World Literature

Jose Maria Arguedas

BORN: 1911, Andahuaylas, Peru

DIED: 1969, La Molina, Peru

NATIONALITY: Peruvian

GENRE: Fiction

MAJOR WORKS:

Los nosprofundos (Deep Rivers, 1958)

Todas las sangres (All Bloods, 1964)

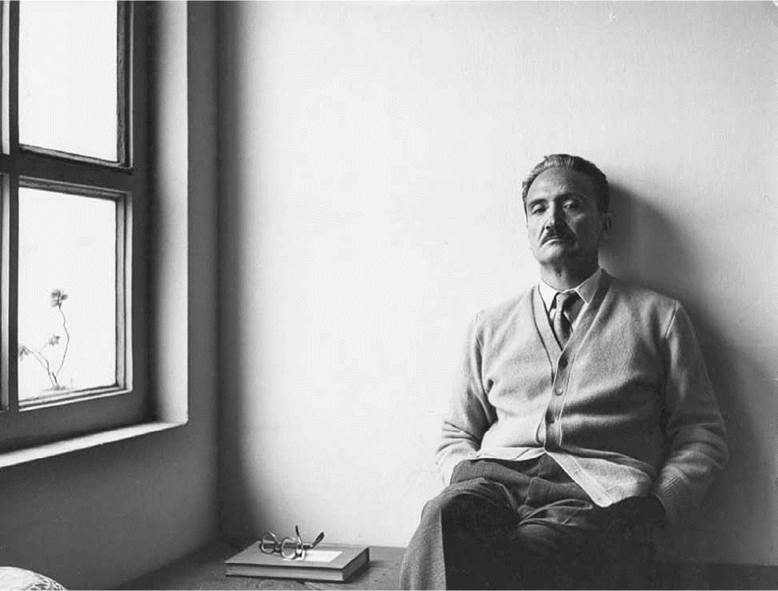

Jose Maria Arguedas. © Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru / Instituto Riva-Aguero

Overview

Jose Maria Arguedas is one of Peru’s leading novelists, along with Mario Vargas Llosa. However, while Vargas Llosa belongs to the Western mainstream, Arguedas wrote as a spokesman of the indigenous Quechua-speaking Andean world, setting out to correct the distorted, stereotyped image of the Indian presented by earlier fiction.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Remote Culture. Jose Maria Arguedas was born on January 18, 1911, in the province of Andahuaylas in the southern Peruvian Andes mountains. He was the son of Victor Manuel Arguedas Arellano, a lawyer, and Victoria Altamirano Navarro.

His birth and childhood in Andahuaylas were important to the world he created in fiction and informed his historical sense of Andean peoples. Even today, access to Andahuaylas is difficult; in the time of Arguedas’s childhood, however, the province was almost completely isolated from the outside world. Its capital city, Abancay, located on the low eastern slopes of the Andes' western chain, was then and remains today oriented toward Cuzco, the ancient center of the Incan empire.

After his mother's death and his father's remarriage, Arguedas grew up as a virtual servant in his stepmother's home. Thus, although he was non-Indian, for all practical purposes he grew up not only within the Indian culture of the house servants and field workers in the hacienda, but also as a monolingual Quechua speaker.

Merging Two Worlds. As a teenager, Arguedas began to learn Spanish as a literary and intellectual vehicle of expression. Throughout his life, however, Arguedas continued to write in Quechua in an effort to convert it into a modern literary language. As a writer, he was faced with the problem of translating into the alien medium of Spanish the sensibility of a people who express themselves in Quechua. His initial solution was to modify Spanish in such a way as to incorporate the basic features of Quechua syntax and thus reproduce something of the special character of Indian speech; but these experiments were only partially successful, and he later decided on a correct Spanish manipulated to convey Andean thought-patterns.

As a university student, Arguedas was involved with the academic and intellectual circles interested in change and social justice in Peru. His association with the emerging political-left parties landed him in jail in 1937 during the dictatorship of General Oscar Raimundo Benavides. Thanks to Arguedas’s future wife, Celia Bustamante Vernal (whom he married in 1939), and a dedicated core of friends, he was eventually freed. Arguedas soon became a full-time anthropologist, field researcher, and novelist.

Early Publications. Arguedas’s first book, Agua. Los escoleros. Warma kukay (Water. The Students. Puppy Love), usually referred to as Agua, brings together three short stories that deal with the economically exploited Indian communities. Upon its publication in 1935, it was largely ignored.

