World Literature

Luis Cernuda

BORN: 1902, Seville, Spain

DIED: 1963, Mexico City, Mexico

NATIONALITY: Spanish

GENRE: Poetry, criticism

MAJOR WORKS:

Reality and Desire (1936)

The Clouds (1940)

Desolation of the Chimera (1962)

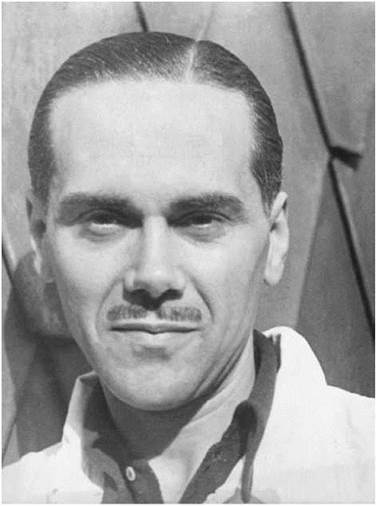

Luis Cernuda. Archivo de la Residencia de Estudiantes, Madrid

Overview

A member of the “Generation of 1927’’ of Spanish modernist poets, Luis Cernuda wrote frank verses of both homosexual love and deep pessimism. His poetry is distinguished by its starkly solitary and individualistic spirit, its sharp social criticism, and its unrelenting self-examination in both spare and colloquial language. Famed Mexican poet Octavio Paz observed in a critical essay titled On Poets and Others that Cernuda’s work, ‘‘is one of the most impressive personal testimonies to this truly unique situation of modern man: we are condemned to a promiscuous solitude and our prison is as large as the planet itself.''

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Desire, Love, and Alienation. While Cernuda’s pessimistic worldview has often been attributed to an introverted and sensitive character, critics also speculate that his melancholic, defiant poetic voice resulted from a painful sense of isolation brought about by his open homosexuality and years spent in exile abroad. Cernuda began writing poetry while still a law student at the University of Madrid. He became a protege of the poet Pedro Salinas, who helped him publish his first verse collection, Perfil del aire (Profile of the Air) in 1927. The poet's highly refined lyric verses showed the influence of Salinas and his contemporary, Jorge Guillen, among others, and received only a lukewarm reception. Cernuda began finding his own voice in two collections of surrealist-influenced poetry, Un rio, un amor (A River, a Love, 1929) and Losplaceresprohibidos (The Forbidden Pleasures, 1931). In these books, the poet experimented with incongruous word juxtapositions and spontaneous derivations from chance stimuli to express his sexual and metaphysical turmoil.

These verses also introduce a number of recurrent themes in Cernuda's work: desire and its relationship to love and reality; the hopeless search for wholeness and a yearning for oblivion; a deep hostility to the city and its imprisoning social conformity; and a keen appreciation of the transcendent mystery of nature. Also present in the poetry is the poet's negotiation of his experiences of homosexual love, in defiance of his time and culture. ‘‘For Cernuda, love is a break with the social order and a joining with the natural world. He exalted as man’s supreme experience the experience of love’’ wrote Octavio Paz. In still-Catholic Spain of the early twentieth century, this exaltation of homosexual love as a joining with the natural world—while hardly without important poetic predecessors (for example, Walt Whitman)—met with much resistance.

Cernuda published two additional important, surrealist-influenced collections in the mid-1930s, Donde habite el olvido (Where Forgetfulness Dwells) and Invocaciones (Invocations), before issuing the first edition of his definitive work, La realidad y el deseo (Reality and Desire), in 1936. A collection of new and previously published verse, this book was revised and expanded in subsequent editions to include most of Cernuda’s poetry. Critics have pointed out that La realidad y el deseo can be read as the poet’s emotional and spiritual autobiography. The book also chronicles Cernuda’s stylistic development over the years.

