Essential Writing Skills for College and Beyond (2014)

Part II. COMPOSING YOUR ESSAY

Chapter 7. Post-Research

YOUR IDEAS AND THEIR IDEAS

Now that you have read your research and understand it, how do you incorporate it into your essay?

Think of incorporation as your response to their ideas.

The scholars stated their opinions and evidence on the issue, and now you will state yours. Remember, as a writer of collegiate-level work, you are entering the academic conversation (The Great Debate). Now that you’ve read the scholars’ “cases” on the issue(s) you researched, you must address two key questions: Are you convinced by their argument and evidence? Why or why not? You will likely have one of three answers: Yes, No, or Maybe.

It is extremely important to address why you agree, disagree, or remain uncertain. If you agree, why? If you disagree, why? If you remain uncertain, why?

You’ll find on the following pages a discussion of each of these responses and how to verbalize them. However, the following rules of thumb will provide you with an overall guide for successfully incorporating the work of others into your essays.

RULES OF THUMB: INCORPORATING THE WORK OF OTHERS INTO YOUR ESSAY

1. IMMEDIATELY STATE YOUR OPINION OF THE SCHOLAR’S THEORY, IDEA, OR WORK. Do you agree (yes), disagree (no), or remain uncertain (maybe) about her major contention? Why?

2. DO NOT BE VAGUE ABOUT YOUR OPINION. Many students make the mistake of keeping the reader guessing or “saving” their evaluation of the research for “later.”

Academics don’t view vagueness as an invitation to keep reading; they see it as weak, inadequate writing. Academics expect authors to state their perspective immediately and spend the bulk of the essay defending and explaining that position.

3. ALWAYS EXPLAIN AND DEFEND YOUR POSITION, REGARDLESS OF YOUR STANCE. Whether you take a position of yes, no, or maybe, you must cite evidence to support and explain your stand.

YES: EXPRESSING AGREEMENT

Many students believe that agreeing with the scholars they cite will prove to be the easiest move, so this is indeed the position they take. They feel if they agree, they can simply state their agreement with the position or theory and move on. However, a simple statement of agreement does not constitute evaluation. Stating an opinion is only the first step in evaluation; once you determine your position on the issue, you must construct your defense of this opinion.

Examine the argument and its evidence closely; then, point out which specific elements prove its validity, establish its legitimacy, or point to its overall merit.

Remember, you don’t necessarily have to agree 100 percent with every idea or piece of evidence the scholar presents. Consider whether, overall, you find the scholar’s major point or argument valid, interesting, or insightful.

A Yes response to an author’s work may come in several forms:

· Complete, 100 percent agreement with the entirety of his work

· Overall agreement with most of the work

· Partial agreement with several major points within the work

These responses include the obvious Yes and also:

· Yes, but …

· Yes, except for …

· Yes, if …

· Yes, assuming …

· Yes, unless …

Don’t forget your “Because …”: Always state why you agree with the argument.

Some of the most prominent reasons for agreement with a scholar’s argument or perspective include the following. Cite these reasons, or add your own:

· Convincing argument

· Interesting, innovative argument

· Strong, substantial evidence to support the argument

· Accurately documented results and research

· Clearly organized

· Well-written work that illustrates the author’s expertise and depth of knowledge on the subject

· Excellent, impassioned use of language and rhetoric

Below you will find examples of ways to express your agreement with other scholars’ work and why you support their ideas.

|

YES: WHY |

SUGGESTED ACADEMIC TRANSLATION(S) |

|

“This scholar is brilliant!” |

· Jones discusses __________ in innovative, insightful ways that few other scholars have. Instead of __________, she __________. · Jones’s argument proves overwhelmingly convincing because __________. · The evidence Smith presents undoubtedly proves her point because __________. · Few readers will likely argue with Smith’s theory that __________ because she __________. |

|

“I agree with Wilson, but I also disagree with him.” |

· Wilson first argues__________, and indeed he is correct because __________. However, when he later states, __________, he misses the mark because __________. · Yes, Wilson’s finding of __________ is accurate; however, his presentation of __________ is not because __________. · Though Wilson makes an excellent point about __________, his evidence on __________ lacks credibility because __________. · Wilson’s argument of __________ stands up to scrutiny. He rightly points out __________, but then later on page _______, he states, “__________,” which illustrates that he fails to consider __________. |

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

New employees often think simply agreeing with the boss’s opinion is the way to ensure a promotion or raise. But this is not always the case. When you do agree with your boss, state why you agree and cite evidence that illustrates the validity of the perspective. Don’t be afraid to apply the No and Maybe strategies to your workplace conversations, too. Employees who illustrate their intelligence and capabilities are much more likely to garner raises and promotions than those who merely state their agreement with their supervisors’ ideas but never offer any of their own.

