THE LIVING WORLD

Unit Four. The Evolution and Diversity of Life

14. Evolution and Natural Selection

14.2. Darwin’s Evidence

One of the obstacles that had blocked the acceptance of any theory of evolution in Darwin’s day was the incorrect notion, widely believed at that time, that the earth was only a few thousand years old. The discovery of thick layers of rocks, evidences of extensive and prolonged erosion, and the increasing numbers of diverse and unfamiliar fossils discovered during Darwin’s time made this assertion seem less and less likely. The great geologist Charles Lyell (1797-1875), whose Principles of Geology (1830) Darwin read eagerly as he sailed on HMS Beagle, outlined for the first time the story of an ancient world in which plant and animal species were constantly becoming extinct while others were emerging. It was this world that Darwin sought to explain.

What Darwin Saw

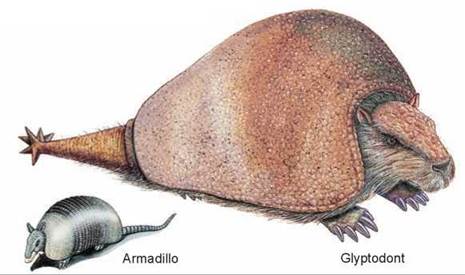

When HMS Beagle set sail, Darwin was fully convinced that species were immutable, meaning that they were not subject to being changed. Indeed, it was not until two or three years after his return that he began to seriously consider the possibility that they could change. Nevertheless, during his five years on the ship, Darwin observed a number of phenomena that were of central importance to him in reaching his ultimate conclusion. For example, in the rich fossil beds of southern South America, he observed fossils of the extinct armadillo shown on the right in figure 14.4. They were surprisingly similar in form to the armadillos that still lived in the same area, shown on the left. Why would similar living and fossil organisms be in the same area unless the earlier form had given rise to the other? Later, Darwin’s observations would be strengthened by the discovery of other examples of fossils that show intermediate characteristics, pointing to successive change.

Figure 14.4. Fossil evidence of evolution.

The now-extinct glyptodont was a large 2,000-kilogram South American armadillo (about the size of a small car), much larger than the modern armadillo, which weighs an average of about 4.5 kilograms and is about the size of a house cat. The similarity of fossils such as the glyptodonts to living organisms found in the same regions suggested to Darwin that evolution had taken place.

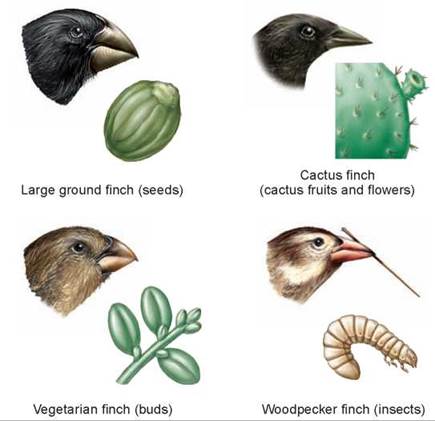

Repeatedly, Darwin saw that the characteristics of similar species varied somewhat from place to place. These geographical patterns suggested to him that organismal lineages change gradually as individuals move into new habitats. On the Galapagos Islands, 900 kilometers (540 miles) off the coast of Ecuador, Darwin encountered a variety of different finches on the islands. The 14 species, although related, differed slightly in appearance. Darwin felt it most reasonable to assume all these birds had descended from a common ancestor blown by winds from the South American mainland several million years ago. Eating different foods, on different islands, the species had changed in different ways, most notably in the size of their beaks. The larger beak of the ground finch in the upper left of figure 14.5 is better suited to crack open the large seeds it eats. As the generations descended from the common ancestor, these ground finches changed and adapted, what Darwin referred to as “descent with modification”—evolution.

Figure 14.5. Four Galapagos finches and what they eat.

Darwin observed 14 different species of finches on the Galapagos Islands, differing mainly in their beaks and feeding habits. These four finches eat very different food items, and Darwin surmised that the very different shapes of their beaks represented evolutionary adaptations improving their ability to do so.

In a more general sense, Darwin was struck by the fact that the plants and animals on these relatively young volcanic islands resembled those on the nearby coast of South America. If each one of these plants and animals had been created independently and simply placed on the Galapagos Islands, why didn’t they resemble the plants and animals of islands with similar climates, such as those off the coast of Africa, for example? Why did they resemble those of the adjacent South American coast instead?

Key Learning Outcome 14.2. The fossils and patterns of life that Darwin observed on the voyage of HMS Beagle eventually convinced him that evolution had taken place.