Literary articles - Lewis Carroll 2025

Malice in Wonderland: The Elegy of Receding Childhood

“It's no use going back yesterday, because I was a different person back then” the words of a confused seven-year-old protagonist of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass hold a far deeper meaning: the price of growing up and leaving childhood behind. In the story, all Little Alice ever wanted was to be treated as a grown up, if it is her choice, then why does her voice have such an elegiac tone?

In the golden afternoon when Alice ventures ‘Down the rabbit Hole' and eventually ‘Through the Looking Glass' Alice finds herself in a fantastic land amongst talking flowers and animals in the Kingdom of Cards and Chess. In the cinematic journey of Wonderland, filled with ‘nonsense' repartees and deceivingly simple wits, we find ourselves stumbling upon certain symbols and themes that cannot be labelled off as simply childish or nonsensical. From the very beginning Carroll's idyllic world of innocence is seen at the verge of decay, as it is perpetually torn in the dilemma “To grow up or not to grow up”. The protagonist, frustrated of her subordinate position in an adult's world must go any length to make herself ‘grow'; whether it be eating “EAT ME” cake to give her a literal phallic growth, acting out of the penis-envy[Tenniel's illustrations (pg 13)] or going through the politically endangered red-and-white (almost blood-and-bandage) coloured Chess board World, to become the Queen; even threatening the idyllic inhabitants of Wonderland with a Darwinian reminder of her position in the Food-Chain hierarchy. This struggle to attain adult maturity is underlined with a certain darkness of elegy from the Narrator's part as a reminder that there will come a time when the ‘Sweet Summer Child' will exist no more.

The aim of my paper is to assess how Lewis Carroll deals with the loss of childhood and innocence in both Alice and her Wonderland, and how the elegiac mode resulting from the loss affects the narrative.

“The shadow of a sigh

May tremble through the story,

For “happy summer days” gone by,

And vanish'd summer glory–“

--Lewis Carroll, Prologue of Through the Looking Glass

For centuries, Lewis Carroll's Alice is adored by the reading community for her fantastic journey in Wonderland. For centuries Alice and her Wonderland has been the subject of literary criticism for its presentation, re-presentation, subversion and exaggeration of the real life aspects of Victorian England. However, reading upon some critical theories and opinions, I have observed that this children's fantasy that daringly ventures through the rabbit hole and the looking glass into the cinematographic lands of anthropomorphic fauna and flora and objects, conceals a subtle elegiac darkness beneath its innocent landscape. The aim of this paper will be to unveil, to decode and to decipher those subversive elements of the story, and how, after deciphering those, the ever-young central Protagonist of the text: Alice will not be looked upon as a typical Victorian Child anymore.

I will attempt to justify my opinions in consecutively four main themes. Firstly I will address how Alice attempts ascend to her sexual growth; secondly I will enumerate how the self of the author and his fictional identity slowly merges into one with the said theme; thirdly I will address some existential problems of the inhabitants of Wonderland and their conflict with the protagonist ; fourthly I will address how despite the political and legal obstruction to confine Alice's childhood, she slowly fades away from her innocence, resulting the tonal bleakness in the entire narrative meant for an innocent child.

Rabbit Hole and Looking Glass: The Problematic Female

The very starting point of the story, the ‘Fall' down the rabbit hole, denotes that it is not a simple-minded fairytale that is all marvellous. The ‘Fall' takes place because Alice (either consciously or unwittingly) escapes the ‘Reality' that was constructed by strict, compartmentalised binaries by adults: what is true, what can be true, and what is not true. If we are to observe Alice in chapter I of Alice in Wonderland , she is seen reading a book but she is not attentive. The Book in Alice's that confirms her place in the Privileged class of Victorian society also becomes symbol of subordination: no matter what she does or achieves, she can never exceed her father, Mr. Liddell, who was the Dean of Christ Church College, Oxford [i] . In the first two lines, the author establishes a world that was serene yet mundane and in times, exasperating, which is a brilliant contrast against the world she fell, which was completely immersed in the schizoid element of depth [ii] .

And how she can into that world? By following a white Rabbit, which to critic Florence Becker Lennon “is a birth dream indeed-and what a symbol-a white rabbit for fertility!” [iii] Thus the process of entering and adjusting in Wonderland is filled with suggestive images. This is the world that welcomes Alice as a sexually dominating entity. Her exploring the ‘dark hall' and finding a ‘little door' is a clear image of the vaginal passage, which is carefully found by Alice by turning the very symbolic curtain of the labia [iv] . The sexual images, in times, merges with the ones as sublime as a rigorous creative process. The little door that showed ‘beds of bright flowers' and ‘cool fountain' into the other world, is the passage to an Edenic world, it is a world where she can symbolically explore her own crevices of sexual-intellectual-creative-credo which the conventional Victorian society would not allow her; she can even be as ambitious as to control the norms (if Wonderland is at all ‘Her' world in the strictest sense) of the place, which again, reality would not let her have it in her own way. This world is, till now, entirely on her whims like that of a patriarchal authority. It offers her to satiate her appetite with the very suggestive drink and cake ‘EAT ME' and ‘DRINK ME'. The bottle of “DRINK ME” having a mixed flavour of “cherry tart, custard, pine-apple, roast turkey, toffy and hot buttered toast”; presents an edible landscape that is very gluttonously satisfying. The cake ‘EAT ME' in this context becomes more suggestive than the drink, for as soon as she finishes the cake, she starts to grow. The growing process of Alice is very phallic [v] , and in a very Jungian sense, she is now in touch with her ‘Masculine' self: the ‘Animus'. [vi]

The sexual identity of Alice is surprisingly dual: she is both Alice the penetrator and Alice the Conceiver. After her state of very Phallic Growth, Alice plays the role of an internal object. She floods the ‘little' room in her own symbolic “pool of tears” that so suggestively indicate at amniotic fluids; it is the very pregnant state of Alice's mind which anticipates her journey in the next realm. In a deeper sense, the Pool of Tears can also be likened with that of River Lethe, where souls of the dead are washed off their past life to be reborn. This very pregnant creative process is soon parodied by Alice expelling the lizard violently from that room, which had been observed by Deleuze as “the schizoid sequence of child-penis-excrement” [vii] .In all these prevailing images, we see Alice embodying the state of the Victorian Female: She is this supine, helpless and procreating body that has no function other than to subjugate to her male masters. It is quite prominent when the Rabbit,

Fig 1: “Alice turning the curtain to reveal the tiny door to Wonderland” by Sir John Tenniel

presumably a male figure mistakes her as his housemaid ‘Mary Ann' and orders her to fetch off her gloves.

