROPER PREPOSITIONS

Occasionally, you may get back papers from your teachers with certain expressions labeled “unidiomatic.” Often these errors involve prepositions. When you are in doubt about what preposition to use after a particular word, look up that word in an unabridged dictionary. Meanwhile, look over the list below to see which preposition customarily accompanies the following words.

accede to

Sybilla graciously acceded to Peregrine’s request to compose a villanelle.

according to

According to Abelard, Esperanto is the language of love.

accuse of

Berenice vociferously accused the troll of borrowing her leotard.

addicted to

The professor of herbology is reputedly addicted to comfrey tea.

adhere to

Muttering the conjunction spell under his breath, the wizard adhered the brigand to the bottom of the balcony.

adverse to

Imogen is adverse to Peregrine’s writing verse to other women.

afflict with

The wizard afflicted the brigand with borborygmus and boils.

agree on (come to terms)

The owl and the pussycat could not agree on what color to repaint their pea-green boat.

agree with (suit; be similar to; be consistent with)

Burping miserably, the carpenter confessed that a diet of oysters did not agree with him.

agreeable to

The troll found tiddlywinks an occupation most agreeable to his tastes.

amazement at

Imagine Imogen’s amazement at discovering the brigand dangling from the bottom of the balcony!

amenable to

Excessively amenable to persuasion, Imogen is the archetypal girl who can’t say no.

appetite for

The walrus had an insatiable appetite for oysters.

appreciation of

The troll’s appreciation of the fine points of pillaging was sadly limited.

aside from

The professor of potions had run out of ingredients, aside from a few sprigs of dried hellebore.

associate with

Dorothy’s Auntie Em warned her not to associate with lions and tigers and bears.

blame for, blame on

Orcs never blame themselves for ravaging the environment; instead, they blame the damage on the trolls.

capable of

Who knows what vile and abhorrent deeds trolls are capable of?

chary of

Snow White was insufficiently chary of accepting apples from strange old women.

compatible with

Is Peregrine compatible with Imogen? I doubt it!

comply with

Sybilla was reluctant to comply with the troll’s incessant importuning.

conform to (occasionally conform with)

Apprentice wizards are expected to obey their masters and conform to proper wizardly practices.

conversant with

Anyone conversant with trolls’ table manners knows better than to invite one to tea.

desire for

Even Sybilla’s desire for new experiences could not tempt her to elope with the troll.

desirous of

Being desirous of a salad for dinner, Gargantua cut some heads of lettuce as large as walnut trees.

desist from

If the troll does not desist from importuning Sybilla, she’s going to sic Berenice on him.

die of

When Homer’s belching drowned out her saxophone solo, Lisa nearly died of embarrassment.

different from

In what way is Tweedledum different from Tweedledee? I thought they were exactly alike.

disagree with

Hellebore disagreed with the pygmy, causing his stomach to rumble. (The pygmy had borborygmi.)

disdain for

The immaculate elves were too polite to show their disdain for the unkempt orcs.

enamored of

The troll is enamored of Sybilla, who in turn is enamored of Benedick.

indulge in

Berenice indulges in the curious hobby of tossing trolls.

inferior to

The orcs’ perfunctory grooming was inferior to the elves’ more meticulous toilette.

oblivious to

Imogen is oblivious to Peregrine’s flaws and all too aware of his perfection.

partial to

The walrus is extremely partial to oysters; he likes them too much for their own good.

peculiar to

A total aversion to sunlight is a condition peculiar to vampires and trolls.

preoccupation with

The troll could not comprehend Sybilla’s preoccupation with Benedick.

prevent from

There is nothing we can do to prevent Berenice from bouncing the troll off the balustrade. We’ll have to catch him on the rebound.

prior to

Prior to eating the oysters, the walrus and the carpenter took them for a stroll.

prone to

Imogen is prone to infatuations. Just ask Peregrine.

separate from

No wicked witch could separate Dorothy from her little dog Toto.

tamper with

Do not tamper with the purple potion.

weary of

Will Berenice ever weary of bouncing the troll off the balustrade?

willing to

I’m willing to bet that she won’t.

THE VAGARIES OF VERBS

Verbs are the shape-shifters of the English language. They change their forms to indicate person (who is acting), number (how many are acting), tense (when the action is happening), voice (whether something is acting, as in being active, or is being acted upon, or passive), and mood.

Mood is the best. What’s your mood? Do you feel like ordering someone around?

“Lurk!” you command. That’s the imperative mood.

“Please lurk,” you request. The mood’s still imperative, but polite.

Then there’s the indicative mood. If you’re making a simple statement, indicating or pointing out something, or asking a straightforward question, you’re using the indicative mood.

“The troll is lurking in the bushes.”

“What do you think he wants?”

Finally, there’s the subjunctive mood. You use the subjunctive when things are a bit iffy:

(statement contrary to fact)

“If I were the troll, I would head for the hills now.” (Why should the troll head for the hills? Berenice is about to pounce.)

