World Literature

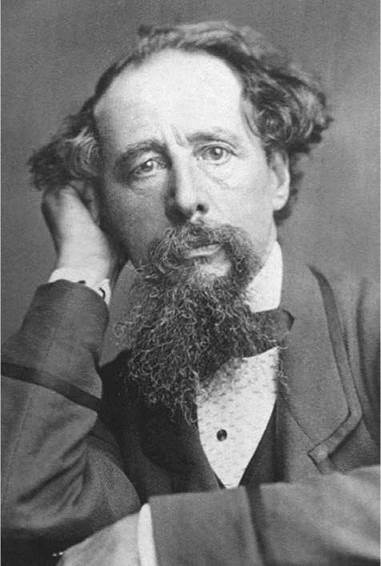

Charles Dickens

BORN: 1812, Portsmouth, England

DIED: 1870, Kent, England

NATIONALITY: English

GENRE: Fiction

MAJOR WORKS:

Oliver Twist (1837-1839)

A Christmas Carol (1843)

Bleak House (1852-1853)

A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

Great Expectations (1860-1861)

Charles Dickens. General Photographic Agency / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Overview

Charles Dickens wrote fourteen full novels as well as sketches, travel, and Christmas books, and was at work on his fifteenth novel when he died. He took chances, dealt with social issues, and did not shy away from big ideas. Almost all of Dickens’s novels display his comic gift, his deep social concerns, and his talent for creating vivid characters. Many of his creations, most notably Ebenezer Scrooge, have become familiar English literary stereotypes, and today many of his novels are considered classics.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Poverty and the Birth of Boz. Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812, at Port-sea (later part of Portsmouth) on the southern coast of England. He was the son of a lower-middle-class father whose lack of financial foresight Dickens would later satirize in David Copperfield. Dickens’s father constantly lived beyond his means and was eventually sent to debtor’s prison, a jail specially reserved for people who could not pay back their debts. This deeply humiliated young Dickens, and even as an adult he was rarely able to speak of it. At the age of twelve he was forced to work in a factory for meager wages. Although the experience lasted only a few months, it left a permanent impression on Dickens.

Dickens returned to school after an inheritance relieved his father from debt, but he became an office boy at the age of fifteen. He learned shorthand and became a court reporter, which introduced him to journalism and aroused his contempt for politics. By 1832 he had become a reporter for two London newspapers and, in the following year, began to contribute a series of impressions and sketches to other newspapers and magazines, signing some of them ‘‘Boz.’’ These scenes of London life helped establish Dickens’s reputation and were published in 1836 as Sketches by Boz, his first book. On the strength of this success he married Catherine Hogarth. She eventually bore him ten children.

Early Works

In 1836 Dickens began to publish The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club in monthly installments. Pickwick became one of the most popular works of the time. The comic heroes of the novel, the antiquarian members of the Pickwick Club, scour the English countryside for local points of interest and become involved in a variety of humorous adventures that reveal the characteristics of English social life. Later, however, the chairman of the club is involved in a lawsuit that lands him in debtors’ prison. The lighthearted atmosphere of the novel changes, and the reader is given hints of the gloom and sympathy with which Dickens was to imbue his later works.

During the years of Pickwick’s serialization, Dickens became editor of a new monthly, Bentley’s Miscellany. When Pickwick was completed, he began publishing his new novel, Oliver Twist (1837-1839), in its pages—a practice he later continued. Oliver Twist traces the fortunes of an innocent orphan through the streets of London. It seems remarkable today that this novel’s fairly frank treatment of criminals, prostitutes, and ‘‘fences'' (receivers of stolen goods) could have been acceptable to the Victorian reading public. But so powerful was Dickens’s portrayal of the ‘‘little boy lost’’ amid the lowlife of the East End that the limits of his audience's tolerance were stretched.

Dickens was now firmly established in the most consistently successful career of any nineteenth-century author after the Scottish novelist and poet Sir Walter Scott. He could do no wrong as far as his readership was concerned, yet for the next decade his books would not achieve the standard of his early triumphs. These works include Nicholas Nickleby (1838-1839), still cited for its expose of brutality at an English boys’ school; The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-1841), remembered for hitting a high (or low) point of sentimentality in its portrayal of the sufferings of Little Nell; and Barnaby Rudge (1841), still read as a historical novel, set as it is amid the anti-Catholic riots of 1780. Dickens wrote all these novels before he turned thirty, often working on two or three at a time.