First, the narrator refers to Alice´s character formation as rather strange “for this curious child was very fond of pretending to be two people”. So, it is implied that her person is ambivalent but the question arises why is it so? There may be more reasons why Alice is presented as having her identity in fragmentation. She is represented as a phallic figure but she is deprived of a phallus, while in the other hand, she steadfastly tries to operate her Victorian Rationality but her body becomes problematic.

“curious and curiouser!” cried Alice (she was so much surprised, that for the moment she quiet forgot how to speak good English). “Now I'm opening out like the largest telescope that ever was! Good-bye feet!” (For when she looked down at her feet, they seemed to be almost out of sight, they were getting so far off) [viii]

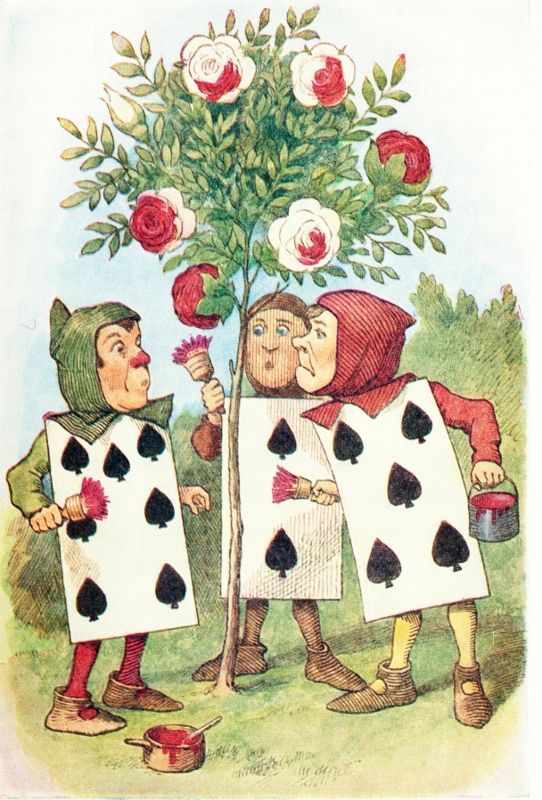

As a result, Alice is not at first able to become the whole entity because she is simultaneously acting according to these environments which constitute her identity, and therefore she finds herself caught somewhere between them and is bound to search for the way to settle this problem: “But if I´m not the same, the next question is, Who in the world am I?” That is, Alice´s self is seriously affected by her fall to the Wonderland and she is bound to cope with this dramatic change. This is a serious question for self identity-she has fallen from the conscious world in the depth of unconscious, and from the conflict between the conscious world Alice and Alice influenced by the predominance of the unconscious, there is a hope of new identity. If we are to translate the previous sexual imageries of a little girl suddenly becoming symbolic to sexual potency, Alice in her own identity crises is now an adolescent girl, who is unsure about her sudden changes in body and sexuality and eventually irritable and confused about the world around her. Soon the place becomes something which is at all not meant for child, when Alice reaches the Croquet Garden of the queen. The Card-Gardeners, who are so preoccupied to paint the white roses red, not only mar the natural beauty of the rose, but symbolically do something even grimmer. The White rose, which has always been symbolic of purity and virginity, associated with feminine innocence is being forcefully being coloured red: the typical symbol of a girl starting her menstrual cycle. However, the menstrual cycle is brought upon forcefully, unnaturally, which Haughton agrees with all the analyses that they provide in that level are that “a child's view of adulthood... dismayingly bizarre and perverse.” [ix]

Upon her first arrival in the wonderland, Alice is portrayed as someone that of a Green-serpent like figure in the supposedly utopic, idyllic, Edenic wonderland. In the fifth chapter of ‘Alice in Wonderland', her phallic-like length of her neck has gone alarmingly “an immense length” that her head is above the trees. The alarm of the grotesque is subverted when Alice is “delighted to find that her neck would bend about easily in any direction, like a serpent.” However, the grotesque soon resurfaces with viewpoint of the Pigeon's anxiety: “I suppose you'll be telling me next that you never tasted an egg!” The jokes that follow pick up and make explicit the dark meaning of the narrator quietly suggestive simile:

“I have tasted eggs, certainly”, said Alice, who was a very truthful child; “but little girls eat eggs quite as much as serpents do, you know.”

“I don't believe it,” said the pigeon; “but if they do, why, they they're a kind of serpent: that's all I can say” [x]

Alice, the girl-child, is identified as the symbol of corruption and decay in wonderland: a misogynistic figure, like that of Eve. Her entrance is seen as a threat to the inhabitants of Wonderland.

Fig 2: “Now I'm opening out like the largest telescope that ever was!” by Sir John Tenniel

By the time Alice is in the ‘Looking Glass' story, she is no longer (metaphorically) a child [xi] . The Looking glass, which has been an inseparable entity of a woman's domain, becomes a medium to look at the reality of the adult world which is coarser and more violent. In a tonally bleaker, more elegiac Through the Looking Glass, the winter sequel to the Maytime trip to Wonderland, Alice's sense of self hardens in the colder, more political climate she finds six months later behind the glass. The looking glass, like Keats' ‘magic casement' leads into the world of Victorian Mediism and the ‘dark wood' of Spenserian Romance, albeit in a comically warped form. Even the garden of live flowers offers a pricklier, colder pastoral that that of Wonderland, as can be seen in the less that rosy world view of the Rose Alice chats to:

“You're beginning to fade, you know-and then one ca'n't help one's petals getting a little untidy.”