In 1941 he published his first novel, Yawar fiesta (Blood Fiesta). Diamantesy pedernales. Agua (Diamonds and Flintstones. Water, 1954) includes the contents of Agua and introduces his first and only novella, Diamantes y pedernales. His major novel, Los nos profundos (1958; translated as Deep Rivers, 1978) is widely considered his masterpiece. With its publication, Arguedas became a preeminent figure not only in Peruvian life but also among the international scholars who study Peru’s ancient and contemporary civilizations.

El sexto (The Sixth, 1961) followed, a novel about the confinement of political prisoners in the most dreaded of Peruvian prisons, El Sexto. This hallucinatory novel was followed by the story of Rasu Niti, the master scissor dancer in La agonia de ‘‘Rasu Niti” (Rasu Niti’s Agony, 1962).

Anthropological Inspiration. Arguedas was one of the first anthropologists to demonstrate the range, role, and significance of poetic composition for complex singing arrangements. He composed many short ballads and lyrics in Quechua, but perhaps his greatest poetic composition in Quechua is his Tipac Amaru Kamaq taytanchis- man; Haylli-taki. A nuestro padre creador Tupac Amaru; Himno-cancion (To Our Lord the Father-Creator Tiipac Amaru; Hymn-Song, 1962).

From 1963 until 1969, he held an important teaching position at the Universidad Nacional Agraria in La Molina. In 1963 he also became director of the Casa de la Cultura, Peru’s major institution for the organization and promotion of artistic and intellectual activity.

Todas las sangres (All Bloods), was published in 1964. In this later work, Arguedas’s interests changed from the Andean villages of Los rios profundos—set in the early 1920s before roads, cars, and trucks made communication easier among the many isolated areas of the Andean territory—to a deteriorating and partially abandoned provincial capital in Todas las sangres. As the title of the novel indicates, the plot attempts to bring together the many races (or bloods) that constitute a fragmented society caught in the corrosive process of becoming a nation. With its emphasis on modernity, Todas las sangres spells out the beginning of the end of the world of Agua. Arguedas regarded that ending with more terror than relief, for the Andean culture whose achievements and beauty he had so dexterously portrayed could no longer aspire to continue untouched if the Indians were to liberate themselves from domination.

Later Life. Arguedas often experienced intense and crippling depression. In 1966, soon after his divorce from his first wife, he attempted suicide. In 1967 he married Sybila Arredondo, a Chilean; however, in 1969, in a bathroom near his office at La Molina, he succeeded in committing suicide.

El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo (The Fox from Up Above and the Fox from Down Below, 1969) was published after Arguedas’s death. In it, Arguedas attempts to come to grips with the new world wrought in Peru by the forces of hunger, improved communications, the fast influx of foreign capital, and the contending ideologies of the time. In 1983 his widow, Sybila, with others, edited and published his Obras completas (Complete Works).

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Arguedas's famous contemporaries include:

Ruth Benedict (1887-1948): American anthropologist and proponent of cultural relativism, the theory that each culture has its own definition of right and wrong.

Pieter Botha (1916-2006): white South African prime minister (1978-1984) and president (1984-1989) who refused to abolish apartheid, the brutal state-sanctioned policy of enforced segregation of blacks and whites.

Ferruccio Lamborghini (1916-1993): Italian tractor manufacturer who founded the Lamborghini automotive brand in 1963.

Mario Vargas Llosa (1936- ): leading Peruvian writer who combines realism and experimentalism in his novels; he unsuccessfully ran for the presidency in 1990.

Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2005): Polish poet who defected to the United States in 1960; his work was banned in then-Communist Poland until he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980.

Works in Literary Context

The Complexity of Andean Society. The context of Jose Maria Arguedas’s fiction is the semifeudal socioeconomic order that prevailed in the Andean highlands from the Spanish Conquest until recent times. However, while earlier writers had depicted a black-and-white confrontation between oppressive white landowners and a downtrodden Indian peasantry, Arguedas presents a much more complex picture of Andean society. His work as an anthropologist led him to the remote Andean villages of Peru, where he collected folktales, songs, and myths. Arguedas thus was deeply aware of the Andean literary legacy in the form of legend, art, and humor.

Authentic Indian Perspective. In his search for solutions to his problem of authenticity, Arguedas searched for the means by which Spanish as a literary system would not betray the essence or the difference of what he wanted to inscribe: the Indian and his world as seen by himself. While writing Agua, he read many current Peruvian novels. He found that these texts offered a deeply false and negative view of the Indian world. Arguedas’s objective in writing fiction as well as his final choice of writing in Spanish was in part driven by the passion to correct a falsehood and the need to portray the world of his childhood. Arguedas’s reading of the works of Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky opened windows for the portrayal of the oppressed and the suffering.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Jose Maria Arguedas was part of the Indianismo movement in Latin American literature, which explored the lives of indigenous peoples. Here are some other works that examine the lives of indigenous people:

Broad and Alien Is the World (1941), a novel by Ciro Alegrla. This Peruvian novel examines the effect of land reform on the indigenous Indian communities.