War and the Pain of Exile. A predominant theme in La realidad y el deseo is exile—both the spiritual exile Cernuda felt in Spanish society and the physical exile he experienced after the Spanish Civil War. The poet denounces such hallowed Spanish institutions as the patriarchal family and the Catholic Church, and decries the backwardness, intolerance, and violence he finds in his homeland. Yet in many poems from the subsequent collections Las nubes (The Clouds) and Como quien espera el alba (As One Awaiting Dawn), Cernuda also reveals a deep, nostalgic longing for the Andalusian gardens and sea of his childhood. Along with many of his contemporaries in literature and the arts, Cernuda left Spain shortly before the Republican defeat of 1939—the triumph of General Franco’s dictatorship—and spent the remainder of his life in exile in Europe, the United States, and Mexico.

Las nubes (1940), Cernuda’s first volume published abroad chronicles his concerns for Spain and the alienation he felt as a result of his separation from it. During his years as an expatriate, Cernuda was greatly influenced by the meditative poetry of Robert Browning and T. S. Eliot. In the collections Como quien espera el alba (1947), Vivir sin estar viviendo (To Live without Being Alive, 1949), and Con las horas contadas (With the Hours Counting Down, 1956), he increasingly shifted his ongoing search for self-knowledge through alternative voices and colloquial speech free of more flowery rhetoric. Cernuda’s final collection, Desolacion de la quimera (Desolation of the Chimera, 1962), reflects his growing preoccupation with death in its summary of his lifelong search for self-affirmation. Critics observe that in these poems the perfect state of desire pursued in earlier collections loses its significance, while the quest itself becomes the primary motivation for Cernuda. Derek Harris has asserted: ‘‘The resolution with which he pursued his self-analysis, is, in the last resort, more important than his success or failure to find his ideal of harmony between reality and desire... . The clash between reality and desire in Cernuda’s own life was the stimulus that led him to seek to come to an understanding of himself through his poetry, and by doing this, so to create himself in his poetry.’’

In addition to his verse, which appears in English translation in The Poetry of Luis Cernuda (1971) and Selected Poems of Luis Cernuda (1977), Cernuda published several highly regarded critical texts on modern Spanish poetry, including Estudios sobre poesia espanola contemporanea (Studies on Contemporary Spanish Poetry, 1957) and Poesia y literatura (Poetry and Literature, 1960).

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Cernuda's famous contemporaries include:

William Carlos Williams (1883-1963): One of the most celebrated U.S. poets of all time, Williams was associated with both modernism and imagism and was also a practicing physician for many years.

Salvador Dali (1904-1989): The quintessential surrealist painter, Dali was born in Spain, but was fond of highlighting his Arab descent, tracing his lineage to the Moors who occupied southern Spain for close to eight hundred years.

Fulgencio Batista (1901-1973): Military dictator of Cuba until his 1958 ousting by Fidel Castro's guerrilla movement; his downfall signaled the success of the Cuban Revolution.

James Joyce (1882-1941): One of the most highly regarded literary figures of the twentieth century, this Irishman is best known for his short stories and novels. These include Dubliners (1914), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), Ulysses (1922), and Finnegans Wake (1939).

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986): Borges's novels are beloved around the world, and he is considered by many to be the preeminent Argentine writer and thinker of the twentieth century.

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969): Eisenhower was the thirty-fourth president of the United States, from 1953 to 1961; prior to his presidency, he commanded the Allied forces in their defeat of the Axis powers in Europe during World War II.

Works in Literary Context

The Generation of 1927. Cernuda was a controversial member of the Generation of 1927, a group of important writers who revolutionized Spanish poetry by introducing innovative approaches and modern techniques to what had

become a staid poetic tradition. Described as solipsistic in its incessant self-examination and universal in its moralistic vision, Cernuda’s poetry promotes sexual desire, creative expression, and the recognition of natural beauty as the means of transcending mundane existence. In 1964, Octavio Paz asserted: ‘‘If it were possible to define in a phrase the place Cernuda occupies in modern Spanish-language poetry, I would say he is the poet who speaks not for all, but for each one of us who make up the all. And he wounds us in the core of that part of each of us ‘which is not called glory, fortune, or ambition’ but the truth of ourselves.’’

