World Literature

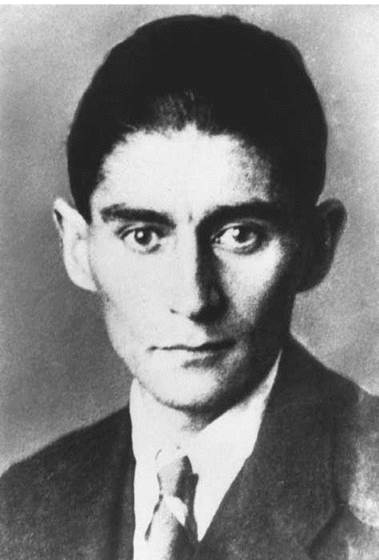

Franz Kafka

BORN: 1883, Prague, Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic)

DIED: 1924, Vienna, Austria

NATIONALITY: Czech

GENRE: Fiction, short story

MAJOR WORKS:

The Metamorphosis (1915)

The Country Doctor: A Collection of Fourteen Short Stories (1919)

The Trial (1925)

The Castle: A Novel (1926)

Amerika (1927)

Franz Kafka. Kafka, Franz, photograph. AP Images.

Overview

Czech writer Franz Kafka is one of the founders of modern literature. His most famous works, including ‘‘The Metamorphosis,’’ The Trial, and The Castle have come to be seen as stories of the struggles of individuals to preserve their dignity and humanity in an increasingly faceless and bureaucratic world. Kafka’s masterful use of the German language and his odd blend of the surreal and the mundane combine to create a unique style of fiction that has proven endlessly fascinating to readers, critics, and other writers for nearly one hundred years.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Kafka was born on July 3, 1883, in Prague, a large provincial capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that was home to many Czechs, some Germans, and a lesser number of German-cultured, German-speaking Jews. His father, Hermann Kafka, of humble rural origin, was a hardworking, hard-driving, successful merchant. His mother tongue was Czech, but he spoke German, correctly seeing the language’s importance in the struggle for social and economic mobility and security. Kafka’s mother, Julie Lowy Kafka, came from a family with older Prague roots and some degree of wealth. She would ultimately prove unable to defuse the tensions between her brusque, domineering husband and her quiet, very sensitive son.

The Father-God. Kafka’s father was a powerful, robust, imposing man, successful in his business, who considered his son a weakling unfit for life. Franz’s childhood and youth were overshadowed by constant conflict with his father, whom he respected, even admired, and at the same time feared and subconsciously hated. Kafka later transformed the total lack of communication between them into a recurring relationship in his stories between a God/Father figure and mankind.

Franz Kafka attended only German schools: from 1893 to 1901 the most authoritarian grammar school, the Deutsches Staatsgymnasium in the old Town Square, and from 1901 to 1906 the Karl Ferdinand University of Prague. In college he initially majored in German literature, but changed in his second semester to the study of law. In June 1906 he graduated with a degree of doctor of jurisprudence.

Civil Service During World War I. In October 1906 Kafka started to practice law at the criminal court and later at the civil court in Prague, meanwhile gaining practical experience as an intern in the office of an attorney. In early 1908 he joined the staff of the Workmen’s Compensation Division of the Austrian government. Apparently, he did his job admirably well—so well in fact that his supervisors arranged for him to be excused from military service during World War I. Kafka’s generation of young men was decimated by the brutal European war. Between 1914 and 1918, more than one million Austro-Hungarian soldiers were killed, and more than three and a half million were wounded.

Early Work and Engagement to Felice Bauer. Kafka’s first collection of stories was published in 1913 under the title Contemplation. These sketches are polished, light impressions based on observations of life in and around Prague. Preoccupied with problems of reality and appearance, they reveal his objective realism based on urban middle-class life. The book is dedicated to ‘‘M. B.,’’ that is, Max Brod, who had been Kafka’s closest friend since their first meeting as university students in 1902.

In September 1912 Kafka met a young Jewish girl from Berlin, Felice Bauer, with whom he fell in love—an affair that was to have far-reaching consequences for all his future work. The immediate result was an artistic breakthrough: He composed in a single sitting, on the night of September 22-23, the story ‘‘The Sentence’’ (also translated as ‘‘The Verdict’’), dedicated to his future fiancee, Felice, and published the following year in Brod’s annual, Arcadia. The story blends fantasy, realism, speculation, and psychological insight and contains all the elements normally associated with Kafka’s disorderly world. In the story, judgment is passed by a bedridden, authoritarian father on his conscientious but guilt- haunted son, who obediently commits suicide.

