Classic Human Anatomy in Motion: The Artist's Guide to the Dynamics of Figure Drawing (2015)

Chapter 7

Muscles of the Leg and Foot

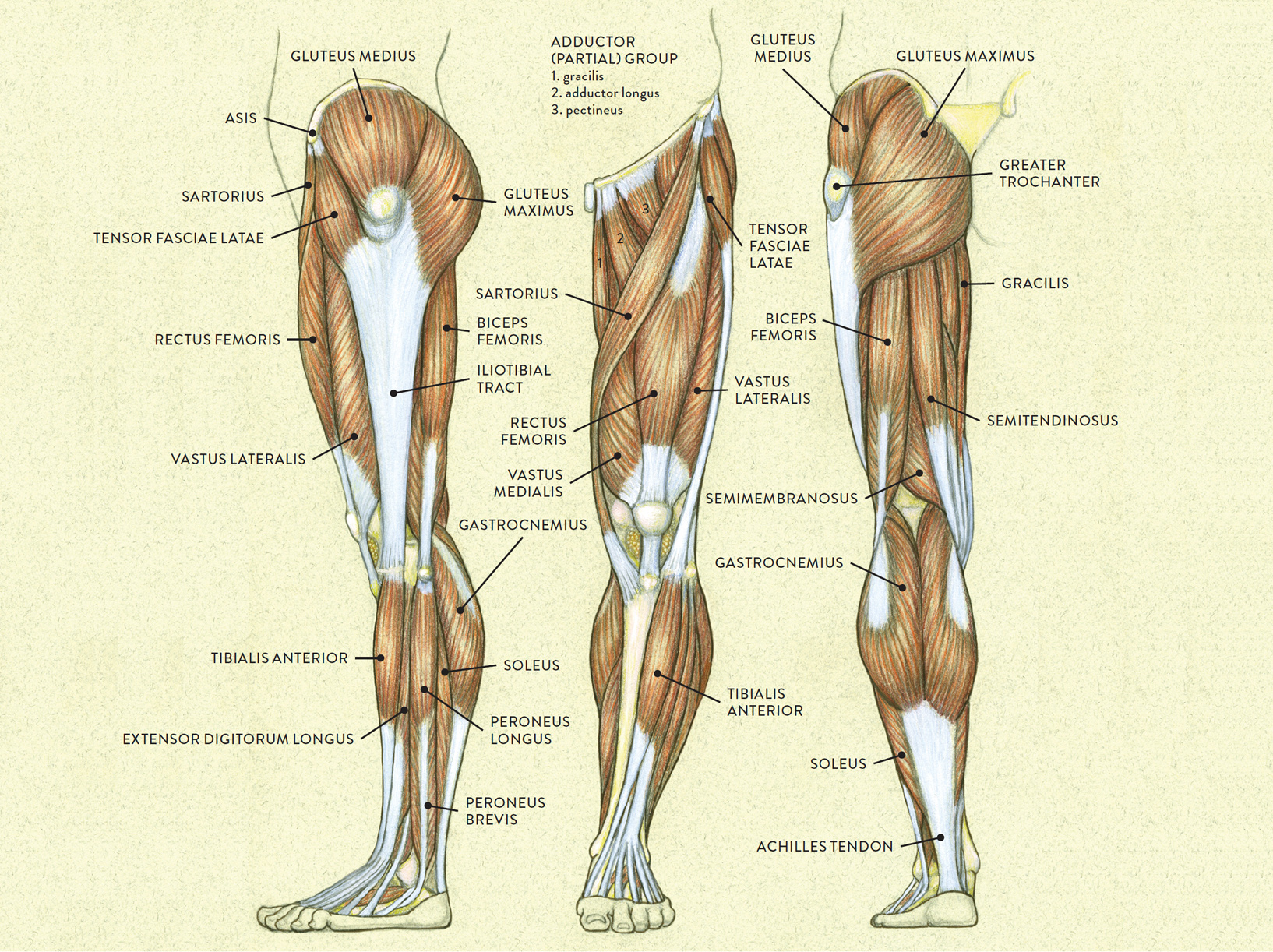

Together, the upper and lower legs and the feet make up half the length of the human figure. Legs come in all shapes and sizes, ranging from portly and stout, to the streamlined, almost emaciated legs of runway models, to the muscular legs of athletes.

Artists usually begin their study of the legs by focusing on the athletic type, because the shapes of the muscles are more easily seen. But most people’s legs are simple cylindrical forms with only a few distinct muscular shapes, such as the calf and quadriceps muscles. When depicting legs of this type, the emphasis can be placed on the rhythmic transition of forms throughout the leg. The drawings here provide a visual survey of the leg muscles.

MUSCLES OF THE UPPER AND LOWER LEG

LEFT: Lateral view

CENTER: Anterior view

RIGHT: Posterior view

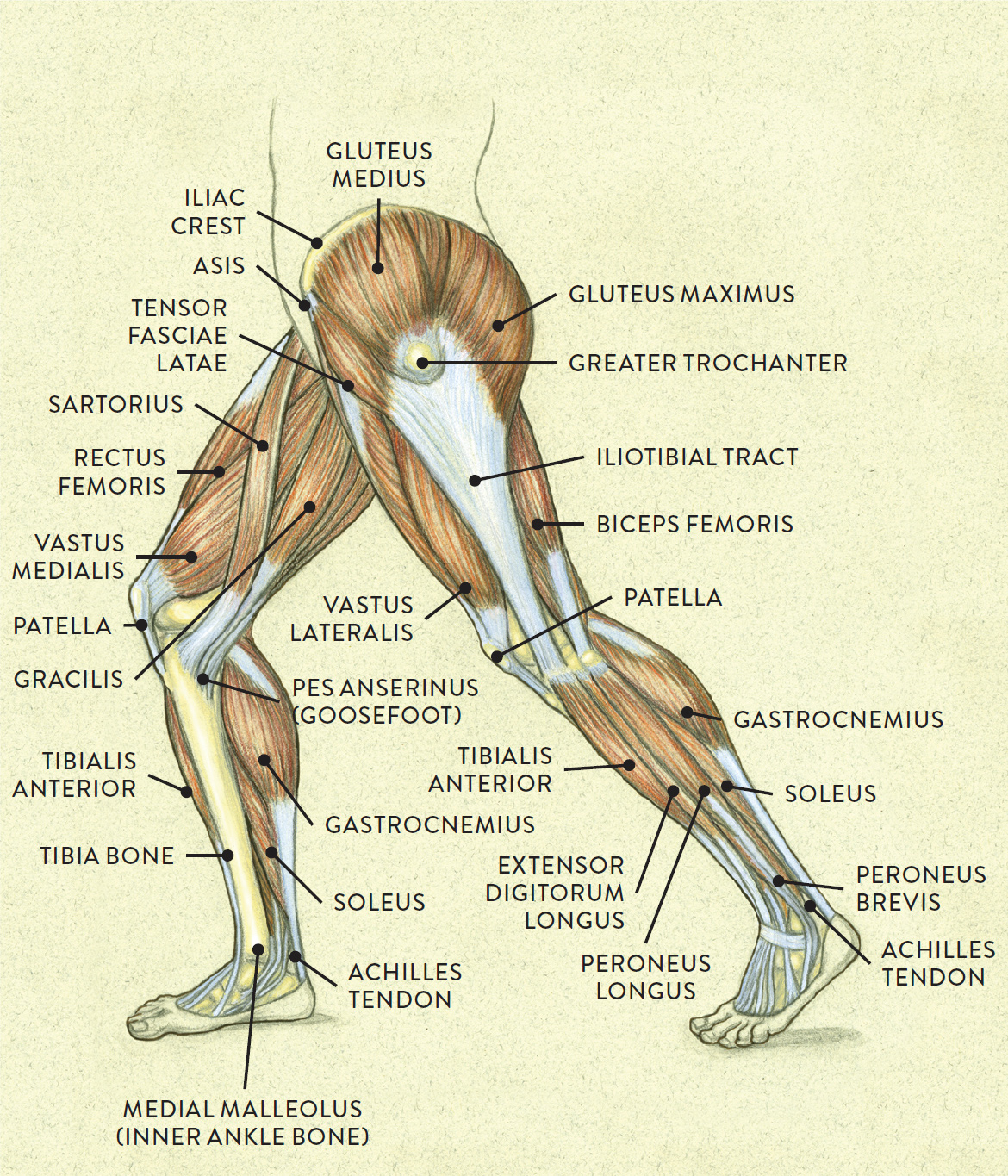

MUSCLES OF THE UPPER AND LOWER LEG

Lateral view of a pair of legs

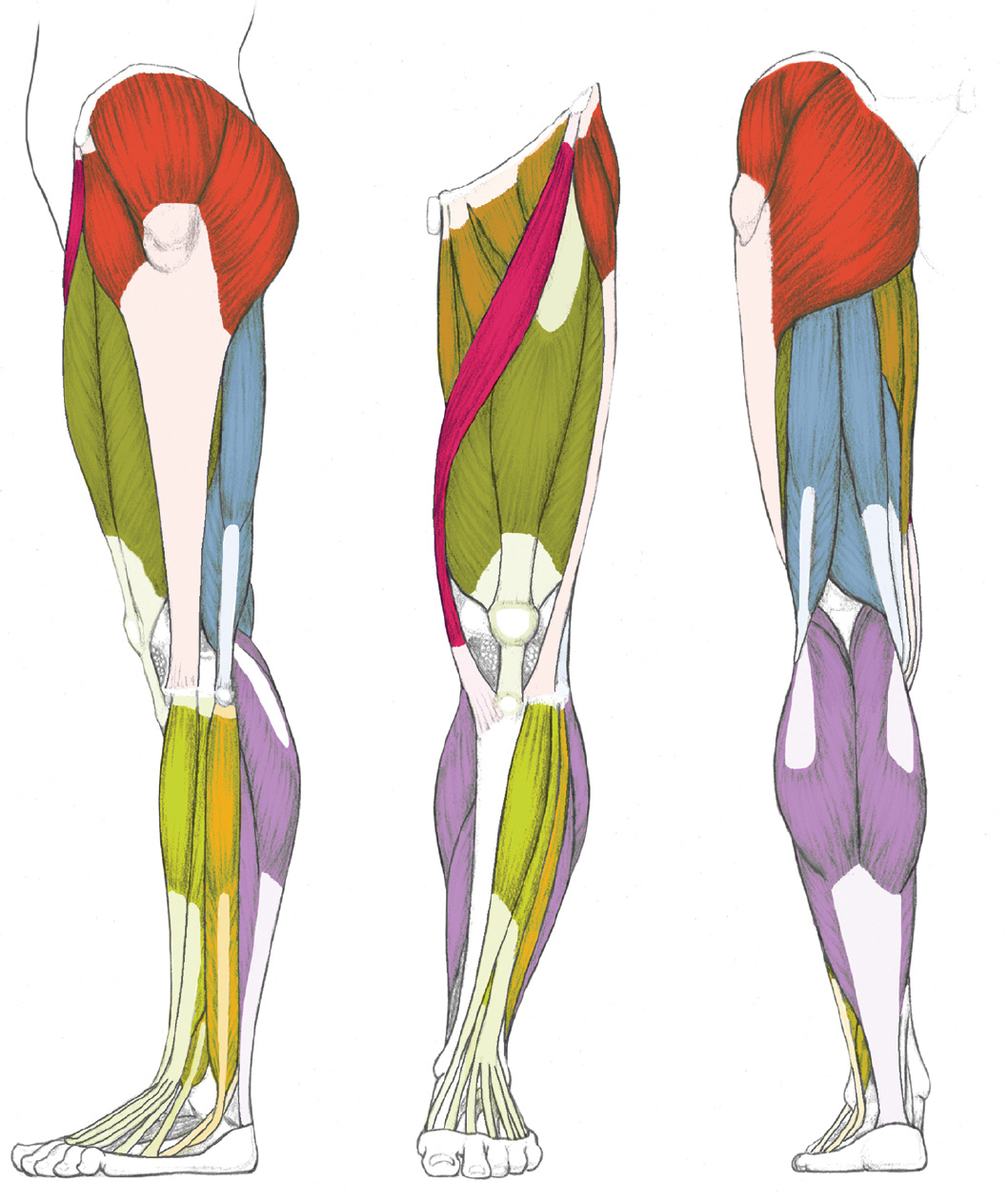

As with muscles of other regions of the body, the various muscles of the upper and lower leg can be divided into groups. The muscle groups of the upper leg region are the gluteal group, the quadriceps group, the adductor group, and the hamstring group. Those of the lower leg are the flexor group, the extensor group, and the peroneal group.

MUSCLE GROUPS OF THE UPPER AND LOWER LEG

LEFT: Lateral view

CENTER: Anterior view

RIGHT: Posterior view

GLUTEAL GROUP

QUADRICEPS GROUP

ADDUCTOR GROUP

HAMSTRING GROUP

SARTORIUS

EXTENSOR GROUP

PERONEAL GROUP

FLEXOR GROUP

Names of Leg and Foot Muscles

The names of leg and foot muscles provide clues to their location, function, shape, or size.

· Anterior means “of the front.”

· Intermedius means “in between.”

· Lateralis pertains to the outer (lateral) side of a body part.

· Medialis pertains to the median (as opposed to lateral) plane of a body part.

· Medius means “middle” or “in the middle.”

· Digiti and digitorum pertain to the toes (digits).

· Femoris pertains to the femur bone.

· Hallucis pertains to the great toe.

· Peroneus pertains to the fibula bone.

· Tibialis pertains to the tibia bone.

· Adductor pertains to moving a body part toward midline.

· Extensor pertains to stretching.

· Flexor pertains to bending.

· Rectus means “straight.”

· Brevis means “short.”

· Longus means “long.”

· Maximus means “greatest” or “largest.”

· Minimus means “smallest.”

· Vastus means “of great extent.”

