Biology of Humans

2a. Food Safety and Defense

In Chapter 2 we described water’s important functions in the human body. In this chapter, we examine some of the illnesses caused by consuming contaminated food or water. Typical symptoms of these illnesses include vomiting and diarrhea, which can cause dehydration and disrupt body homeostasis. We examine how these illnesses are diagnosed and treated. We also look at the agencies that protect our food supply, and what we can do as individuals to make sure that the food we eat and the water and beverages we drink are safe.

Foodborne Illnesses

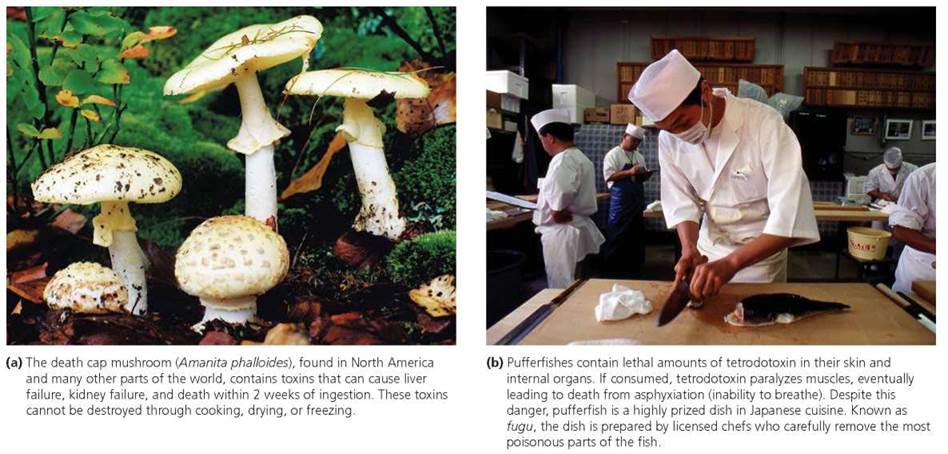

Foodborne illnesses are the result of ingesting contaminated food or water. Disease-causing agents such as bacteria, viruses, prions (infectious proteins), and parasitic protozoans (single- celled eukaryotic organisms) or worms can contaminate food; collectively, these agents are called pathogens. There are more than 250 different foodborne illnesses, including some caused by harmful chemicals such as those found in pesticides or those found naturally in certain mushrooms or fish (Figure 2a.1). Foodborne illnesses caused by pathogens are described as infections, whereas those caused by chemicals or toxins are considered poisonings. The general public usually ignores this distinction and simply refers to all foodborne illnesses as "food poisoning." (Food allergies, described in Chapter 13, are also a type of foodborne illness.)

· Careful food selection, preparation, and storage can help prevent foodborne illness.

FIGURE 2a.1. Naturally occurring poisons can cause foodborne Illness and death.

General Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Despite their different causes and classifications, all foodborne illnesses have symptoms that first appear in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

These early symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea. Some pathogens do not move beyond the GI tract. Other pathogens, including some bacteria, produce toxins that are absorbed into the bloodstream, while still others directly invade other body tissues. For example, the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, found in improperly canned foods, produces a toxin that blocks communication between nerve and muscle cells, causing paralysis of muscles and making it difficult or impossible to breathe. Because new canning procedures have virtually eliminated the risk of botulism from commercially canned foods, foods canned improperly at home are the typical source of C. botulinum contamination (see Chapter 13a for discussion of how bacteria and viruses cause disease).

Many foodborne illnesses go undiagnosed and unreported to public health officials. Some ill people do not seek medical care, perhaps because they do not realize that they have a food- borne illness or because they can't afford to see a doctor. For those who seek medical attention, diagnostic tests may not be performed to confirm the particular illness and its causative agent; or if tests are performed, the results may not be communicated to public health officials. The latter situation can arise because each state decides which diseases should be monitored in that state, so some diseases are not reportable in the first place. Some estimates suggest that the actual number of cases of mild foodborne illnesses is 20 to almost 40 times the numbers reported. Even foodborne illnesses with very severe symptoms are underreported, though to a much lesser degree than those with milder symptoms. In 1996 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and selected state health departments developed FoodNet, a collaborative monitoring system that collects data on pathogens commonly transmitted through food. This program tracks seven bacterial and two parasitic foodborne illnesses, and it picks up illnesses in participating states that are diagnosed but not reported.

