5 Steps to a 5: AP European History 2024 - Bartolini-Salimbeni B., Petersen W., Arata K. 2023

STEP 4 Review the Knowledge You Need to Score High

9 Major Themes of Modern European History

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summary: The AP European History course is focused on seven broad themes. All of the questions on the AP European History Exam involve one or more of these themes. In this chapter you’ll learn more about the seven themes.

Key Idea:

The seven themes of the AP European History course and exam are as follows:

![]() Interaction of Europe and the World

Interaction of Europe and the World

![]() Economic and Commercial Developments

Economic and Commercial Developments

![]() Cultural and Intellectual Developments

Cultural and Intellectual Developments

![]() States and Other Institutions of Power

States and Other Institutions of Power

![]() Social Organization and Development

Social Organization and Development

![]() National and European Identity

National and European Identity

![]() Technological and Scientific Innovation

Technological and Scientific Innovation

Introduction

The AP European History Exam identifies six main themes in modern European history. These themes are explored throughout the curriculum of AP European history courses. In fact, all of the various kinds of questions posed on the AP European History Exam refer to one or more of these themes. The particulars of each theme will be discussed in detail in Chapters 11 through 25. For now, just become familiar with these broad themes, as such familiarity will allow you to take the first step in contextualizing the visual prompts from each question on the exam.

Interaction of Europe and the World

By the fifteenth century, increased wealth flowing into the economies of Western European kingdoms from reviving trade with Eastern civilizations made both the monarchies and the merchant class of Western Europe very wealthy. Beginning in the fifteenth century, the combined investment of those monarchies and merchant classes funded great voyages of exploration across the globe, establishing new trade routes and bringing European civilization into contact with civilizations previously unknown to Europeans. The effects of this exploration and interaction on both the civilization of Western Europe and on those they encountered were profound.

Economic and Commercial Developments

From the fifteenth through the nineteenth centuries, the economies of Western European civilization expanded and changed. The new wealth that flowed into those economies from their trading empires and colonies fostered a shift in the very nature of wealth and in who possessed it. At the outset of the fifteenth century, wealth was land, and it was literally in the hands of those who had the military ability to hold and protect it. Gradually, over the next four centuries, wealth became capital (money in all of its forms), whereas land became simply one form of capital—one more thing that could be bought and sold. The wealthy, those who had and controlled capital, became a larger and slightly more diverse segment of society, ranging from traditional landholders who were savvy enough to transform their traditional holdings into capital-producing concerns, to the class of merchants, bankers, and entrepreneurs who are often referred to as the bourgeoisie.

Cultural and Intellectual Developments

Throughout the course of modern European history, intellectuals were engaged in the pursuit of knowledge. In traditional or medieval European society, knowledge was produced by church scholars whose abilities to read and write allowed them access to ancient texts. From those texts, they chose information and a worldview that seemed compatible with Christian notions of revealed knowledge and a hierarchical order. Accordingly, traditional Christian scholars found knowledge in texts they believed to be divinely inspired and which presented a worldview in which humans sat in the middle (literally and figuratively) of a cosmos created especially for them by a loving God.

Beginning in the sixteenth century, increased wealth allowed European elites to create secular spaces for intellectual pursuits. This development bred a new type of secular scholar who stressed the use of observation and reason in the creation of knowledge, and who, in due course, successfully challenged the notion of a theocentric universe. This change resulted in a large variety of cultural responses.

States and Other Institutions of Power

Beginning in the fifteenth century, the expansion and increasing complexity of the European economy and a corresponding growth in the size of its populations put great stress upon the traditional social structures and institutions of European society. Changes in the means of production and exchange both fostered and benefitted from dramatic changes in where and how the population lived and worked.

Social Organization and Development

The economic and social changes occurring from the fifteenth through the twentieth centuries created demands for corresponding changes in the nature of the social hierarchy. Traditional European elites found themselves contending with newer, commercial elites for political power. The pre-industrial period saw women participating in sociocultural change. In the nineteenth century, women, along with industrial and urban workers began to agitate for access to, and sometimes participation in, the wielding of political power.

National and European Identity

The idea of national, and eventually European, identity was often based on shared language, geography, and political consolidation of power. The Reconquest of Spain, the creation of a parliamentary monarchy in England, the unification of Italy and Germany in the late nineteenth century are all examples of states united in their shared beliefs in social, political, cultural, and/or religious values. The idea of a European identity remains in flux, depending on changing economic, political, social, cultural, and legal frameworks.

Technological and Scientific Innovation

The twentieth century will be remembered as a century of wars—world wars, civil wars, wars of independence, and imperialism. What is especially interesting is the role of scientific and technological advances, and of the interactions between culture and science.

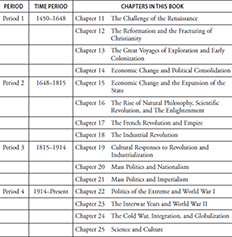

The Organization of the AP Course into Units

To organize the content relating to these major themes of European history, the College Board has defined four “units,” or time periods. These units form the basic structure of the AP course—but don’t worry, you won’t have to memorize these time periods. They are only a behind-the-scenes organizational structure for the course and won’t be part of the AP exam. It may be useful, however, to see what these four units are and to know how they correspond to the review chapters in this book, especially if, besides using this book, you are also using the College Board website to review for the AP exam. The table below provides this information.