The Devil to Pay in the Backlands (1956), a novel by Joao Guimaraes Rosa. In this novel, considered to be the Brazilian equivalent of James Joyce's modernist landmark Ulysses, a bandit from the Brazilian hinterlands tells his life story to a stranger.

In the Castle of My Skin (1953), a novel by George Lamming. This autobiographical novel by the Barbados writer explores the experience of growing up in a West Indian village under colonial rule.

Men of Maize (1949), a novel by Miguel Angel Asturias. This magical realist novel, by the Nobel Prize-winning Guatemalan writer, examines two views of maize: that of the indigenous people, who consider it sacred, and that of international corporations, who view it solely as a commercial staple.

Flint and Feather (1912), a poetry collection by E. Pauline Johnson. Selected poems from the Canadian First Nations poet focus on native themes and characters.

Works in Critical Context

Early in his career as an anthropologist and novelist, Arguedas spoke about the painful task of creating an imaginary world that was based on his hatred of the world order created by the masters who oppressed the Indians. Thirteen years after the publication of Agua, he said he wrote it in a fit of rage (arrebato). Such a confrontational opposition became the core of Arguedas’s plot structures. As Antonio Cornejo-Polar has shown in Los universos narrativos de Jose Maria Arguedas (1973), Arguedas’s entire fictional corpus is anchored in a play of oppositions, which develops a series of variations of ever- richer complexity.

The Fox from Up Above and the Fox from Down Below. His final book, The Fox from Up Above and the Fox from Down Below, was published posthumously to acclaim and recognition of the autobiographical nature of the work. Julio Ortega, writing for Review, described the book as ‘‘a complex and extraordinary document.’’ Ortega concluded, ‘‘Even though this novel is not, as such, on a par with his previous books, as a document it possesses a value of a different order, and its peculiar intensity and character confer upon it a heightened and deepened life.’’

Responses to Literature

1. When we read about an unfamiliar culture, how can we be sure that it is being presented accurately? What misunderstandings might this lead to?

2. Today, because of the Internet and global communications, cultural change seems to happen especially quickly. Do you think that many cultures will emerge as one larger culture as a result, or do you think people will still hold on to some of their traditional beliefs and practices? Can you apply these ideas of blending cultures to Arguedas’s later works set in cities rather than small villages?

3. Leaving behind what you know and are familiar with can be scary and intimidating. Jose Maria Arguedas went to college and became a respected author and scholar, leaving behind the Indians he grew up with and their rural culture. But he wrote about them in his novels and also in his work as an anthropologist. Think of something you are afraid of leaving behind and write a list of ways that you can keep that in your life while also moving on and growing.

4. Using your library’s resources and the Internet, research your own ethnic heritage. Write an essay analyzing how it has been presented over time and examining how and why this presentation has changed. Do you feel it is accurate as currently presented? Explain.

5. How can you express in one language the thoughts and words of speakers of a second language? Choose a hip-hop or rap song and ‘‘translate’’ it into standard English. Were you able to get across the original meaning, as well as its nuances?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Columbus, Claudette Kemper. Mythological Consciousness and the Future: Jose Maria Arguedas. New York: Peter Lang, 1986.

‘‘Jose Maria Arguedas (1911-1969).’’ In Contemporary Literary Criticism. Edited by Sharon R. Gunton. Vol. 18. Detroit: Gale Research, 1981.

Kokotovic, Misha. The Colonial Divide in Peruvian Narrative: Social Conflict and Transculturation. Eastborne, U.K.: Sussex Academic Press, 2005

Millay, Amy Nauss. Voices from the Puente Viva: The Effect of Orality in Twentieth-Century Spanish American Narrative. Lewisburg, Penn.: Bucknell University Press, 2005.

Sandoval, Ciro A., and Sandra M. Boschetto-Sandoval. Jose Maria Arguedas: Reconsiderations for Latin American Cultural Studies. Athens: Ohio University Center for International Studies, 1997.

Periodicals

Gold, Peter. ‘‘The indigenista Fiction of Jose Marla Arguedas.’’ Bulletin of Hispanic Studies 50 (January 1973): 56-70.