A diagnosis of foodborne illness requires a physical exam and additional research to obtain a detailed history of recently consumed foods and beverages. A stool sample may be collected for specific laboratory tests. When a bacterial illness is suspected, stool samples are cultured and the bacteria that grow on the culture medium are identified. If parasites are suspected, then the stool sample is also examined with a microscope. Because parasites often have several life stages, stool samples are examined for the presence of adults or younger stages, such as eggs or larvae. In the case of the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum (a major cause of waterborne diarrheal illness in the United States), trained laboratory personnel look for oocysts, the infectious early stage in the life history of this organism. During the oocyst stage, the parasite is enclosed in a protective capsule that makes it resistant to chlorine-based disinfectants. Cryptosporidium parvum is commonly transmitted through the swallowing of recreational water, such as that found in pools, hot tubs, and ponds. Tests for viruses are more complicated and usually involve testing the stool sample for the genetic markers that indicate the presence of a specific virus. Patients may have a blood sample collected for examination. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the symptoms associated with diarrheal illness that warrant consultation with a health care professional are the following:

• Temperature over 101.5°F (measured orally)

• Blood in stools

• Prolonged vomiting (especially inability to keep liquids down)

• Dizziness when standing up, dry mouth and throat, decreased urination (all indicate dehydration)

• Diarrhea lasting more than 3 days

Recall from Chapter 2 that water performs important functions in our body, such as serving as the main transport medium and helping to prevent dramatic changes in body temperature. The vomiting and diarrhea associated with food- borne illness, while functioning to expel the offending pathogens or toxins from the GI tract, rob the body of water it needs to function properly. Dehydration from diarrhea and vomiting can be deadly if not treated. Patients treated for food- borne illnesses are usually given clear, clean fluids to prevent dehydration. When foodborne illness is caused by bacteria, antibiotics may be prescribed as well. Antiparasitic drugs can be used to kill parasites.

Common Foodborne Infections

The most common foodborne infections in the United States are caused by the bacteria Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli O157:H7, along with a group of viruses known as caliciviruses. Campylobacter jejuni typically enters the body during the handling of raw poultry or the consumption of raw or undercooked poultry (chickens often carry the bacteria but show no signs of illness). The resulting illness is known as campylobacteriosis.

Species of bacteria within the genus Salmonella most often enter our bodies when we consume food contaminated with animal feces. The food, which is often—but not always—animal in origin (meat, milk, or eggs), usually looks and smells normal. The illness that results is salmonellosis.

Most strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli do not cause illness; in fact, E. coli live harmlessly in the intestines of most people. Escherichia coli O157:H7, however, is not harmless (the letters and numbers in its name refer to specific markers found on its surface that allow scientists to differentiate this bacterium from other strains of E. coli). This strain lives in the intestines of healthy farm animals such as cattle, goats, and sheep, and is most commonly passed to humans when they consume undercooked ground beef that contains the pathogen. Escherichia coli O157:H7 also occurs in animals at petting zoos, where it has been found on the animals' fur as well as on the ground, on railings, and in feed bins. Once a person is infected with Escherichia coli O157:H7, good hygiene is necessary to prevent its spread to others. If hand washing is inadequate, Escherichia coli O157:H7 in diarrhea can be passed from person to person.

Finally, viral gastroenteritis, commonly called the stomach flu, is caused by many viruses, including a group known as caliciviruses. Individuals can become infected by consuming food or beverages contaminated with caliciviruses. Viral gastroenteritis is contagious and is spread by close contact with an infected person.

These four common foodborne illnesses—campylobacteriosis, salmonellosis, infection with Escherichia coli O157:H7, and viral gastroenteritis—have similar symptoms: diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps. Fever is present in some cases. Campylobacter and Salmonella infections that spread beyond the GI tract to the bloodstream are more serious, and infection with Escherichia coli O157:H7 occasionally causes kidney failure. All but caliciviruses can cause life-threatening illness. People most at risk include those whose immune system is compromised or incompletely developed, such as the very old, the very young, and those already suffering from a disease that reduces their immune function. However, even healthy people can die from foodborne illnesses if they are exposed to a very high dose of the pathogen, or if they do not receive proper treatment.

How Does Food Become Contaminated?