Kafka’s next work, completed in May 1913, was the story ‘‘The Stoker,’’ later incorporated in his fragmentary novel Amerika and awarded the Fontane Prize in 1915, his first public recognition.

Early in 1913 Kafka became unofficially engaged to Felice in Berlin, but by the end of the summer he had broken all ties, sending a long letter to her father with the explanation that his daughter could never find happiness in marriage to a man whose sole interest in life was literature. The engagement, nevertheless, was officially announced in June 1914, only to be dissolved six weeks later. The two maintained a relationship for some time thereafter.

‘‘The Metamorphosis”. The year 1913 saw the publication of Kafka’s best-known story, ‘‘The Metamorphosis,’’ about a man who is transformed into an insect. Shortly thereafter, Kafka created one of the most frightening stories in the novella In the Penal Colony, written in 1914. Though he had escaped the horrors of battle during the World War I years, the privations of life in Prague during the war weakened his health. In 1917, he learned he had tuberculosis; around the same time, he broke off his relationship with Felice. In 1919, he developed a serious case of influenza. Kafka’s illnesses did not halt his literary output. The stories Kafka wrote during the war years, were published in 1919 in a collection dedicated to his father and entitled ‘‘The Country Doctor.’’ In 1922, he published the story ‘‘The Hunger Artist.’’ ‘‘The Hunger Artist’’ became the title story for the last book published during the author’s lifetime, a collection of four stories that appeared in 1923.

Unfinished Novels. Kafka’s three great novel fragments, Amerika, The Trial, and The Castle, might have been lost to the world had it not been for the dedication of Max Brod, who edited them posthumously, ignoring his friend’s request to destroy all of his unpublished manuscripts.

The first of them, begun in 1912 and originally referred to by Kafka as The Man Who Disappeared, was published in 1927 under the title Amerika. The book, which may be considered a Bildungsroman, or novel of education (in the tradition of nineteenth-century German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship), recounts the adventures of Karl Ross- mann, who, banished by his father because he was seduced by a servant girl, emigrates to America.

Kafka’s next novel fragment, The Trial, which was begun in 1914 and published in 1925, finds the hero, Josef K., suddenly arrested and accused of a crime, the nature of which is never explained. The novel is open to multiple interpretations. Critics such as French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre have speculated that the novel was Kafka’s rendering of Jewish life in an anti-Semitic world. Indeed, though Kafka would not live to see it, anti-Semitism led to the arrest and murder of millions of Jews under the Nazi regime. All three of Kafka’s sisters died in Nazi death camps.

The third and longest of Kafka’s novel fragments is The Castle, begun in 1918 and published in 1926. The anonymous hero tries in vain to gain access to a castle that somehow symbolizes security and in which a supreme master dwells. Again and again he seeks to settle in the village where the castle is located, but his every attempt to be accepted as a recognized citizen of the community is thwarted.

Ill Health and a Love Affair. During the years 1920 to 1922, when he was working on The Castle, Kafka’s health deteriorated and he was forced to take extensive sick leave. After June 1922 there were no more renewals of Kafka’s sick leaves from the insurance company where he worked, and in July he retired on a pension. He left Prague to live with his sister Ottla in southern Bohemia for several months and then returned to Prague where he continued work on The Castle. In the summer of 1923 he vacationed on the Baltic coast with his sister Elli and her family. There he met Dora Diamant, a young girl of Hasidic roots. Her family background and her competence in Hebrew appealed to Kafka equally with her personal attractiveness. He fell deeply in love with her. She remained with him until the end, and under her influence he finally cut all ties with his family and managed to live with her in Berlin. For the first time he was happy, free at last from his father’s influence.

He lived with Dora in Berlin until the spring of 1924, when she accompanied him to Austria. There he entered Kierling sanatorium near Klosterneuburg. In 1923 and 1924, when able, Kafka worked on three stories that were published posthumously: ‘‘A Little Woman,’’ ‘‘The Burrow,’’ and ‘‘Josephine, the Songstress; or, The Mice Nation.’’ He died on June 3, 1924, of tuberculosis of the larynx.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Kafka's famous contemporaries include:

Theodore Dreiser (1871-1945): American realist writer of the naturalist school.

