World Literature

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis

BORN: 1839, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

DIED: 1908, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

NATIONALITY: Brazilian

GENRE: Fiction, poetry, plays, essays

MAJOR WORKS:

Epitaph of a Small Winner (1881)

Quincas Borba (1891)

Dom Casmurro (1899)

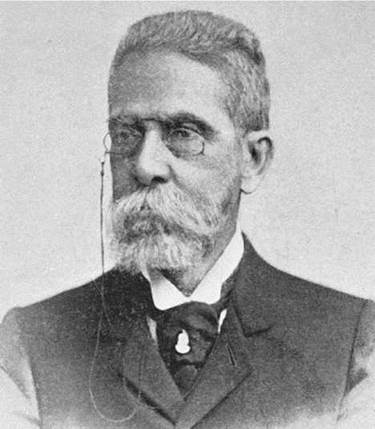

Joaquim Machado de Assis. Machado de Assis, Joaquim, photograph. The Library of Congress.

Overview

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis is thought by many to be Brazil’s greatest writer. Although he wrote in many genres, he achieved his greatest literary successes in the novel and short-story forms. A complex blend of psychological realism and symbolism, Machado’s fiction is marked by pessimism, sardonic wit, an innovative use of irony, and an ambiguous narrative technique.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Early Success and a Change in Perspective. Machado was born in Rio de Janeiro on June 21, 1839, to a Portuguese mother who died when he was ten; his father was a house painter. Machado had epilepsy and a speech impediment, which are thought to have made him very self-conscious. Machado did not receive a formal education, and most of his learning occurred while working as a printer’s apprentice. During these years, Machado began writing poems and stories. When Machado began working as a proofreader at a bookstore, he met many prominent literary figures. These contacts helped Machado get his first works published, which launched his career as a writer. He was an early success, and his work was widely acclaimed by the time he was twenty-five.

In 1860 he entered the civil service, to which he dedicated himself, and he eventually attained the directorship of the Ministry of Agriculture. Over the next decade, while working for the ministry, Machado wrote mostly poetry and several comedies—drama being his first literary passion—before he gave more serious attention to narrative fiction.

In 1879 Machado suffered a serious illness, and the long convalescence allowed him time to change his worldview. When he returned to writing, he began a novel radically different from anything he had done before. His previous works of sentimental Romanticism gave way to mordant irony. His first novel in this new period was Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas (1881), translated under the title of Epitaph of a Small Winner in 1952. The book’s narrator is deceased and is writing his memoirs as a man who has already arrived on the other side. Ten years later, Machado wrote Quincas Borba (translated under the title of Philosopher or Dog?), and his next novel, Dom Casmurro, was written in 1900.

The Brazilian Academy of Letters. The formation of the Brazilian Academy of Letters began after the proclamation of the republic in 1889. The best writers in Brazil, including Machado, were brought together to contribute to Revista Brasileira (Brazilian Review). Within this group, there was a movement to establish an academy along the lines of the famous Academie franyaise. When the academy was officially constituted in 1897, Machado was named the first president in perpetuity, a title he held until his death on September 29, 1908.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Machado's famous contemporaries include:

Jose de Alencar (1829-1877): Brazilian novelist whose works advocated a fiercely independent nationalism.

Giosue Carducci (1835-1907): Italian poet widely considered one of Italy's greatest writers.

Rosalia de Castro (1837-1885): Galician poet who is considered to be one of Spain's best poets.

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928): English writer whose poetry was part of the naturalist movement.

Claude Monet (1840-1926): French artist who was one of the founders of impressionism.

Stephane Mallarme (1842-1898): French poet and critic who influenced the development of Dadaism.

Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900): English composer best known for his collaborations with William Gilbert on comic light operas.

Works in Literary Context

Among Latin American fiction writers of the nineteenth century, Machado is without peer. He emerged from undistinguished biographical and literary origins with a brilliant and subtle voice that set him apart from his contemporaries and pointed the way to the Ibero-American literary boom of the twentieth century. Though Machado’s first novels and poetry were characteristically Romantic, the maturing writer became more contemporary. Machado could see that Romanticism was past its prime, but he had problems with the values of realism and naturalism so prevalent among the Brazilian writers of his day. Instead, he sought narrative models from the eighteenth century, especially those involving a meandering, free-associative style.

According to the Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes, Machado’s adherence to the early traditions of the novel made him the legitimate heir of Miguel de Cervantes. Paradoxically, Machado’s devotion to past models made him an important precursor of future trends. Through self-reference, irony, the rejection of strict verisimilitude, and an emphasis on the relativity of events and actions, the Brazilian author, more than any other Latin American of his century, cleared ground for Jorge Luis Borges and his successors.

Short Fiction with a Broad Range. Having a much broader range than his novels, Machado’s short fiction is concerned with the destructiveness of time, the nature of madness, the isolation of the individual, conflicts between self-love and love for others, and human inadequacy. Often humorous, Machado’s stories portray the thoughts and feelings, rather than the actions, of characters who often exemplify Brazilian social types. Machado’s stories deal satirically with cultural institutions and contemporary social conditions. His short fiction favors selfrevealing dialogue and monologue rather than description or narration.

Unlike his novels, very few of Machado’s more than two hundred short stories have been translated into English, but those that have represent his most accomplished works in the genre. These include ‘‘The Psychiatrist,’’ which struggles with the twin questions of who is insane and how one can tell; “Alexandrian Tale,’’ a satirical attack on the tendency to use science to cure human problems; ‘‘The Companion,’’ one of Machado’s most anthologized tales, in which a man hired to care for a cantankerous old invalid is driven to murder him instead; and ‘‘Midnight Mass,’’ regarded by most as his best single story, which relates the events surrounding an ambiguous love affair between the young narrator and a married woman.