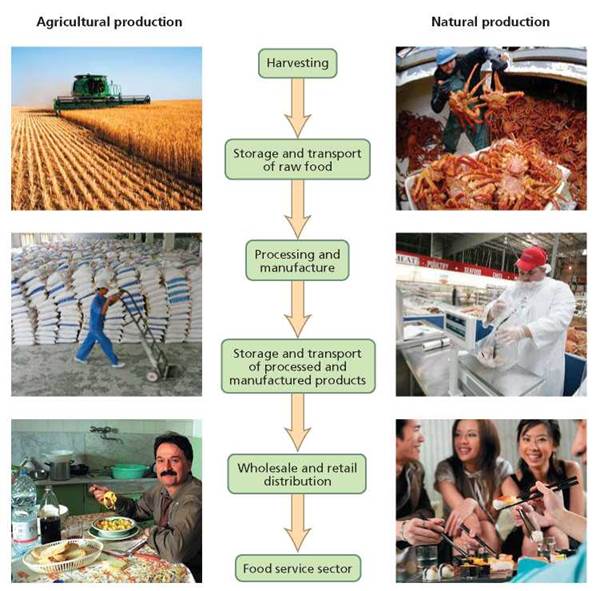

Food can become contaminated during any of the many steps that typically occur as it moves from "farm to fork" (Figure 2a.2). At early stages, bacteria normally present in the intestines of food animals, such as cows or chickens, can contaminate carcasses at slaughterhouses and get into meat and poultry products. Salmonella can infect the ovaries and oviducts of chickens, which then produce eggs containing the bacterium. This route of infection, called the "transovarian" route, is thought to be the predominant way that eggs become contaminated. A less common route, called the "trans-shell" route, occurs when bacteria in the environment, such as those on nesting material or in shipping containers, penetrate the eggshell after the egg has been laid.

FIGURE 2a.2. A typical pattern of steps by which food moves from harvesting to consumption.

Oysters and other filter-feeding shellfish concentrate bacteria naturally found in seawater along with the bacteria dumped into our oceans in human sewage. Oysters also concentrate toxins and pollutants. Large individuals of some top predatory fish species in our oceans, such as king mackerel, act as bioconcentrators and store potentially dangerous levels of heavy metals (such as mercury) in their tissues (see Chapter 23). In freshwater and on land, parasitic worms, such as roundworms, tapeworms, and flukes, release eggs into the environment where they may be picked up by other animals including fish, pigs, and cattle. The eggs of the parasitic worms hatch into larvae in these animals, and the larvae can survive for some time after the animals have been killed for food.

Certain foods are more likely than others to be associated with foodborne illness. As evident from our discussion, raw foods originating from animals are most likely to be contaminated. In addition, foods that contain the products of many animals, such as ground beef, are especially dangerous because only one of the many contributing animals need contain the pathogen for the meat to be contaminated. To put this in perspective, it is estimated that a single hamburger patty may contain meat from hundreds of cattle, and a glass of milk may contain milk from hundreds of cows!

Contamination is not restricted to food from animals. Indeed, fresh fruits and vegetables can become contaminated with bacteria, viruses, and protozoan parasites when they are irrigated or washed with water containing animal (including human) waste. For example, fresh spinach contaminated with E. coli O157:H7 killed three people and sickened about 200 others in an outbreak that spanned 26 states in the fall of 2006. Investigators were able to trace the contaminated spinach back to at least one field and farm in California, where tests of soil, water, and animal manure showed that E. coli O157:H7 was more widespread in the environment than previously believed. Washing fruits and vegetables may not protect against foodborne illness. Contaminated water can introduce pathogens to produce, and washing with clean water has been shown to decrease but not to completely eliminate contamination. Produce also may contain residues of pesticides, chemicals used to kill organisms that damage crops.

Food also can be contaminated during processing (refer, again, to Figure 2a.2). For example, from fall 2008 through spring 2009, peanut butter and peanut paste contaminated with Salmonella sickened more than 700 people in 46 states and may have contributed to eight deaths. The contamination was traced to a peanut processing plant in Georgia and may have resulted from improper roasting or subsequent processing. Finally, food also can be contaminated during preparation. People handling food with unwashed hands can introduce pathogens, and pathogens can be transferred from one food to another when utensils and cutting boards are used for different foods without being washed in between.

Methods of Combating Food Contamination

Once food is contaminated, the way it is handled becomes critical. Large numbers of bacteria are usually required to cause foodborne illness, so leaving contaminated food in conditions conducive to bacterial reproduction is especially dangerous. Bacteria reproduce extremely rapidly, particularly under warm, moist conditions (temperatures between 40 and 140°F are considered the danger zone because they represent conditions under which bacteria are most likely to reproduce). In fact, a single bacterium reproducing by binary fission (dividing itself in half) can produce millions of new cells in only a few hours (see Chapter 13a).