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973): Influential artist, codeveloper of the movement known as cubism, which helped usher in a new Modernist period in art.

Federico Garcia Lorca (1898-1936): Spanish poet and dramatist killed by the Nationalists at the start of the Spanish Civil War.

Maxim Gorky (1868-1936): Russian writer and political activist who was one of the creators of the literary school of socialist realism.

Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924): President of the United States from 1913 to 1921, chiefly remembered today for his foreign policy following the end of World War I.

H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937): American writer of horror, fantasy, and science fiction tales, he imagined an entire "mythos" filled with uncaring cosmic beings and wholly alien supernatural entities.

Nikola Tesla (1856-1943): Serbian physicist, engineer, and inventor who discovered AC (alternating current), invented the radio, and laid the groundwork for radar, robotics, and remote control.

Works in Literary Context

Even as a youngster, Kafka wanted to write. For his parents’ birthdays he would compose little plays, which were performed at home by his three younger sisters, while he himself acted as stage manager. The lonely boy was an avid reader and became deeply influenced by the works of Goethe, Pascal, Flaubert, and Kierkegaard.

Kafka-esque Qualities. The narrative features that are typical of Kafka are a first-person narrator who serves as a persona of the author, an episodic structure, an ambivalent quester on an ambiguous mission, and pervasive irony. He developed and strengthened these themes largely on his own over the course of his writing career, but they are present almost from his earliest stories. Other interpretations of his works that cast them in larger movements or philosophies are varied and still the subject of much debate.

Kafka’s works anticipate the appearance of the literary movement of magical realism during the 1940s and 1950s. Writers in this circle, such as Italo Calvino, Isabel Allende, Gunter Grass, and Jorge Luis Borges, attempted to encompass objective reality as well as psychological processes. The text itself constructs its own reality, to which the reader must adapt or else be left feeling like an outsider.

Existentialism. Perhaps Kafka’s early reading of the philosopher Kierkegaard imbued his stories and his protagonists with ideas that would later be called existentialism, a family of philosophies that interpret human existence in its concreteness and problematic character. An important tenet of existentialism is that the individual is not a detached observer of the world, which is essentially chaotic and indifferent to humans. Humans make themselves what they are by choosing a way of life. Kafka’s alienated protagonists often choose to accept the absurdity of their situation, which leads to their demise.

Influence. Kafka’s blend of surreal confusion and dark humor have influenced many artists in the decades following his death. Italian film director Federico Fellini is perhaps the most visibly ‘‘Kafka-esque’’ cinematic storyteller, rivaled only by David Lynch. Among the authors who owe a debt to Kafka’s work are Vladimir Nabokov, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Milan Kundera, Albert Camus, and Salman Rushdie.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Many other writers have explored themes of alienation and transformation and their often tragic outcomes, both before and after Kafka.

''The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' (1886), by Robert Louis Stevenson. In this, one of Stevenson's early stories, a physician uses a potion to change himself into an evil, repulsive man, an intentional transformation with results every bit as dire as those in Kafka's ''The Metamorphosis.''

Frankenstein (1818), by Mary Shelley. A classic novel about a monster who is frustrated in his attempts to connect with human beings. The monster is a rational, thinking creature that finds himself utterly rejected by those around him. His relationship with the scientist who creates him echoes the recurring Father/God theme in Kafka's writing.

''The Fly'' (1957), by George Langelaan, is a story that focuses on a scientist who transforms himself into a fly. The story was reprinted in Wolf's Complete Book of Terror, edited by Leonard Wolf (Potter, 1979), and was made into movies under the same name in 1958 and 1986.

The Stranger (1942), by Albert Camus. Also translated as The Outsider, this is a novel concerning an alienated outsider who inexplicably commits a murder.

Notes from Underground (1864), by Fyodor Dostoevsky. A novel-length monologue by an alienated antihero who stays indoors and denounces the world outside.

Works in Critical Context

The body of critical commentary on the works of Franz Kafka is massive enough to have warranted the description ‘‘fortress Kafka.’’ Here two of the author’s most well-known works will be examined by way of demonstrating the great depth and variety of interpretations that arise from Kafka’s works.