Alice didn't like this idea at all: so to change the subject, she asked “Does she ever come out here?”

“I daresay you'll see her soon,” said the Rose. “She's one of the kind that has nine spikes, you know”

“Where does she wear them?” Alice asked with some curiosity.

“Why all round her head, of course,” the Rose replied. “I was wondering you hadn't got some too. I thought it was the regular rule.” [xii]

Against the cruel pathos of seeing Alice as a fading flower, symbolic of her fading childhood, the Rose presents adulthood with a certain grim realism.

“If you knew Time as well as I do... [it's not] it, it's Him ”: the narrator exposed?

In the previous part I have discussed some strong themes of problematic female sexuality, and now the question may be raised, why they are actually there, when it was originally meant for Victorian children to read. It has been long debated that the poignant female sexuality in Alice's journey is the psychological reflexion of the Narrator's own sexual identity and that of his little ‘girl-friends', which sometimes involve itself with Time and Death. This is expressed in the anxiety emerging from the conflict of fear of growing up and belated sexual development.

The unique concept of time in Alice's Wonderland may be due to Carroll's own experiences with the premonitory stage of migraine headache. Carroll being one of the most noted historical sufferers of migraine, as physician Fredrick Speer notes, influences greatly Alice's experiences with Carroll's “Lilliputian” and “Brobdingnagian” [xiii] experienced with timeline, conceived under migraine prodrome or aura. However, literary critics such as Calvin R. Peterson do not take this explanation at face value. In this paper too, the physicist's view cannot fully be supported as it only depicts the fast-paced and the sloth-like advancement of time, but not with Carroll's obsession (in several cases) a ‘Time out of Time'.

[xiv] From an early age, he was interested in time and wrote several journal on this subject “where does the day begin?” he always seems to have been battling himself with time, attempting to avoid being caught by time or trying to entrap time himself. This obsession influences the unique concept of ‘Time out of Time' in Alice. The rabbit's watch suggests Chronos, to whose timeline Alice followed the rabbit hole. From that moment the narrator isolated the reader (and Alice conveniently) from the historical determinism to the world of topsy-turvy world of Saturnian level. This world takes place, as Carroll suggests in the prologue “All in the golden afternoon ... with little skill, By little arms are plied,” [xv] With this suggestion, and that of Alice's turning the golden Key to open the door to Wonderland, we are led to a pre-utopian world, in which the Great Titan of Time Chronos rules. By the time Alice reaches the Mad Hatter's tea-party, she finds herself in a space where time is nonexistent

Fig 3: “Alice the ‘Serpent' and Pigeon”, From The original manuscript of the story, titled ‘ Alice's Adventure Underground ', handwritten and illustrated by Carroll and presented to Alice Pleasance Liddell as a Christmas present, at 1864. (Credit: Harvard University Library)

Fig 4: Coloured version of John Tenniel "The Queen's Croquet Ground" - Gardeners painting (The Annoted Alice, 1956)

Fig 5: Edited image of Alice Pleasance Liddell (18 years), and “Queen Alice” (sketch) by Sir John Tenniel. (credit: http://still-she-haunts-me-phantomwise.tumblr.com/page/353)

“What day of the month is it?” he said, turning to Alice: he had taken his watch out of his pocket, and was looking at it uneasily, shaking it every now and then, and holding it to his ear.

Alice considered a little, and said, “The fourth.”

“Two days wrong!” sighed the Hatter. “I told you butter wouldn't't suit the works!” he added, looking angrily at the March Hare.

...

Alice had been looking over his shoulder with some curiosity. “What a funny watch!” she remarked. “It tells the day of the month, and doesn't tell what o'clock it is!”

“Why should it?” muttered the Hatter. “Does your watch tell you what year it is?”

“Of course not,” Alice replied very readily: “but that's because it stays the same year for such a long time together.”

“Which is just the case with mine,” said the Hatter

It seemed to Alice a positively queer thing that it is at all possible to ‘Murder' time, as the Mad-Hatter claimed. It is only possible when we see the Narrator himself as personified time, with whom the chronological harmony exists in the meta-narrative of Wonderland. The desperately stopped-in-time Mad Tea Party can be seen as the Narrator's obsession with capturing the perfect moment. Carroll of course had a hobby of photography, a fashionable pastime in Victorian era, the perfect symbiosis between science and art that had appealed to his fertile imagination. Lebailly finds in his essay ‘C.L. Dodgeson's and the Victorian Cult of Child' (1998) that Carroll's artistic and emotional “obsession” with ‘child-females' had merged with his photographing hobby which will allow his ‘child friends' to remain forever young.

The White Knight, who helplessly stumbles around can be viewed as Carroll's ultimate incarnation in the ‘Alice' stories. The White Knight, like the narrator-is an inventor of gadgets, puzzles, riddles, games and conundrums. Unlike the Knave of Heart, who was in the truest sense the ‘Knave' (for committing a crime as serious as stealing the Queen of Heart's Tarts), the White Knight is innocent of any crime, muddled and awkward. In his tendency to fall upside down, he seems to be a chronic partial self to the Cheshire cat in Wonderland-embodiment of the detached intellectualism: “what does it matter where my body happens to be? My mind goes on working the same, in fact the more head downward I am, the more I keep inventing new things”. This particular crank inventor in the White Knight is the mirror image of Carroll who was a habitual mental researcher, detached from the outer world, the “still” man as Mark Twain defines him. [xvi] In spite of his Imaginative temper and childish innocence, he is not free of guilt. He is guilty of the typical narcissistic practice of the adults imposing their opinion on the child: in his case, he attempts to hinder Alice's progress-more explicitly, her advancement towards maturity.