Prompt refrigeration can slow reproduction by many bacteria, as can acidic conditions. Most microorganisms do not thrive at a pH of less than or equal to 5. To create such acidic conditions, vinegar (which is dilute acetic acid) is often added to such foods as cucumbers and peppers during a process called pickling. High levels of salt or sugar also can be used to inhibit microbial growth in food; these solutes reduce the amount of water available to microorganisms. Fruits are typically preserved by adding sugar (to make jams and jellies), and meats and fish are often preserved with salt. Drying also reduces water available to microorganisms, and this method is used to preserve fruits, vegetables, meat, fish, eggs, and milk.

With few exceptions, parasites, bacteria, and viruses are killed by heat; the microorganisms die because very high temperatures cause their macromolecules, such as DNA and proteins, to lose their structure and function. In this way, heating contaminated food to sufficiently high temperatures can render it safe to eat. A food thermometer, placed in the thickest part of the food item, should reach at least 160°F to ensure that the food item is safe to eat. Toxins produced by bacteria vary in whether or not they are destroyed by heat. Prions are not destroyed by heat alone. However, research in the last few years has shown that the combination of high temperature (250-275°F) and short bursts of very high pressure, a technique used commercially to kill bacteria in food, also inactivates prions in processed meats, such as hot dogs. Prions also are inactivated by treatment with certain very strong chemicals, such as sodium hydroxide (a strong base) and household bleach, but such treatments cannot be applied to food.

Stop and think

Sponges used to clean kitchen countertops have a reputation for being notoriously contaminated items. What characteristics associated with sponges and their use lead to such high levels of contamination? What could we do to prevent or reduce their contamination?

Keeping Food Safe at International and National Levels

Our food supply today is global: Most of us consume food grown and processed in other countries as well as that produced nearer to home. It is not unusual, for example, for us to consume grapes and strawberries from Chile or salmon from Norway. The nature of our food supply, along with the extreme mobility of people, makes the regulation of food safety and the tracking of food- borne illnesses extremely challenging. To this end, several agencies regulate, monitor, and investigate the safety of our food.

International Oversight

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a United Nations agency whose primary mandate is to protect public health. One of its major tasks is to fight diseases, especially those that are communicable (able to be passed from one person to another). Various functions of WHO regarding food safety include coordinating international efforts to effectively monitor and respond to outbreaks of foodborne illness and implementing international health regulations. These regulations relate to international travelers and the import and export of contaminated foods. WHO also sponsors research on foodborne illnesses and programs to prevent and treat these illnesses.

National Oversight

Several agencies within the United States are charged with overseeing food safety. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for the safety of about 80% of our food supply. More specifically, the FDA oversees all domestic and imported food except meat and poultry. In addition, the FDA oversees eggs (in the shell), bottled water, and wines containing less than 7% alcohol. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) oversees all other alcoholic beverages. The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) oversees domestic and imported meat and poultry, including products that contain meat or poultry such as frozen foods. Processed egg products (such as liquid egg whites) are also overseen by the FSIS. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates the use of pesticides in agriculture and establishes standards for safe public drinking water. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) inspects fishing vessels and seafood processing plants. Finally, the Customs Service works with federal regulatory agencies to make sure the imported foods meet the regulations of the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is not a regulatory agency, in the sense that it does not have the power to enforce federal rules. Nevertheless, it plays a critical role in keeping our food safe by working with state and local health officials to monitor the occurrence of foodborne illnesses (as well as other diseases). Another major function of the CDC is to investigate disease outbreaks. Working with local food safety officials, the CDC determines whether a cluster of similar cases suggests an outbreak of foodborne illness in a particular area. When an outbreak is suspected, the CDC begins an investigation to determine the particular pathogen involved and its source. Such investigations typically involve searching for more cases; characterizing the outbreak by time, place, and people involved; identifying the pathogen through laboratory tests performed on stool or blood samples; and determining through extensive interviews the source of the outbreak. The CDC also develops methods to prevent foodborne illnesses and continually assesses the effectiveness of prevention efforts. Because the CDC does not restrict its oversight activities to particular foods, it effectively oversees all foods.

