World Literature

William Golding

BORN: 1911, St. Columb, England

DIED: 1993, Perranarworthal, England

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Fiction

MAJOR WORKS:

Lord of the Flies (1954)

Darkness Visible (1979)

Rites of Passage (1980)

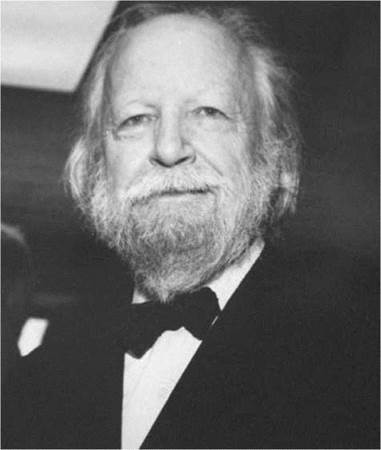

William Golding. Golding, William, photograph. The Library of Congress.

Overview

William Golding was a British novelist, poet, and Nobel Prize laureate. With the appearance of Lord of the Flies (1954), Golding’s first published novel, the author began his career as both a campus cult favorite and one of the most distinctive and debated literary talents of his era. The author’s prolific output—five novels in ten years— and the high quality of his work established him as one of the late twentieth century’s most distinguished writers. He won the Booker Prize for literature in 1980 for Rites of Passage, the first book of his To the Ends of the Earth trilogy. Golding has been described as pessimistic, mythical, and spiritual—an allegorist who uses his novels as a canvas to paint portraits of man’s constant struggle between his civilized self and his hidden, darker nature.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Probing the Darkness. Golding was born in England’s west country in 1911. His father, Alex, was a follower in the family tradition of schoolmasters; his mother, Mildred, was a political activist for women getting the right to vote. The family home in Marlborough is characterized by Stephen Medcalf in William Golding as ‘‘darkness and terror made objective in the flint-walled cellars of their fourteenth-century house ... and in the graveyard by which it stood.’’ By the time Golding was seven years old, Medcalf continues, ‘‘he had begun to connect the darkness... with the ancient Egyptians. From them he learnt, or on them he projected, mystery and symbolism, a habit of mingling life and death, and an attitude of mind sceptical of the scientific method that descends from the Greeks.’’

After graduating from Oxford, Golding perpetuated family tradition by becoming a schoolmaster in Salisbury, Wiltshire. His teaching career was interrupted in 1940, however, when World War II found ‘‘Schoolie,’’ as he was called, serving five years in the Royal Navy. Lieutenant Golding saw active duty in the North Atlantic, commanding a rocket-launching craft. Present at the sinking of the Bismarck and participating in the D-Day invasion of France by Allied forces, Golding later told Joseph Wershba of the New York Post: ‘‘World War Two was the turning point for me. I began to see what people were capable of doing.’’ Indeed, the author’s anxieties about both nuclear war and the potential savagery of humankind were the basis of the novel Lord of the Flies.

Writing to Please Himself. On returning to his post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School in 1945, Golding, who had enhanced his knowledge of Greek history and mythology by reading while at sea, attempted to further his writing career. He produced three novel manuscripts that remained unpublished. ‘‘All that [the author] has divulged about these [works] is that they were attempts to please publishers and that eventually they convinced him that he should write something to please himself,’’ notes Bernard S. Oldsey. That ambition was realized in 1954, when Golding created Lord of the Flies.

For fifteen years after World War II, Golding concentrated his reading in the classical Greeks, and his viewpoint seems close to the Greek picture of humans at the mercy of powers erupting out of the darkness around and within individuals. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1983, and in his address at the awards ceremony, he said that the English language was possibly suffering from ‘‘too wide a use rather than too narrow a one.’’ Stressing the significance of stories, Golding also expressed his concern with the state of the planet and raised the question of environmental issues. He then focused on the writer’s craft, saying that words ‘‘may through the luck of writers prove to be the most powerful thing in the world.’’

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Golding's famous contemporaries include:

J. D. Salinger (1919-): A reclusive author who wrote The Catcher in the Rye (1951), a classic novel about adolescence and the painful journey to responsibility and maturity—perhaps the main rival for Lord of the Flies in high school student popularity.

Winston Churchill (1874-1965): Prime minister of Great Britain from 1940 until 1945. Churchill's inspirational speeches were perhaps just as influential as his determination and brilliant military strategies in guiding Britain and her allies to victory in World War II.

Francis Ford Coppola (1939-): American film director who is behind some of the most detailed explorations of the violent psychology that has shaped twentieth- century culture: Apocalypse Now and the trilogy of Godfather movies.

Joseph Campbell (1904-1987): An American professor who became an expert on world mythologies, demonstrating in a series of widely popular books and media presentations that the great stories and religious mythologies throughout history share a limited number of recurring patterns and powerful spiritual symbols.