Lewis Carroll had been reported to be the image of an undiminished Victorian Clergyman, whom Virginia Woolf termed as a man who “had no life” [xvii] . He was the adult, stuck in a shy and prim shape of perpetual childhood. Carroll unwittingly depicted this image of his duality in the characters of the blue caterpillar and the grinning Cheshire Cat. The caterpillar who sits on the top of the mushroom is like everyone else (the animals per se) in Wonderland: it pretends to be harsh to a child like grownup adults, but deliberately fails to do so and it is revealed in their unwitting anxiety when counterpointed or questioned. He pretends to be like a stern school-master when he investigates Alice and tells her to repeat numerous poems but ultimately he has the infantile complex for sexuality, which Carroll expresses in an unwittingly phallic reference:

“Well, I should like to be a little larger, sir, if you wouldn't mind,” said Alice: “three inches is such a wretched height to be.”

“It is a very good height indeed!” said the Caterpillar angrily, rearing itself upright as it spoke (it was exactly three inches high)

The contrast between Alice's ‘penis-envy' and the Narrator's almost “neurotic” (a)sexuality [xviii] conveys Carroll's anxiety for the growth of little girls and eventually leaving their ‘pure' state. The caterpillar therefore is insufficient in this regard. The Cheshire cat, on the other hand, is the philosophical (logical or rational rather) self of the author, calm, detached and composed. He is the good object, the good penis, the ideal voice of the heights. He incarnates the disjunctions of the new position, being on top of everything in Wonderland, often unharmed or wounded, suggests the Narrator's unaffected self of worldly affliction. He appears and disappears, leaving only his smile or forms itself from the smile of the ‘good object' or as Delueze terms it, “the liberation of sexual drives.”

Contrasting with the artistic fascination of the pure ‘sexually uncorrupted' girl child, Carroll also depicts an almost sexual repulsion towards grown women. In the chapter 6 of the first book, ‘Pig and Pepper', Alice is stumbled upon a large, smoky kitchen and discovers an atmosphere permeated with pepper, a sneezing duchess and a howling and a sneezing baby, while later develops rather a ghastly parody to the Victorian motherhood:

“Speak roughly to your little boy,

And beat him when he sneezes;

He only does it to annoy,

Because he knows it teases.”

CHORUS (in which the cook and the baby joined) :- “Wow! wow! wow !”

While the Duchess sang the second verse of the song, she kept tossing the baby violently up and down, and the poor little thing howled so, that Alice could hardly hear the words :-

“ I speak severely to my boy,

I beat him when he sneezes ;

For he can thoroughly enjoy

The pepper when he pleases!”

CHORUS “Wow! wow! wow !”

Although it is the obvious parody of David Bates' poetry ‘Speak gently to the little child', but there are some concealed sinister intention behind it. The pepper is analogous to a sexual stimulant and Tenniel's clever illustration of the long phallic pepper container [xix] in the cook's hand makes the reference a little more than obvious. In the later chapter, ‘The Mock Turtle's Story' the rather queer behaviour of the Duchess “to rest her chin upon Alice's shoulder” and Alice's discomfort establishes the effect of the aphrodisiac pepper that, to the Duchess “that makes people hot-tempered”. The episodes with the Duchess can be viewed with the same angle with which the Pigeon had viewed Alice: Corruptive, decaying and harbinger of death.

Critic Carol Mavor's [xx] observation of Carroll preserving his little friends as everlasting and beautiful photographs has been reflected in the theme of the talking flowers in Through the Looking Glass. She had viewed Carroll's photographic plates as the everlasting flower-beds where little girls could be preserved before their eventual womanly bloom, before their unstoppable wilt. Part of the appeal of understanding little girls without sex plays a vital role in the avoidance of death, as little girls leave their childhood bed to their marriage bed and eventually their death bed. The world of Looking Glass unlike the Wonderland becomes a metaphor of death itself. The winter voyage to the Looking glass land, contrasting to the May voyage to Wonderland becomes a steady metaphor of death and the cryogenic preservation of youthfulness. There seems to be a connection in Dodgeson's mind between the death of childhood and the development of sex.

‘How is it you can all talk so nicely?'Alice said, hoping to get it into a better temper by a compliment. ‘I've been in many gardens before, but none of the flowers could talk.'

‘Put your hand down, and feel the ground,' said the Tiger-lily. ‘Then you'll know why.

Alice did so. ‘It's very hard,' she said, ‘but I don't see what that has to do with it.'

‘In most gardens,' the Tiger-lily said, ‘they make the beds too soft- so that the flowers are always asleep.'

The grounds stand for a frozen reality as well as deathbed when the flowers talk about why the mortal flowers are always quiet. The Red King's sleeping presence is felt soon enough, alluding to Carroll's tendency to fall asleep while telling the stories to the Liddell girls. Alice has already “begun to fade” as the talking flowers observe and she is going to die if the Red King wakes up.

“We all win”-do we? : Caucas[ians], Darwin and the theme of Hunger

The metaphor of the Caucus race in ‘Alice in Wonderland' has a double connotation in the context of the story. The word is a fragmented version of the term ‘Caucasians', that plays on (mainly) on the futility of White Man's Superiority in the Age of Darwin and the double standards of the prent Democrats. In this business of the ‘Caucases' as it is depicted in the Queen of Heart's Croquet ground, follow no specific grounded rules to play the games, they ‘improvise' as they go, like popular Democrats. One can start running whenever he liked and leave the same way. It was a ‘game' where everyone won, despite the impending Doom of the fear of Extinction presented in the character of the Dodo bird. Carroll, juxtaposing laughter with the grim themes of death, simply laughs at the fanatical Victorian rejection to Darwin, saying: “the insufficiency of ‘Natural Selection' alone to account for the universe, and its perfect compatibility with the creative and guiding power of God” (Lewis Carroll's Diaries, 1871-1874).