Works in Critical Context

Some critics have interpreted Machado’s narrative art as being part of the realistic trend in literature, but most have identified his work with the modern movement, linking the style and technique of his fiction to writers such as Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and Thomas Mann. Other scholars have examined Machado’s works as an influence in the construction of a postcolonial Brazilian national identity and for indications of the author’s stand on racism and civil rights. As international readers have slowly discovered his fiction through translation, most agree that Machado’s narrative art is the work of a largely unrecognized genius.

Outside his native Brazil, Machado’s short stories are relatively unknown and consequently have received little international critical attention. This lack of recognition is attributed in part to the fact that Portuguese is not widely accepted as a literary language, and Brazilian literature, in particular, makes up a small part of the traditional Western canon. According to Earl Fitz, ‘‘[H]ad [Machado] written in French, German, or English, for example, [he] would be as well-known today as Flaubert, Goethe, or Shakespeare.’’

Epitaph of a Small Winner. Machado’s best-known novel, Epitaph of a Small Winner, is often cited as the first modern novel of the Western Hemisphere. It appeared in installments in 1880 and was published as a book the following year. With the early installments it became clear that Machado was finished with his previous models of sentimental Romanticism; irony, wit, and pessimism had become his new mediums. The unobtrusive third-person narrators of the past were replaced by a brash and impudent first-person narrator, interacting aggressively with the reader.

Machado’s readers, including his close friends, apparently had a hard time knowing what to make of Epitaph of a Small Winner. Capistrano de Abreu went so far as to ask if it was a novel at all. Noteworthy is Machado’s response to that question, which appears in the preface to the third edition of the novel. Rather than directly answering the question, Machado quotes his narrator, saying that it would seem to be a novel to some but not to others. Responding to remarks about the book’s pessimism, Machado again quotes his narrator, who characterizes his own account as pessimistic. Machado ends by saying, ‘‘I will not say more, so as not to become involved in the analysis of a dead man, who painted himself and others in the way that to him seemed most fitting.’’ Machado seems to have tried to draw an important line here. He wanted his readers not to look to him, the author, for the ‘‘real meaning’’ of the book. The book has a narrator, and the opinions expressed in the book are his. As that narrator himself says on the opening page, ‘‘The work in itself is everything.’’

Dom Casmurro. Many critics feels that Dom Casmurro is the finest novel ever written in both Americas. The history of the reception of Dom Casmurro has involved diametrically opposed ways of reading the novel. The narrative is told by a digressive and eccentric first- person narrator, Bento Santiago, who has grown old and now finds himself alone and uneasy. He vows to recover the happier moments of his youth by writing a memoir. The narrator thus recounts the adolescent romance he experienced with Capitu, the girl next door. The sweet love story turns into bitterness, however, when after several years of marriage and the birth of a son, Bento becomes convinced that Capitu has been unfaithful to him with his friend from the seminary.

Published reviews and analyses show that for generations readers accepted the narrator’s perspective at face value, assuming that Capitu was guilty of adultery. The tide of opinion began to change in 1960, with Helen Caldwell’s The Brazilian Othello of Machado de Assis, in which she claims that Capitu is the innocent victim of her husband’s jealous and domineering mind. That view gained favor, particularly since Roberto Schwarz’s ‘‘discovery’’ of Caldwell in Duas meninas (1997), and it seems to have become the prevailing opinion in Brazil. Both the reading of Capitu as adulteress and the reading of her as innocent victim, however, are partial and unbalanced. The more critically acute reading is that Machado wrote an ambiguous novel in which the truth of Santiago’s claims against his wife cannot possibly be determined with any degree of confidence.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Machado's novels reject the attempt at an objective, truthful narrative in favor of exploring the relativity of events and actions. Here are some other works that take a similar approach:

Don Quixote (1605, 1615), a novel by Miguel de Cervantes. This two-volume novel, often seen as a satire of orthodoxy, truth, and veracity, follows the largely imagined adventures of a farcical knight.

''The Tell-Tale Heart'' (1843), a short story by Edgar Allan Poe. This short horror story recounts the murder of an elderly man, but the reader is unsure whether the account is true or the ranting of a madman.

The Two Deaths of Quincas Wateryeii (1959), a novel by Jorge Amado. This novel shows how two different groups of people compete over the memory of a single, unusual man who has recently died.

Seven Types of Ambiguity (2003), a novel by Elliot Perlman. This novel tells the story of a peculiar crime from the perspective of seven different characters who were directly or indirectly involved.

Responses to Literature

1. Critics disagree about whether Machado’s works should be considered realist or modernist. Which designation seems more appropriate? Does Machado defy categorization? Why or why not?

2. Read one of Machado’s short stories and discuss the reliability of the narrator. Discuss how the narrator’s reliability affects the reader’s interpretation of the plot.

3. Machado is noted for creating uncertainty and ambiguity in his novels and short stories. Write a story that re-creates this kind of ambiguity.

4. Machado avoided commenting on the ‘‘real meaning’’ of his books. He asserted instead that ‘‘the work in itself is everything.’’ Write an essay supporting this assertion.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Baptista, Abel Barros. Em nome do apelo do nome: duas interrogagoes sobre Machado de Assis. Lisbon: Litoral, 1991.

Caldwell, Helen. The Brazilian Othello of Machado de Assis: A Study of Dom Casmurro. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960.

Carvalho Filho, Aloysio de. Oprocesso penal de Capitu. San Salvador: Regina, 1958.

Dixon, Paul B. Reversible Readings: Ambiguity in Four Modern Latin American Novels. University, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1985.

Fitz, Earl E. Machado de Assis. Boston: Twayne, 1989.