World Literature

Cyprian Ekwensi

BORN: 1921, Minna, Nigeria

DIED: 2007, Enugu, Nigeria

NATIONALITY: Nigerian

GENRE: Fiction

MAJOR WORKS:

People of the City (1954)

Jagua Nana (1961)

Burning Grass (1961)

Divided We Stand (1981)

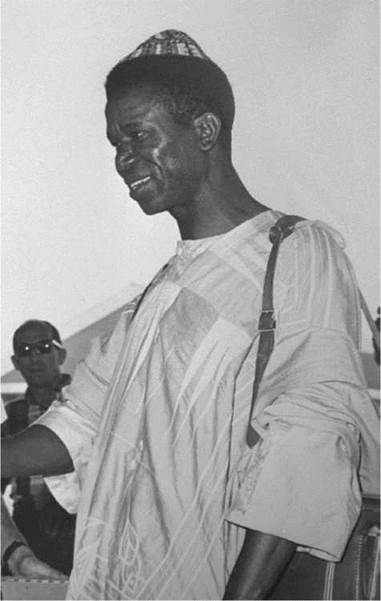

Cyprian Ekwenski. Ekwenski, Cyprian, photograph. The Library of Congress.

Overview

Cyprian Ekwensi is regarded as the father of the modern Nigerian novel. Although he wrote for both children and adults, he is especially well known for his stories for young people.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

The Nigeria of Ekwensi’s Youth. Born in Northern Nigeria in 1921, Ekwensi grew up in various cities and had numerous opportunities to observe the ‘‘urban politics’’ of Nigeria. The region had been designated as a British protectorate in 1901, and the culture quickly became a mix of traditional African and modern European influences; this mix was not always harmonious, and throughout the first half of the twentieth century, many Nigerians called for independence from England. Ekwensi received his secondary education at the Higher College in Yaba and in Ibadan at Government College, his postsecondary education at Achimota College in Ghana, the School of Forestry in Ibadan, and the Chelsea School of Pharmacy at London University. In the early 1940s, Ekwensi taught English, biology, and chemistry at Igbobi College near Lagos. Ekwensi began writing at the end of World War II. His first stories were about his father, eulogizing his unequaled bravery as an adventurous elephant hunter and his skill as a carpenter. Ekwensi’s first collection of short stories, Ikolo the Wrestler, and Other Ibo Tales, was published in 1947. In 1949 he accepted a teaching position at the Lagos School of Pharmacy.

Government Positions and Civil Strife. Despite his professional qualifications in pharmacy, Ekwensi joined the news media in 1951, working for the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. That same years Ekwensi won a government scholarship for further studies in pharmacy at London University. It was on the ship that took him from Nigeria to England that Ekwensi wrote People of the City, uniting those stories he had broadcast on Radio Nigeria into one long story. At the end of the fourteen days during which Ekwensi had secluded himself inside his cabin on the ship, he had completed his first major literary creation. Originally entitled Lajide of Lagos, Andrew Dakers published it as People of the City in 1954. In addition to being Ekwensi’s first major novel, People of the City has the distinction of being the first West African English novel written in a modern style.

Nigerian Independence. Nigeria fially gained its independence in 1960, and in 1961 Ekwensi was named federal director of information—a position in which he controlled all Nigerian media, including film, radio, television, printing, newspapers, and public relations. In that same year, he published Jagua Nana, his most popular novel. In 1967 he joined the Biafran secession as the chairman of the Bureau for External Publicity and director of BiafTa Radio. The Biafran secession occurred when an eastern region of the country dominated by the Igbo people, who experienced much persecution at the hands of other ethnic groups in the country, declared the area of BiafTa as an independent state. This led to a civil war that lasted until 1970 and resulted in the defeat of the Igbo secessionists.

Throughout his career, Ekwensi pursued his diverse vocational interests: teacher, journalist, pharmacist, diplomat, businessman, company director, public relations consultant, photographer, artist, information consultant, writer, and general shaper of public opinion. In 1991 he was appointed chairman of the Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria. Ekwensi published many more books, including a sequel to Jagua Nana called Jagua Nana’s Daughter in 1993. He became a member of the Nigerian Academy of Letters in 2006 and died of undisclosed illness in 2007.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Ekwensi's famous contemporaries include:

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992): This Russian-born author wrote a great number of science fiction novels.

