CHEMISTRY THE CENTRAL SCIENCE

2 ATOMS, MOLECULES, AND IONS

A COLLECTION OF UNCUT DIAMONDS. Diamond is one of the crystalline forms of carbon. Pure diamonds are clear and colorless. Small levels of impurities or defects cause diamond to have color—nitrogen produces yellow, whereas boron produces blue.

WHAT'S HEAD

2.1 THE ATOMIC THEORY OF MATTER

We begin with a brief history of the notion of atoms—the smallest pieces of matter.

2.2 THE DISCOVERY OF ATOMIC STRUCTURE

We then look at some key experiments that led to the discovery of electrons and to the nuclear model of the atom.

2.3 THE MODERN VIEW OF ATOMIC STRUCTURE

We explore the modern theory of atomic structure, including the ideas of atomic numbers, mass numbers, and isotopes.

2.4 ATOMIC WEIGHTS

We introduce the concept of atomic weights and how they relate to the masses of individual atoms.

2.5 THE PERIODIC TABLE

We examine the organization of the periodic table, in which elements are put in order of increasing atomic number and grouped by chemical similarity.

2.6 MOLECULES AND MOLECULAR COMPOUNDS

We discuss the assemblies of atoms called molecules and how their compositions are represented by empirical and molecular formulas.

2.7 IONS AND IONIC COMPOUNDS

We learn that atoms can gain or lose electrons to form ions. We also look at how to use the periodic table to predict the charges on ions and the empirical formulas of ionic compounds.

2.8 NAMING INORGANIC COMPOUNDS

We consider the systematic way in which substances are named, called nomenclature, and how this nomenclature is applied to inorganic compounds.

2.9 SOME SIMPLE ORGANIC COMPOUNDS

We introduce organic chemistry, the chemistry of the element carbon.

LOOK AROUND AT THE GREAT variety of colors, textures, and other properties in the materials that surround you—the colors in a garden, the texture of the fabric in your clothes, the solubility of sugar in a cup of coffee, or the transparency and beauty of a diamond. The materials in our world exhibit a striking and seemingly infinite variety of properties, but how do we understand and explain them? What makes diamonds transparent and hard, whereas table salt is brittle and dissolves in water? Why does paper burn, and why does water quench fires? The structure and behavior of atoms are key to understanding both the physical and chemical properties of matter.

Although the materials in our world vary greatly in their properties, everything is formed from only about 100 elements and, therefore, from only about 100 chemically different kinds of atoms. In a sense, the atoms are like the 26 letters of the English alphabet that join in different combinations to form the immense number of words in our language. But what rules govern the ways in which atoms combine? How do the properties of a substance relate to the kinds of atoms it contains? Indeed, what is an atom like, and what makes the atoms of one element different from those of another?

In this chapter we examine the basic structure of atoms and discuss the formation of molecules and ions, thereby providing a foundation for exploring chemistry more deeply in later chapters.

2.1 THE ATOMIC THEORY OF MATTER

Philosophers from the earliest times speculated about the nature of the fundamental “stuff” from which the world is made. Democritus (460–370 BC) and other early Greek philosophers described the material world as made up of tiny indivisible particles they called atomos, meaning “indivisible or uncuttable.” Later, however, Plato and Aristotle formulated the notion that there can be no ultimately indivisible particles, and the “atomic” view of matter faded for many centuries during which Aristotelean philosophy dominated Western culture.

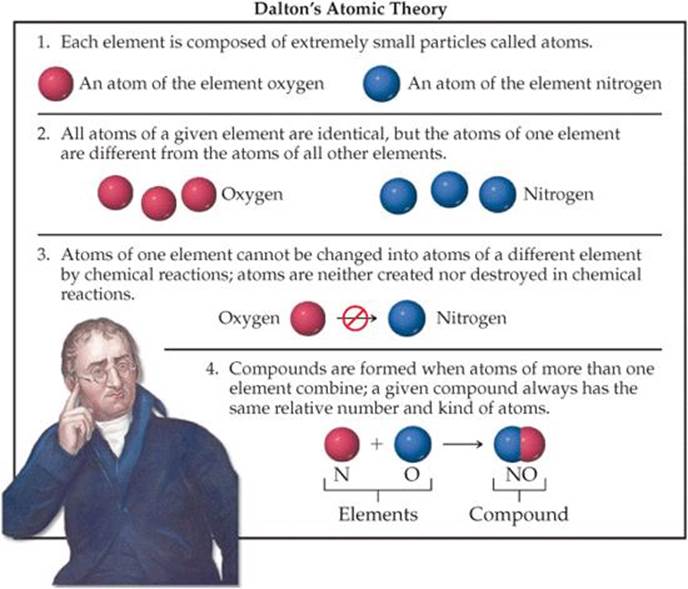

The notion of atoms reemerged in Europe during the seventeenth century. As chemists learned to measure the amounts of elements that reacted with one another to form new substances, the ground was laid for an atomic theory that linked the idea of elements with the idea of atoms. That theory came from the work of John Dalton during the period from 1803 to 1807. Dalton's atomic theory was based on the four postulates given in ![]() FIGURE 2.1.

FIGURE 2.1.

Dalton's theory explains several laws of chemical combination that were known during his time, including the law of constant composition ![]() (Section 1.2),* based on postulate 4:

(Section 1.2),* based on postulate 4:

In a given compound, the relative numbers and kinds of atoms are constant.

It also explains the law of conservation of mass, based on postulate 3:

The total mass of materials present after a chemical reaction is the same as the total mass present before the reaction.

A good theory explains known facts and predicts new ones. Dalton used his theory to deduce the law of multiple proportions:

If two elements A and B combine to form more than one compound, the masses of B that can combine with a given mass of A are in the ratio of small whole numbers.

![]() FIGURE 2.1 Dalton's atomic theory. John Dalton (1766–1844), the son of a poor English weaver, began teaching at age 12. He spent most of his years in Manchester, where he taught both grammar school and college. His lifelong interest in meteorology led him to study gases, then chemistry, and eventually atomic theory. Despite his humble beginnings, Dalton gained a strong scientific reputation during his lifetime.

FIGURE 2.1 Dalton's atomic theory. John Dalton (1766–1844), the son of a poor English weaver, began teaching at age 12. He spent most of his years in Manchester, where he taught both grammar school and college. His lifelong interest in meteorology led him to study gases, then chemistry, and eventually atomic theory. Despite his humble beginnings, Dalton gained a strong scientific reputation during his lifetime.

We can illustrate this law by considering water and hydrogen peroxide, both of which consist of the elements hydrogen and oxygen. In forming water, 8.0 g of oxygen combine with 1.0 g of hydrogen. In forming hydrogen peroxide, 16.0 g of oxygen combine with 1.0 g of hydrogen. Thus, the ratio of the mass of oxygen per gram of hydrogen in the two compounds is 2:1. Using Dalton's atomic theory, we conclude that hydrogen peroxide contains twice as many atoms of oxygen per hydrogen atom as does water.

![]() GIVE IT SOME THOUGHT

GIVE IT SOME THOUGHT

Compound A contains 1.333 g of oxygen per gram of carbon, whereas compound B contains 2.666 g of oxygen per gram of carbon.

a. What chemical law do these data illustrate?

b. If compound A has an equal number of oxygen and carbon atoms, what can we conclude about the composition of compound B?