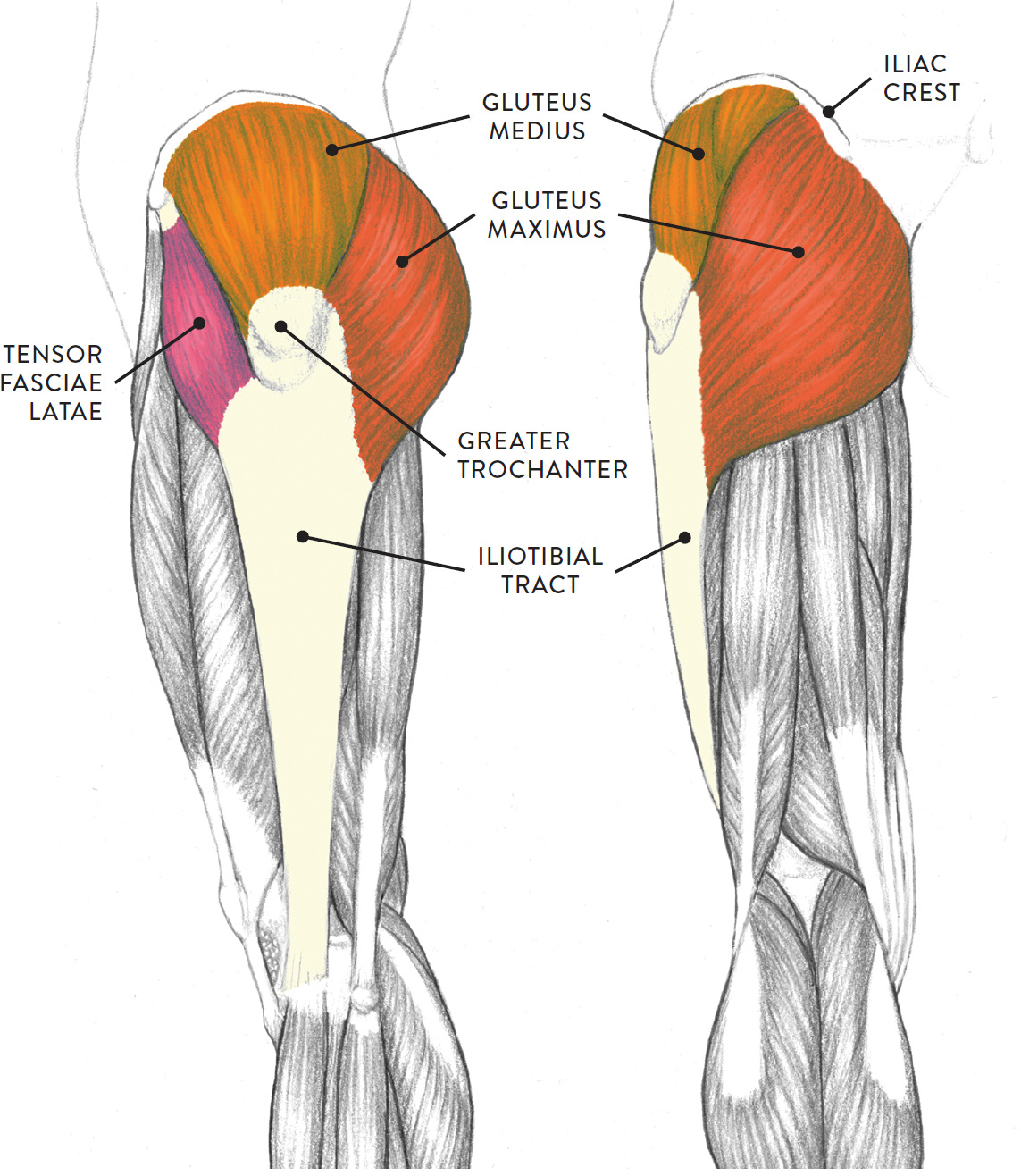

The Gluteal Muscle Group

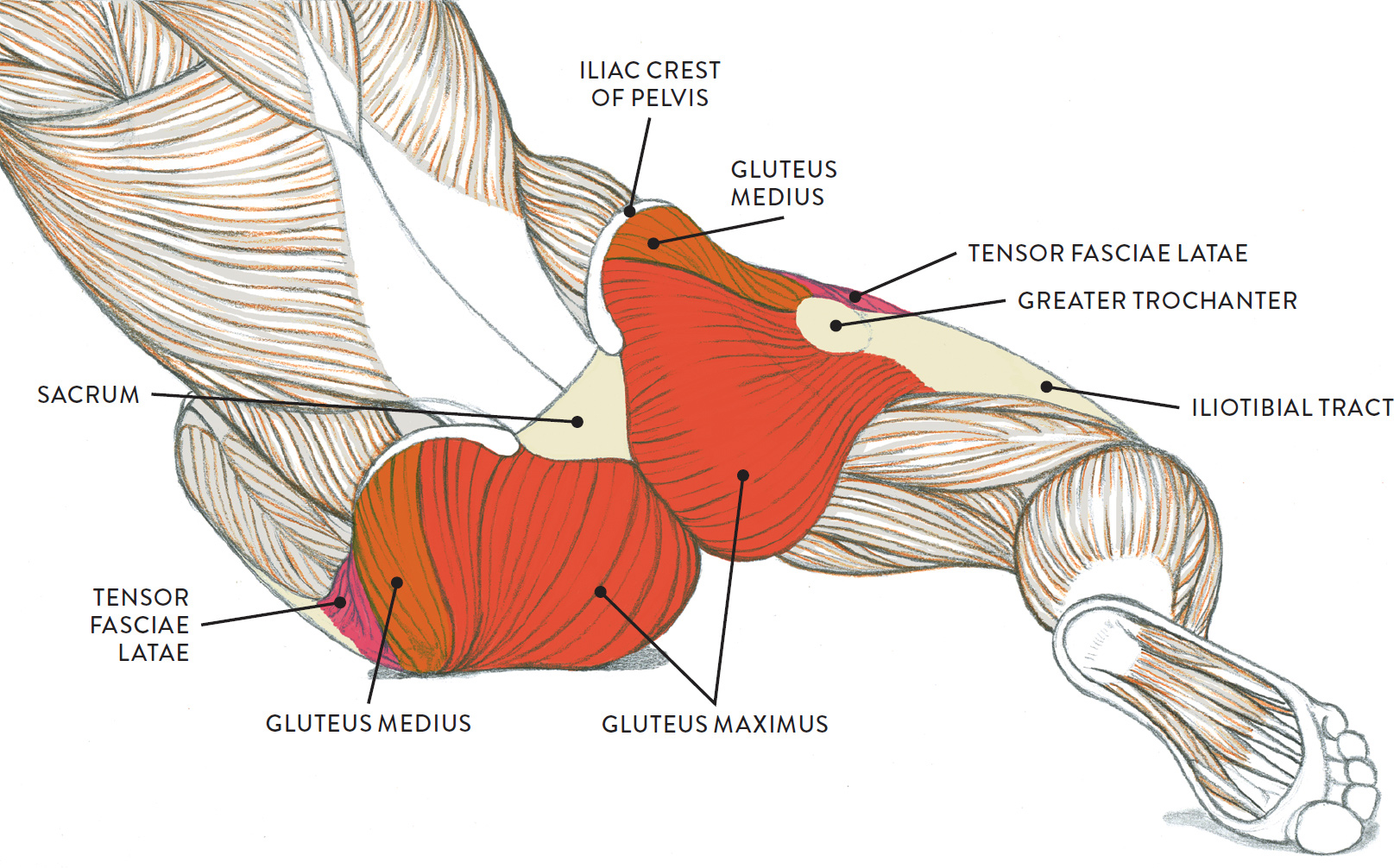

Let’s begin with a group of muscles that is part of both the torso and the legs: the gluteal (pron., GLOO-tee-ul) muscle group, shown in the following drawing. This group, occupying the lateral and posterior regions of the upper leg, primarily consists of four muscles that attach on the outer portion of the pelvis: the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae. The gluteus minimus is not seen on the surface form because it is beneath the gluteus medius, but the other three muscles do appear as three separate shapes on muscularly developed legs. If there is a predominant layer of fatty tissue in this region, however, the gluteal group is seen as a single large mass. The gluteal group moves the upper leg (femur) at the hip joint.

GLUTEAL MUSCLE GROUP

Left leg, lateral (left) and posterior (right) views

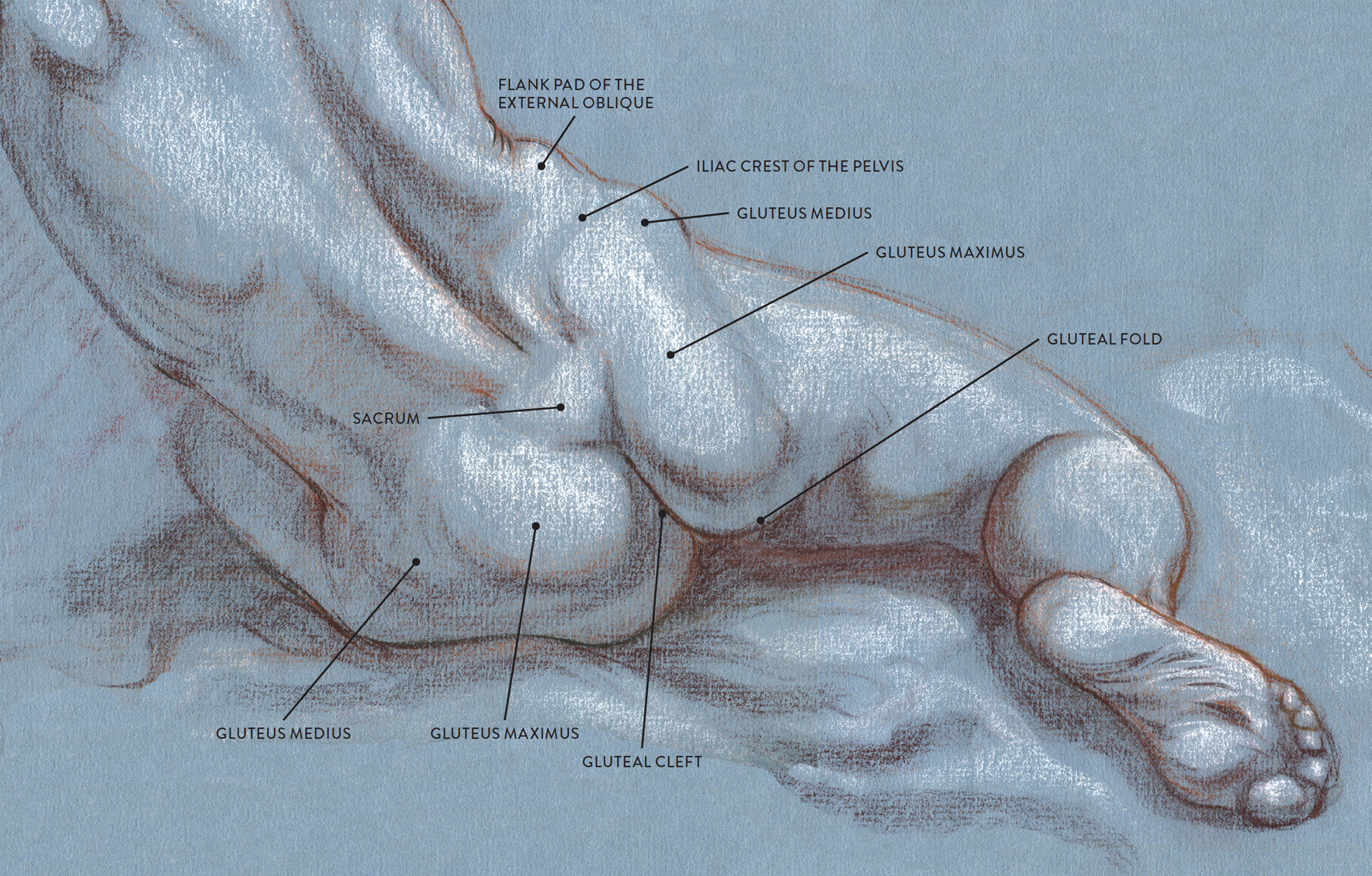

The following life study Male Figure Sitting on the Floor, shows a male figure whose hip muscles are well defined. The sacrum bone and the iliac crest of the pelvis—bony structures to which the muscles attach—are clearly seen. The accompanying muscle diagram reveals the positions of the muscles in this pose.

MALE FIGURE SITTING ON THE FLOOR

Sanguine and brown pastel pencils, white chalk on tone paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

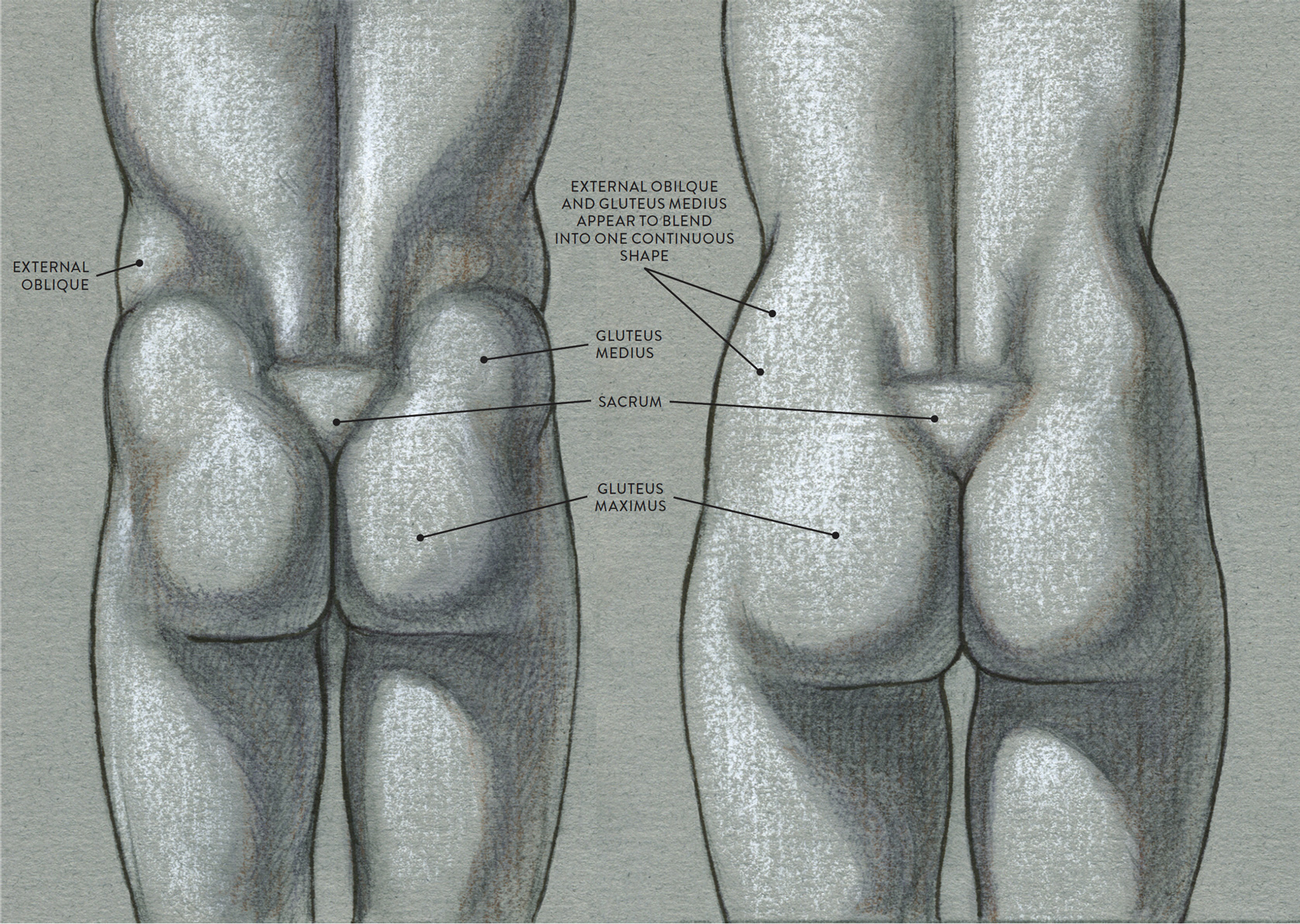

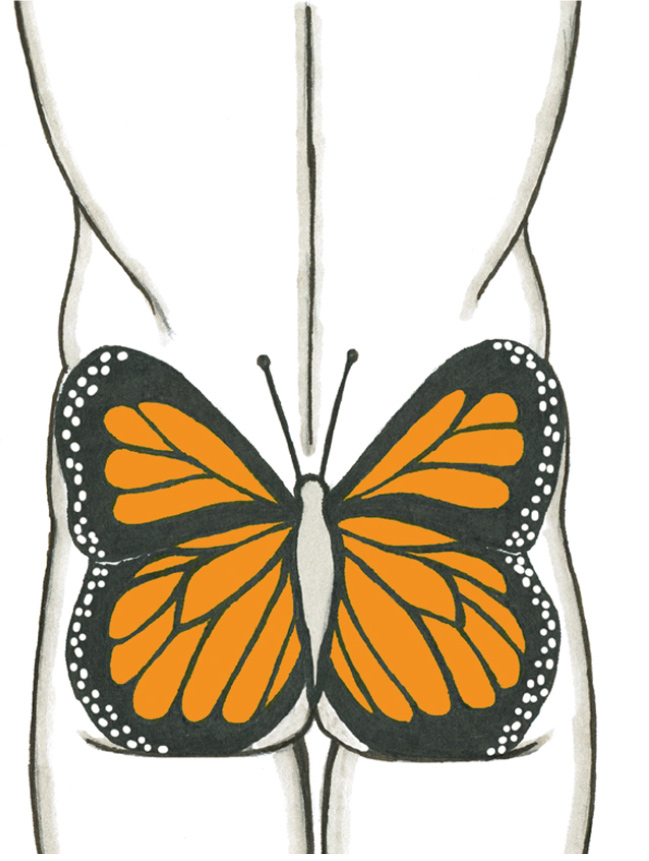

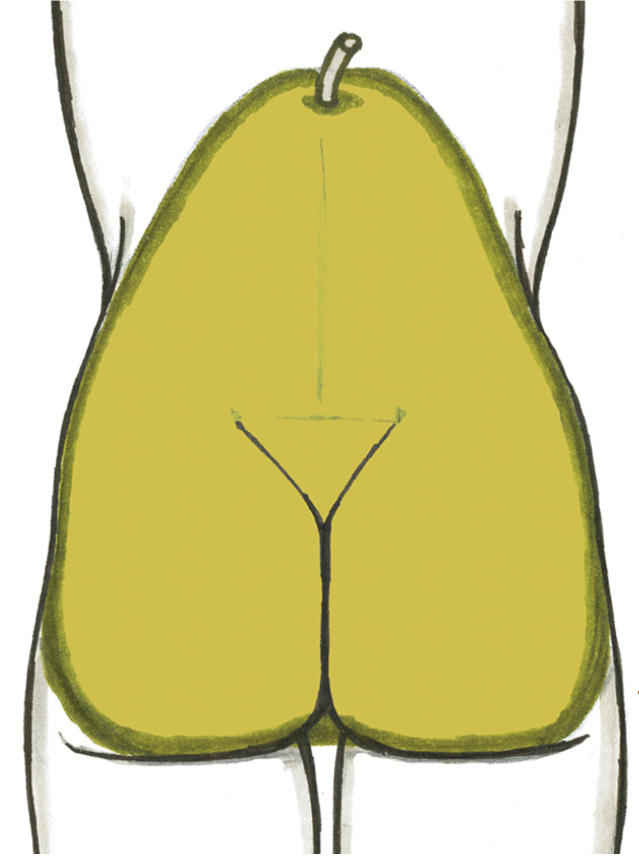

The sacrum bone is almost always noticeable, no matter what the body type, because it is not covered with muscles or substantial fatty tissue. It therefore serves the artist as a dependable visual landmark for the location of muscular forms. When viewed from the back, the shapes of the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius muscles are apparent on muscularly defined torsos, creating a butterfly shape. In torsos with a significant layer of fatty tissue, the gluteal muscles are softened into a single shape resembling a pear. In general, these shapes are characteristic of males and females, respectively, though there are many exceptions. You can use these shapes, shown in the drawings on this page, in gesture drawings, drawing them in very lightly to indicate the hips in an organic manner.