Food Defense and Bioterrorism

So far we have considered unintentional threats to our food and water supplies, such as pathogens accidentally entering food or people mistakenly eating food that contains toxins. However, intentional threats also exist. For example, there is considerable concern that terrorists could introduce into food or water supplies biological, chemical, or radiological agents with the goal of generating fear, economic losses, and human casualties. Whereas food safety prevents the unintentional contamination of food, food defense prevents deliberate contamination. Here we consider food defense, which is overseen by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and many of the agencies previously described as overseeing food safety. The DHS has many food defense responsibilities, including development of screening procedures for food entering the United States, assessing the vulnerabilities of the food and beverage industries, and coordinating efforts by the private sector and federal, state, and local governments to protect these industries.

Bioterrorism is the use of biological agents (bacteria and their toxins, viruses, or parasites) to intimidate or attack societies or governments. The CDC classifies biological agents that could be used in terrorist attacks into three categories (A, B, and C) based on characteristics of the biological agent such as availability, ease of dissemination (distribution), severity of health effects produced, and degree of preparedness required by public health agencies to respond to an attack.

Biological agents in Category A are the highest priority because they are easily disseminated or highly transmissible from person to person, produce high mortality rates, and require significant planning by public health agencies. Included in Category A is the toxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. This toxin is the most poisonous substance known. Although the resulting illness (botulism) is not spread from person to person, the agent is placed in this category because of its extreme potency and lethality, and because it can so easily be produced and transported. We mentioned earlier in this chapter that the toxin might enter food unintentionally as a result of improper canning, but it could also intentionally be placed in food. It is unlikely to be placed in water because standard water treatment processes, such as chlorination, inactivate it.

Biological agents in Category B are moderately easy to disseminate, and they result in moderate rates of morbidity (sickness) and low rates of mortality. Included in Category B are several species of bacteria that could be intentionally added to food, including Salmonella and Escherichia coli O157:H7. The main threats to water safety also are included in Category B. These include the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, which causes the acute diarrheal illness cholera, and the single-celled parasite Cryptosporidium parvum, discussed earlier as a major cause of waterborne illness.

Biological agents in Category C include emerging pathogens that could be used in the future because they are easy to produce and disseminate, and they are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality.

Personal Food Safety

Regardless of whether a risk is intentional or unintentional, systems are in place to limit exposure to contaminated food or water. While we may be uneasy about the many steps between the production of food and its arrival on our plate, each of us can do some things to make sure that the food we consume is as safe as possible.

Good personal food safety practices begin with a common- sense approach and the awareness that you should practice food safety from the moment you select an item in a market until you prepare it at home and store the leftovers.

Food Selection

Being informed and taking responsibility for your food selections will help you make better choices. When selecting any food, you should always look at "sell-by" dates and carefully examine the packaging for damage or tampering. Bacterial contamination and the possible growth of bacteria on food surfaces of fresh meat, poultry, seafood, or other food products rich in animal proteins is a very real concern. To limit bacterial growth, we rely primarily on cold temperatures in store display cases, rapid (and cool) transport of food from the store to a home refrigerator, and consistently cold temperatures in home refrigerators (always below 40°F).

Meat. A good rule of thumb when buying meat products is that whole cuts, such as steaks or roasts, are far less likely to carry bacterial contamination than are ground meat products. This is so because the surface area of the food serves as the site for bacterial contamination, and ground meat products have many times the surface area of an equivalent weight of steak. Recall, also, that meat from many individual animals goes into ground meat, raising the chances of pathogens being present in the first place.

Poultry. Fresh poultry is susceptible to bacterial contamination, particularly by Salmonella. Processors now deliver many fresh poultry items to markets packaged in trays or strong bags that limit the contact and potential cross-contamination by bacteria from one item to another. That said, it is impossible to eliminate all risk, and you should not assume that the outside of the package does not harbor bacteria. When you select poultry from a market case, it is a good idea to place it apart from other foods—particularly vegetables or fruits that will be eaten raw—and to clean your hands before handling other food products. Always carry poultry products in bags separate from the rest of the groceries.