NO: EXPRESSING DISAGREEMENT

Many students worry about taking a position of disagreement with scholars because they think that if they disagree, their instructor may see this disagreement as haughtiness on the part of the student and punish them in the form of a low score. Remember, you’re not criticizing or evaluating the value of the scholar himself; you are evaluating the strength, merit, and significance of his work. You have every right—and responsibility—to state your opinion, including one of disagreement, if that is your honest perspective on the work.

This point is a good one to keep in mind as a writer, too; when your professors criticize your ideas, they are evaluating your work, not you. Your value as a student, as a person, is not in question. However, the value of your work is, and this point is true for the scholars whose work you examine.

Remember, you do not have to disagree 100 percent with every idea or piece of evidence the scholar presents. Consider whether, overall, you find the scholar’s major point or argument invalid, inaccurate, or illogical.

A No response to an author’s work may come in several forms:

· Complete 100 percent disagreement with the entirety of her work

· Overall disagreement with most of the work

· Disagreement with several major points within the work

Don’t forget your “Because …”: Always state why you disagree with the argument.

These responses include the obvious No and also:

· No, but …

· No, except for …

· No, unless …

· No, assuming …

· No, if …

Some of the most prominent reasons for disagreement with a scholar’s argument or perspective include the following. Cite these reasons, or add your own:

· Failure to present a convincing argument

· Boring, expected, trite, or hackneyed argument

· Weak, insubstantial evidence to support the argument

· Lack of or inaccurate documentation of the results

· Lack of or inaccurate citation of sources

· Lack of a central thesis and working structure

· Poorly written work that fails to illustrate the author’s expertise and depth of knowledge on the subject

· Unclear, confusing language and jargon employed throughout the work

Below you will find examples of ways to express your disagreement with other scholars’ work and why you oppose their ideas.

|

NO: WHY |

SUGGESTED ACADEMIC TRANSLATION(S) |

|

“No way. This is just stupid.” |

· The argument Smith presents fails logically because __________. · Smith’s argument remains unconvincing because __________. · The evidence Smith presents lacks credibility because __________. |

|

“Is this guy crazy? He’s contradicting himself.” |

· Brown first argues __________ ; however, he then argues __________. This contradiction shows his thinking on __________ is wrought with errors because __________. · Brown’s argument cannot be trusted; he vacillates on the issue of __________. He first states, “__________,” but then later, on page __________, he states, “__________.” |

|

“Really? He wrote a research paper about this? My ten-year-old sister knows that.” |

· Martin attempts to argue __________, but in fact __________ has been widely discussed by __________, __________, and __________. What Martin neglected to examine is __________. · Martin writes about __________ as though he presents to readers startling information, but, in fact, readers even vaguely familiar with __________ already understand __________. What Martin fails to discuss is the more important issue of __________. |

MAYBE: EXPRESSING UNCERTAINTY

Many students either forget about or purposefully avoid the Maybe response. Many professors will allow or even encourage students to take a Maybe position on an issue, as long as the student makes clear why she finds too much uncertainty surrounding a topic or issue to take a definitive stance.

However, taking a Maybe stance does not exempt you from presenting and evaluating evidence. In fact, the Maybe paper will likely argue two positions: the Yes and the No. If the essay’s position is Maybe, the writer will need to show why both Yes and No may be valid responses but in different areas or ways.

Please note the following cautions concerning Maybe:

1. Not all professors allow the Maybe paper; be sure to ask before taking the time to write it.

2. Taking a Maybe stance can be a bit boring for a reader. After all, you are not arguing Yes or No definitively; you are essentially shrugging your shoulders and saying the answer is not yet evident. This perspective is perfectly fine, and indeed it is possible to make it interesting, but just keep in mind that it can often be more of a challenge, especially for beginning writers, to make the Maybe response as interesting as a direct Yes or No.