The poems in Cernuda’s first two collections, Perfil del aire (1927) and Egloga, elegia, oda (Eclogue, Elegy, Ode, 1928), reflect his early interest in both Symbolism and classicism. While initially dismissed as facile, these works have been reassessed as impressive evocations of ambivalent adolescent emotions. After Cernuda became aware of his homosexuality during the late 1920s, he began to express through surrealist verse the turmoil that he was experiencing. In many of the poems contained in Un rio, un amor (1929), Los placeres prohibidos (1931), and Donde habite el olvido (1934), Cernuda utilizes free association of images and events to express particular emotions and to voice his reaction to society’s hostility toward his erotic desires. Stephen J. Summerhill commented: “Surrealism ‘humanized’ [Cernuda’s] poetry in the sense that it encouraged him to speak his deepest passions for the first time; and it gave him an artistic form with which to control these feelings, which were always on the verge of being inexpressible.’’

A Return to the Real, and Beyond Influenced by early nineteenth-century German lyric poet Friedrich Holderlin, Cernuda abandoned surrealism in Invocaciones (1934) in order to present his increasing personal alienation as a metaphor for the modern human condition. Cernuda’s wider scope is further elaborated in La realidad y el deseo (1936), which critics term his ‘‘spiritual autobiography.’’ Consisting of previously published and unpublished collections, this volume was revised on three occasions and ultimately encompassed nearly all of Cernuda’s poetic work. As reflected in the title, which translates as ‘‘Reality and Desire,’’ these poems reflect Cernuda’s attempt to transcend reality and to achieve self-affirmation through understanding and fulfilling personal desires. Philip Silver commented: ‘‘As Cernuda employs it, deseo is eros, a ‘desirous longing for.’ It is the product of the radical solitude, the gesture of seeking to bridge the gulf between the poet and ‘otherness,’ for to desire is, in Cernuda’s vocabulary, to long to be one with, and to be, the object of that desire.’’ In Cernuda’s poetry, sexual love ultimately gives way to poetic expression and nature as vehicles for eternal transcendence.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

The experience of exile—so central to Cernuda's life and poetry—has been characterized by some as the quintessential experience of modernity. Between two world wars, famines, and environmental catastrophes of unprecedented magnitude, and work-related, semi-forced migration at levels never before seen, the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have produced more experiences of—and more ways of experiencing—exile than any other period in human history. Here are a few other works by writers trying to come to terms with the experience of exile:

Doctor Faustus (1947), a novel by Thomas Mann. Nobel Prize winner Mann wrote this book in the United States, after fleeing both Nazi Germany and Switzerland during World War II. This novel is a fictional return to the Germany Mann left, and an attempt to come to terms with the society that had forced him out.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962), a novel by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Drawn from the author's experiences in internal exile within the Soviet Union, this novel traces the steps of a prisoner in one of Joseph Stalin's forced-labor camps and focuses on the human response to a reduction to bare survival.

The Stone Face (1964), a novel by William Gardner Smith. The Stone Face is the story of an African American man who has fled the oppressive racism of the United States, only to find that what had seemed a safe haven in France is predicated on his complicity in French racism against Algerians. Though an exile in France, Smith's protagonist realizes that solidarity with the oppressed is the only viable option, even when that threatens his own status.

Works in Critical Context

Luis Cernuda’s relationship with the reading public was uneasy from the outset of his poetic career. Although some reviews of his first book were encouraging, even enthusiastic, most were decidedly negative. Cernuda’s reaction was bitter, though understandable in light of his total commitment to his craft—a craft that involved deep challenges to some of Spain’s most cherished and intolerant institutions. Such an early and unflinching commitment also explains what was at times described as his fragile temperament and his unusual sensitivity to criticism. On the other hand, Cernuda was not only a most gifted poet but also a very acute reader of poetry— that of others as well as his own—and perceptive enough to realize that his continued experiments in poetic innovation would eventually earn him the attention of critics.