Arthur C. Clarke (1917-): This British science fiction author collaborated with Stanley Kubrick on the immensely popular film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Chinua Achebe (1930-): Nigerian novelist whose English-language novel Things Fall Apart is the most widely read work of African literature ever written.

Thea Astley (1925-2004): This Australian novelist won one of her nation's major literary awards, the Miles Franklin Award, repeatedly.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Because race and politics in Africa are oftentimes difficult to separate from one another, the political and social situation in Africa has been scrutinized not only by political analysts and ethnographers around the world, but also by writers and artists. Here are a few works that explore such conflict:

Heart of Darkness (1902), a novel by Joseph Conrad. Describing the colonization of the Congo in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Conrad's work focuses on the oppression of the natives by a Belgian trading company intent on extracting and selling the resources of the Congo.

Disgrace (1999), a novel by J. M. Coetzee. This novel takes place just after an effort at racial subjugation in South Africa had ended; in order to survive in a country where black and white people are now considered equal, the white protagonist must unlearn the sexual and racial superiority he has formerly known.

Catch a Fire (2006), a film directed by Philip Noyce. Based on a true story, Patrick Chamusso, a black South African living under a racist government, turns to terrorism when he is falsely convicted of a crime.

Works in Literary Context

Ekwensi’s novels are marked by their faithfulness to realism. Influenced by his time as a radio broadcaster, his works often portray the grit and grime of city life—full as it is of excitement as well as frustration—right along with political and social commentary. As such, Ekwensi’s novels do for Africa—Lagos, in particular—what Dostoevsky did for St. Petersburg with his unflinching representation of that town’s underbelly. Ultimately, though, Ekwensi will be remembered for popularizing the novel form in Africa and helping shape the art form to make it fit Africa’s cultures and languages.

City Life Captured. With the exception of Burning Grass and Survive the Peace (1976), all of Ekwensi’s novels are set in the city of Lagos. He revels in the excitement of city life and loves to expose its many faces of modernity. Ekwensi writes about cultural centers, department stores, beaches, lagoons, political organizations and campaigns. He also writes about people in the city: criminals, prostitutes, band leaders, ministers of state, businessmen, civil servants, policemen, thugs, thieves, and many others. Authors such as J. M. Coetzee and Chinua Achebe have also written about the racial and political turmoil of the continent; Ekwensi, however, focuses his attention on the contemporary scene instead of Africa’s pre-colonial past. Using a naturalistic narrative technique reminiscent of (Emile Zola, Ekwensi captures both the restless excitement and the dissatisfaction of life in the city. Many of the incidents in his novels are taken from the everyday life around him because he believes that the function of a novelist is to reflect the social scene as faithfully as possible.

Ekwensi’s novels trace the history of Nigeria in chronological sequence. People of the City is set in the last days of the colonial era. Next is Jagua Nana, which covers the period of the election campaigns that ushered in the first independent government. Beautiful Feathers (1963) reflects the first optimistic years of independence with its concern for Pan-Africanism, the unity and cooperation of all African citizens. Iska (1966) exposes the tribal and factional divisions and animosities that finally erupted in the Nigerian civil war. Last is Survive the Peace, which begins at the end of the war and deals with the immediate problems of security and rehabilitation.

Contribution to African Literature. Ekwensi’s greatest contribution to Nigerian literature is undoubtedly his success as a social realist and a commentator on current events. Jagua Nana was one of the first novels to expose the corruption within the Nigerian political system, while Iska forecasted a civil war in Nigeria. Survive the Peace, a postwar novel, drew timely attention to refugee problems, the tragic fate of scattered families, and the fragility of peace. Divided We Stand was one of the first fictional documentaries on the war and its aftermath, and For a Roll of Parchment was one of the earliest exposes of the indignities suffered by African students in England. Ekwensi’s choice of topical subjects only added to his unrivaled popularity.

Works in Critical Context

Ekwensi’s value in paving the way for other African novelists is undisputable. The quality of his writing, however, has been the source of much debate from the beginning of his career. People of the City, which established Ekwen- si’s basic format for his novels, has been criticized for its careless plotting and its disregard for the humanity of some of its characters, who are often unceremoniously and unnecessarily killed. Because Ekwensi’s Jagua Nana frankly depicts the sexual appetite of its leading character, it has drawn the anger of many critics and moralists since its publication.