When Alice has her moment of isolation in the Subterranean Wonderland as she says “so very tired of being all alone here” [xxi] she voices out the very Victorian shock of Faith. She is alone in a world where she is considered as the ‘Other' in the emptiness of the Nature of Wonderland. The fault however lies in Life itself. Carroll's ‘Alice' stories live and breathe quite deeply in the thought of Darwinian Evolution process, given the fact that it was a raging topic of discourse during the 1860's, only five years before Carroll published his stories. In numerous expressions, especially the crocodile's ‘jaws' and ‘claws', William Empson has pointed out how high a proportion of the jokes, poems and parodies in the ‘Alice' books hinge upon death and eating. The secure domestic order of Alice's moral universe is exposed to reveal terror and appetite. ‘Wonderland' sounds Edenic, as do many of Dodgson's accounts of childhood, but the world of the stories are more akin to Tennyson's ‘Nature red in Tooth and Claw' than Wordsworth's ‘fair seed-bed'; it's overshadowed by fear and death and extinction. Readers of Alice in Wonderland are likely to notice that the animal characters do not behave or talk much like animals in traditional fairy tales or fables. Neither they are helpers nor monsters, nor do they teach lessons about kindness to animals. Instead they talk in chopping logic, competing Alice and each other, and often mentioning things “natural” to animals might be imagined to talk about: fear, death or being eaten. Denis Crutch is also roughly right when he points out that there is in Alice a hierarchy of animal equivalent to Victorian class system but also suggesting a competitive nature that

Fig 6: The Duchess, the Baby and the Cook by John Tenniel. (The Red Boxed area denotes the phallic shape and position of the container that contains aphrodisiac pepper.)

of the Darwinian model and therefore bringing up a new perspective of Herbert Spencer's ‘Social Darwinism'. The white rabbit, the caterpillar and the March Hare seemed to be gentlemen, frogs and Fish are footmen, Bill the lizard is bullied by everybody, hedgehog and flamingos are being ‘used of' and the dormouse and the guinea pigs are victimised by the larger humans: symbolising the Aristocrats, Middle class, Outcasts, Working Class and the Exploited.

If we go backwards in the story, and from there continuously advance, we can surely spot Alice's predatory tendencies and her denial of it. In fact she seems to be possessed by the ‘Cannibal' [xxii] demon that changes the hard working bee into a small hungry Crocodile and that rages in the pool eveoking to the fright of the little inhabitants, ghosts of devouring dogs and cats.

Alice had no very clear notion how long ago anything had happened.) So she began again: “Ou est ma chatte?” which was the first sentence in her French lesson-book. The Mouse gave a sudden leap out of the water, and seemed to quiver all over with fright. “Oh, I beg your pardon!” cried Alice hastily, afraid that she had hurt the poor animal's feelings. “I quite forgot you didn't like cats.”

“Not like cats!” cried the Mouse, in a shrill, passionate voice: “Would you like cats if you were me?”

“Well, perhaps not,” said Alice in a soothing tone: “don't be angry about it. And yet I wish I could show you our cat Dinah: I think you'd take a fancy to cats if you could only see her. She is such a dear quiet thing,” Alice went on, half to herself, as she swam lazily about in the pool, “ and she sits purring so nicely by the fire, licking her paws and washing her face-and she is such a nice soft thing to nurse-and she's such a capital one for catching mice--oh, I beg your pardon !” cried Alice again, for this time the Mouse was bristling all over, and she felt certain it must be really offended. “We won't talk about her any more if you'd rather not.”

In this process, she wants above all to stay in command of Wonderland, and reaches time and again for the devices which seems so natural when she learned them-the predatory hierarchy for instance. She tends to understand and value levels of being in terms of who eats what or whom. A grisly view of this ‘genteel disguise' is apparent in the child's musing: “do cat eat bats... do bat eat cats?” Alice can insert here any warm blooded noun related to her native Fauna: bat, rat, goat, slug, or Alice herself-as long as the key, ‘eat', reminded constant. She seems unable to avoid connecting the eaters with their dinners, chatting up mice and birds about cats and turning a delightful lobster quadrille into a feast, where the merry dancers are threatened by her own practices-“I've often seen them at dinn-.” The Mock-Turtle scene becomes significant in the context of both Darwinian-Victorian ambition of ascending the social hierarchy and the terms of hunger. Mock turtle is presented as both the symbol of object of appetite on the table and Alice's emancipation to grow up as an adult in her own world as Mock-turtle is the ingredient of a very grown-up, alcoholic, post dinner, veal soup. The theme of such exaggerating hunger in a little girl may arise from Carroll's own perception of the appetite of those little girls who had visited his Old and Bachelor days; critic Stuart Dodgson Collingwood even mentions that Carroll will go to such ends to comment on the little girls' eating habit with mild indignation and soft alarm: “she eats a great deal too much”.