DIFFERENCES IN THE GLUTEAL MUSCLE GROUP—MALE AND FEMALE

LEFT: Male torso, posterior view

Muscle shapes are more apparent on the surface.

RIGHT: Female torso, posterior view

Muscles are covered by a thicker layer of subcutaneous tissue, softening the surface.

Male torso, posterior view

The combined forms of the gluteal muscles create a butterfly shape.

Female torso, posterior view

The gluteal muscle group and other soft-tissue forms of the female pelvis region are shaped like a pear.

The gluteus maximus (pron., GLOO-tee-us MACK-sih-mus) is the largest of the four gluteal muscles and dominates the hip region, especially in the posterior view. As the two muscles (left and right) swing away from each other near the bottom angle of the sacrum bone, they create a division called the gluteal cleft. When the upper leg is straight, a horizontal skin crease called the gluteal fold is seen on the lower border of the gluteus maximus; the fold disappears when the upper leg bends forward.

The gluteus maximus begins on the iliac crest of the pelvis and the outer edges of the sacrum and coccyx (tailbone) and inserts into the femur and the upper portion of the iliotibial tract. The iliotibial tract descends vertically down the outer side of the upper leg and eventually inserts into the lateral condyle of the tibia (large bone of lower leg). The gluteus maximus is the dominant extensor of the upper leg (femur). It bends the upper leg back from the hip joint (extension), and rotates the upper leg in an outward direction (lateral rotation).

The gluteus medius (pron., GLOO-tee-us MEE-dee-us) is a fan-shaped muscle that occupies the central portion of the pelvis bone. It is positioned between the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus maximus and appears as a prominent muscular bulge, especially when the muscle is contracting. This bulge should not be confused with the bulging form of the flank pad of the external oblique muscle, which is positioned directly above it on the side view of the torso. The iliac crest of the pelvis bone acts as a border between the two forms. If, however, there is substantial fatty tissue in this region, then the gluteus medius and the flank pad of the external oblique will appear as a single soft shape.

The gluteus medius begins on the outer surface on the ilium of the pelvis and inserts into the greater trochanter of the femur. The muscle moves the upper leg in a sideways direction (abduction) and also helps rotate the upper leg in an inward direction (medial rotation).

The gluteus minimus (pron., GLOO-tee-us MIN-ah-mus) is positioned on the central portion of the pelvis, beneath the gluteus medius. Even though this muscle is obscured from view by the gluteus medius, its fibers contribute to the bulging shape of the surface form in the side region of the pelvis. The muscle begins on the lower outer portion of the ilium and inserts on the greater trochanter of the femur. The gluteus minimus assists in the action of moving the upper leg away in a sideways direction (abduction) and helps rotate the upper leg inward (medial rotation).

The tensor fasciae latae (pron., TEN-sor FAA-shee-ee LAY-tee) is a teardrop-shaped muscle that begins on the ASIS of the pelvis and then flares slightly as it inserts into the fascia and upper portion of the iliotibial tract near the greater trochanter of the femur. Its shape is hard to detect on the surface form, although it can occasionally be seen as a small bulge in certain positions of the upper leg. When the leg is bent, or flexed, the tensor fasciae latae compresses so that the muscle fibers look as if they have a slight kink; on the surface, this compression appears as two egg-shaped forms. When the leg extends, the muscle stretches into a narrow oval. The tensor fasciae latae helps move the upper leg in a forward direction (flexion), moves the upper leg in a sideways direction (abduction), and rotates the upper leg in a inward direction (medial rotation). It also helps tense the iliotibial tract.

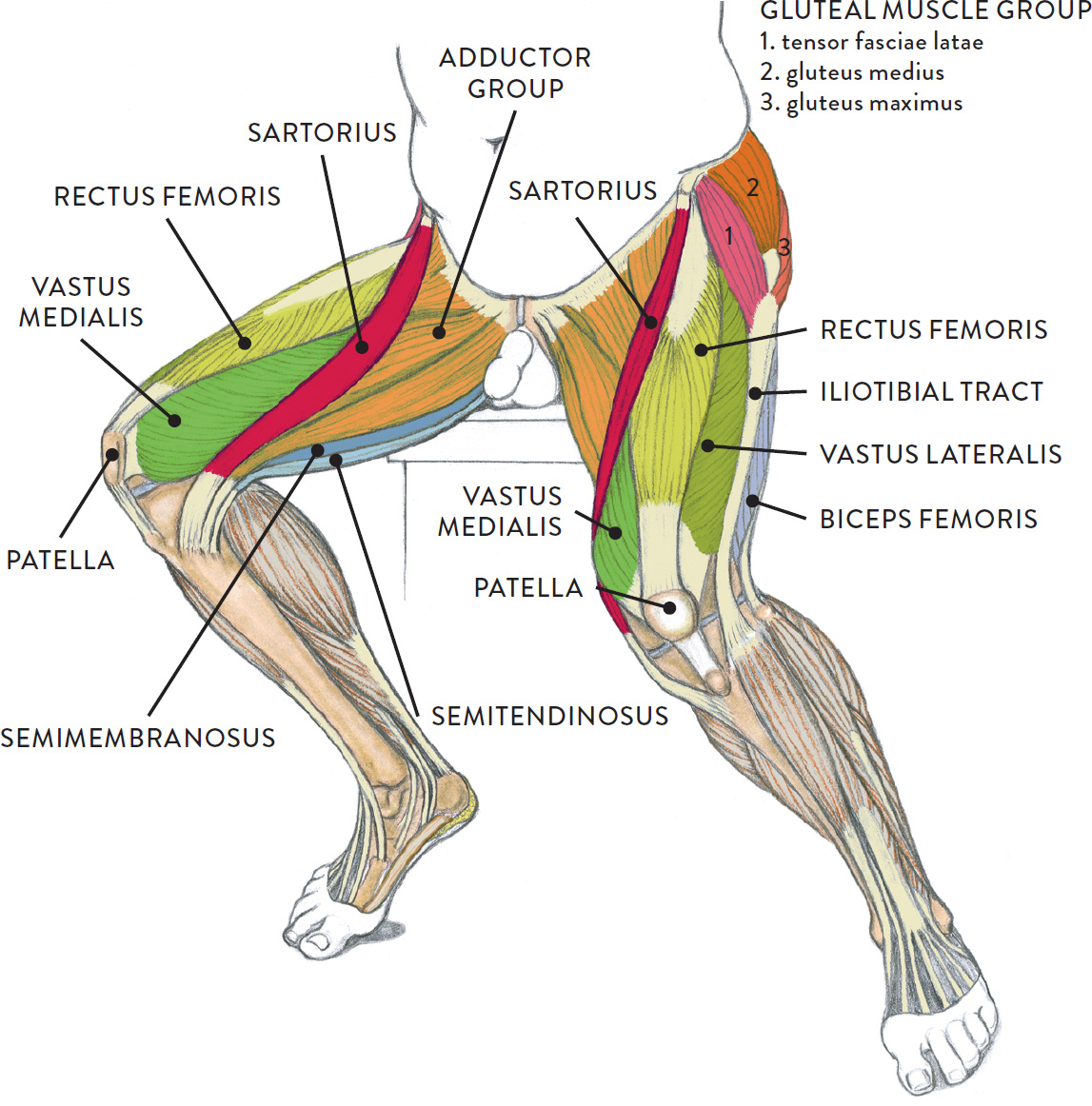

Three Muscle Groups of the Upper Leg, with the Sartorius Muscle

Besides the gluteal group (which is also part of the torso region), there are three main muscle groups of the upper leg. The most prominent group on the anterior region of the leg is the quadriceps muscle group, also known as the quadriceps femoris, quads, or extensor group of the upper leg. Located on the medial (inner) portion of the upper leg is the adductor muscle group, sometimes referred to as the inner thigh muscles. Occupying the posterior region of the upper leg is the hamstring muscle group, also called the flexor group of the upper leg. An elongated muscle called the sartorius, which does not belong to any group, lies between the quadriceps and adductor groups. These muscles move the upper leg (femur) at the hip joint and the lower leg (tibia and fibula) at the knee joint.

The Quadriceps Muscle Group

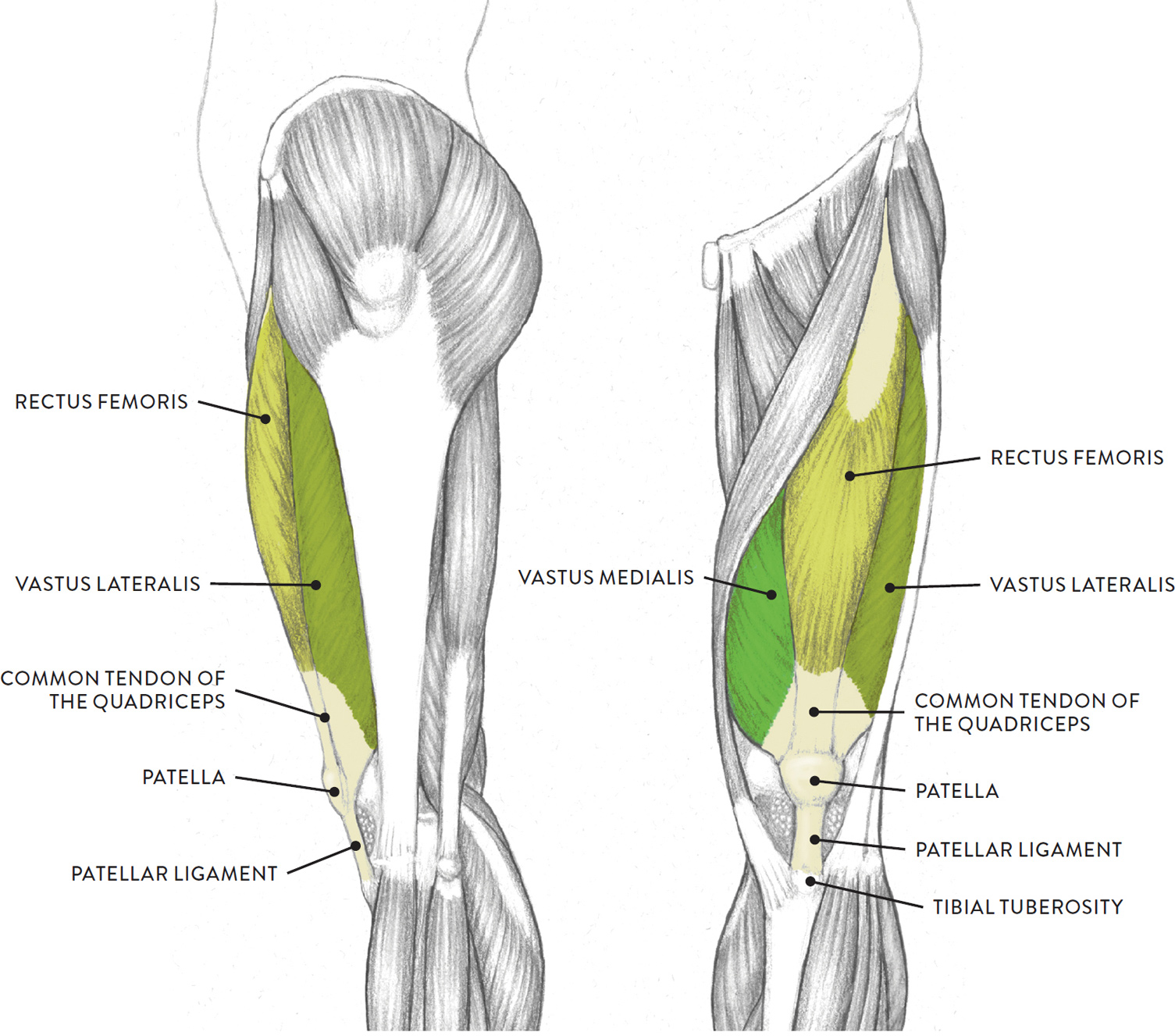

The main muscle group on the anterior region of the upper leg is the quadriceps group (pron., KWAHD-drih-seps), shown in the drawing opposite. The term quadriceps means “four-headed” (Latin: quad = four, ceps = head). Some experts consider the quadriceps to be one muscle consisting of four parts, while others define the quadriceps as a group of four individual muscles. The latter, more traditional definition is the one I follow here.

QUADRICEPS MUSCLE GROUP

Left leg, lateral (left) and anterior (right) views

Three of the muscles (vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and rectus femoris) are apparent on the surface form in muscular types, while the fourth (vastus intermedius) is always obscured from view. The borders of the quadriceps are the sartorius muscle (medial side) and the tensor fasciae latae muscle with the iliotibial tract (lateral side). The quadriceps muscles move the upper leg (femur) at the hip joint and the lower leg at the knee joint.

Each muscle of this group starts at four different locations on the femur and pelvis, and the muscles merge into one common tendon (tendon of quadriceps) that inserts into the patella (kneecap). The tendon continues past the patella to attach into the tibial tuberosity of the tibia; this latter segment of the tendon is usually called the patellar ligament. When depicting the knee region, it is essential for artists to locate the patella because it is the main anchoring site for the quadriceps muscle group.