(recommendation)

“When I find the troll, I will suggest that he hide.”

Some verbs are regular: when they shift into the past tense, they do it in the standard way by adding -ed or -d.

The troll lurked.

Berenice pounced.

Others, however, are irregular: when they form the past tense, they either change in unusual ways (think becomes thought), or they don’t change at all (put stays the same).

Here is a list of irregular verbs, showing the correct forms for the present tense, past tense, and past participle. Many you know already, but some will be unfamiliar to you. Don’t let their shifts in form fool you when you run into them on the SAT.

Irregular Verbs

|

Present Tense |

Past Tense |

Past Participle |

|

|

||

|

arise |

arose |

arisen |

|

awake |

awaked, awoke |

awaked, awoke |

|

bear |

bore |

borne |

|

beat |

beat |

beaten |

|

befall |

befell |

befallen |

|

begin |

began |

begun |

|

bend |

bent |

bent |

|

bid (command) |

bade |

bidden |

|

bid (command) |

bid |

bid |

|

bind |

bound |

bound |

|

blow |

blew |

blown |

|

break |

broke |

broken |

|

bring |

brought |

brought |

|

broadcast |

broadcast, broadcasted |

broadcast, broadcasted |

|

build |

built |

built |

|

burst |

burst |

bust |

|

buy |

bought |

bought |

|

cast |

cast |

cast |

|

catch |

caught |

caught |

|

choose |

chose |

chosen |

|

cling |

clung |

clung |

|

come |

came |

come |

|

creep |

crept |

crept |

|

deal |

dealt |

dealt |

|

dive |

dived, dove |

dived |

|

do |

did |

done |

|

draw |

drew |

drawn |

|

drink |

drank |

drunk |

|

drive |

drove |

driven |

|

eat |

ate |

eaten |

|

fall |

fell |

fallen |

|

feed |

fed |

fed |

|

feel |

felt |

felt |

|

fight |

fought |

fought |

|

find |

found |

found |

|

flee |

fled |

fled |

|

fling |

flung |

flung |

|

fly |

flew |

flown |

|

forebear |

forbore |

forborne |

|

forbid |

forbade |

forbidden |

|

forget |

forgot |

forgotten, forgot |

|

forgive |

forgave |

forgiven |

|

forsake |

forsook |

forsaken |

|

freeze |

froze |

frozen |

|

get |

got |

got, gotten |

|

give |

gave |

given |

|

go |

went |

gone |

|

grow |

grew |

grown |

|

hang* |

hung, hanged* |

hung, hanged* |

|

have |

had |

had |

|

hit |

hit |

hit |

|

hold |

held |

held |

|

kneel |

knelt, kneeled |

knelt |

|

know |

knew |

known |

|

lay |

laid |

laid |

|

lead |

led |

led |

|

leave |

left |

left |

|

lend |

lent |

lent |

|

lie |

lay |

lain |

|

lose |

lost |

lost |

|

make |

made |

made |

|

meet |

met |

met |

|

put |

put |

put |

|

read |

read |

read |

|

ring |

rang |

rung |

|

rise |

rose |

risen |

|

run |

ran |

run |

|

see |

saw |

seen |

|

seek |

sought |

sought |

|

sell |

sold |

sold |

|

send |

sent |

sent |

|

set |

set |

set |

|

shine |

shone |

shone |

|

shrink |

shrank, shrunk |

shrunk, shrunken |

|

sing |

sang |

sung |

|

sink |

sank |

sunk |

|

slay |

slew |

slain |

|

sit |

sat |

sat |

|

sleep |

slept |

slept |

|

slide |

slid |

slid |

|

sling |

slung |

slung |

|

slink |

slunk |

slunk |

|

speak |

spoke |

spoken |

|

spring |

sprang, sprung |

sprung |

|

steal |

stole |

stolen |

|

stick |

stuck |

stuck |

|

sting |

stung |

stung |

|

stride |

strode |

stridden |

|

strike |

struck |

struck |

|

swear |

swore |

sworn |

|

sweat |

sweat, sweated |

sweated |

|

sweep |

swept |

swept |

|

swim |

swam |

swum |

|

swing |

swung |

swung |

|

take |

took |

taken |

|

teach |

taught |

taught |

|

tear |

tore |

torn |

|

telecast |

telecast, telecasted |

telecast, telecasted |

|

tell |

told |

told |

|

think |

thought |

thought |

|

thrive, thrived |

throve, thriven |

throve, thriven |

|

throw |

threw |

thrown |

|

wake |

waked, woke |

waked, woken |

|

wear |

wore |

worn |

|

weep |

wept |

wept |

|

win |

won |

won |

|

wind |

wound |

wound |

|

work |

worked, wrought |

worked, wrought |

|

wring |

wrung |

wrung |

|

write |

wrote |

written |

*See the list of Words Often Misused or Confused.