The importance of the theme of predation, “the motif of eating and being eaten” is such that it has attracted a number of commentaries, especially in Margaret Boe Birns in “Solving the Mad Hatter's Riddle” and Nina Auerbach's in “Alice and Wonderland: A Curious Child”. Birns remarks “most creatures in Wonderland are relentless carnivores, and they eat creatures who save for some outer physical differences, are very like themselves, united, in fact, by a common ‘humanity'.” The critic even cites a crocodile-eating fish as a case of “cannabalism”. In this context we may recall Alice's statement in the First chapter of Through the Looking Glass: “Nurse! Do let's pretend that I'm a hungry hyaena and you're a bone” (line 8). The reference of the idea “eat or be eaten” becomes most poignant in the last scene when the Food of Queen Alice's dinner party “begins to eat the guests”, which has been granted by Auerbach as “most sinister and Darwinian aspects of nature.” Carroll however, like the Chesire Cat has the last grin, when we remember how he views the ‘Evil' in the Life in ‘The Lesson': “Why, it's LIVE backwards” (Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, 1893) [xxiii]

Queen Alice: Politics, Law and the Attaining Female Autonomy

‘Wonderland' and ‘Looking-Glass land' present itself in a very Kafka-like symbolism: Wonderland is a dream and Looking-glass land is self-consciousness. This is especially prent if we are to understand how Alice's imagination and thoughts of innocent daydreams were influenced by the contemporary socio-political crises surrounding her. The Looking-glass land, as we will see is far too similar to England: it's bleak, it's cold and it's filled with political tensions.

By the time Alice comes an end to the adventure of Wonderland, she is no more the ‘Sweet summer child' of May-time voyage, she is a grown up, and knows when to voice herself. The alarming rate of Alice's growth in the courtroom symbolises her as the ‘New Woman' of Victorian era, often regarded as a woman out of place and time: formidable and autonomous, the subject of patriarchal anxiety. Alice's growth in the courtroom is the graduation of her as the supine, problematic body in the first few chapter of the ‘Alice in Wonderland': she is now the master of her will and she is no more the object, like white rabbit's hand-maid. Alice becomes symbolic of She-who-must-be-obeyed, the female supreme defined in H. Rider Haggard's She.

“I can't help it,” said Alice very meekly: “I'm growing.”

“You've no right to grow here,” said the Dormouse.

“Don't talk nonsense,” said Alice more boldly: “you know you're growing too.”

“Yes, but I grow at a reasonable pace,” said the Dormouse: “not in that ridiculous fashion.”

Flustered by the threateningly large presence of Alice in his courtroom, the King (who sits as judge in this proceeding) tries his best to make her leave. From his position of authority, he declares the law, which, it appears, he just made up. When Alice gets nowhere disputing the facts (she is not a mile high), she questions the law itself. At this point, the King confidently invokes precedent ("It's the oldest rule in the book"), but it is not at all lost on Alice that this argument makes no sense. When women started to claim their right to be in the world of law, to make and interpret law in both legislatures and courtrooms, judges found they stumbling, like the King, for applicable rules to keep them out. [xxiv]

At this moment the King, who had been for some time busily writing in his note-book, called out "Silence!" and read out from his book

"Rule Forty-two. All persons more than a mile high to leave the court."

Everybody looked at Alice.

"I'm not a mile high," said Alice.

"You are," said the King.

"Nearly two miles high," added the Queen.

"Well, I sha'n't [sic] go, at any rate," said Alice: "besides, that's not a regular rule: you invented it just now."

"It's the oldest rule in the book," said the King.

"Then it ought to be Number One," said Alice.

The King turned pale, and shut his note-book hastily.

Children like to think that being small they can hide from the grownups, and if they get big enough they can certainly control the grownups. This simple binary of growth and shrinking adds a greater significance in the world of wonderland. By her autonomous choice of growing and shrinking at will, In the utopian dreamland, Alice the ‘New-woman' like Sue Bridehead of Hardy, or Eliza Doolittle of Shaw, can dream of emancipation to stand against the ‘grown-ups' or more explicitly, the Men.

Scattered and anachronic historic elements make themselves heard as Alice's protest as a child in the Political Adult World. If we are to juxtapose Alice's last incident, and the moment before she enters the Looking-Glass land, obliterating the months in between, we can anticipate what waits in the Looking Glass Land. The final effect she has on the Queen of Heart's court by saying “you're nothing but a pack of cards” is similar to the explosion intended for Jacobean Parliament at November 5th , 1605, commonly known as the Gunpowder Plot; the association becomes even more poignant when we see Alice in the first chapter of the ‘ Through the Looking Glass ' pondering over those matter in a rather chilly day of November the 4th . The anachronic juxtaposition and wishful fulfilment of the explosion of ‘Guy Fawkes Day' at the end of the first book is symbolic of Alice's emancipation to experience the adult's power.

To Alice's defence, Carroll depicts several failures of Adults who attempt to control the children and the political situation of their country. The elements of Looking-Glass land are very colour specific and warlike, and in the War Theme there, is a stark and Nostalgic Contrast of England in the Past and England Now. In the Mirror image of the ‘Brillig' poem, ‘Jabberwocky', there is a romanticising element for war, which linguistically and ideologically mimics the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf, especially the last episode of Beowulf against the Mighty Dragon. ‘Humpty Dumpty' too, represents a strong symbol related to war. Carroll derives the egg-like characters from James William Elliot's nursery rhyme with the same title, which has been debated by critics to have been inspired from an historical incident. The name ‘Humpty-Dumpty' was given to King Charles I's cannon which were fired during the 1646 civil war against the parliamentarians. The assault was futile, as ‘Humpty' toppled and could not be erected again, which results the abdication of Charles I. The employment of Humpty-Dumpty may be seen as an ominous symbol for two reasons: the prent democratic tension within the English parliament and the colonial uproar overseas, threatening the Victorian Empire.

As much as there is nostalgia in the Looking Glass Land, there are also some prophetic symbols that emerge every now and then. The land spread out on an infinite chessboard of red-and-white colour, which serves to identify two symbols: in one hand it is the central colour of England's St. George's Cross, while in the other it anticipates condition of England as wrapped in Blood and Bandage, war-torn and war-fatigued, fifty years from the time the story was written. Alice goes quickly through the first square by railway, in a carriage full in animals in a state of excitement about the progress of business and machinery, the only man Disraeli, dressed in newspaper-the new man who gets on by self-advertisement, the man who believes in progress, possibly even the rational dress of the future.