Seafood. Shopping for seafood poses some special concerns. For example, some seafood, such as fresh oysters, is traditionally eaten raw; so we cannot rely on high temperatures during cooking to kill pathogens or to destroy their toxins (Figure 2a.3). Also, as noted earlier, oysters as filter feeders concentrate local microorganisms, toxins, and pollutants in their tissues. If you choose to eat raw oysters, then you should ask where the oysters came from. Even when you "know" their source, you must still be willing to accept the risk that the source may not be the pristine natural environment you might assume it is. When you are selecting fresh fish, keep in mind that firmness, color, and odor are paramount. Reject any fish with a strong fishy odor. (Fresh saltwater fish smells like the sea.) You may also want to ask if the fish has been refreshed with any solutions. Such "refreshing" refers to washing the fish with a dilute bleach solution to eliminate bacterial contamination on the surface—not a very appetizing way to treat any food, and not even necessary if the fish has been handled carefully up to that point. (A quick sniff will often reveal the presence of bleach.)

FIGURE 2a.3. Eating raw oysters poses certain risks because oysters are filter feeders that concentrate bacteria, toxins, and pollutants in their tissues.

A final concern when buying fresh fish—even fish that will be cooked to high enough temperatures to ensure safety from typical bacterial contamination—relates to the species of fish you are selecting. As mentioned earlier, large individuals of some top predator species concentrate and store potentially dangerous levels of mercury in their tissues. To avoid consuming dangerous levels of mercury, be aware of the current safety concerns related to individual species of fishes, and do not exceed the recommended weekly consumption rates for those species, especially if you are pregnant or nursing. Further information on mercury contamination is available at the FDA's Food Safety website (www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/Product-SpecificInformation/ Seafood/default.htm), and information regarding the safety of locally caught fish can be found at the EPA's Fish Advisory website (www.epa.gov/waterscience/fish).

Produce. Shopping for fresh vegetables to be consumed raw has been greatly simplified in recent years. Prepacked, prewashed lettuce and salad mixes vie for our attention against whole lettuces and other vegetables. Should you buy the time-saving prepacked versions, whose labels often promise they have been washed twice? From a food safety standpoint, there is no one clear answer. Bacterial contamination of fresh vegetables can happen at many points between farm and fork. Wash even these products that are packaged as ready to eat as thoroughly as possible before consumption, while recognizing that there is always some risk.

What would you do?

Conventionally produced fruits and vegetables are treated with pesticides, exposed to herbicides, and depend upon chemically produced fertilizers derived from finite resources, such as fossil fuels. Washing such produce with running water (and a brush if the fruit or vegetable is firm), peeling fruits whenever possible, and discarding the outer leaves of vegetables such as lettuce, can reduce your exposure to pesticides and herbicides. Some consumers, concerned with chemical residues in fruits and vegetables, select certified organic foods, which are produced without certain synthetic pesticides and fertilizers (some synthetic pesticides have been approved for use on organic farms and are sometimes used). At present, there is no evidence that organic foods are safer or nutritionally superior to conventionally produced foods. Each consumer will have to decide whether to accept fruits and vegetables grown in a conventional manner or to pay somewhat more for foods produced organically. A deciding factor for many consumers is that foods that are certified to have been produced organically may be less harmful to natural environments than are conventionally produced foods. Organically grown products are often produced closer to home, leading to lower oil consumption during transport. The locavore movement grew out of the desire to eat foods produced close to home. Indeed, in the fall of 2009 the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced its “Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food” initiative, which is designed to support development of local agriculture by helping Americans connect with their local farmers. Would you be willing to spend more money on organically produced food? Why or why not?

In addition to concerns about pesticide and herbicide exposure, there are concerns related to genetically modified (GM) foods and to foods that result from the cloning of animals; all of these issues ensure that many basic questions about food safety and the environment will continue far into the future (see Chapter 21 for a discussion of genetically modified food). As a responsible consumer, it is important to stay informed and to make conscientious decisions about your personal tolerance for food safety risks and the future of foods and the environment.

Food Handling and Storage

At home, safe food-handling practices can be sorted into four basic categories: (1) cleanliness, (2) separation, (3) cooking, and (4) chilling (Figure 2a.4). Cleanliness refers to both hand washing by the food preparer (and subsequently the food consumer) and cleanliness of surfaces that will come into contact with raw food, such as cutting boards, knives, and storage containers. Keeping the kitchen workplace clean is an obvious and basic way to improve food safety at home. Separation refers to keeping foods apart from one another and avoiding cross-contamination. For example, keeping fresh meat out of direct contact with cooked foods is an essential part of kitchen hygiene that can limit exposure to bacteria. Cooking refers to thoroughly cooking food products to temperatures that will kill most bacteria, which generally do not survive temperatures greater than 160°F. Proper and prompt chilling of both fresh and cooked foods helps to stop bacterial growth. Nevertheless, even refrigerated food is not safe to eat indefinitely (Table 2a.1). Freezing to 0°F inactivates bacteria in food, but it does not kill them. Indeed, once the food is thawed, the bacteria will begin to reproduce at room temperature. When in doubt about the freshness of refrigerated food, throw it out.

