World Literature

Kahlil Gibran

BORN: 1883, Bechari, Lebanon

DIED: 1931, New York

NATIONALITY: Lebanese

GENRE: Poetry

MAJOR WORKS:

A Tear and a Smile (1914)

The Madman (1918)

The Prophet (1923)

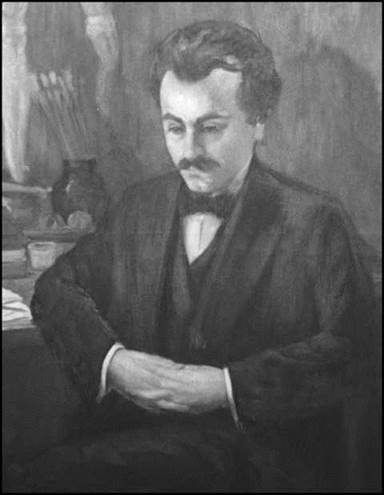

Kahlil Gibran. © Helene Rogers / Alamy

Overview

Lebanese author of the immensely popular The Prophet, Kahlil Gibran is one of the most commercially successful poets of the twentieth century. His small books, biblical in style and often illustrated with his own allegorical drawings, have been translated into twenty languages, making him the most widely known writer to emerge from the Arab-speaking world. Gibran’s poetry and prose are recognized for their metrical beauty and emotionally evocative language. They also demonstrate an ecstatic spiritualism and a serene love of humanity.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

From Lebanon to the United States and Back. Kahlil Gibran, baptized Gibran Khalil Gibran, was born on January 6, 1883, in Bechari, Lebanon, to Khalil Gibran and Kamila Rahme. His childhood in the isolated village beneath Mt. Lebanon included few material comforts, and he had no formal early education. However, he received a strong spiritual heritage. From an early age he displayed a range of artistic skills, especially in the visual arts. He continued to draw and paint throughout his life, even illustrating many of his books. Gibran’s family immigrated to the United States when he was twelve and settled in the Boston area, but he returned to the Middle East for schooling two years later. Pursuing his artistic talents further, he entered the famed Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, where he studied under the French sculptor Auguste Rodin. Gibran’s first efforts at writing were poems and short plays originally penned in Arabic that attracted modest success. In 1904, Gibran returned to the United States where he befriended Mary Haskell, headmistress of a Boston school. She became his adviser, and the two wrote lengthy romantic missives to each other for a number of years. These letters were later reproduced in the 1972 book Beloved Prophet: The Love Letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell, and Her Private Journal.

Exile and World War I. During these early adult years, Gibran lived in Boston’s Chinatown. Scholars note that the works from this period show a preoccupation with his homeland and a sadness stemming from his status as an exile. One of his first published books, ‘Ar’ is al-muruj (later published in English as Nymphs of the Valley, 1910), was a collection of three stories set in Lebanon. Two subsequent works written during this era, later published as Spirits Rebellious and The Broken Wings, are, respectively, a collection of four stories and one novella. in each, a young man is the hero figure, rebelling against those inside Lebanon who are corrupting it; common literary targets include the Lebanese aristocracy and the Christian church.

During world war i, his growing success as an emigre writer was tempered by Lebanon’s abysmal wartime situation. Lebanon was at the time a region of the Ottoman Empire, which had chosen to side with Germany and Austro-Hungary, the Central powers, in their war against England, France, Russia, and their allies. Ultimately, after the Central powers were defeated by Allied troops, the Ottoman Empire was occupied and broken up into smaller regions to be controlled by Allied countries; as part of the peace accord, France assumed control of Lebanon. Prior to that, however, during the harshest periods of the war, many Lebanese citizens starved to death. Scholars of the poet’s body of work hypothesize that Gibran’s sorrow manifested itself in a more pronounced quest for self-fulfillment in his works, and a spirituality that sought wisdom and truth without the aid of an organized religion. At one point in his career, the writer was excommunicated from the Christian Maronite church. His first work written and published in English was 1918’s The Madman: His Parables and Poems. Its title comes from a previously published prose work in which the hero sees existence as ‘‘a tower whose bottom is the earth and whose top is the world of the infinite ... to clamour for the infinite in one’s life is to be considered an outcast and a fool by the rest of men clinging to the bottom of the tower,’’ explained Mikhail Naimy in the Journal of Arabic Literature.