“...to her great surprise, they all thought in chorus (I hope you understand what thinking in chorus means- for I must confess that I don't), ‘Better say nothing at all. Language is worth a thousand pounds a word!'

‘I shall dream about a thousand pounds tonight, I know I shall!' thought Alice.

All this time the Guard was looking at her, first through a telescope, then through a microscope, and then through an opera- glass. At last he said, ‘You're travelling the wrong way,' and shut up the window and went away.”

[xxv] This seems to be a prophecy; Huxley in the Romanes lecture in 1893, and less clearly beforehand, said that the human sense of right must judge and often be opposed to the progress imposed by nature, but at this time he was still looking through the glasses. In 1861 “many Tory members considered that prime minister was a better representative of conservative opinion that the leader of the opposition”. If we are look at chapter 7 of Through the Looking Glass, we can see the Lion and the Unicorn are fighting for the crown. Obviously enough, the Lion represents the current representative of the British Parliament and the Unicorn, as a mythical creature; represent the aspiring rival party, waiting to supplant the Lion. The Red King, symbolically the Monarch of England, to whom the crown actually belongs, stands entirely plebeian and dormant.

In the cold and decaying political atmosphere of the Looking Glass land, Alice is compelled to abandon her ambition to be a grown-up throughout the narrative. From the embryonic character of the Humpty-Dumpty to the “great school boys” Tweedledum and Tweedledee, even the passengers in the train have evoked a sort of repulsion for eternal childhood in her. When Humpty-Dumpty says “if you'd ask my advice... I'd have said ‘Leave off at seven'” Alice promptly answers “I never ask anything about growing” [xxvi] . The discrepancy between appearance and reality, as exemplified in the Tweedles' appearance: they are clearly ‘men' but they look like “a couple of great school boys.” After attaining her autonomy in the Queen of Heart's court, she no longer wishes to be confined in her childlike state, and there is only thing that can free her, the political power and in her steadfast ambitious Alice declares “I want to be the queen.” She rejects the White Knight´s claim on her, pointing out that she will not let anybody to take her freedom from her. Alice clarifies to him that she wants to be a Queen, which indicates that she will be above him in the social hierarchy. Again, Alice consciously diminished the White Knight´s significance, because he is a male figure who attempts to reduce her being into a mere object of both his personal ambition and his masculine authority.

Her unceasing energy to aspire towards the Queen´s position is seen as she moves through the chess board, contemplating the best and the quickest way to get to her desired aim, reflecting that, “I think I´ll go down the other way,” she said after a pause; “and perhaps I may visit the elephants later on. Besides, Ido so want to get into the Third Square‟”! Considering the fact that Alice takes part in a serious play, she is at this moment calculating and considering her ensuing steps which would secure her leading position on the chess board. Hence, applying this onto the social scale, her victory would also exemplify her successful potential which solidifies her status as a grown woman. Alice rejoices over the idea that she is almost at the end of her long adventures, exclaiming that, “„and now for the last brook, and to be a Queen! How grand it sounds‟” the brook, again like the pool of tears is immensely significant: it is the waters of Lethe that will help her to leave her childhood behind and make her the ‘Queen', the adult woman. Alice´s euphoria marks her realization of the exploration of her female condition and personal attainment which are the direct outcome of her ability to form her own female character, reaching out across social barriers of her time.

Conclusion

Wonderland is not Barrie's Neverland where children retain their youth for eternity. Carroll's world is as imaginative, idyllic and innocent as it is harsh and real. Alice as a child has fulfilled her fantasies of being a ‘grown-up', and as a ‘grown-up' she had seen the harshness, the competitive nature of real life-and in her simulation of an adult she crosses the faint line between childhood and adulthood, with anxiety, identity crises, loneliness and challenges of her world. In response to Alice´s narrative, the author gives us the picture of her sister´s train of thoughts by remarking that, “Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman...and how she would gather about her other little children, and make their eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago”. In this passage it is apparent that the narrator naturally connects Alice to the Victorian society by basically summing up what awaits her in the foreseeable future since her sexual category biologically predetermines that for her. The bleakest part of growing up is: “It's no use going back yesterday” to the “different person” called the ‘child'. When the adult cannot slow down the growth of the child, all he can do is to bid the saddest farewell like the dying old wasp: “good-bye and thank-ye” [xxvii]

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Smt Gargi Gangopadhyay my term paper supervisor, Smt Indrani Choudhury Dutt, the Academic Co-ordinator of Lady Brabourne College, Department of English (Post Graduate), Smt Sudeshna Das, Head of English Department, for their diligent guidance and impartial support. Without their help this paper would not have been conceived.

Bibliography

Ariès, Philippe. Centuries of Childhood. Translated by Robert Baldick, Vintage Giant, Paris, 1960, Print.

Becker Lennon, Florence “Escape into the garden” Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Harold Bloom. 1st Indian edition. Viva Modern Critical Interpretations. New Delhi, 2007.

Bivona, Daniel. “Alice the Child-Imperialist and the Games of Wonderland” Nineteenth-Century Literature . Vol. 41, No. 2 (Sep., 1986), pp. 143-171, University of California Press. JSTOR. Web. 17 May 2012. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/3045136 >

Bloom, Harold. Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. 1st Indian edition. Viva Modern Critical Interpretations. New Delhi, 2007.

Carroll, Lewis. Alice in Wonderland. 2nd Ed. Donald J Gray, New York, Norton, 1992. Print.

Sylvie and Bruno Concluded. Harry Furniss, United Kingdom, Macmillan publishers, 1989. Print.

‘The Wasp in a Wig', Alice in Wonderland. 2nd Ed. Donald J Gray, New York, Norton, 1992. Print.

Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson. “The Old Bachelor”. Alice in Wonderland. 2nd Ed. Donald J Gray, New York, Norton, 1992. Print.