If after reading these cautions you are not deterred from your Maybe stance, then by all means, proceed. Maybe is an important answer, especially within the philosophy and medical fields.

A Maybe response to an author’s work may come in several forms:

· Agreement with one aspect of her argument or analysis but disagreement with her overall conclusions or thesis

· Agreement with most of the argument itself but concern over the validity or accuracy of the evidence presented

Don’t forget your “Because …”: Always state the reasons for your uncertainty with the scholar’s argument and/or evidence.

Some of the most prominent reasons for uncertainty regarding a scholar’s argument or perspective include the following. Cite these reasons, or add your own:

· Convincing argument presented but the writer needs to cite more evidence to support it

· Interesting argument presented but the validity and credibility of the evidence cited remains in question

· Inadequate documentation of results or evidence

· Central thesis with interesting points but much of the work is confusing and difficult to understand or follow

Below you will find some of students’ most common Maybe reactions to the research they encounter and suggestions about how to formalize and specify your opinion for your essay.

|

MAYBE: WHY |

SUGGESTED ACADEMIC TRANSLATION(S) |

|

“Well, yeah, I’d agree with that if …” |

· Cohen’s point may be valid; however, __________. · Although Cohen rightly points out __________, his overall argument of __________ fails to convince because _______________. · Cohen’s argument about __________, though interesting, remains unconvincing overall because he fails to address __________. |

|

“This article started out interesting, but then it got weird and confusing.” |

· The first few pages of Smith’s article prove interesting and insightful in that she illustrates __________. However, as the article progresses, her discussion on __________ seems to veer off topic because she __________. · Although Smith had a valid point about __________, she quickly lost credibility on page __________ as she began to discuss __________. |

|

“I disagree with almost everything she wrote, but at the end she finally says something right!” |

· It’s difficult to take a clear stand on Smith’s work. Her argument on __________ proves invalid because __________. However, near the end of the article, she points out __________, and her evidence of __________ is indeed convincing. |

SELECTING RELEVANT QUOTES

Once students find and formulate a response to scholarly sources, they often have trouble selecting quotes from within those sources. With such long articles or entire books looming before them, they wonder how they will choose particular sentences to insert into their paper.

Only quote what you can explain and defend.

In other words, always have a reason for why you chose the particular quote(s) you cite.

DEFENDING AND SELECTING YOUR QUOTES

Tie all quotes directly and clearly to your claim, and always explain each quote’s significance. Never assume your reader understands the quote’s significance or that its relevance “speaks for itself.” Usually it does not.

Remember, the key to selecting quotes is relevance. Always have a justification for your inclusion of any quote(s). Ask and answer the following questions:

1. How is this quote relevant to your discussion?

2. Why does it go in the precise position in which you placed it in your paper?

Your answers to these questions will form the “E” (Explanation) section of your essay. It may help to review the sections on “I” and “E” in chapter 3.

PARAPHRASING VS. QUOTING

Paraphrasing sources allows more of your thinking to come through. Remember, your readers are seeking your words, not someone else’s. Don’t bury your ideas beneath a heap of quotations. Instead, use quotations to support and prove your point.

You should quote:

· When a character or writer’s specific language or phrasing matter

· When language is particularly eloquent, impassioned, or significant

In other words, quote when the specific wording or phrasing is significant.

You should paraphrase:

· When referring to an overall point or assertion of a text

· When referring to a specific event in the text

In other words, paraphrase when the specific wording or phrasing is not necessarily significant but the overall summary or point is.

Study Russell’s example below, which demonstrates the debate of whether to paraphrase or quote.

William Buckley points out “the reasons we don’t complain” (201).

In this example, Russell unnecessarily included a direct quote. He may simply refer to the text’s major point or claim, which in this case seems to be reasons people do not complain. However, what are these reasons? Do the particular reasons matter, or is Russell merely pointing out that Buckley raises the issue? He must explain the significance of this point and why Buckley raises it in his paper.

See Russell’s rewrite below.

William Buckley points to the various reasons we do not complain—such as fear of others’ reactions and sheer laziness—to make a larger point about overall American complacency and its connection to wide-scale injustice within our society.