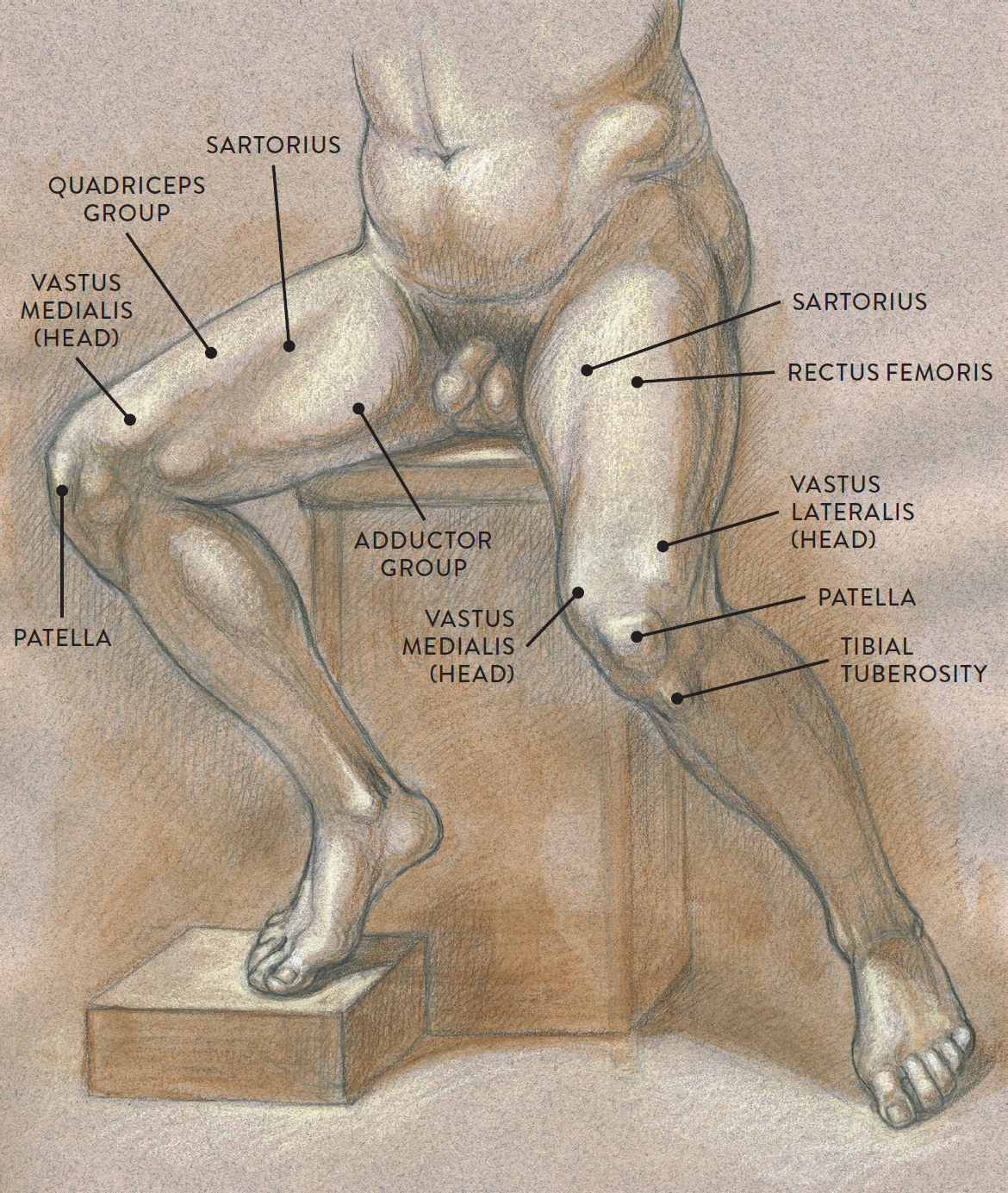

The next life study, Seated Male Figure with Robust, Muscular Legs, focuses on the muscular forms of the anterior region of the upper legs. In it, you can see the quadriceps group, the adductor group, and the sartorious muscle between them. The accompanying muscle diagram further reveals the positions of the muscles in this pose.

SEATED MALE FIGURE WITH ROBUST, MUSCULAR LEGS

Graphite pencil, watercolor wash, and cream and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The rectus femoris (pron., RECK-tus FEM-o-riss, RECK-tus FEE-mor-iss, or RECK-tus fee-MORE-iss) occupies the central portion of the quads and is positioned over the vastus intermedius. The muscle begins near the ASIS of the pelvis directly above the acetabulum (hip socket). It inserts into the patella by way of the common quadriceps tendon, which continues on to the tibial tuberosity of the tibia. The rectus femoris helps straighten the lower leg at the knee joint (extension) and also helps bend the femur in a forward direction at the hip joint (flexion).

The vastus lateralis (pron., VAS-tus laa-ter-AL-iss) produces the thick mass of muscular form on the outer part of the upper leg and also forms a prominent bulge (the outer head) near the kneecap when the quadriceps muscle contracts. The muscle begins on the posterior side of the femur, near the greater trochanter. It inserts into the patella by way of the common quadriceps tendon. The vastus lateralis straightens the lower leg at the knee joint (extension).

The vastus medialis (pron., VAS-tus mee-dee-AL-iss) is positioned on the medial portion (inner thigh) of the upper leg. When this muscle contracts, it produces a rich bulge near the kneecap, toward the inner part of the leg. The muscle begins on the posterior side of the femur, near the lesser trochanter. It inserts into the patella by way of the common quadriceps tendon. The vastus medialis helps straighten the lower leg at the knee joint (extension) and also helps stabilize the patella.

The vastus intermedius (pron., VAS-tus in-ter-ME-de-us) is positioned between the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis. This muscle is usually not seen on the surface form because the rectus femoris muscle is positioned on top, obscuring it from view. The muscle begins on the front and side portions of the femur. It inserts into the patella by way of the common quadriceps tendon. Like the other vastus muscles, the vastus intermedius helps straighten the lower leg from the knee joint (extension).

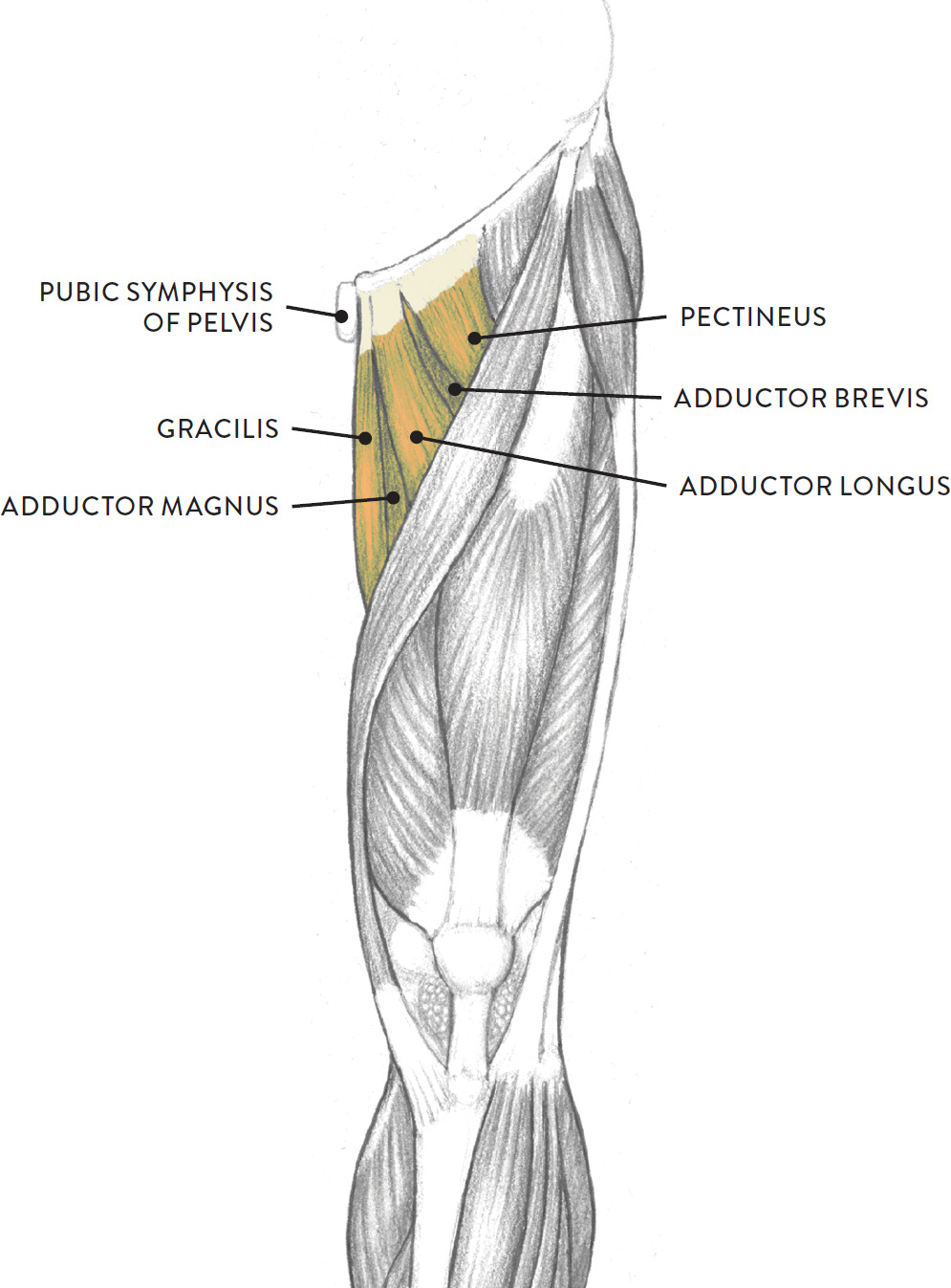

The Adductor Muscle Group

Located on the medial (inner) portion of the upper leg is a group of muscles called the adductor group, commonly known as the inner thigh muscles. The individual muscles of the adductor group are the adductor magnus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, pectineus, and gracilis, all shown in the drawing below. They contribute to the cylindrical shape of the upper leg and are not usually visible as separate muscles on the surface form.

|

Adductor Group Muscles Pronunciation Guide |

|

|

MUSCLE |

PRONUNCIATION |

|

adductor brevis |

ah-DUCK-tor BREH-viss |

|

adductor longus |

ah-DUCK-tor LON-gus |

|

adductor magnus |

ah-DUCK-tor MAG-nuss |

|

gracilis |

GRAH-suh-liss |

|

pectineus |

peck-TIN-ee-us |

ADDUCTOR MUSCLE GROUP

Left leg, anterior view

The individual muscles of the adductor group begin at various locations on the lower pelvis, including the ischium bone, the pubic bone, and the vicinity of the pubic symphysis. They insert along the whole back of the femur, while the gracilis muscle moves past the knee joint to attach into the tibia. As their name indicates, they mainly perform the action of moving an outstretched leg positioned sideways from the torso back to a normal standing position (adduction). Most of these muscles also help in bending the upper leg at the hip joint (flexion).

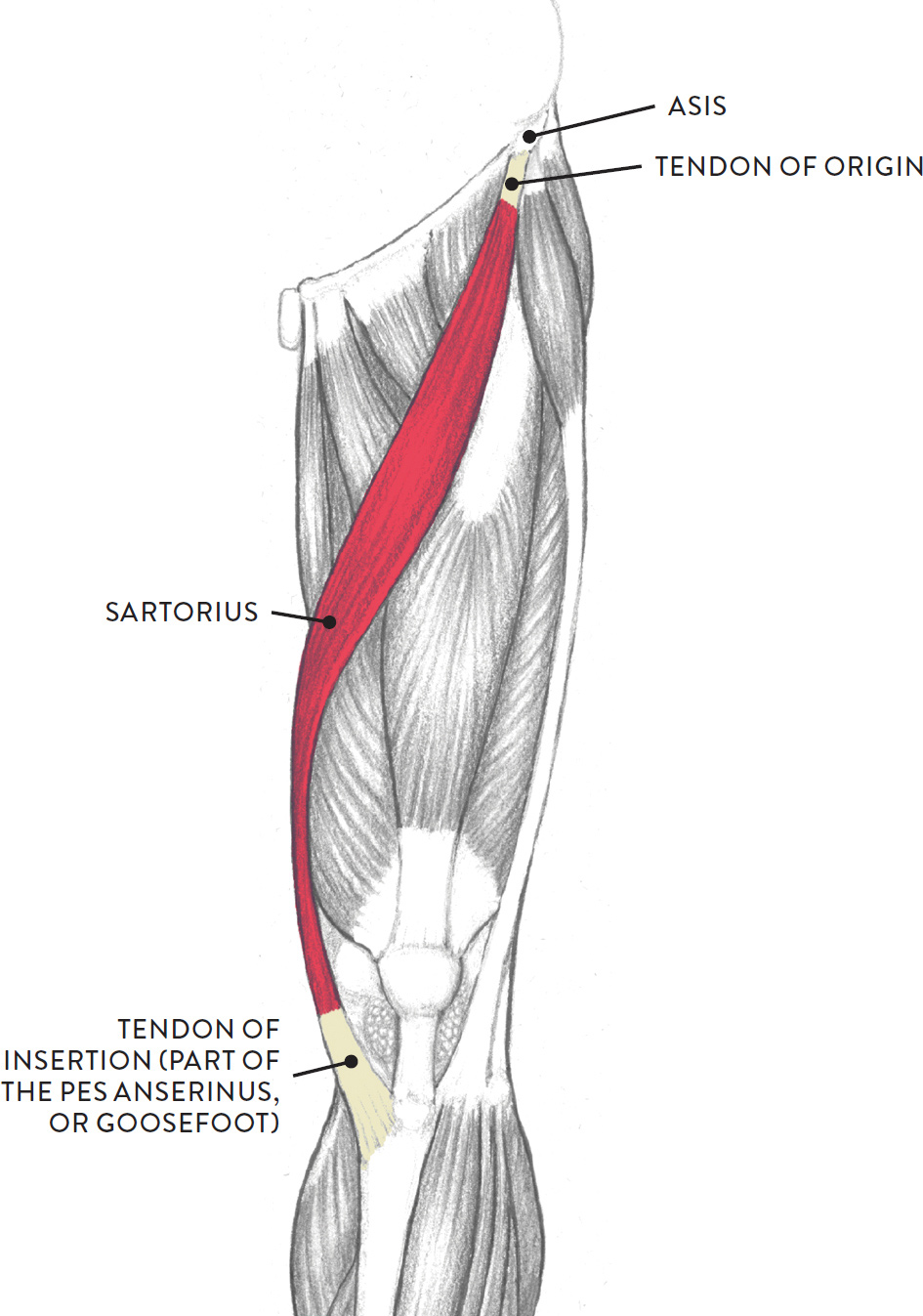

The Sartorius Muscle

The sartorius (pron., sar-TOR-ee-us), shown in the following drawing, is an elongated, straplike muscle positioned between the quadriceps and adductor muscle groups. It does not belong to any group of muscles. On athletic legs, both sides of the sartorius can usually be seen, while on average legs only the inner border of the sartorius is detectible, appearing as an elongated subtle indentation traveling diagonally on the thigh. When drawing this region, the indentation can be indicated with a soft tone or shadow.

The sartorius begins at the ASIS of the pelvis; its lower portion wraps snuggly around the inner condyles of both the femur and tibia and inserts into the medial condyle of the tibia. The tendon of the sartorius, along with other tendons, forms what is called the pes anserinus, meaning “goosefoot” because of its webbed appearance, resembling the foot of a goose. The serpentine rhythm of the sartorius, as it sweeps obliquely downward across the upper leg, is continued on the lower leg by the tibia, or shinbone, and this serpentine movement of both muscle and bone has been utilized by many figurative classical artists, past and present.

SARTORIUS

Left leg, anterior view

Contributing to many actions of the upper and lower leg, the sartorius helps move the upper leg in a forward direction from the hip joint (flexion), moves the upper leg in a side direction away from the midline of the body (abduction), rotates the upper leg in an outward direction (lateral flexion), and bends the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of the knee).