Elie Wiesel (1928-): A Jewish Holocaust survivor who has written over forty novels, memoirs, and political tracts, the most famous of which is Night, his memorable account of his imprisonment in several concentration camps in Germany and Austria during World War II. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Lord of the Flies shows that when people are abandoned in a faraway place, far from traditional external authorities, their deepest nature is exposed. Here are some other works that also explore humanity's place in the wilds of the world.

Paradise Lost (1667), an epic poem by John Milton. This extended meditation on the nature of Good and Evil takes the form of an epic poem about Satan's rebellion in Heaven, his subsequent banishment to Hell, and his attempts to get revenge on God by spoiling His new creation of Adam and Eve in Paradise.

Robinson Crusoe (1719), a novel by Daniel Defoe. What started out as a fake travel narrative of a sailor marooned on a deserted island has become a classic tale of self-reliance. One of the earliest British novels, this book has helped define the British middle-class ethics of faith, self-control, and hard work ever since.

Gulliver's Travels (1726), a work of fiction by Jonathan Swift. The best known of Jonathan Swift's works, this classic of English literature is a satire on human nature and a parody of the popular travel narratives of the time. Gulliver becomes marooned in various exotic locations, and Swift uses the situations for everything from outrageous comedy to searing satire on the human condition.

Cast Away (2000), a film directed by Robert Zemeckis. This movie, starring Tom Hanks, is about a time-obsessed Federal Express systems engineer who finds himself alone on a tropical island after a plane crash.

Works in Literary Context

Savagery Versus Civilized Behavior. While the story has been compared to such previous works as Robinson Crusoe and High Wind in Jamaica, Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies is actually the author’s ‘‘answer’’ to nineteenth-century writer R. M. Ballantyne’s children’s classic The Coral Island: A Tale of the Pacific Ocean. These two books share the same basic plot line and even some of the same character names. Although some similarities exist, Lord of the Flies totally reverses Ballantyne’s concept of the purity and innocence of youth and humanity’s ability to remain civilized under the worst conditions. In Lord of the Flies, Golding presented the central theme of his collective works: the conflict between the forces of light and dark within the human soul. Although the novel did not gain popularity in the United States until several years after its original publication, it has now become a modern classic, most often studied in high schools and colleges.

Shift of Perspective. While none of Golding’s subsequent works achieved the critical success of Lord of the Flies he continued to produce novels that attracted widespread critical interpretation. Within the thematic context of exploring the depths of human depravity, the settings of Golding’s works range from the prehistoric age, as in The Inheritors (1955); to the Middle Ages, as in The Spire (1964); to contemporary English society. This wide variety of settings, tones, and structures presents dilemmas to critics attempting to categorize them. Nevertheless, certain stylistic devices are characteristic of his work. One of these, the use of a sudden shift of perspective, has been so dramatically employed by Golding that it has both enchanted and infuriated critics and readers alike. For example, Pincher Martin (1956) is the story of Christopher Martin, a naval officer who is stranded on a rock in the middle of the ocean after his ship has been torpedoed. The entire book relates Martin’s struggles to remain alive against all odds. The reader learns in the last few pages that Martin’s death occurred on the second page—a fact that transforms the novel from a struggle for earthly survival into a struggle for eternal salvation.

Morality. By 1965, Golding had produced six novels and was evidently on his way to continuing acclaim and popular acceptance—but then matters changed abruptly. The writer’s output dropped dramatically: For the next fifteen years he produced no novels and only a handful of novellas, short stories, and occasional pieces. Of this period, The Pyramid, a collection of three related novellas, is generally regarded as one of the writer’s weaker efforts. Golding’s reintroduction to the literary world was acknowledged in 1979 with the publication of Darkness Visible, the title of which derived from John Milton’s famous description of Hell in Paradise Lost. From the first scenes of the book, Golding confronts the reader with images of fire, mutilation, and pain, which he presents in biblical terms. Samuel Hynes observed in a Washington Post Book World article,

[He is] still a moralist, still a maker of parables. To be a moralist you must believe in good and evil, and Golding does; indeed, you might say that the nature of good and evil is his only theme. To be a parable-maker you must believe that moral meaning can be expressed in the very fabric of the story itself, and perhaps that some meanings can only be expressed in this way; and this, too, has always been Golding’s way.

Myth and Allegory. Golding’s novels are often termed fables or myths. They are laden with symbols (usually of a spiritual or religious nature) so imbued with meaning that they can be interpreted on many different levels. The Spire, for example, is perhaps his most polished allegorical novel, equating the erecting of a cathedral spire with the protagonist’s conflict between his religious faith and the temptations to which he is exposed.