Russell decided to paraphrase rather than use a direct quote, which seems appropriate given that he largely summarizes Buckley’s overall argument. He clearly feels the larger point of Buckley’s essay was more important than any single phrasing he used. Russell has also done a nice job of pointing out Buckley’s “So what?” which is that Americans’ failure to complain has led to injustices in our society. However, Russell now must tie Buckley’s point to his own.

William Buckley points to the various reasons we do not complain—such as fear of others’ reactions or sheer laziness—to make a larger point about overall American complacency and its connection to wide-scale injustice within our society. Indeed, Buckley has a point worth noting in terms of considering the low wages of tipped employees and the failure of restaurant workers to complain about their unfair, unethical treatment by powerful restaurant chains and their lobbyists.

There is not necessarily a right or wrong answer when determining whether to use direct quotes or paraphrases. Another student may have elected to quote Buckley directly, and this decision would be fine, as long as she explained the quote’s significance to her own ideas.

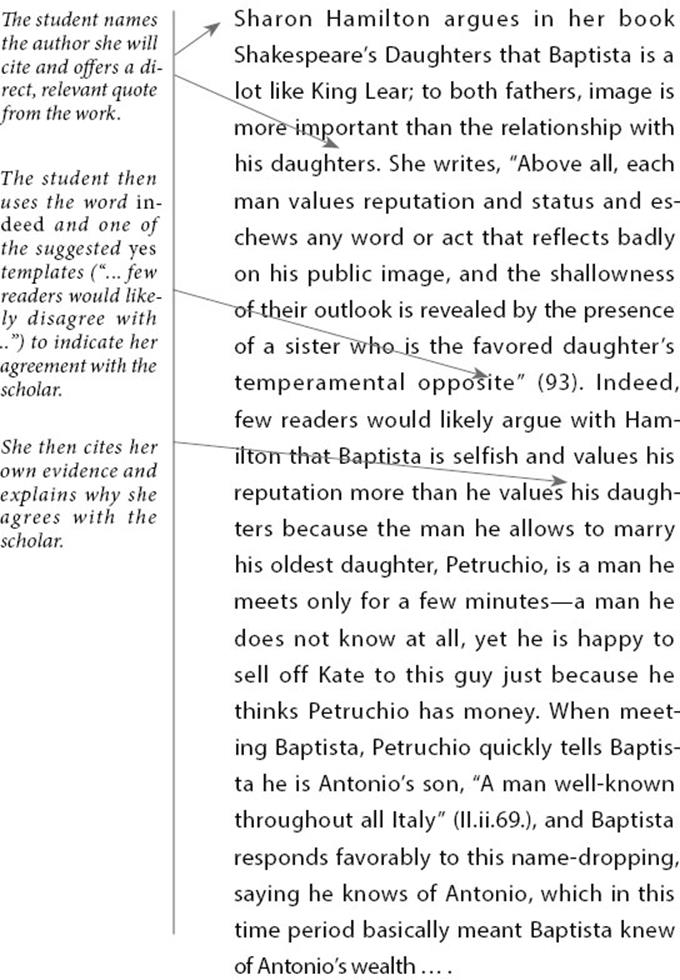

INCORPORATE THEIR IDEAS INTO YOURS: YES

The example below is taken from a student’s paragraph in which she agrees with the scholar’s work she cites. See the notes in the margin for commentary on the student’s work.