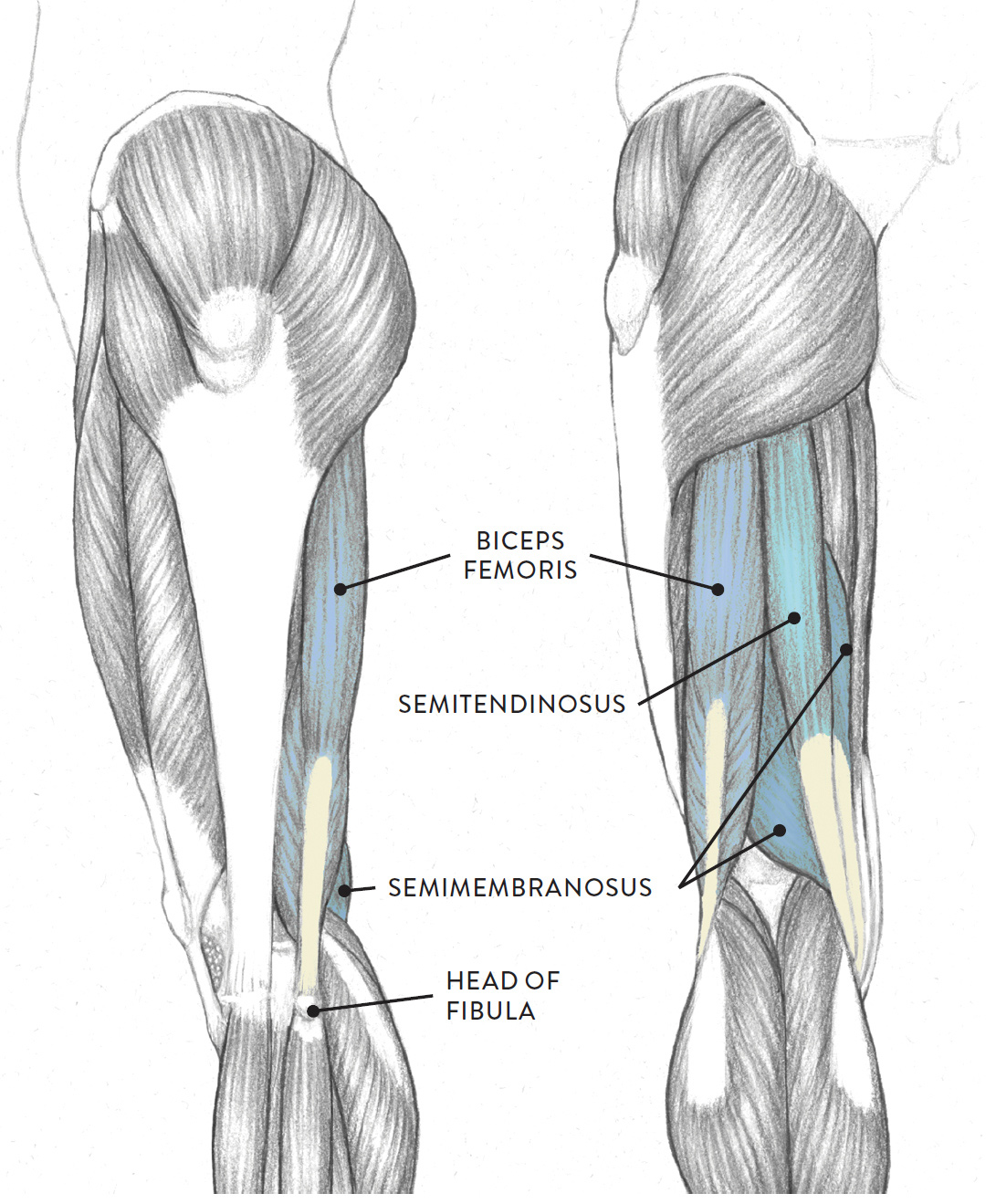

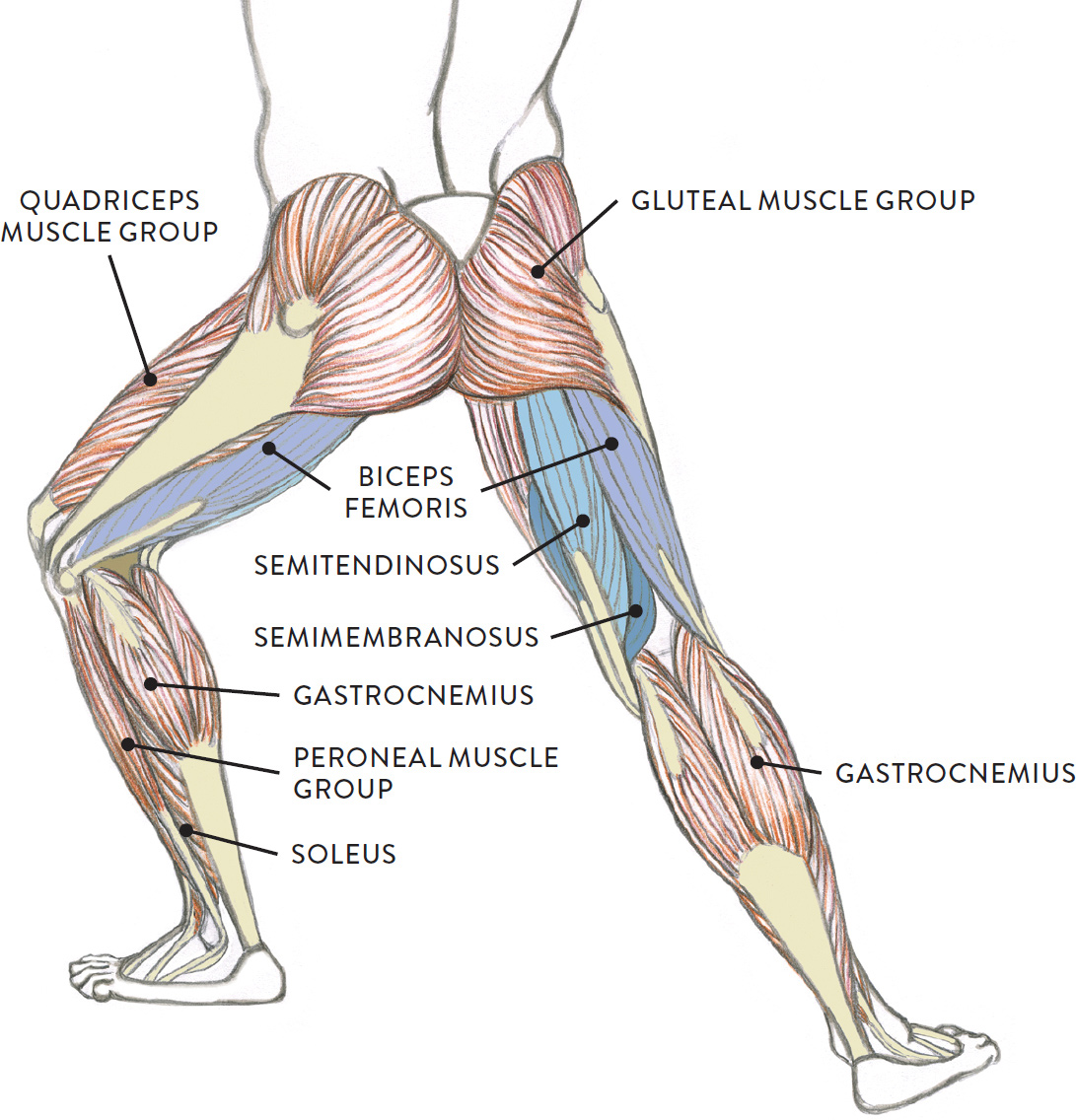

The Hamstring Muscle Group

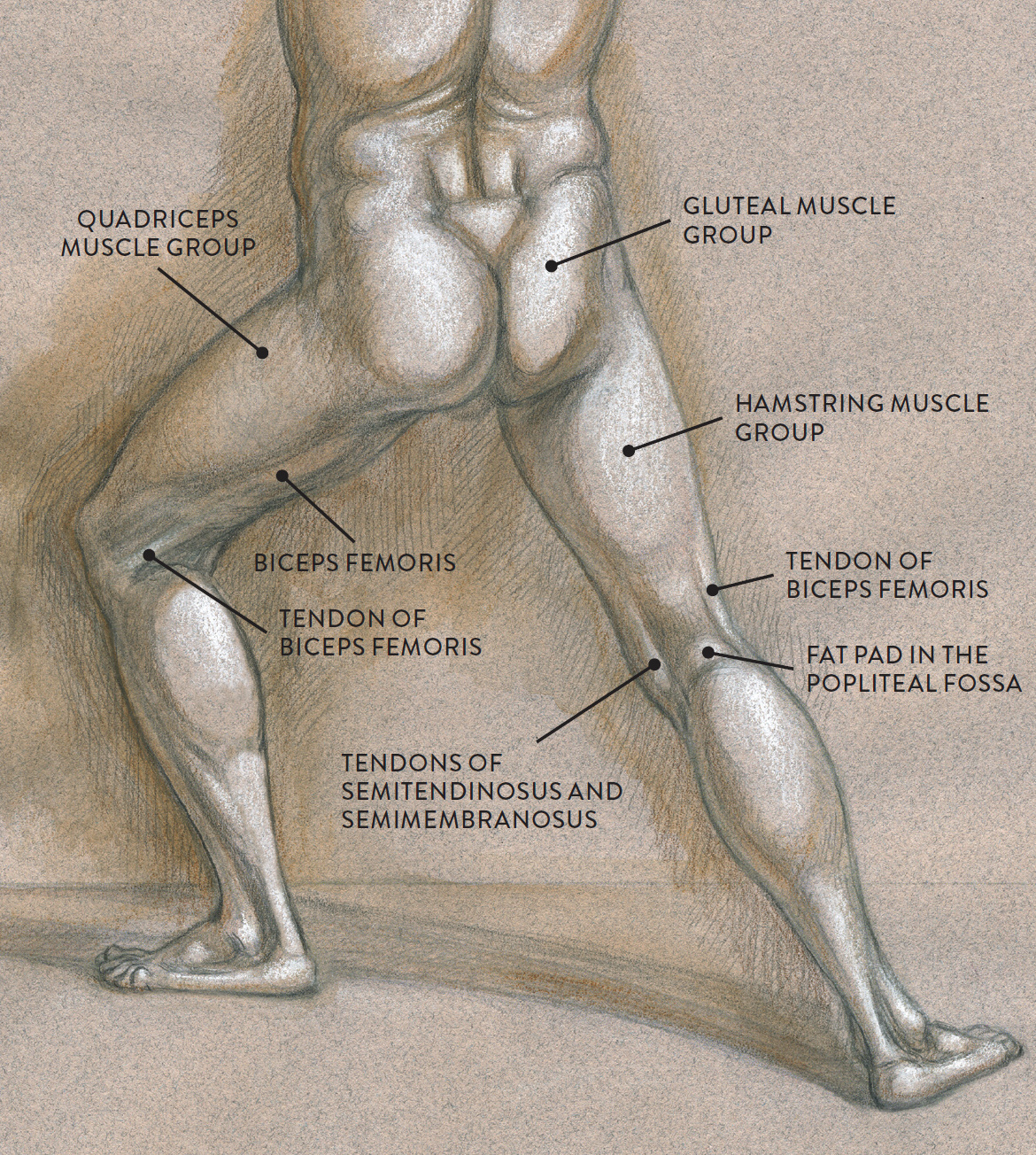

The hamstring muscle group, shown in the next drawing, consists of three muscles—the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus—that occupy most of the posterior region of the upper leg. Usually, the hamstring group appears on the surface as a cylindrical shape, with little evidence of the individual muscles. Only on athletic legs can you see a slight furrow between the biceps femoris and the semitendinosus. The tendons of the hamstring muscles, however, do appear as “tongs” grasping the upper portions of the gastrocnemius (calf) muscle. Between the tendons is a space called the popliteal fossa, with a small fat pad. The hamstring muscles are flexors, moving the upper leg (femur) at the hip joint and the lower leg (tibia and fibula) at the knee joint.

HAMSTRING MUSCLE GROUP

Left leg, lateral (left) and anterior (right) views

The following life study Male Figure in a Lunging Pose, shows a figure bending one leg while the other is outstretched. The accompanying muscle diagram further reveals where the muscles are positioned in this pose.

MALE FIGURE IN A LUNGING POSE

Graphite pencil, watercolor wash, and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The biceps femoris (pron., BI-seps FEM-or-iss) is positioned on the posterior and lateral portions of the upper leg. As its name implies, it has two heads (a long head and a short head), which usually appear as a single large form on the outer posterior region of the upper leg. The long head begins on the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis and the short head begins at the back of the femur. The powerful tendon of the biceps femoris, which produces a thick, cordlike form on the surface, inserts into the small, spherical head of the fibula. The biceps femoris bends the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of lower leg), rotates the lower leg in an outward direction when the knee is bent (lateral rotation of lower leg), and straightens the upper leg at the hip joint (extension).

The semitendinosus (pron., SEM-ee-TEN-dih-NO-sus or seh-MY-ten-din-OH-sus) is positioned on the posterior and medial portions of the upper leg. The muscle begins on the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis. Its tendon and the tendon of the semimembranosus are side by side and attach on the medial side of the tibia bone. The semitendinosus helps bend the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of the lower leg), rotates the lower leg in an inwardly direction (medial rotation, but only when the knee is bent), and helps straighten the upper leg at the hip joint (extension).

The semimembranosus (pron., SEM-ee-mem-brah-NO-sus or seh-MY-mem-bran-OH-sus) is mostly covered by the semitendinosus and is hard to detect on the surface of an average leg, although occasionally a small bulge will appear near the back of the knee region. The muscle begins on the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis and inserts on the posterior surface of the inner condyle of the tibia. The semimembranosus helps bend the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of the lower leg) and rotates the lower leg in an inward direction (medial rotation, but only when the knee is bent). It also helps straighten the upper leg at the hip joint (extension).

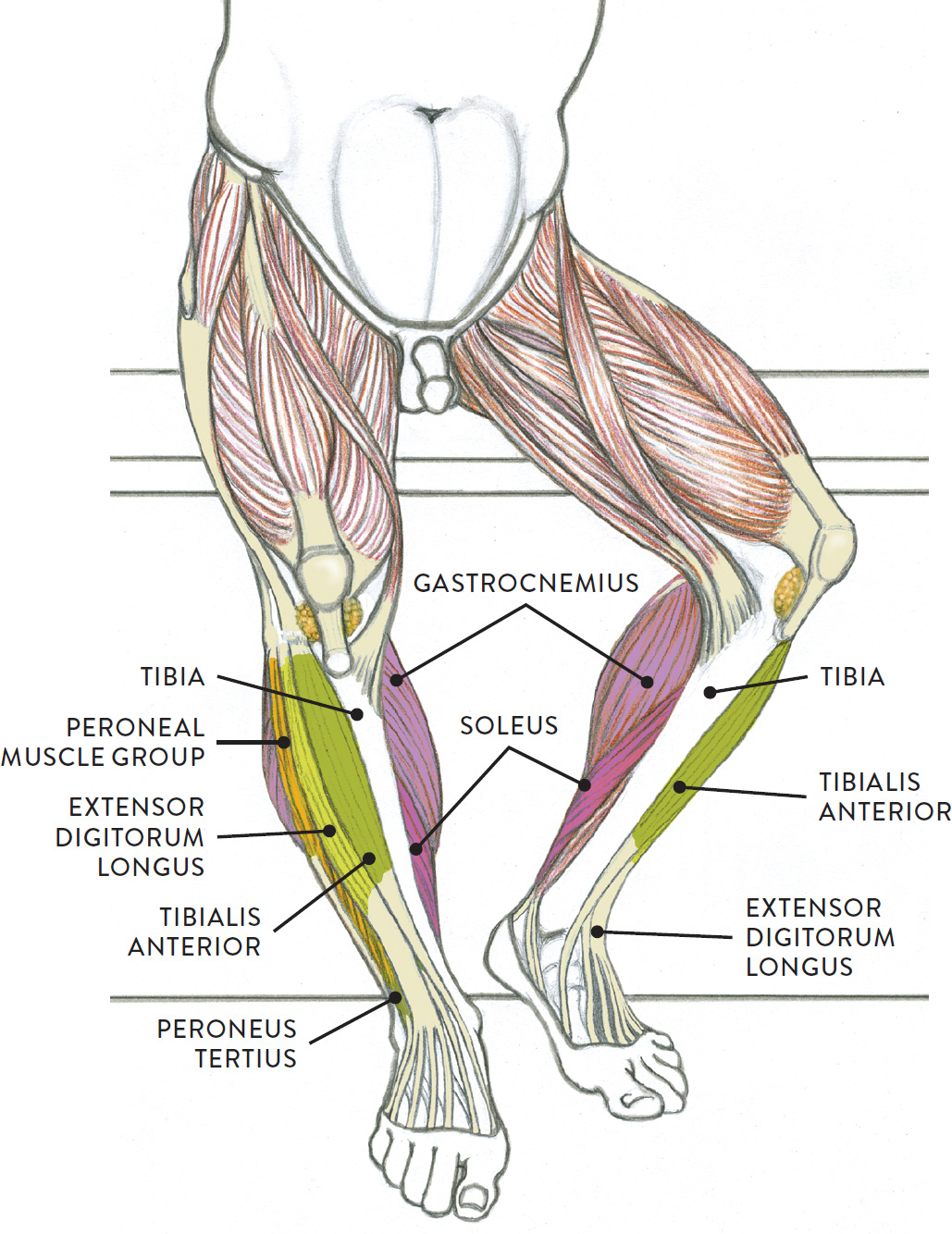

Three Muscle Groups of the Lower Leg

Muscles of the lower leg move the lower leg at the knee joint and the foot at the ankle joint. There are three main muscle groups. The most prominent is the flexor muscle group of the lower leg, commonly known as the calf muscles, located on the posterior region of the lower leg. Situated on the anterior portion of the lower leg is the extensor muscle group of the lower leg, and occupying the lateral (outer) region of the lower leg is the peroneal muscle group.

