THE LIVING WORLD

Unit Eight. The Living Environment

37. Behavior and the Environment

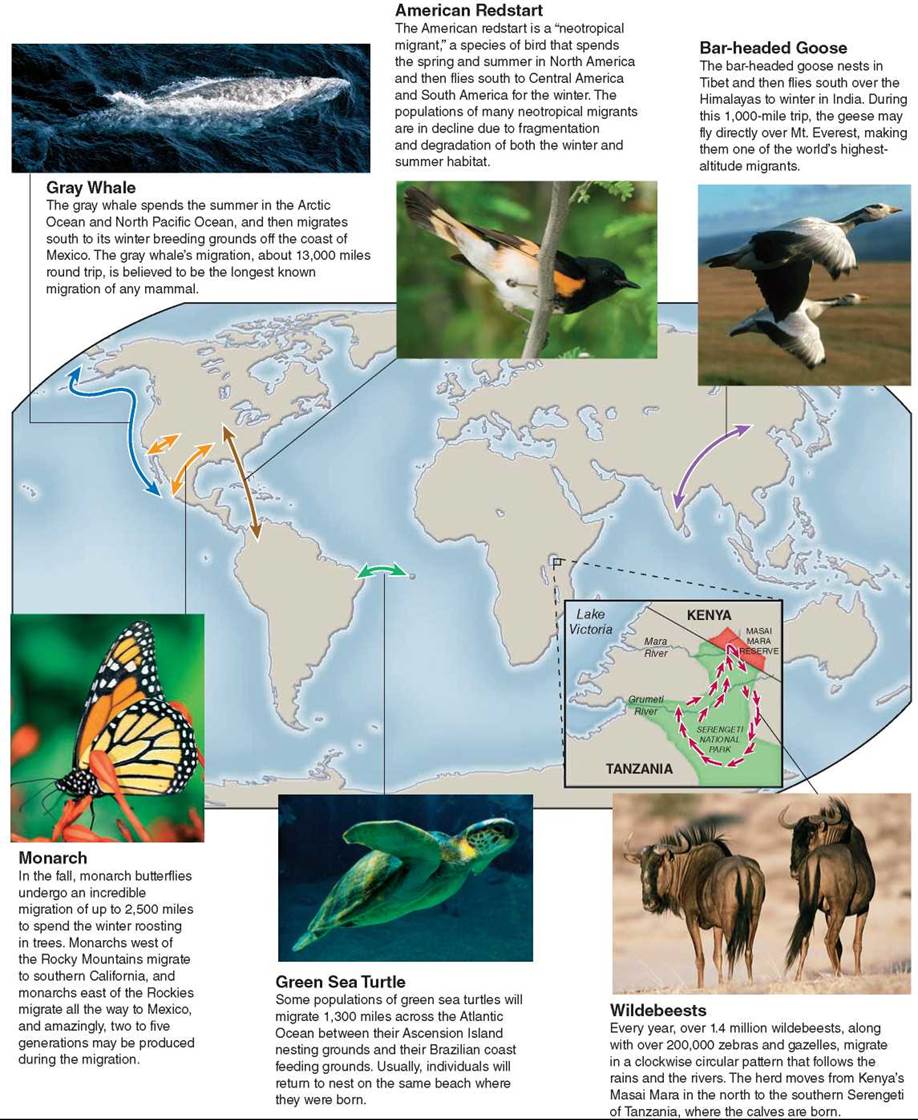

Many animals breed in one part of the world, and spend the rest of the year in another. Long-range, two-way annual movements like this are called migrations (see figure 37.11). Migratory behavior is particularly common in birds. Ducks and geese migrate southward along flyways from northern Canada across the United States each fall, overwinter, and then return northward each spring to nest. Warblers and many other insect-eating songbirds winter in the tropics and breed in the United States and Canada in spring and summer, when insects are plentiful. Monarch butterflies migrate each fall from central and eastern North America to overwinter in several small, geographically isolated areas of coniferous forests in the mountains of central Mexico. Gray whales feed in summer in the Arctic Ocean, then swim 10,000 kilometers to the warm waters off Baja, California, where they breed during winter months.