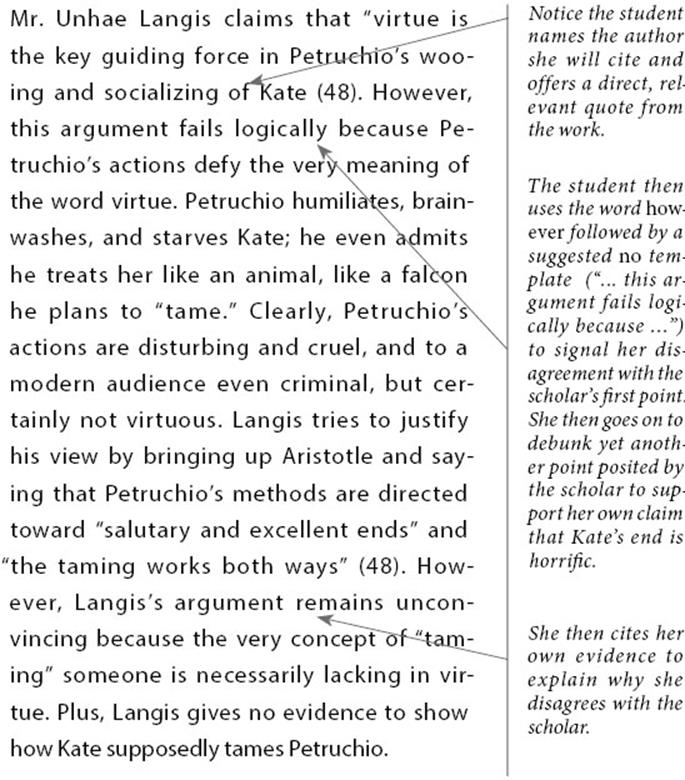

INCORPORATE THEIR IDEAS INTO YOURS: NO

This example is taken from a student’s paragraph in which she disagrees with the scholar whose work she cites.

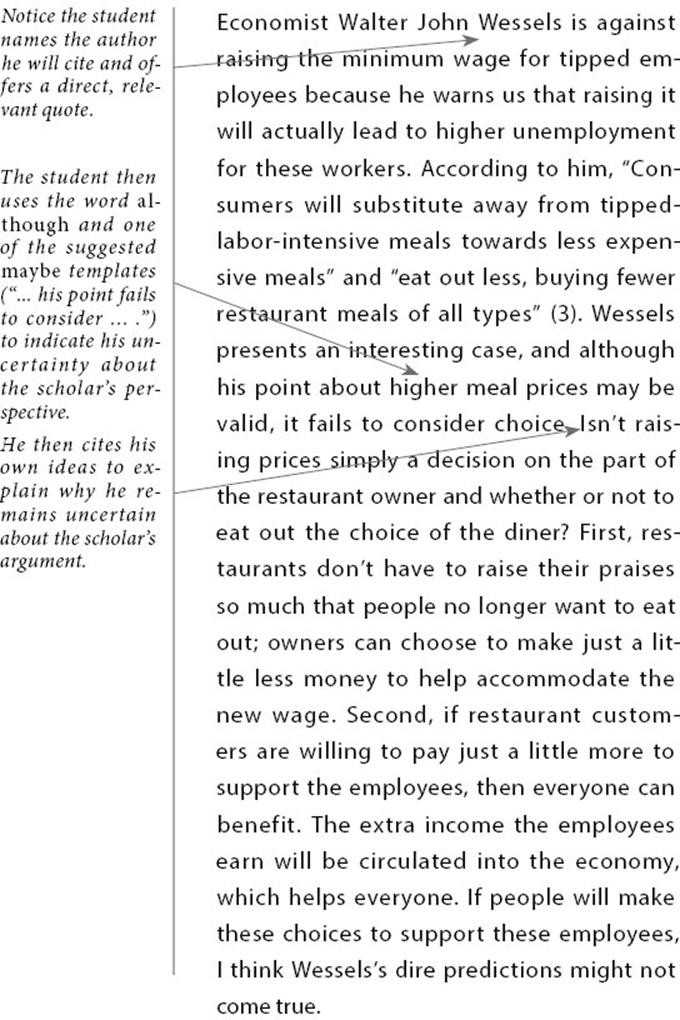

INCORPORATE THEIR IDEAS INTO YOURS: MAYBE

CITING THEIR IDEAS

Once you have found, evaluated, and incorporated your sources, you must cite them. Academic essays require writers to cite sources in two ways:

· In-text or parenthetical citations

· Works Cited or Reference page

You will find further discussion of how to cite parenthetically and create a Works Cited page later in this chapter. However, before you start the citation process, be sure you know which citation form or style your instructor requires. Your prompt sheet should include directions that dictate which style to use; if not, make sure you ask!

Below you will find the three most common types of citation forms and the disciplines that typically use them:

• MLA (MODERN LANGUAGE ASSOCIATION): The Humanities

• Language and Literature

• Gender and Cultural Studies

• Art History

• Film and Television Studies (may also use Chicago style, so ask)

• Advertising

• Philosophy (may also use Chicago style, so ask)

• APA (AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION): Social and Behavioral Sciences

• Psychology and Sociology

• Education

• Linguistics

• Business and Economics

• Nursing

• CHICAGO STYLE (CHICAGO MANUAL OF STYLE)

• History (may also use MLA or APA, so ask)

• Information Science

• Philosophy (may also use MLA style, so ask)

• Communications and Journalism

• Film and Television Studies (may also use MLA or APA, so ask)

CREATING IN-TEXT OR PARENTHETICAL CITATIONS

The parenthetical or in-text citation is exactly what it sounds like: a citation writers insert into the actual text of their essay inside parentheses.