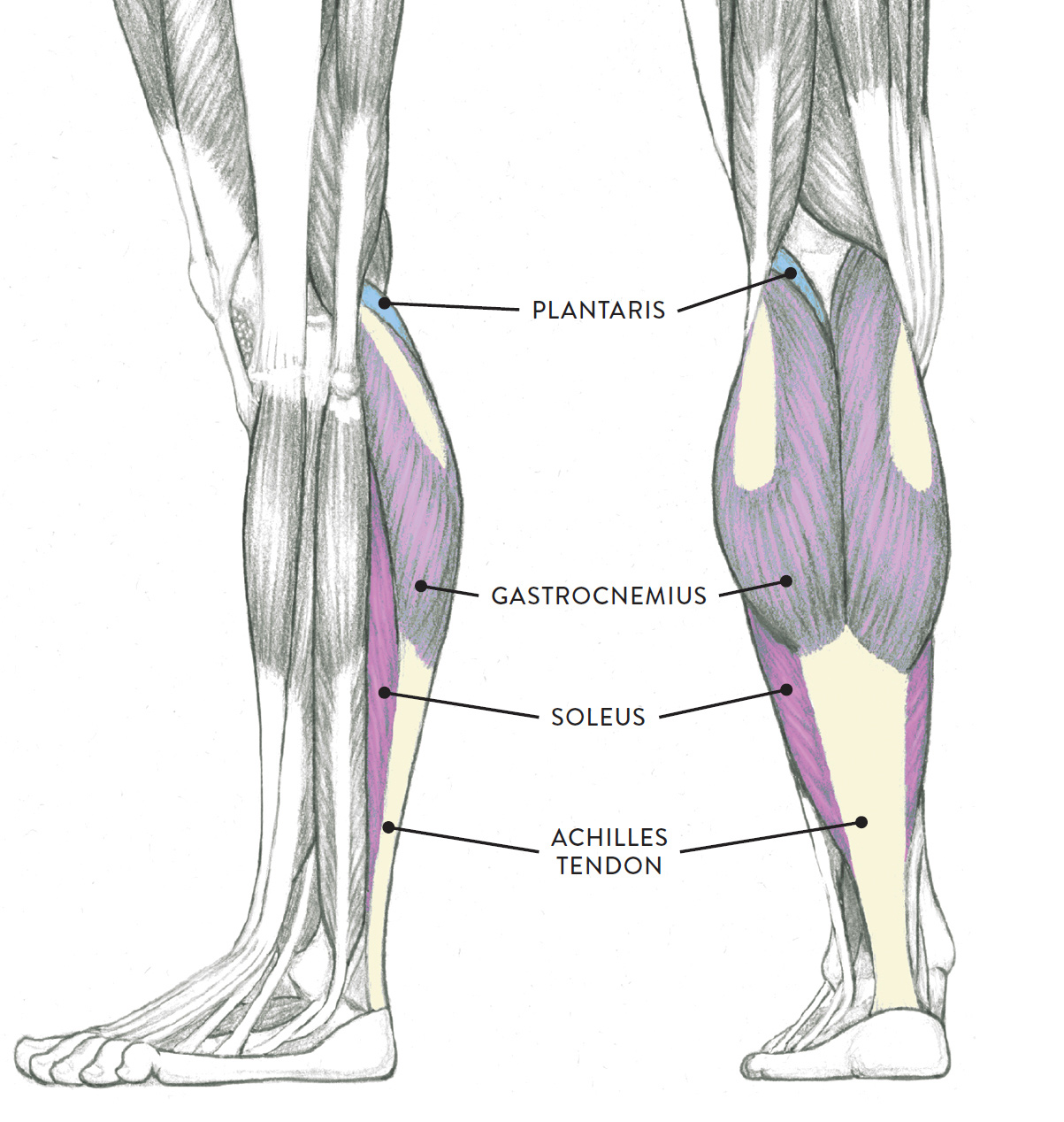

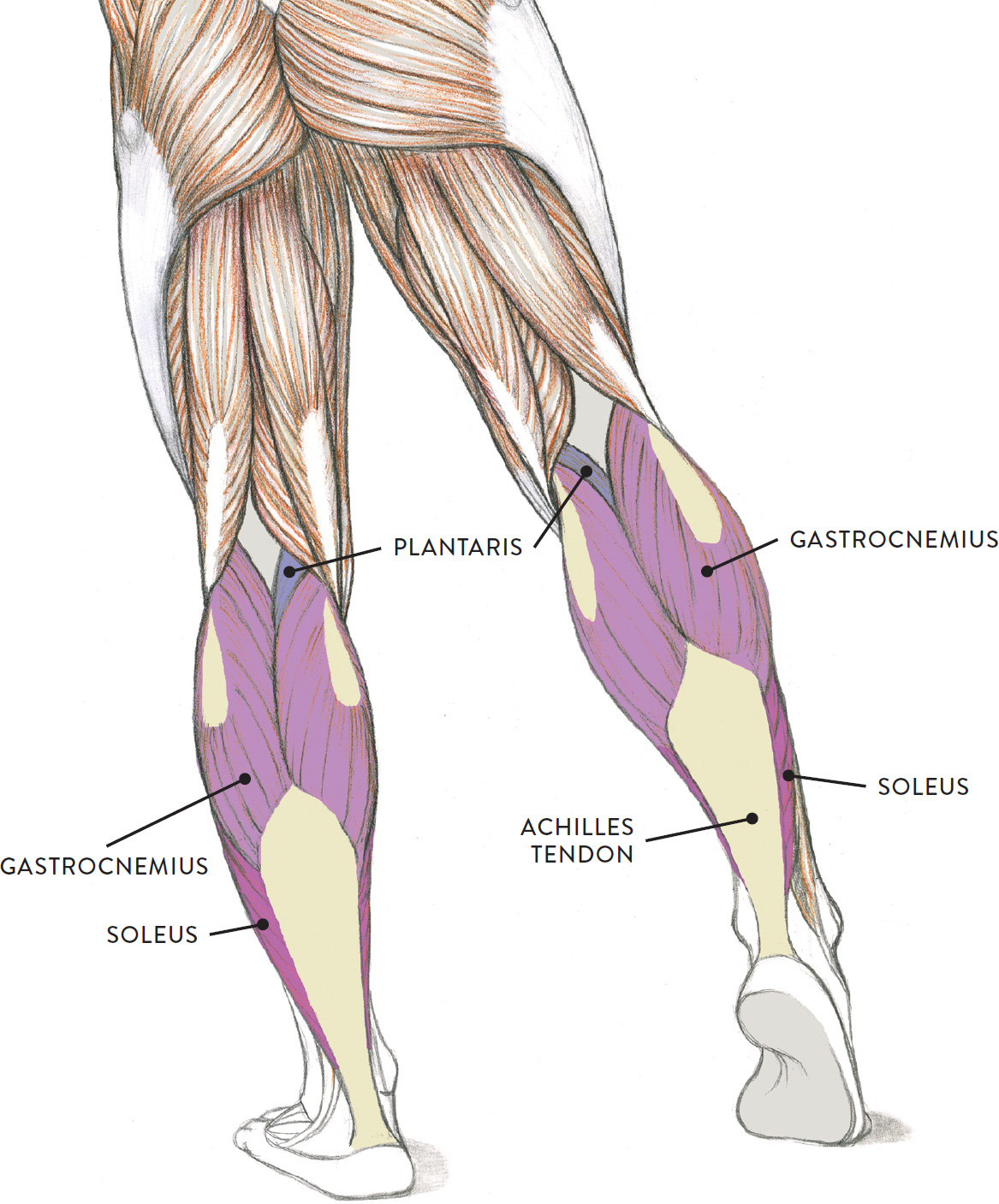

The Flexor Muscle Group of the Lower Leg

The flexor group occupies the posterior region of the lower leg, as shown in the next drawing. The group consists of the two-headed gastrocnemius muscle, the soleus muscle, and a smaller muscle called the plantaris. An older term—triceps surae (pron., TRI-seps SHUR-ay), which means “the three-headed muscle of the calf”—refers to both the gastrocnemius (with its two heads) and the soleus but not the plantaris muscle. The flexor group muscles move the lower leg (tibia) at the knee joint and the foot at the ankle joint.

FLEXOR MUSCLE GROUP OF THE LOWER LEG

Left leg, lateral (left) and posterior (right) views

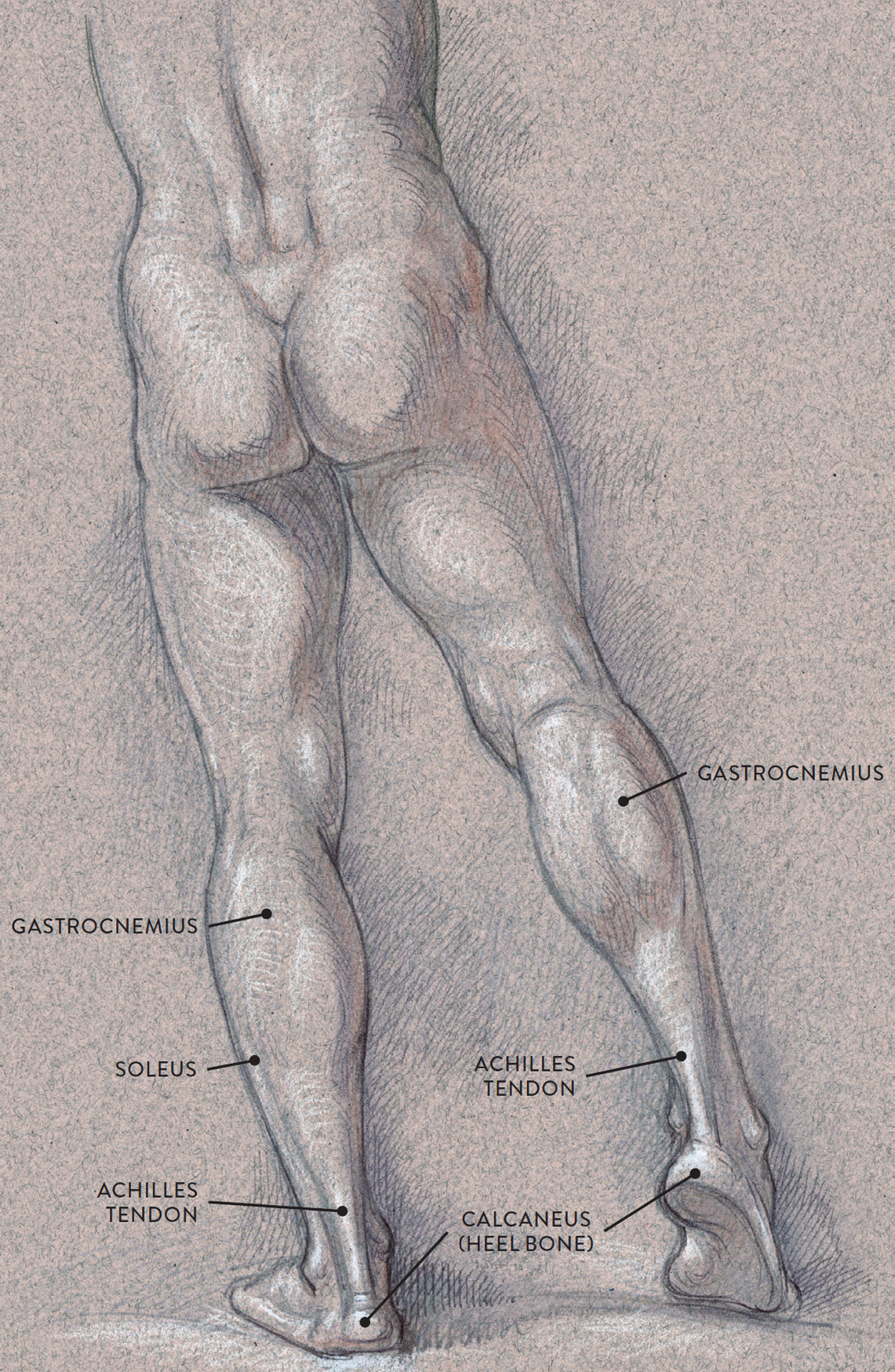

In the following life study Male Figure with Right Leg Positioned on the Ball of the Foot, you can see the rich bulging shape of the gastrocnemius muscle with its tendon (the Achilles tendon) appearing as a thick cord as it inserts into the heel. The accompanying muscle diagram shows the locations of the various surrounding muscles.

MALE FIGURE WITH RIGHT LEG POSITIONED ON THE BALL OF THE FOOT

Graphite pencil, ballpoint pen, watercolor wash, and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The gastrocnemius (pron., gas-trock-NEE-mee-us), more commonly known as the calf muscle, is an impressive oval muscular shape occupying the upper half of the lower leg in the posterior region. The two heads of the gastrocnemius begin on the large condyles of the femur—the lateral head on the lateral condyle and the medial head on the medial condyle. The muscle fibers merge into a common tendon, which inserts into the calcaneus of the foot (heel bone). Its tendon appears as a neutral area until it converges into the thick cordlike form known as the Achilles tendon. The tendon serves as an important landmark for artists as it flows downward from the rich shape of the calf to eventually anchor into the heel bone. The gastrocnemius helps bend the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of the lower leg). When it contracts it also helps raise the heel, which is seen in the action of pointing the foot (plantar flexion) and in the tiptoe position.

The soleus (pron., SO-lee-us or SOL-ee-us) is positioned beneath the gastrocnemius; only its outer and inner borders appear on the surface, as elongated muscular ridges. The soleus shares the same broad tendon with the gastrocnemius. The muscle begins on the fibula, near the head and upper surface of the shaft, as well as on the tibia and the interosseous membrane. It inserts into the calcaneus (heel bone) by way of the Achilles tendon. The soleus helps raise the heel in walking, in standing on tiptoe, and in the action of pointing the foot downward (plantar flexion).

The plantaris (pron., plan-TARE-iss) is a small, somewhat flattened fusiform muscle with an extremely long, slender tendon. It is mostly covered by the lateral head of the gastrocnemius, with only a small portion being exposed near the popliteal fossa. Its presence is noticeable only on muscularly well-defined legs. The muscle begins on the lower part of the femur near the lateral epicondyle. Its tendon attaches into the calcaneus (heel bone). The plantaris’s action is very weak, but it assists in bending the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion) and helps in raising the heel up, which is seen as the action of pointing the foot downward (plantar flexion).