Out of the sadness and despair of the years leading up to, including, and following World War I came Gibran’s best-known work, The Prophet, which was published in 1923. The author planned it to be first in a trilogy, followed by The Garden of the Prophet and The Death of the Prophet. The initial book The Prophet chronicles, through the title character Almustafa’s own sermons, his life and teachings. Much of it is given in orations to the Orphalese, the people among whom Almustafa has been placed.

Death. Gibran was forty-eight when he died of liver cancer in New York City on April 10, 1931. The Arabic world eulogized him as a genius and patriot. A grand procession greeted his body upon its return to Bechari for burial in September 1931.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Gibran's famous contemporaries include:

Mohandas Gandhi (1869-1948): This Indian social leader advocated nonviolent resistance as a means to effect social change.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945): The thirty- second president of the United States served four terms in office. His New Deal policies are widely credited with helping the United States survive the Great Depression.

T. S. Eliot (1888-1965): American-born expatriate poet and playwright. His best-known poem, The Waste Land, was published the year before Gibran's The Prophet.

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919): Nicknamed Teddy, he was the twenty-sixth president of the United States, serving in office from 1901 to 1909.

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939): This Irish poet was honored with the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1923, the year of the publication of Gibran's The Prophet.

Works in Literary Context

Diverse influences, including Boston’s literary world, the English Romantic poets, mystic William Blake, and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, combined with his Bechari experience, shaped Gibran’s artistic and literary career. The influence of English poet William Blake, who illustrated his own collections of poetry, can be seen in Gibran’s own illustrations. However, the most fruitful analysis of Gibran’s predecessors must include a look at the parallels between Gibran’s magnum opus and nineteenth-century authors Nietzsche and Walt Whitman.

Literary Comparisons. Gibran’s biographer, Mikhail Naimy, found similarities between The Prophet and Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra. In each, the author speaks through a created diviner and both prophets walk among humankind as outsiders. Some elements are autobiographical. The critic saw a parallel in Gibran’s dozen-year stay in New York City with the twelve-year wait Almustafa endured before returning home from the land of the Orphalese.

Another critic compared The Prophet to Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself. Mysticism, asserted Suhail ibn-Salim Hanna in Literature East and West, is a theme common to both, with Gibran having rejected the attitudes termed Nietzschean in favor of the more benign European ideology that unfolded during the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. ‘‘Like Whitman, Gibran came to see, even accept, the reality of a benevolent and harmonious universe,’’ wrote Hanna.

Gibran’s Legacy. Authors since Gibran have utilized the spiritual/mystical autobiographical form to great effect. Respected psychiatrist Carl Jung took the form, tweaked it, and produced his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Nonetheless, Gibran’s legacy extends beyond his direct influence on his literary successors and is best seen in the way he is viewed as an inspirational figure, whose mere mention evokes mysticism and thoughtfulness.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Gibran's early work demonstrates his feeling of exile from his native Lebanon, suffusing it with great sadness and inspiring brilliance. Here are a few of the works of exiled writers:

Tristia (c. 10 CE), a work of poetry by Ovid. Ovid was exiled by the Roman emperor Augustus for reasons that remain mysterious. In this work, he laments his exiled state.

Dubliners (1914), a book of short stories by James Joyce. This collection of short stories depicts the people and places of Dublin. The book was well received by the Irish, many of whom felt that Joyce had captured the essence of the Irish character, both good and bad. The collection was published ten years after Joyce subjected himself to a self-imposed exile from his native Ireland.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1982), a novel by Milan Kundera. Czech author Kundera lived in exile in Paris while his homeland was dominated by the Soviet Union, and wrote this novel about the Prague Spring, a period of political liberalization that led to a Soviet military crackdown in 1968.

Works in Critical Context

Overall, Gibran’s work has received little academic examination. As an introductory essay in Twentieth Century Literary Criticism points out, ‘‘Generally, most critics agree that Gibran had the refined sensibility of a true poet and a gift for language, but that he often marred his work by relying on shallow epigrams and trite parables.’’