FIGURE 2a.4. This logo from the Be Food Safe program of the USDA and Partnership for Food Safety Education emphasizes the four basic ways to keep food safe at home.

Explain the different effects that chilling and cooking have on bacteria in food. Also, is it best to thaw food in the refrigerator or on the counter in your kitchen?

A Placing food in the refrigerator or freezer does not kill bacteria; it simply stops bacteria from increasing in number. Cooking food to an appropriate temperature kills bacteria. Food should always be thawed in the refrigerator because room temperatures allow bacteria to multiply on the surface of the food, even if the interior is still frozen.

TABLE 2a.1. Storage Times for Refrigerated Foods

Foods |

Storage Times |

Eggs |

|

Fresh, in shell |

3-5 weeks |

Raw yolks, whites |

2-4 days |

Hard-cooked |

1 week |

Liquid pasteurized eggs, egg substitutes |

Unopened, 10 days Opened, 3 days |

Cooked egg dishes |

3-4 days |

Mayonnaise, commercial, opened |

2 months |

Deli and Vacuum-Packed Products |

|

Store-prepared (or homemade) egg, chicken, tuna, ham, and macaroni salads |

3-5 days |

Prestuffed pork, lamb chops, and chicken breasts |

1 day |

Store-cooked dinners and entrees |

3-4 days |

Commercial brand vacuum-packed dinners with USDA seal, unopened |

2 weeks |

Raw Hamburger, Ground and Stew Meat |

|

Ground beef, turkey, veal, pork, lamb |

1-2 days |

Stew meats |

1-2 days |

Ham, Corned Beef |

|

Ham, canned, labeled “Keep Refrigerated” |

Unopened, 6-9 months Opened, 3-5 days |

Ham, fully cooked, whole |

7 days |

Ham, fully cooked, half |

3-5 days |

Ham, fully cooked, slices |

3-4 days |

Corned beef in pouch with pickling juices |

5-7 days |

Hot Dogs and Luncheon Meats |

|

Hot dogs |

Unopened package, 2 weeks Opened package, 1 week |

Luncheon meats |

Unopened package, 2 weeks Opened package, 3-5 days |

Bacon and Sausage |

|

Bacon |

7 days |

Sausage, raw from meat or poultry |

1-2 days |

Smoked breakfast links, patties |

7 days |

Summer sausage labeled “Keep Refrigerated” |

Unopened, 3 months Opened, 3 weeks |

Hard sausage (such as pepperoni) |

2-3 weeks |

Cooked Meat, Poultry, and Fish Leftovers |

|

Pieces and cooked casseroles |

3-4 days |

Gravy and broth, patties, and nuggets |

1-2 days |

Soups and stews |

3-4 days |

Fresh Meat (Beef, Veal, Lamb, and Pork) |

|

Steaks, chops, roasts |

3-5 days |

Variety meats (tongue, kidneys, liver, heart, chitterlings) |

1-2 days |

Fresh Poultry |

|

Chicken or turkey, whole |

1-2 days |

Chicken or turkey, parts |

1-2 days |

Giblets |

1-2 days |

Fresh Fish and Shellfish |

|

Fresh fish and shellfish |

1-2 days |

Source: USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service, Fact Sheets: Safe Food Handling, www.fsis.usda.gov.

Stop and think

When freezing a large amount of food, it is best to divide the food into smaller portions and freeze each portion in a freezer-safe container. Why would freezing multiple, small portions be better than freezing one large portion?

In the end, personal food safety practices when shopping, preparing, and storing foods at home play a major role in ensuring that your food is safe. Keep these principles in mind when you plan, shop for, and prepare safer meals.

Looking ahead

In Chapter 2a we learned about how pathogens, such as certain bacteria and parasitic protozoans, cause foodborne illnesses. These two groups of organisms represent the two basic types of cells: Bacteria are prokaryotes and protozoans are eukaryotes. The cells of the human body are also eukaryotic. In Chapter 3 we describe the basic differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, and then focus on eukaryotic cell structure, function, and energy processing.