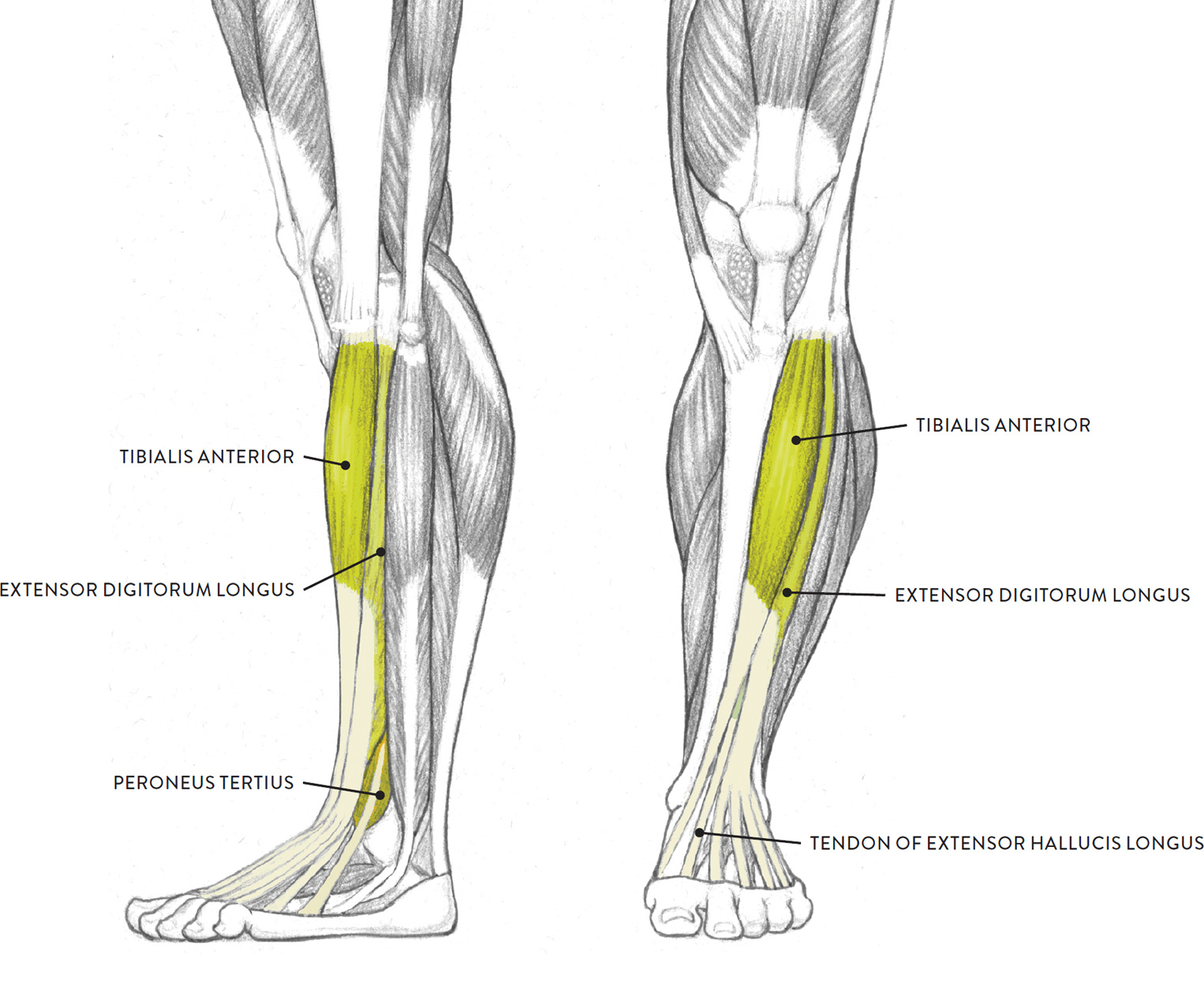

The Extensor Muscle Group of the Lower Leg

Positioned on the front portion of the lower leg, the muscles of the extensor group are the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and extensor hallucis longus, as shown in the following drawing. The peroneus tertius also belongs to the extensor group, although its name might lead you to think that it is part of the peroneal group (see this page). The extensor group muscles help move the foot at the ankle joint and extend the toes.

EXTENSOR MUSCLE GROUP OF LOWER LEG

Left leg, lateral (left) and anterior (right) views

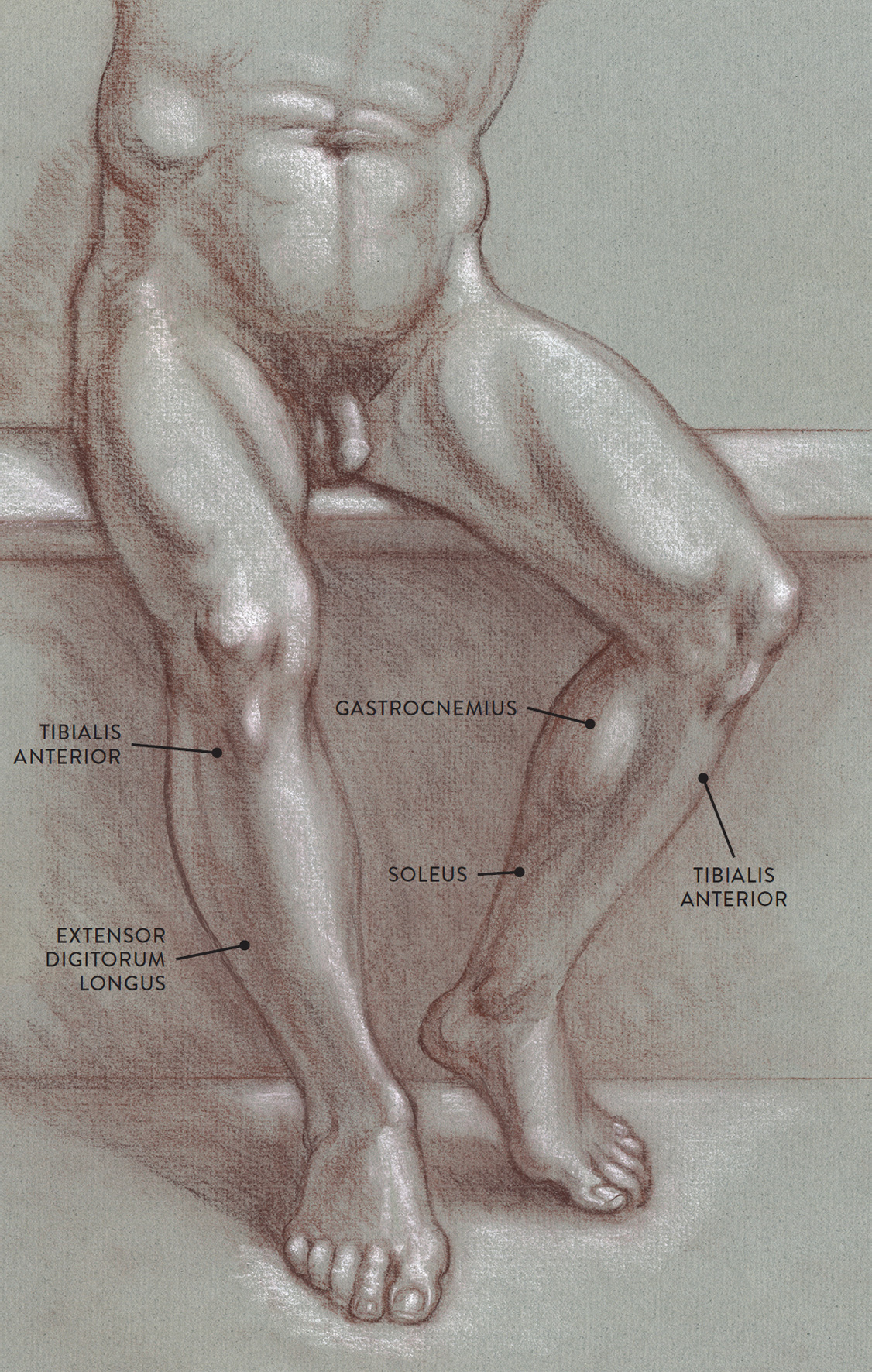

The following life study Lower Torso and Legs in a Frontal View, shows the lower torso of a male figure. The accompanying muscle diagram reveals the position of the muscles of the lower legs in this pose.

LOWER TORSO AND LEGS IN A FRONTAL VIEW

Sanguine and brown pastel pencils, with white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The tibialis anterior (pron., tib-ee-AL-iss an-TEER-ee-or), also known as the shin muscle, is an elongated fusiform muscle that travels down the leg obliquely. Its cordlike tendon is noticeable near the inner ankle joint when the foot is lifted upward. The muscle begins on the tibia and the interosseous membrane. The elongated tendon of the tibialis anterior inserts on the side of the foot on the medial cuneiform tarsal bone and the base of the first metatarsal. The muscle raises the foot upward at the ankle joint (dorsiflexion) and turns the foot in an inward direction (inversion).

The extensor digitorum longus (pron., ek-STEN-sor dij-ih-TOR-um LON-gus) is a slender muscle positioned next to the tibialis anterior on the front of the lower leg. This muscle can appear as an elongated ridge on muscular individuals; on most people, however, it blends with the tibialis anterior. The extensor digitorum longus begins on the tibia and fibula and the interosseous membrane. About halfway down the lower leg the muscle fibers merge into a broad flat tendon, which then splits near the ankle joint into four individual tendons, each inserting into one of the four lesser toes. These tendons are detected on the surface when the toes are spread outward. The extensor digitorum longus raises the foot upward at the ankle joint (dorsiflexion) and also lifts the lesser toes upward (extension).

The extensor hallucis longus (pron., ek-STEN-sor HAL-loo-sis LON-gus or ek-STEN-sor HALL-luc-kiss LON-gus), commonly called the great toe muscle, is positioned beneath and between the tibialis anterior and the extensor digitorum longus. The great toe muscle begins on the fibula and the interosseous membrane. Its muscle fibers are usually not seen on the surface, but its cordlike elongated tendon is visible as it inserts into the large toe, especially when the muscle contracts, lifting the toe. (Many artists mistake this tendon for the tendon of the tibialis anterior, but the tibialis anterior’s tendon, although positioned near the great toe’s tendon at the ankle region, veers off to attach into the inner side of the foot.) The extensor hallucis longus raises the toe (extension of great toe) and also assists in lifting the foot upward (dorsiflexion).

The peroneus tertius (pron., pair-oh-NEE-us TER-shee-us), also known by the older name fibularis tertius, is anatomically part of the extensor muscle group, not the peroneal muscle group. The peroneus tertius begins on the front portion of the fibula and the lower part of the interosseous membrane and inserts into the fifth metatarsal of the foot. Like the peroneus muscles, it helps turn the foot in an outward direction (eversion). And like the extensor muscle group, it helps raise the foot upward from the ankle joint (dorsiflexion).

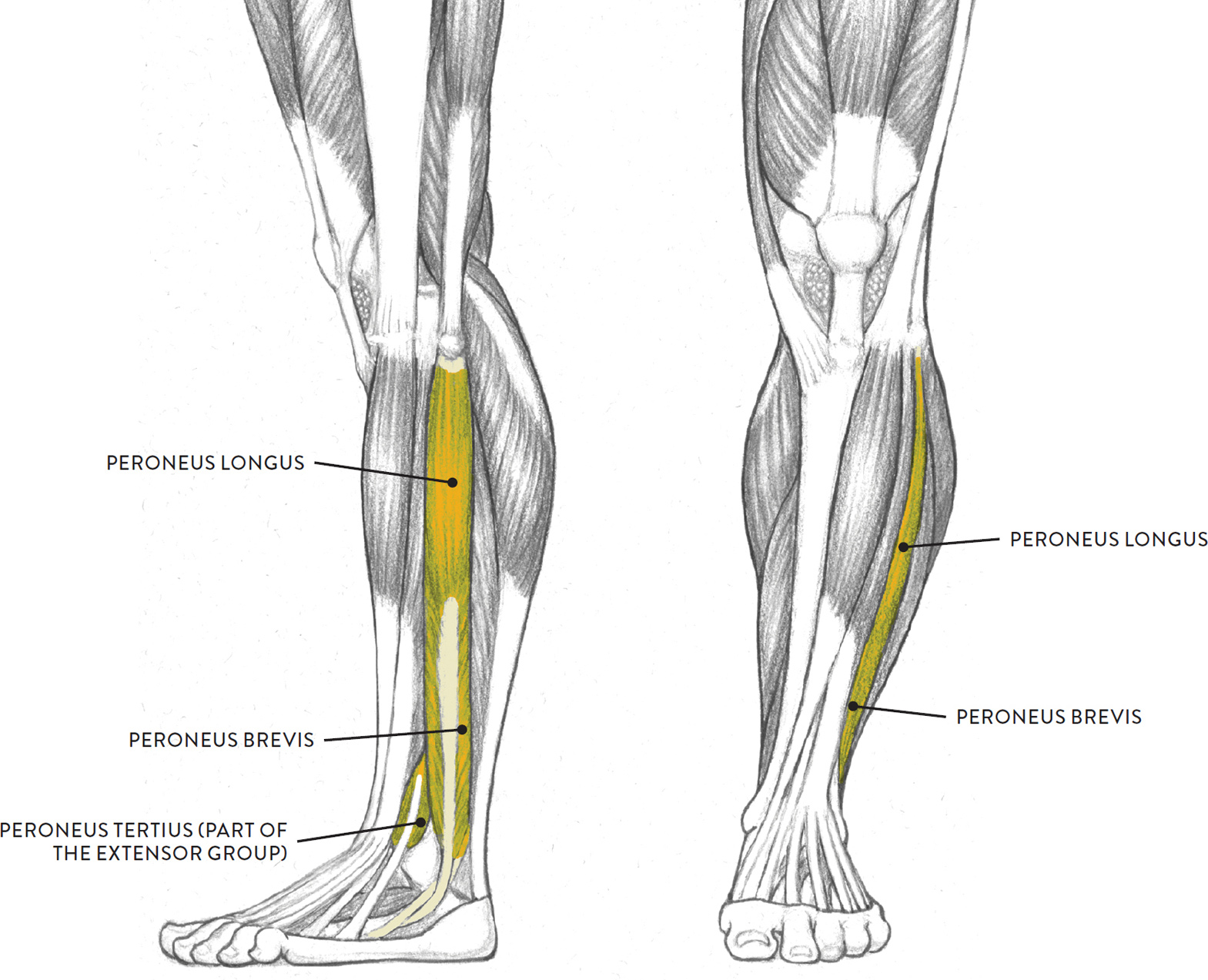

The Peroneal Muscle Group of the Lower Leg

The peroneal group consists of two muscles located on the lateral side of the lower leg: the peroneus longus and the peroneus brevis. Shaped like an elongated bootstrap, the peroneal muscles move the foot at the ankle joint and help stabilize the ankle. They appear as elongated muscular ridges that are more apparent on joggers, bicyclists, and others who use their lower leg muscles extensively.

PERONEAL MUSCLE GROUP OF THE LOWER LEG

Left leg, lateral (left) and anterior (right) views

The peroneus longus (pron., pair-oh-NEE-us LON-gus or pair-RONE-ee-us LON-gus) is the larger of the two peroneal muscles. It is a bipennate muscle with a long, slender tendon, which can be seen riding close to the edge of the fibula, where it wraps around the outer ankle before inserting into the foot. It begins on the head of the fibula and the lateral condyle of the tibia and inserts into the foot at the base of the first metatarsal and the medial cuneiform tarsal bone. The peroneus longus helps point the foot from the ankle joint (plantar flexion) and helps turn the foot outward (eversion).

The peroneus brevis (pron., pair-oh-NEE-us BREV-iss or pair-RONE-ee-us BREH-viss) is also a bipennate muscle. It begins on the lower two-thirds of the fibula and inserts into the base of the fifth metatarsal of the foot. Like its larger partner, it helps point the foot (plantar flexion) and helps turn the foot outward (eversion).