Remember, each reference or source you cite in your essay must appear in the References or Works Cited page.

To ensure you properly cite sources within the text of your essay, follow these steps:

1. CITE THE SOURCE AS YOU USE IT—IN THE BODY OF THE ESSAY. Usually this citation involves simply writing the author’s last name and the page number inside the parentheses. However, some sources (especially Web sources) are more difficult to cite, so be sure to consult the proper style manual or website (MLA, APA, or Chicago, etc.) for examples on how to cite properly.

2. BE SURE ALL SOURCES CITED IN YOUR ESSAY GAIN A LISTING ON YOUR WORKS CITED PAGE. After you cite your sources in the text, you will create a page at the end of your document that lists all the sources you cited in the essay’s body. (For details on how to create this document, see later in this chapter.)

TO CITE OR NOT TO CITE …

This is indeed the question for many students; they wonder whether they should cite every source they found during research. The rule of thumb is to cite a source’s work anytime you reference, mention, or in any way use or consult it.

Do not fear overciting. If you are uncertain about whether to cite, go ahead and cite the source to be safe. If you cite it but you did not need to, you might lose a few points, but you won’t risk charges of plagiarism—a serious academic offense. (For more info on plagiarism, see chapter 10.)

When in doubt, cite. It’s better to cite unnecessarily than to omit the citation when you needed it.

If you found a source while researching but did not use it within your essay, you do not need to cite it. However, if your ideas in any way are based on that scholar’s work, then you need to cite it.

Study the following brief examples to gain an overview of in-text or parenthetical citations in the two most common styles: MLA and APA. For further examples, see the appropriate style manual (MLA, APA, or Chicago) or visit your college or university library’s web page; most offer comprehensive citation guides.

EXAMPLE 1: MLA

INCORRECT: In her book Shakespeare’s Daughters, Sharon Hamilton claims, “Nowhere is Shakespeare more astute than in his portrayal of fathers and daughters and the factors that foster or undermine that bond” (Hamilton p. 2).

Since the student already mentioned the author’s name, she does not need to include it inside the parenthetical citation. She also doesn’t need to include the “p.” for MLA citation style; she should only provide the actual page number.

CORRECT: In her book Shakespeare’s Daughters, Sharon Hamilton claims, “Nowhere is Shakespeare more astute than in his portrayal of fathers and daughters and the factors that foster or undermine that bond” (2).

EXAMPLE 2: APA

INCORRECT: According to Cooper and Hall, raising the minimum wage would provide a “modest stimulus to the entire economy, as increased wages would lead to increased consumer spending, which would contribute to GDP growth and modest employment gains” (Cooper & Hall, 2).

The student already listed the authors’ names, so he does not need to include them again inside the parentheses. He also must cite the date of the publication and insert p. with the page number reference to adhere to APA rules.

CORRECT: According to Cooper and Hall (2013), raising the minimum wage would provide a “modest stimulus to the entire economy, as increased wages would lead to increased consumer spending, which would contribute to GDP growth and modest employment gains” (p. 2).

CREATING A WORKS CITED OR REFERENCES PAGE

The parenthetical references you cite within the body of your text refer your reader to the final page of your document: In other words, it gives the reader a list of all sources referenced within the essay. We call this list a Works Cited or References page. All serious scholars must include such a page to prove they used the work of experts to support and create their own. You, too, must include such a page if you cite, consult, or in any way use or reference the work of others.

Remember the Golden Rule for creating the Works Cited page: Ensure your list adheres to the style of the discipline for which you are writing (MLA style for English, APA style for psychology, Chicago style for communication, etc).

Most libraries offer citation functions that will format your sources into the appropriate citation style, so it is probably not necessary for you to spend hours poring over a style manual.

To use the citation feature:

1. Click on the book or article’s title from the listing within the database.

2. Scan the page for the citation function; look for the word cite or citation; usually you’ll find it on the right-hand side of the screen.