Residing in His Myth. Jose Angel Valente places Cernuda at the forefront of the Generation of 1927, noting that ‘‘two poets, the two greatest of their generation, already reside in their myth: Lorca and Cernuda.’’ This is not an isolated judgment. The important journal La cana gris dedicated a 1962 issue to Cernuda, in which key critics were unstinting in their praise. Jacob Munoz, editor of the issue, remarks on Cernuda’s decisive impact on younger generations of poets; Juan Gil-Albert affirms that Cernuda ‘‘has become fully what he already was incipiently for many: the greatest Spanish poet of his time’’; and Francisco Brines recalls his discovery of Cernuda’s Como quien espera el alba (Like Someone Waiting for the Dawn, 1947), which he read ‘‘slowly and amazed.’’ More recently, in considering the poem ‘‘Otras ruinas’’ (‘‘Other Ruins’’), literary critic Cecilia Enjuto-Rancel has noted that Cer- nuda ‘‘eschews the romantic vision of ruins, where the external landscape is a melancholic reflection of the speaker’s internal conflicts, his ruined self. By contrast, these poems historicize the process of destruction, which is often caused by war and progress, not time and nature.’’

Desolation of the Chimera. In Luis Cernuda: A Study of the Poetry (1973), Derek Harris describes Desolacion de la quimera as ‘‘an attempt to summarize the lessons [Cernuda] has learnt from the long investigation of himself. This final collection of poems is his own conclusion to his life, produced under the shadow of a presentiment that he was soon to die, a presentiment that turns this book into a poetic last will and testament designed to leave behind him an accurate self-portrait and a duly notarized statement of his account with life.’’ Besides the occasional pieces and personal reminiscences, the principal topics dealt with in the collection are still love, Spain, and exile, as well as a series of poems on artists and on aesthetic experience. Love and art had been the central facts of Cernuda’s existence. It was of fundamental importance at this late stage of his life for him to reassert them as the sufficient, powerful justifications of his being.

Responses to Literature

1. It is often mentioned as a mark in a poet’s favor that his or her poems are universal. But much of what poets write about—such as Cernuda’s experience of being homosexual in early twentieth-century Spain— is deeply personal. What do you make of Octavio Paz’s assertion that Cernuda ‘‘is the poet who speaks not for all, but for each one of us who make up the all’’? Is this different from writing ‘‘universal’’ poems? If so, how? If not, why not?.

2. Research the significance of Spanish settings and history for Cernuda’s poetry. Why do you think Cernuda was so drawn to the traditions of a culture from which he felt deeply alienated? Support your thesis with detailed analyses of two to five poems.

3. Consider Desolation of the Chimera as a capstone to Cernuda’s career. Does this seem like an intentionally ‘‘final’’ book? Why or why not?

4. Read the poem ‘‘Otras ruinas’’ alongside two other modern poems about cities (by poets other than Cernuda—perhaps Octavio Paz or Charles Baudelaire). Compare and contrast ‘‘Otras ruinas’’ with the other two poems you have chosen, considering the poets’ differing attitudes toward time, the city, and modernity.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Barnette, Douglas. El exilio en la poesia de Luis Cernuda. Ferrol, Spain: Sociedad de Cultura Valle-Inclan, 1984.

Coleman, Alexander. Other Voices: A Study of the Late Poetry of Luis Cernuda. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

Harris, Derek. Luis Cernuda: A Study of the Poetry. Melton, England: Tamesis, 1973.

Hughes, Brian. Luis Cernuda and the Modern English Poets: A Study of the Influence of Browning, Yeats, and Eliot on His Poetry. Alicante, Spain: Universidad de Alicante, 1988.

Jiminez-Fajardo, Salvador, ed. The Word and the Mirror: Critical Essays on the Poetry of Luis Cernuda. Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1989.

Paz, Octavio. On Poets and Others. Trans. Michael Schmidt. New York: Seaver, 1986.

Quirarte, Vicente. La poetica del hombre dividido en la obra de Luis Cernuda. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, 1985.

Silver, Philip. “Et in Arcadia Ego’’: A Study of the Poetry of Luis Cernuda. Melton, England: Tamesis, 1965.

Periodicals

Brown, Ashley. ‘‘Cabral de Melo Neto’s English Poets.’’ World Literature Today 65 (Winter 1991): 62-64.

Enjuto-Rancel, Cecilia. ‘‘Broken Presents: The Modern City in Ruins in Baudelaire, Cernuda, and Paz.’’ Comparative Literature 59, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 140-57.