The Trial. Critics have approached The Trial from multiple directions. Some have taken a biographical approach, reading the novel through the lens of Kafka’s own diary and seeing his book as a reflection of his anxiety over his engagement to Felice Bauer. In his Anti-Semite and Jew: An Exploration of the Etiology of Hate, Jean-Paul Sartre interpreted the novel as Kafka’s reaction to being a Jew in an anti-Jewish society. Others have sought literary inspirations for The Trial: critic Guillermo Sanchez Trujillo devoted twenty years of his academic career to examining connections between Kafka’s book and the works of nineteenth-century Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. No interpretation is considered definitive, and the novel continues to spark critical interest.

“The Metamorphosis’’. Gabriel Garcia Marquez has said that it was upon reading ‘‘The Metamorphosis’’ that he realized ‘‘that it was possible to write in a different way.’’ By 1973, Stanley Corngold was able to publish a collection of essays on ‘‘The Metamorphosis’’ containing summaries of well over a hundred articles, written as early as 1916, when Robert Miller described the story as ingenious but implausible. In subsequent years, commentators have generally taken for granted the quality and importance of the story and have focused on trying to interpret it.

There have been many different and contradictory interpretations. Freudian critics have seen in it a working out of the Oedipal struggle between a father and a son who are rivals for Gregor’s mother. Marxist critics have seen the story as depicting the exploitation of the working class. Gregor Samsa has also been seen as a Christ figure who dies so that his family can live.

Critics interested in language and form have seen the story as the working out of a metaphor, an elaboration on the common comparison of a man to an insect. Some critics have emphasized the autobiographical elements in the story, pointing out the similarities between the Samsas’ household and the Kafkas’ while also noting the similarity of the names ‘‘Samsa’’ and ‘‘Kafka,’’ a similarity that Kafka himself was aware of, though he said—in a conversation cited in Nahum Glatzer’s edition of his stories—that Samsa was not merely Kafka and nothing else.

Responses to Literature

1. Father-son relationships play a major role in Kafka’s work. The interactions have reminded many of psychologist Sigmund Freud’s description of the so- called Oedipus complex. Using your library and the Internet, research the Oedipus complex. Do you think it provides a useful framework for discussing Kafka’s work?

2. Whether in literary forms, science fiction, movies, or television shows, Kafka has proved to be a major source of inspiration. Select a work that you feel is Kafka-esque and write an essay in which you defend your choice by comparing it to one of Kafka’s stories.

3. What would you do if you awoke one morning to find, like Gregor Samsa, that you had the body of a giant insect? Describe how you would feel, how you think your family and friends would react, and how you might try to adjust to your new form and appearance.

4. Kafka’s novel The Trial has often been interpreted as a religious commentary. How much do you think such a critique is supported by the text? Pick a religion, such as Calvinism, Catholicism, or Judaism, and discuss the possible textual evidence for its influence.

5. One interpretation of Kafka’s story ‘‘A Hunger Artist’’ suggests that this depiction of an artist who creates his work through periods of voluntary starvation is an allegory of the role of the artist in the modern world. Write an essay in which you analyze the story and support this interpretation. Apply the interpretation to writers and artists with whom you are familiar.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Hamalian, Leo, comp. Franz Kafka: A Collection of Criticism. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1974.

Hayman, Ronald. Kafka: A Biography. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Heller, Erich. The Basic Kafka. New York: Pocket Books, 1979.

Janouch, Gustav. Conversations with Kafka. New York: New Directions, 1969.

Politzer, Heinz. Franz Kafka: Parable and Paradox. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1966.

Robert, Marthe. As Lonely as Franz Kafka. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982.

Periodicals

McCort, Denis. ‘‘Kafka and the East: The Case for Spiritual Affinity.’’ Symposium(Winter 2002): vol. 55.4: 199.

Powell, Matthew T. ‘‘From an urn already crumbled to dust: Kafka’s Use of Parable and the Midrashic Mashal’’. Renascence: Essays on Values in Literature (2006): vol. 58.4: 269.

Web sites

Nervi, Mauro.The Kafka Project. Accessed February 15, 2008, from http://www.kafka.org