3. Click on this icon, and select your citation style (MLA, APA, or Chicago). Copy and paste the citation, and insert it into your essay’s Works Cited or Reference page.

Even with these handy citation functions, you will need to have general knowledge of the style’s rules so you can check the work of the computer’s citation functions. Few citation functions actually cite sources 100 percent accurately, so always check their work before you submit your essay. It also helps to use only your college or university’s library—not Internet-based citation functions.

CITATION FORMULAS FOR WORKS CITED OR REFERENCES PAGES

Whether you title your final page “Works Cited” or “References” will depend on the discipline for which you write. Academics typically use the term “Works Cited” when citing sources with MLA format, whereas we use “References” when citing sources using APA format. When in doubt, ask your instructor which term she prefers. For format formulas and examples, see below and on the following pages.

MLA FORMULAS

BOOK (WITH ONLY ONE AUTHOR)

Author’s Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. City of Publication: Publisher, Year of Publication. Format.

ESSAY OR CHAPTER FROM AN EDITED BOOK

Author’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Essay or Chapter.” Title of Edited Book. Ed. Editor First Name Last Name. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of Publication. Pages of Essay or chapter. Format.

ARTICLE IN A SCHOLARLY JOURNAL

Author’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal Volume. Number (Year of Publication): Page Numbers. Format.

APA FORMULAS

BOOK (WITH ONLY ONE AUTHOR)

Author Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Date of publication). Book Title. City, STATE of Publication: Publisher.

ARTICLE IN JOURNAL WITH A DIGITAL OBJECT IDENTIFIER (DOI)

Author Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Year of Publication). Title of Article. Journal Title, Volume, Article Page Numbers. doi: number

ARTICLE IN JOURNAL WITHOUT DOI (WHEN DOI IS NOT AVAILABLE)

Author Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Year of Publication). Title of Article. Journal Title, Volume (Issue Number), Article Page Number. Retrieved from URL address

EXAMPLES

Once you’ve collected your list of citations, consult the appropriate handbook to ensure the citation style is correct. Look specifically for proper indentation on the second line of each entry—many Web citation generators leave out this indention.

EXAMPLE 1: MLA

INCORRECT:

Hamilton, Sharon. Shakespeare’s Daughters. Jefferson, N. C.: McFarland, 2003. Print.

Langis, Unhae. Marriage, The Violent Traverse From Two To One In The Taming Of The Shrew And Othello. Journal Of The Wooden O Symposium 8 (2008): 45–63.

The student should double space within and between each entry, ensure it is alphabetized, and indent all subsequent lines of entries by 0.5 inches from the left margin. These are all required rules of MLA citation. In the second entry, the student must place quotation marks around the article title and italicize the title of the journal. She must also indicate the medium of the article (print or Web), and, if she accessed it online, the database from which she accessed it and the date.

CORRECT:

Hamilton, Sharon. Shakespeare’s Daughters. Jefferson, N. C.: McFarland, 2003. Print.

Langis, Unhae. “Marriage, The Violent Traverse From Two To One In The Taming Of The Shrew And Othello.” Journal Of The Wooden O Symposium 8 (2008): 45–63. Academic Search Complete. Web. 2 February 2014.

EXAMPLE 2: APA

INCORRECT:

Wessels, W. (1993). “The minimum wage and tipped employees.” Journal of Labor Research, 14(3), 213–226.

Belman, Dale and Paul Wolfson. “The Effect of Legislated Minimum Wage Increases on Employment and Hours: A Dynamic Analysis.” LABOUR: Review of Labour Economics and Industrial Relations, 24 (1), 1–25. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9914.2010.00468.x

The student should alphabetize the entries by author’s last names and use only the initials of the authors’ first and middle names (do not spell out the first or middle names in APA style). He should place double spaces between each element of the citation. He should also remove the quotation marks around the titles of the articles and capitalize only the first letter of the first word in the title and subtitle. APA citation does not require quotation marks to indicate titles. (MLA, however, does.)

CORRECT:

Belman, D. L., & Wolfson, P. (2010). The effect of legislated minimum wage increases on employment and hours: A dynamic analysis. LABOUR: Review of Labour Economics and Industrial Relations, 24 (1), 1–25. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9914.2010.00468.x

Wessels, W. (1993). The minimum wage and tipped employees. Journal of Labor Research, 14 (3), 213–226.