Works in Critical Context

The novel that established Golding’s reputation, Lord of the Flies, was rejected by twenty-one publishers before Faber & Faber accepted the forty-three-year-old schoolmaster’s book. Initially, the tale of a group of schoolboys stranded on an island during their escape from atomic war received mixed reviews and sold only modestly in its hardcover edition. But when the paperback edition was published in 1959, thus making the book more accessible to students, the novel began to sell briskly. Teachers, aware of the student interest and impressed by the strong theme and stark symbolism of the work, assigned Lord of the Flies to their literature classes. And as the novel’s reputation grew, critics reacted by drawing scholarly theses out of what was previously dismissed as just another adventure story.

While he has faced extensive criticism and categorization in his writing career, the author is able to provide a brief, simple description of himself in Jack I. Biles’s Talk: Conversations with William Golding:

I’m against the picture of the artist as the starry- eyed visionary not really in control or knowing what he does. I think I’d almost prefer the word ‘craftsman.’ He’s like one of the old-fashioned shipbuilders, who conceived the boat in their mind and then, after that, touched every single piece that went into the boat. They were in complete control; they knew it inch by inch, and I think the novelist is very much like that.

Lord of the Flies. Lord of the Flies has been interpreted by some as being Golding’s response to the popular artistic notion of the 1950s that youth was a basically innocent collective and that they are the victims of adult society (as seen in J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye). In 1960, C. B. Cox deemed Lord of the Flies as ‘‘probably the most important novel to be published ... in the 1950s.’’ Cox, writing in Critical Quarterly, continued: [To] succeed, a good story needs more than sudden deaths, a terrifying chase and an unexpected conclusion. Lord of the Flies includes all these ingredients, but their exceptional force derives from Golding’s faith that every detail of human life has a religious significance. This is one reason why he is unique among new writers in the ’50s.... Golding’s intense conviction [is] that every particular of human life has a profound importance. His children are not juvenile delinquents, but human beings realising for themselves the beauty and horror of life.

Not every critic responded with admiration to Lord of the Flies, however. One of Golding’s more vocal detractors is Kenneth Rexroth, who had this to say in the Atlantic: ‘‘Golding’s novels are rigged. All thesis novels are rigged. In the great ones the drama escapes from the cage of the rigging or is acted out on it as on a skeleton stage set. Golding’s thesis requires more rigging than most and it must by definition be escape-proof and collapsing.’’ Rexroth elaborates: ‘‘[The novel] functions in a minimal ecology, but even so, and indefinite as it is, it is wrong. It’s the wrong rock for such an island and the wrong vegetation. The boys never come alive as real boys. They are simply the projected annoyances of a disgruntled English schoolmaster.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Why do you think Golding is so interested in the causes of violence and brutality? Research some of his interviews and consider his life history. Is it surprising that someone like Golding would be so involved in writing about the psychology of violence and be able to do it with such insight?

2. What exactly is the definition of a ‘‘fable,’’ and how does it apply to Lord of the Flies and Golding’s other works?

3. Many reality television shows today play on the stranded-on-a-deserted-island motif. Do you think that shows such as Survivor demonstrate the same psychology we see in Lord of the Flies? In particular, you might want to research the short-lived show Kid Nation, which put forty children from ages eight to fifteen alone together in a deserted town to see how they would manage.

4. Scientist James Lovelock is the creator of an idea known as the Gaia hypothesis; this name was recommended to him by his acquaintance, William Golding. Research the Gaia hypothesis. What are the basic ideas behind it? How did Golding’s literary preferences lead him to come up with this name? Can you find any similarities between the Gaia hypothesis and Golding’s views on humans and nature?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Babb, Howard S. The Novels of William Golding. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1970.

Biles, Jack I. Talk: Conversations with William Golding. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970.

Biles, Jack I., and Robert O. Evans, eds. William Golding: Some Critical Considerations. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1979.

Carey, John, ed. William Golding: The Man and His Books: A Tribute on His 75th Birthday. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1987.

Crompton, Don. A View from the Spire: William Golding’s Later Novels. Edited and completed by Julia Briggs. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985.

Friedman, Lawrence S. William Golding. New York: Continuum, 1993.

Reilly, Patrick. Lord of the Flies: Fathers and Sons. New York: Twayne, 1992.

Periodicals

Kermode, Frank. ‘‘The Novels of William Golding.’’ International Literary Annual 3 (1961): 11-29.

Oldsey, Bernard S., and Stanley Weintraub. ‘‘Lord of the Flies: Beelzebub Revisited.’’ College English 25 (November 1963): 90-99.

Peter, John. ‘‘The Fables of William Golding.’’ Kenyon Review 19 (1957): 577-92.

Web sites

William Golding Home Page. Retrieved March 10, 2008, from http://www.william-golding.co.uk. Last updated on March 10, 2008.