In 1842 Dickens, who was as popular in America as he was in England, went on a five-month lecture tour of the United States, speaking out strongly for the abolition of slavery and other reforms. He returned to England deeply disappointed, dismayed by America’s lack of support for an international copyright law, its acceptance of slavery, and what he saw as the general vulgarity of American people. On his return he wrote American Notes, which sharply criticized the cultural backwardness and aggressive materialism of American life. In his next novel, Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-1844), the hero retreats from the difficulties of making his way in England, only to find that survival is even harder on the American frontier. During the years in which Chuzzlewit appeared, Dickens also published two Christmas stories, A Christmas Carol (1843) and The Chimes (1844), which became as much a part of the Christmas season as the traditional English plum pudding.

First Major Novels

After a year in Italy, Dickens wrote Pictures from Italy (1846). After its publication, he began writing his next novel, Dombey and Son, which continued until 1848. This novel established a new standard in the Dickensian tradition and may be said to mark the turning point in his career. As its full title indicates, Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son, the novel is a study of the influence of the values of a business society on the personal fortunes of the members of the Dombey family and those with whom they come in contact. It takes a somber view of England at midcentury, and its mournful tone becomes characteristic of Dickens’s novels for the rest of his life.

Dickens’s next novel, David Copperfield (18491850), combined broad social perspective with an effort to take stock of himself at the midpoint of his literary career. This autobiographical novel fictionalized elements of Dickens’s childhood degradation, pursuit of a journalistic and literary vocation, and love life. It shows the first comprehensive record of the typical course of a young man’s life in Victorian England.

In 1850 Dickens began to edit a new periodical, Household Words. His editorials and articles for this magazine cover the entire span of English politics, social institutions, and family life. The weekly magazine was a great success and ran to 1859, when Dickens began to conduct a new weekly, All the Year Round. He published some of his major novels in both these periodicals.

‘‘Dark’’ Novels

In 1851 Dickens was stricken by the death of his father and one of his daughters within two weeks. Partly in response to these losses, he embarked on a series of works that have come to be called his ‘‘dark’’ novels. The first of these, Bleak House (1852-1853), has perhaps the most complicated plot of any English novel, but the narrative twists create a sense of the interrelationship of all segments of English society. The novel offers a humbling lesson about social snobbery and personal selfishness.

Dickens’s next novel is even more didactic in its criticism of selfishness. Hard Times (1854) was written specifically to challenge the common view that practicality and facts were of greater importance and value than feelings and persons. In his indignation at callousness in business and public educational systems, Dickens laid part of the charge for the heartlessness of Englishmen at the door of the utilitarian philosophy then much in vogue. This philosophy held that the moral worth of an action is defined by how it contributes to overall usefulness. But the lasting applicability of the novel lies in its intensely focused picture of an English industrial town in the heyday of capitalist expansion and in its keen view of the limitations of both employers and reformers.

The somber tone of Bleak House and Hard Times reflected the harsh social reality of an England infatuated with industrial progress at any price. Ironically, many of the societal ills that Dickens wrote about in such novels had already been righted by the time of their publication.

Some claim Little Dorrit (1855-1857) is Dickens’s greatest novel. In it he provides the same range of social observation he had developed in previous major works, but he creates two striking symbols as well. Dickens sums up the condition of England both specifically in the symbol of the debtors’ prison, in which the heroine’s father is entombed, and also generally in the many forms of personal servitude and confinement that are exhibited in the course of the plot. Second, Dickens raises to symbolic stature the child as innocent sufferer of the world’s abuses. By making his heroine not a child but a childlike figure of Christian loving kindness, Dickens poses the central question of his work—the conflict between the world’s harshness and human values.

The year 1857 saw the beginnings of a personal crisis for Dickens when he fell in love with an actress named Ellen Ternan. He separated from his wife the following year, after many years of marital incompatibility. In this period Dickens also began to give much of his time and energy to public readings from his novels, which became even more popular than his lectures on topical questions.

Later Works

In 1859 Dickens published A Tale of Two Cities, a historical novel of the French Revolution. While below the standard of the long and comprehensive ‘‘dark’’ novels, it evokes the historical period and tells of a surprisingly modern hero’s self-sacrifice. Besides publishing this novel in the newly founded All the Year Round, Dickens also published seventeen articles, which appeared in 1860 as the book The Uncommercial Traveller.

Dickens’s next novel, Great Expectations (18601861), tells the story of a young man’s moral development in the course of his life—from childhood in the provinces to gentleman’s status in London. Not an autobiographical novel like David Copperfield, Great Expectations belongs to the type of fiction called, in German, Bildungsroman (the novel of someone’s education or formation by experience).