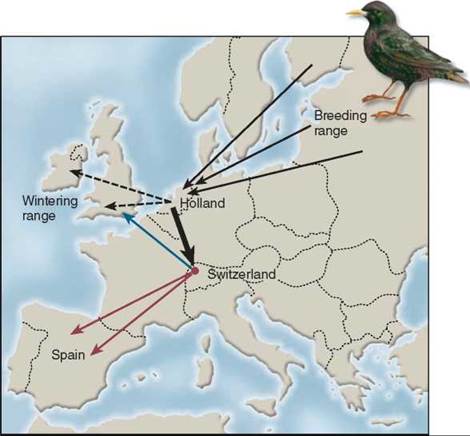

Biologists have studied migration with great interest. In attempting to understand how animals are able to navigate accurately over such long distances, it is important to understand the difference between compass sense (an innate ability to move in a particular direction, called “following a bearing”) and map sense (a learned ability to adjust a bearing depending on the animal’s location). Experiments on starlings shown in figure 37.10 indicate that inexperienced birds migrate using a compass sense, and older birds that have migrated previously also employ a map sense to help them navigate—in essence, they learn the route. Migrating birds were captured in Holland, the halfway point of their migration, and were taken to Switzerland where they were released. Inexperienced birds (the red arrows) kept flying in their original direction, while experienced birds (the blue arrow) were able to adjust course and reached their normal wintering grounds.

Figure 37.10. Starlings learn how to navigate.

The navigational abilities of inexperienced birds differ from those of adults that have made the migratory journey before. Starlings were captured in Holland, halfway along their full migratory route from Baltic breeding grounds to wintering grounds in the British Isles. These captured birds were transported to Switzerland and released. Experienced older birds compensated for the displacement and flew toward the normal wintering grounds (blue arrow). Inexperienced young birds kept flying in the same direction as before, on a course that took them toward Spain (red arrows).

The Compass Sense

In birds we now have a good understanding of how the compass sense is achieved. Many migrating birds have the ability to detect the earth’s magnetic field and to orient themselves with respect to it. In a closed indoor cage, they will attempt to move in the correct geographical direction, even though there are no visible external clues. However, the placement of a powerful magnet near the cage can alter the direction in which the birds attempt to move.

The first migration of young birds appears to be innately guided by the earth’s magnetic field. Inexperienced birds also use the sun and particularly the stars to orient themselves (migrating birds fly mainly at night).

The indigo bunting, which flies during the day and uses the sun to set its bearing, compensates for the movement of the sun in the sky as the day progresses by reference to the North Star, which does not move in the sky. Starlings compensate for the sun’s apparent movement in the sky by using an internal clock. If captive starlings are shown an experimental sun in a fixed position, they will change their orientation to it at a constant rate of about 15 degrees per hour—the same rate the sun moves across the sky.

The Map Sense

Much less is known about how migrating birds and other animals acquire their map sense. During their first migration, young birds move with a flock of experienced older birds that know the route, and during the course of the journey they appear to learn to recognize certain cues, such as the position of mountains and coastline.

Animals that migrate through featureless terrain present more of a puzzle. Consider the green sea turtle (figure 37.11). Every year great numbers of these large 400-pound turtles migrate with incredible precision from Brazil halfway across the Atlantic to Ascension Island, through 1,400 miles of open ocean, where females lay their eggs. Plowing head down through the waves, how do they find this tiny rocky island, over the horizon, more than a thousand miles away? No one knows for sure, although recent studies suggest that the direction of wave action provides an important navigational clue.

Figure 37.11. Examples of migration.

Key Learning Outcome 37.9. Many animals migrate in predictable ways, navigating by looking at the sun and stars, and in some cases by detecting magnetic fields. In many instances, young individuals learn the route by following experienced ones.