A Tear and a Smile. Gibran’s first collection of poetry appeared in Arabic in 1914 and was translated into English several years later and published as A Tear and a Smile. ‘‘The tears, which are much more abundant here than the smiles,’’ observed N. Naimy in Journal of Arabic Literature, ‘‘are those of Gibran the misfit rather than of the rebel in Boston, singing in an exceedingly touching way of his frustrated love and estrangement, his loneliness, homesickness and melancholy.’’ Naimy called this book a bridge between a first and second stage of Gibran’s career: the writer’s longing for Lebanon gradually evolved into a dissatisfaction with the destructive attitude of humankind in general. By now Gibran’s body of work was received enthusiastically in the extensive Arabic-speaking world, winning a readership that stretched from Asia to the Middle East to Europe, as well as across the Atlantic. Soon his writings were being referred to as ‘‘Gibranism,’’ a concept that ‘‘Gibran’s English readers will have no difficulty in divining,’’ wrote Claude Bragdon in his book Merely Players; aspects of ‘‘Gibranism’’ include ‘‘Mystical vision, metrical beauty, a simple and fresh approach to the so-called problems of life.’’ Today, Arabic scholars praise Gibran for introducing Western romanticism and a freer style to highly formalized Arabic poetry.

The Prophet In October 1923 The Prophet was published; it sold over one thousand copies in three months. The Prophet was a popular success, but its critical reception has always been mixed. ‘‘In this book, more than in any other of his books, Gibran’s style reaches its very zenith,’’ declared Gibran’s biographer, Mikhail Naimy. ‘‘Many metaphors are so deftly formed that they stand out like statues chiseled in the rock.’’ Nonetheless, not all critics were as kind to Gibran’s magnum opus as Naimy. Critiquing The Prophet from a more practical standpoint, Gibran’s biographer, Khalil S. Hawi, faulted its structure. Writing in Kahlil Gibran: His Background, Character and Works, Hawi noted that ‘‘behind the attempts to perfect the sermons and each epigrammatical sentence in them lies an artistic carelessness which allowed him to leave the Prophet standing on his feet from morning to evening delivering sermon after sermon, without pausing to consider that the old man might get tired, or that his audience might not be able to concentrate on his sermons for so long.’’ Still, The Prophet went on to become the best-selling title in the history of its publisher, Alfred A. Knopf.

Responses to Literature

1. Using the Internet and the library, research the word mystic. Based on your research, would you consider Kahlil Gibran a mystic? Why or why not? Explain your thinking in a short essay.

2. For a long time, mystics were popular religious leaders. In some ways, some very important historical figures could be considered mystics: Jesus Christ, Confucius, Buddha, and even Socrates. How do you think mystics would be received today?

3. Read The Prophet, keeping in mind Khalil Hawi’s criticism of the practicality of the Prophet’s delivering sermon after sermon without pausing. Do you think that Hawi’s criticism is justified? If so, do you think the criticism lessens the overall effect of the text? Explain your thought processes in a short essay.

4. In what ways, if at all, is the teaching of the Prophet in The Prophet relevant to your life? Cite specific examples from the text as you fashion your response.

5. To find out more about the history of Lebanon, read A House of Many Mansions: A History of Lebanon Reconsidered (1993), by Kamal Salibi. Salibi has been praised for his even-handed approach to Lebanon’s recent history, which is marked by sectarian violence.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Bragdon, Claude. Merely Players. New York: Knopf, 1929.

Gibbon, Monk, ed. The Living Torch. New York: Macmillan, 1938.

Gibran, Jean. Kahlil Gibran, His Life and World. New York: Interlink Books, 1991.

Hawi, Khalil. Kahlil Gibran: His Background, Character, and Works. Beirut: American University. 1963.

________. Kahlil Gibran: His Background, Character and Works. Beirut: Arab Institute for Research and Publishing, 1972.

Hilu, Virginia, ed. Beloved Prophet: The Love Letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell, and Her Private Journal. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1972.

Naimy, Mikhail. Kahlil Gibran: A Biography. New York: Philosophical Library, 1934.