The next work in the Dickens canon took an unusual three years to write, but in 1864-1865 Dickens published Our Mutual Friend. In it, the novelist thoroughly and devastatingly presents the vision of English society in all its classes and institutions.

In the closing years of his life, Dickens worsened his declining health by giving numerous readings. He never fully recovered from an 1865 railroad accident, but insisted on traveling throughout the British Isles and America to read before wildly enthusiastic audiences. He broke down in 1869 and gave a final series of readings in London in the following year. He also began The Mystery of Edwin Drood but died in 1870, leaving it unfinished. His burial in Westminster Abbey was an occasion of national mourning. His tombstone reads: ‘‘He was a sympathiser with the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England’s greatest writers is lost to the world.’’

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Dickens's famous contemporaries include:

Florence Nightingale (1820-1910): Born in Italy, this Englishwoman was a nursing pioneer who headed a volunteer nursing staff during the Crimean War and worked for more sanitary living conditions. She was awarded the Order of Merit in 1907.

Mark Twain (1835-1910): American writer, humorist, and satirist.

Louis Daguerre (1787-1851): French artist who invented an early form of photography, the daugerrotype.

Honore de Balzac (1799-1850): French novelist and playwright. He is regarded as one of the founders of the realist school of literature.

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910): Russian novelist and philosopher. He is one of the masters of realist fiction.

Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898): Prime minister of Prussia and later chancellor of the German empire. As chancellor, von Bismarck promoted anti-Catholic and anti-Polish sentiment but also pushed through a federal old-age pension and an accident insurance plan.

Works in Literary Context

Charles Dickens’s death on June 9, 1870, reverberated across the Atlantic, causing the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to say that he had never known ‘‘an author’s death to cause such general mourning.’’ English novelist Thomas Carlyle wrote: ‘‘It is an event world-wide, a unique of talents suddenly extinct.’’ And the day after his death, the newspaper Dickens once edited, the London Daily News, reported that Dickens had been ‘‘emphatically the novelist of his age. In his pictures of contemporary life posterity will read, more clearly than in contemporary records, the character of nineteenth century life.’’

Oliver Twist. With Oliver Twist, Dickens chose to write a kind of novel that was already highly popular, the so-called Newgate novel, named after London’s well-known Newgate prison. Two previous stories of crime and punishment had been Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Paul Clifford (1830) and Harrison Ainsworth’s Rook- wood (1834). Inevitably, Dickens did lose some readers who found the criminal aspect to be ‘‘painful and revolting,’’ as one said. A different kind of reader was put off by the prominence of the social criticism in the opening chapters, in which Dickens exposes the cruel inadequacies of workhouse life as organized by the New Poor Law of 1834. The law made the workhouses, where people who could not support themselves were forced to live and work, essentially prisons with degrading conditions, and mandated the separation of families upon entering.

Bleak House. This work boils with discontents sometimes expressed in fiery abuse, discontents that are also prominent in other Dickens novels of the 1850s and 1860s. What is strange about the chronology is that the 1850s and 1860s, economically and in other areas, were not a dark period, but rather decades when the English seemed at last to have solved some of the big problems that had looked to be insoluble in the 1830s and 1840s.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Themes of social injustice usually result from the author's own experiences or observations and most often reflect the author's dissatisfaction with the way a certain class or group is treated. Here are some works that deal with issues of social injustice.

Nickel and Dimed (2001), a nonfiction book by Barbara Ehrenreich. This memoir provides an account of the author's attempt to live off minimum-wage earnings in various U.S. states in 1998.

The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894), a nonfiction work by Leo Tolstoy. This work by the Russian novelist argues that nonviolence is the only answer to oppression. It was a major influence on the thinking of Indian activist Mohandas Gandhi.

To Sir, with Love (1959), a novel by E. R. Braithwaite. This semiautobiographical novel tells of a black teacher from Guyana and his working-class white students in a poor neighborhood of London.

Black Beauty (1877), a novel by Anna Sewell. This novel exposes the hardship and mistreatment during the life of a horse in Victorian England.

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2000), by J. K. Rowling. In the fourth installment in the Harry Potter series, Hermione Granger takes up the cause of rights for the oppressed house-elves, forming the Society for the Promotion of Elfish Welfare, to the dismay of her friends.