People of the City. Ekwensi knows Lagos, the setting of People of the City, very well. He also is aware of the idiosyncrasies of his characters, who are symptomatic of the city’s moral depravity. The novel’s strength is in its lifelike description of urban realities in Africa. Ekwensi ponders why things happen the way they do and why no one seems to care—or care enough. He attempts to confront society with its evils. The picture is one of squalor, bribery, corruption, and mercenary values presented by a person who has inside knowledge of the situation. In the end, it is the city that emerges as the villain: ‘‘The city eats many an innocent life every year.’’ Ekwensi’s didacticism and sense of retribution are evident throughout People of the City. Often he oversteps his role of mirroring society to that of judging it. Ekwensi is both the plaintiff and jury, and he sometimes resolves conflicts in the novel by simply killing off characters for whom he has no more use. These methods lead to melodramatic, unconvincing contrivances. Unresolved issues at the conclusion of each subplot make the novel read like day-to-day records of events that are sometimes interconnected but, more often than not, these loose ends seem haphazardly thrown together. Nonetheless, People of the City, as the first modern West African novel in English, remains of major importance. It is the picture of Lagos in all its squalor—the infectious corruption, the grab-and- keep mania—that confirms its lasting value as a work of fiction.

Jagua Nana. Ekwensi’s second major urban novel, Jagua Nana, is remarkable in many ways and has drawn conflicting responses from critics. To many, it is a masterpiece and may well be his most lasting contribution to the art of the African novel. Certainly it is his most popular novel. To some, however, all the praise the novel has attracted is misplaced and misdirected because its value as a work of art is questionable. Published a year after Nigerian independence, some church organizations and women’s unions attacked the novel and demanded that it be banned from circulation among the young. Even the Nigerian parliament was involved in the controversy. Before finally rejecting the idea, parliament debated several times a proposed filming of the novel in Nigeria by an Italian company. At the center of the whole controversy was Jagua, the heroine of the novel, whose uninhibited sexual life was said to have turned the novel into a mere exercise in pornography. Admirers of the novel, however, have described Jagua as Ekwensi’s most fully realized character and one of the most memorable heroines in fiction anywhere.

Responses to Literature

1. Jagua Nana was quite the scandal when it was published in 1961 because of its provocative sexual material. Locate summaries of the novel that give you an idea of Jagua’s lifestyle. Do you think the novel would be considered so scandalous if it had been released in the twenty-first century instead? Why or why not?

2. Read People of the City and Chinua Achebe’s Things Pall Apart. Ekwensi’s novel focuses on the city, while Achebe’s text is decidedly rural. In a short essay, compare the impressions you get about Africa based on these different representations.

3. Some critics have suggested that Ekwensi’s sense of humor is ‘‘Rabelaisian.’’ Research this word. To what extent and in what ways do you think the term applies to Ekwensi’s sense of humor, if at all?

4. J. M. Coetzee is a white South African, while Ekwensi is a Nigerian. Both are African novelists, though. Compare their representations of Africa. Based on your readings of these novelists, how do you think race—and racism, for that matter—plays into their portrayals of Africa?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Balogun, F. Odun. Tradition and Modernity in the African Short Story: An Introduction to a Literature in Search of Critics. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1991.

Bock, Hedwig and Albert Wertheim, eds. Essays on Contemporary Post-Colonial Fiction. Munich: Hueber, 1986.

Emenyonu, Ernest. Cyprian Ekwensi. London: Evans, 1974.

Nichols, Lee, ed. Conversations with African Writers: Interviews with Twenty-Six African Authors. Washington, D.C.: Voice of America, 1981.

Periodicals

Cosentino, Donald. ‘‘Jagua Nana: Culture Heroine.’’ Ba Shiru (1977).

Echeruo, Michael J. C. ‘‘The Fiction of Cyprian Ekwensi.’’ Nigeria Magazine (1962).

Lindfors, Bernth. ‘‘Interview with Cyprian Ekwensi.’’ World Literature Written in English (1974).

Hawkins, Loretta A. ‘‘The Free Spirit of Ekwensi’s Jagua Nana.’’ African Literature Today (1979).