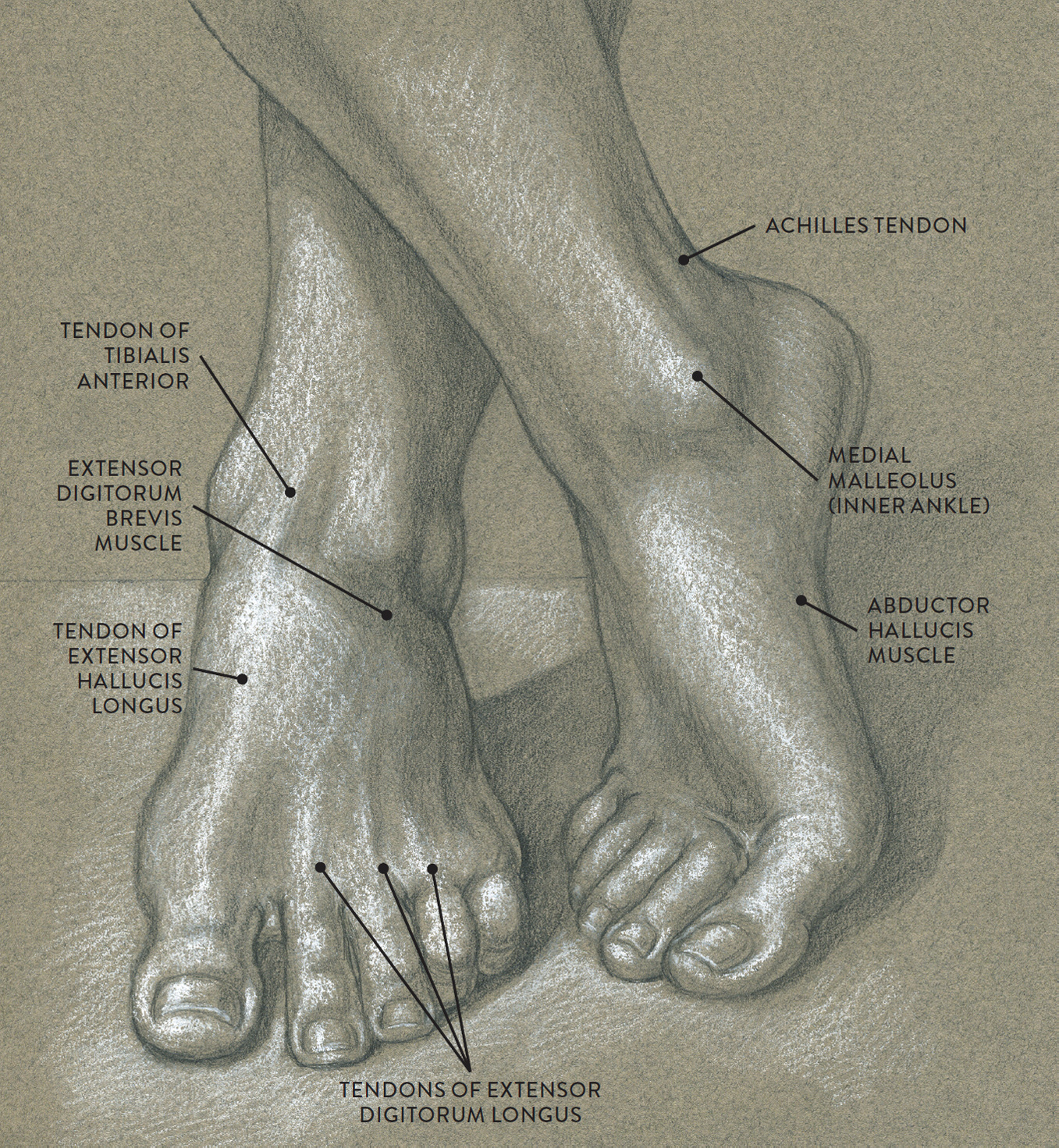

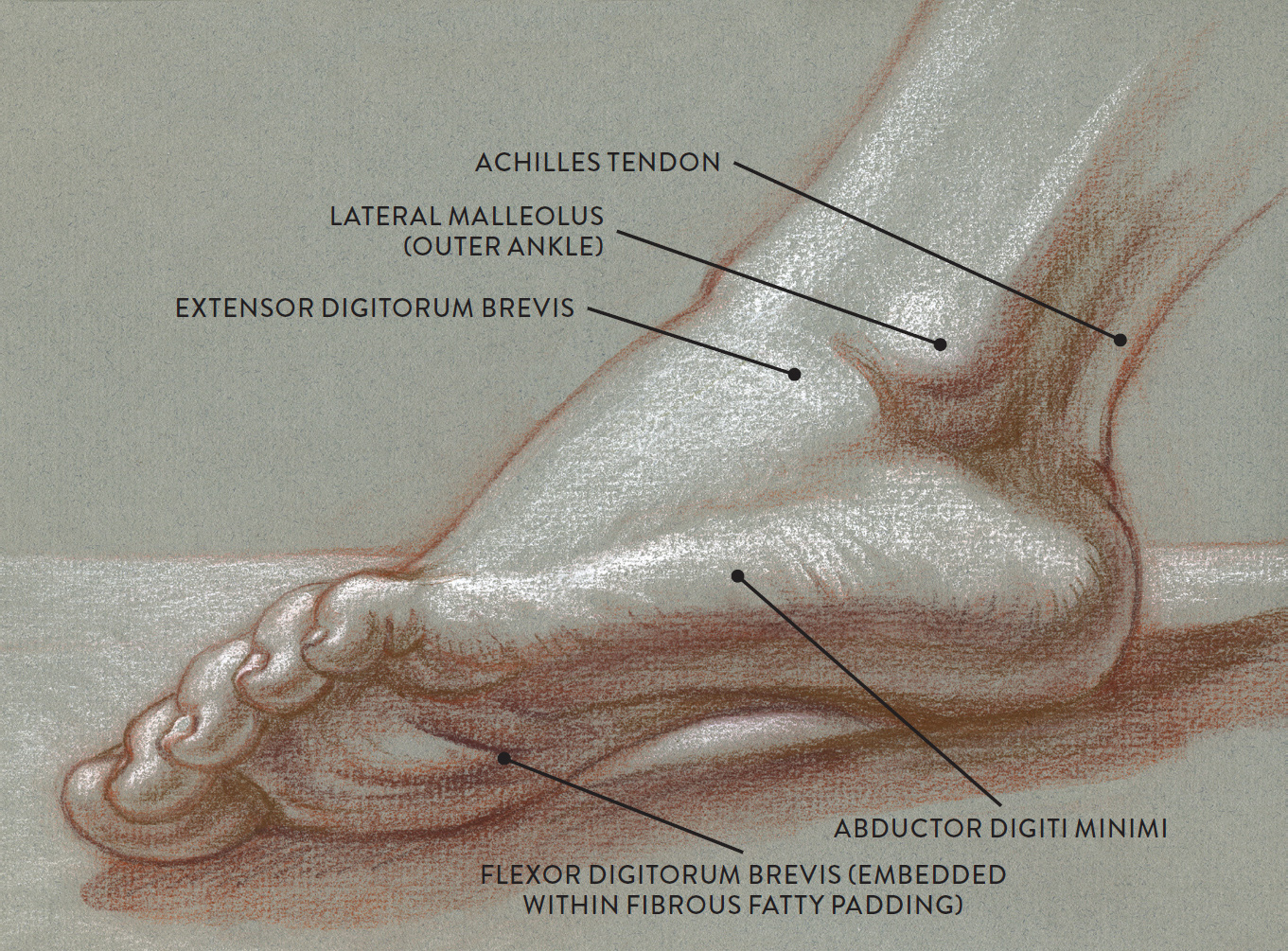

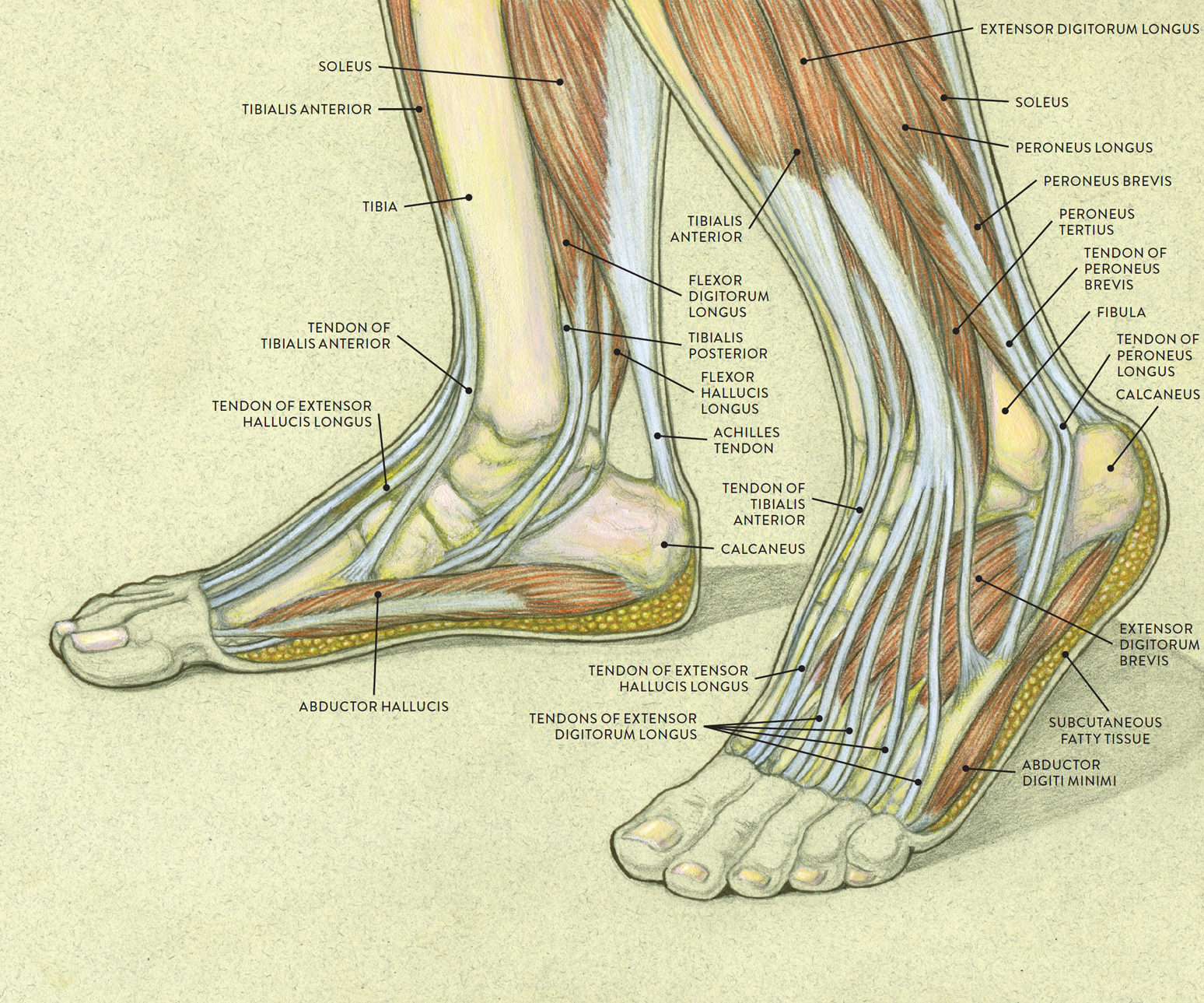

Muscles of the Foot

The foot is a fascinating structure, composed of many bones, ligaments, and cartilages; a few muscles; layers of tendons; and a large amount of fatty tissue that provides shock absorption. The drawing on this page shows the complexity of the foot’s internal structures.

The dorsal (top) part of the foot contains the tendons descending from the muscles of the lower leg, each one continuing into a different toe. These tendons can at times be seen quite clearly, especially when the toes are spread apart (adduction of the toes). The only muscle located on the dorsal region of the foot is the extensor digitorum brevis, which appears as a small, soft, egglike form near the outer ankle bone (lateral mallelous of the fibula). It helps straighten the lesser toes (extension) and is activated in walking and running when the toes are pulled upward to clear the ground.

|

Muscles of the Foot Pronunciation Guide |

|

|

MUSCLE |

PRONUNCIATION |

|

abductor digiti minimi |

ab-DUCK-tor DIH-jih-tee MIN-ih-mee |

|

extensor digitorum brevis |

ek-STEN-sor dij-ih-TOR-um BREV-iss |

|

abductor hallucis |

ab-DUCK-tor HAL-loo-siss |

Along the outer edge of the foot, beginning near the fifth toe and terminating in the heel region, is the abductor digiti minimi. This narrow, streamlined muscle is padded with fatty tissue on its lower border and appears as a noticeable ledge along the outer region of the foot. When this muscle contracts, it pulls the little toe sideways from the foot (abduction) and also helps bend the little toe (flexion).

Another elongated muscle, the abductor hallucis, is attached along the inner arch of the foot and can be seen occasionally. When this muscle contracts it pulls the large toe sideways from the foot (abduction).

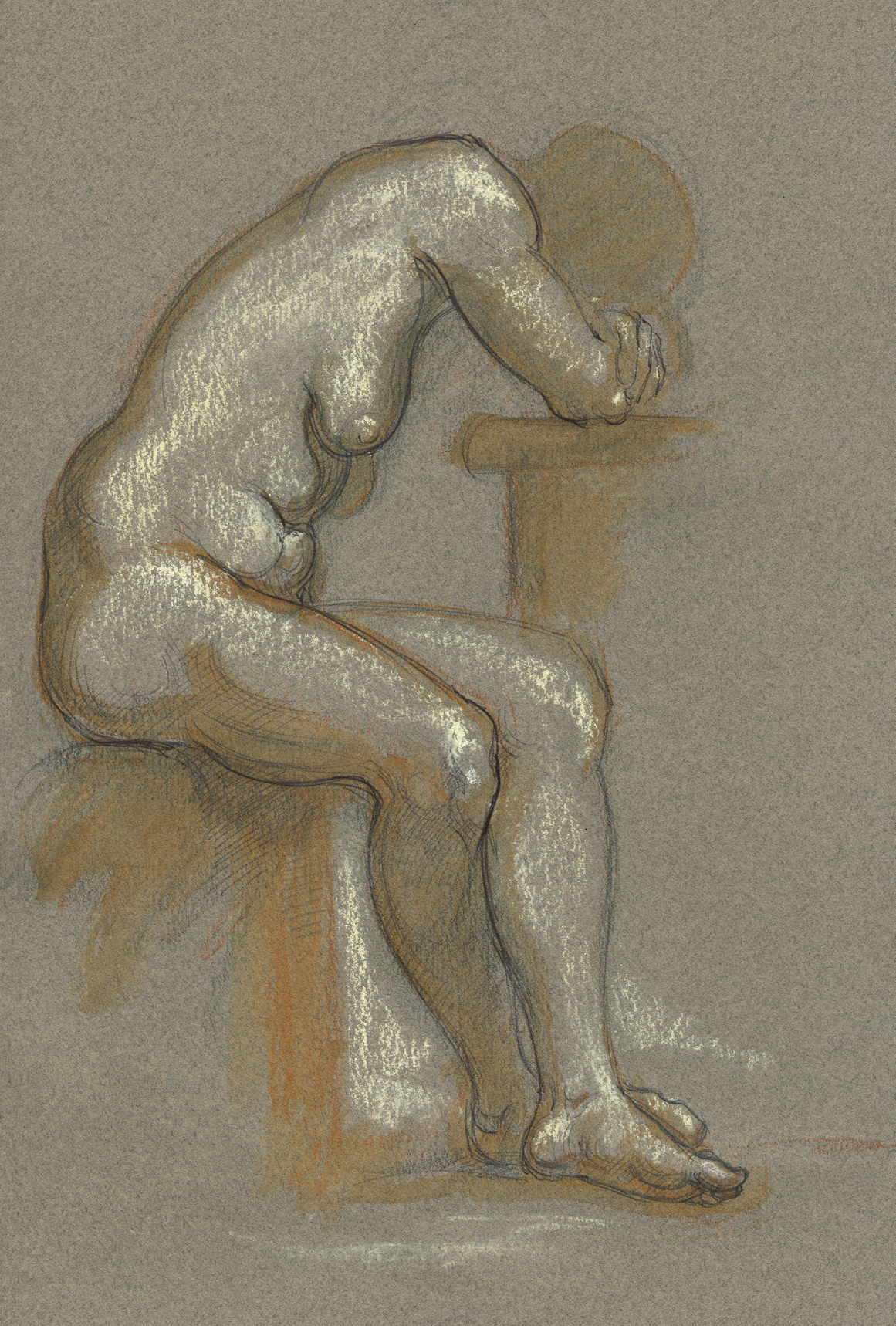

As with the hands, I recommend practicing drawing the feet in many different positions. Sketching the feet from various sources (master artists’ paintings and sculpture, models’ feet, photos) will help you gain confidence and skill when approaching these difficult forms. The studies can be gesture drawings (see this page) that quickly capture the general shape of the foot or longer studies, such as the ones to the right, that emphasize the anatomical forms of the foot.

STUDY OF FEET

Graphite pencil and white chalk on toned paper.

STUDY OF A LEFT FOOT IN A LATERAL VIEW

Sanguine and brown pastel pencils and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLES AND TENDONS OF THE FOOT

LEFT: Medial (inner side) view of right foot

RIGHT: Lateral (outer side) view of left foot

STUDY OF FEMALE FIGURE SITTING, SIDE VIEW

Graphite pencil, ballpoint pen, watercolor pencil, and white chalk on toned paper.