Works in Critical Context

Dickens preferred to write as an angry outsider, critical of the shortcomings of mid-Victorian values. Predictably, his ‘‘dark period’’ novels cost him some readers who felt that the attacks on institutions were misguided, unfair, and finally, tiresome. Obviously, not all of Dickens’s contemporaries felt the same, for among the reading public, from Bleak House onward, his novels fared well, as they have continued to do. In fact, these are the novels that have been chiefly responsible for the remarkable ‘‘Dickens boom,’’ as author Hillis Miller called it, of the 1960s and after.

Oliver Twist

The English critic and writer Angus Wilson noted that ‘‘perhaps more than any other,’’ Oliver Twist ‘‘has a combination of sensationalism and sentiment that fixes it as one of the masterpieces of pop art.’’ Critics of the day, such as that at the Quarterly Review, were quick to point out that Dickens dealt in hyperbole: ‘‘Oliver Twist is directed against the poor-law and workhouse system, and in our opinion with much unfairness. The abuses which [Dickens] ridicules are not only exaggerated, but in nineteen cases out of twenty do not exist at all.’’ Jack Lindsay in Charles Dickens: A Biographical and Critical Study wrote that ‘‘the last word ... must be given to Dickens’s power to draw characters in a method of intense poetic simplification, which makes them simultaneously social emblems, emotional symbols, and visually precise individuals.’’ The book is also one of the more enduring classics of the Dickens canon, immortalized both by its 1948 film adaptation and the 1968 musical comedy Oliver!.

Great Expectations

Many Victorian readers welcomed this novel for its humor after the ‘‘dark period’’ novels. But most critical discussions since 1950 argue that the Victorians were misled by some of its great comic scenes and also by Pip’s career. Unlike the Victorians, modern critics see Great Expectations as a brilliant study of guilt, another very sad book—another ‘‘dark period’’ novel, that is. Dickens, author Philip Hobsbaum noted, ‘‘warns us to put no trust in the surface of illusions or class and caste. Our basic personality is shaped in youth and can never change... . Every hope of altering his condition that Pip, the central character, ever entertained is smashed over his head.’’

Responses to Literature

1. The idea of childhood as a formative period is relatively modern. In the Victorian era and before, children were thought of as mini versions of adults and were expected to behave as such. Do you think that the relative freedom you have as a teenager helps you develop your strengths and sense of self, or does it encourage irresponsible behavior?

2. Using the Internet and library sources, research utilitarianism. On what basis do you think actions should be judged? Is the good of society more important than the happiness of specific individuals?

3. Dickens was deeply ashamed of his father’s time in debtor’s prison, but transformed it through his art. Using your library’s resources and the Internet, research the concept of ‘‘psychological resilience,’’ the ability to recover from difficult experiences. Write an essay outlining how a person can become more resilient, using specific examples of situations that you may have experienced yourself.

4. The Victorians believed that owing money and being unable to pay it was a moral failing. Research the current mortgage crisis in the United States, and write an essay examining modern-day attitudes toward owing money. Is owing money still seen as a moral issue, or just bad luck? Where do you think personal responsibility lies?

5. Nike was one of several companies whose manufacturers were exposed as using child labor in 2001. Nike has since changed their labor practices. Research what changes they have made, and write an essay analyzing whether they have done enough to ensure that their products do not result from exploitative labor practices. Where should a company’s standards lie—with the countries that produce its products, which might have laxer regulations, or with the country it is based in, which might result in more expensive products?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Hobsbaum, Philip. A Reader’s Guide to Charles Dickens. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1972.

House, Humphry. The Dickens World. London: Oxford University Press, 1941; 2nd ed. 1950.

Johnson, Edgar. Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph. New York: Viking, 1977.

Leavis, F. R., and Q. D. Leavis. Dickens the Novelist. London: Chatto & Windus, 1970.

Lindsay, Jack. ‘‘At Closer Grips,’’ Charles Dickens: A Biographical and Critical Study. New York: Philosophical Library, 1950.

Marcus, Stephen. Dickens from Pickwick to Dombey. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1965.

Miller, J. Hillis. Charles Dickens: The World of His Novels. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Murch, A. E. The Development of the Detective Novel. London: Owen, 1958; New York: Philosophical Library, 1958.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. Oxford Reader’s Companion to Dickens. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Sucksmith, Harvey Peter. The Narrative Art of Charles Dickens: The Rhetoric of Sympathy and Irony in His Novels. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Trilling, Lionel. The Opposing Self: Nine Essays in Criticism. New York: Viking, 1955.

Wilson, Angus. The World of Charles Dickens. New York: Viking, 1970.

Periodicals

Smiley, Jane. ‘‘Review of Charles Dickens.’’ Kirkus Reviews 70, no. 6 (2002): 395.