Del Nino, Maurizio. “Naked Raw Alice.” Semiotics and linguistics in Alice's world. Walter De Gruyter, New York, 1994. Print

Deleuze, Gillies. “Thirty Third Series of Alice's Adventures”. Alice in Wonderland. 2nd Ed. Donald J Gray, New York, Norton, 1992. Print.

Empson, William. “ Alice in Wonderland: The Child as Swain”. Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. 1st Indian edition. Harold Bloom. Viva Modern Critical Interpretations. New Delhi, 2007.

Fordyce, Rachael, Carla Marello. Semiotics and linguistics in Alice's world. Walter De Gruyter, New York, 1994. Print.

Freud Sigmond, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, Translated by A. A. Brill, Arcadia eBook, 2015, Web.

Greenacre, Phyllis. “The Character Of Dodgson As Revealed In The Writings Of Carroll” Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Harold Bloom. 1st Indian edition. Viva Modern Critical Interpretations. New Delhi, 2007.

Gubar, Marah. “Reciprocal Agression”. Alice in Wonderland. 2nd Ed. Donald J Gray, York, Norton, 1992. Print

Haughton, Hugh “Introduction” to Alice's Adventure in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Lewis Carroll, United Kingdom, Macmillan Publishers, 2007, Print.

Jung, Carl Gustuv, Aspects of the Feminine, Translated by: R.F.C. Hull. Routlage, London, 1982. Print.

Kalsem, Kristin (Brandser), “Alice in Legal Wonderland: A Cross-Examination of Gender, Race and Empire in Victorian Law and Literature”, University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications, Vol 1 Paper 14, (Jan, 2001), pp 1-35, University of Cincinnati Press, Web, < http://scholarship.law.uc.edu/fac_pubs/14>

Kincaid, James R. “Alice's Invasion of Wonderland”. PMLA. Vol. 88, No. 1 (Jan., 1973), pp. 92-99. Modern Language Association . JSTOR. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/461329>

Leach, Caroline, “Dodgeson's friendship with Women”. Alice in Wonderland. 2nd Ed. Donald J Gray, York, Norton, 1992. Print

MacDonald, Alex. “Utopia Through the Looking Glass: Lewis Carroll as Crypto Utopian”. Utopian Studies. No. 2 (1989), pp. 125-135. Penn State University Press. JSTOR, Web, 2nd May, 2017. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/20718914 >

Mavor, Carol. “Utopographs or The Myth Of Everlasting Flowers” Alice in Wonderland. 2nd Ed. Donald J Gray, York, Norton, 1992. Print.

Petersen, Calvin R. “Time and Stress: Alice in Wonderland”. Journal of the History of Ideas. Vol. 46, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1985), pp. 427-433. University of Pennsylvania Press. JSTOR, Web, 1st May, 2017. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2709477>

Rackin, Donald. “Love and Death in Carroll's Alices. ” Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Harold Bloom. 1st Indian edition. Viva Modern Critical Interpretations. New Delhi, 2007.

Rackin, Donald. “The Alices and Modern Quest For Order” Alice in Wonderland. 2nd Ed. Donald J Gray, York, Norton, 1992. Print.

Raszková, Jana, “Challenging Victorian Girlhood in Alice´s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-glass” , Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies: Bachelor's Diploma Thesis, pp 1-44, University of Masaryk Press, 2011 , Print.

Smith, Rose Lovell. “The Animals of Wonderland: Tenniel as Carroll's Reader”. Criticism. Vol. 45, No. 4 (Fall 2003), pp. 383-415. Wayne State University Press. JSTOR. Web, 1st May, 2017. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/23126396>

[i] From Stuart Dodgson Collingwood's “The Old Bachelor”

[ii] From ‘Thirty Third Series of Alice's Adventures' by Gillies Deleuze

[iii] From Florence Becker Lennon's ‘Escape into the Garden'

[iv] See fig 1, Illustration of Alice in wonderland by John Tenniel.

[v] See fig 2, Illustration of Alice in wonderland by John Tenniel

[vi] From, Carl Gustav Jung's ‘Aspects of the Feminine'

[vii] From ‘Thirty Third Series of Alice's Adventures' by Gillies Deleuze

[viii] From Alice in Wonderland (Norton Critical Edition): edited by Donald J Gray, pg 13, lines 1-5

[ix] See fig 3, Illustration of Alice in Wonderland By John Tenniel

[x] See fig 4

[xi] See fig 5 illustration

[xii] From Through the Looking Glass, ed. By Donald J Gray, Norton Edition, 2013, Pg 120, Line 13-21

[xiii] From ‘Time and Stress: Alice in Wonderland' by Calvin R Peterson

[xiv] From Phyllis Greenacre, “The Character Of Dodgson As Revealed In The Writings Of Carroll”

[xv] From the prologue of Alice's Adventures in the Wonderland, ‘Golden Afternoon' by Lewis Carroll

[xvi] From Stuart Dodgson Collingwood's “The Old Bachelor”

[xvii] From Caroline Leach, ‘Dodgeson's friendship with Women'

[xviii] From Sigmund Freud, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex.

[xix] See fig 6 illustration of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by John Tenniel

[xx] From Carol Mavor's ‘Utopographs or The Myth Of Everlasting Flowers'

[xxi] From ‘The Alices and Modern Quest For Order' by Donald Rackin

[xxii] From Maurizio Del Nino's ‘Naked Raw Alice'

[xxiii] From Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, By Lewis Carroll,

[xxiv] From ‘Alice in Legal Wonderland: A Cross-Examination of Gender, Race and Empire in Victorian Law and Literature' by Kristin (Brandser) Kalsem (Harvard Women's Law Journal)

[xxv] From William Empson's ‘ Alice in Wonderland: The Child as Swain'

[xxvi] From Marah Gubar's ‘Reciprocal Agression'

[xxvii] From the unpublished chapter of Through the Looking Glass ‘The Wasp in a Wig'