World Literature

Vladimir Nabokov

BORN: 1899, Saint Petersburg, Russia

DIED: 1977, Montreaux, Switzerland

NATIONALITY: Russian-American

GENRE: Fiction, poetry

MAJOR WORKS:

King, Queen, Knave (1928)

Speak, Memory (1951)

Lolita (1955)

Pale Fire (1962)

Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle (1969)

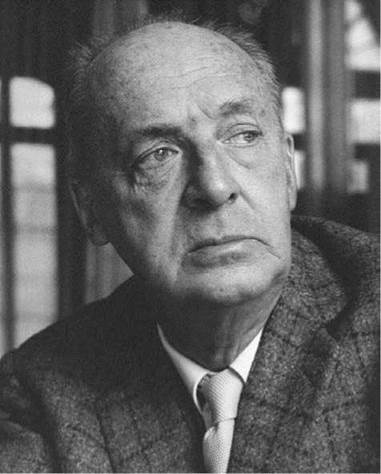

Vladimir Nabokov. Nabokov, Vladimir, photograph. Gertrude Fehr / Pix Inc. / Time and Life Pictures / Getty Images.

Overview

Novelist, literary critic, chess enthusiast, and butterfly expert, Vladimir Nabokov left behind a body of work characterized by a love of language and wordplay. Although his style markedly changed over time, becoming increasingly less lyrical, all his works are marked by a complex and sophisticated attention to detail. He achieved worldwide fame in 1955 with his highly controversial Lolita, the story of a middle-aged man’s love affair with a twelve-year-old ‘‘nymphet.’’

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Family with Liberal Leanings. Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, on April 22, 1899, to Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, a distinguished jurist known for his liberal political views, and Elena Ivanovna Rukavishnikova. Nabokov’s father was an Anglophile, and the family had a leaning toward English products that included not only English soap and syrup but also a series of English governesses. As a result, Nabokov initially learned to speak English better than Russian.

A Numb Fury of Verse-Making. Nabokov’s parents encouraged him to follow his mind and imagination. He played with language and linguistics, mathematics, puzzles and games, including chess, and sports from soccer to boxing to tennis. Interested in butterflies, he became a recognized entomological authority while still young and remained a noted butterfly expert his entire life. Nabokov began to write poems when he was thirteen and, as he described it, ‘‘the numb fury of verse-making first came over me.’’ He began writing poems in Russian, French, and English, but his real passion for writing poetry began in 1914.

Fleeing Revolutionary Russia. Nabokov’s father, a lawyer who edited St. Petersburg’s only liberal newspaper, rebelled against first the czarist regime, then against the communists. He was an active member of the Duma (the Russian parliament) until he was briefly jailed and stripped of his political rights in 1908 for signing a manifesto opposing conscription. In February of 1917, at the height of world war i and in the midst of a chaotic military mutiny, the Duma seized power, thus creating the Russian provisional government. Later that same year, Vladimir Lenin led the Bolsheviks in overthrowing this new governing body, thus inciting a bloody civil war. The Russian Revolution, as these two events are called, marked the transfer of governing power from the czarist autocracy to the Soviet Union, ending the Russian Empire. After the Russian Revolution, deprived of their land and fortune, the family fled Russia for London in 1919, where Nabokov and his brother entered Cambridge University. At Cambridge, Nabokov graduated with honors in 1922 and rejoined his family in Berlin in the wake of an unexpected tragedy. Nabokov’s father was assassinated in Berlin by Russian monarchists as he tried to shelter their real target, Pavel Milyukov, a leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party-in-exile.

Romance and Marriage After relocating to Berlin permanently, Nabokov received some income from public readings and from his publications, which included not only literary works but also journalistic pieces and chess problems, but he found a more reliable means of support in providing instruction in French and English to students, primarily Russians. A romance with Svetlana Sie- wert, the subject of several of his poems, was terminated in January 1923 by her parents, who had insisted that he obtain a steady job as a condition for becoming engaged to their daughter. A few months later, he met his future wife, Vera Slonim, at a charity ball. Sensitive and intelligent, she could recite Nabokov’s poetry by heart and became indispensable to him.

Nabokov married Slonim in 1925. In the fall, Nabokov wrote his first novel, Mary (1926). Based on Nabokov’s relationship with Valentina Shulgina (Nabokov’s first love), Mary is perhaps the most poetic novel Nabokov ever wrote. The original Russian version of the book received little attention, but after Nabokov’s reputation burgeoned and the work was translated into English, Mary received closer critical attention.

Growing Literary Reputation and Travel. As his literary reputation grew, Nabokov traveled extensively throughout Europe, visiting his siblings and giving readings of his work. In 1937, he obtained permission for his family to relocate to France. It was at this time that Nabokov began to experiment with English, translating his Russian novel Otchayanie (1934) into the English Despair in 1937. After Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany, the Nabokovs fled the Nazi advance into France in 1940 and sailed to the United States.

Early Days in America: A Series of Professorships. His next book, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1941), was written in English and marks the demise of the use of the pen name V. Sirin and the emergence of Vladimir Nabokov, an American writer. In 1940, Nabokov taught Slavic languages at Stanford University. From 1941 to 1948, he taught at Wellesley College and became a professor of literature. He was also a research fellow in entomology at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University from 1942 to 1948 and later discovered several butterfly species and subspecies, including ‘‘Nabokov’s wood nymph.’’ A Guggenheim fellowship in 1943 resulted in his scholarly 1944 biographical study of Russian author Nikolai Gogol. Nabokov became an American citizen in 1945 and by then was a regular contributor to popular magazines.

In 1949 Nabokov was appointed professor of Russian and European literature at Cornell University, where he taught until 1959. In 1951 he published the memoir of his early life in Russia, Speak, Memory. Six years later, several short sketches published in the New Yorker were incorporated into Pnin (1957), his novel about a Russian emigre teaching at an American university.

Lolita Brings Notoriety. Despite Nabokov’s vast productivity, scholarly status, and high standing in literary circles, Nabokov did not gain widespread popularity until the publication of Lolita. The story of a middle-aged man’s obsessive and disastrous lust for a twelve-year-old schoolgirl, Lolita is widely considered one of the most controversial novels of the twentieth century. Rejected by four American publishers because of its pedophiliac subject matter, the book was finally published by Olympia Press, a Parisian firm that specialized in pornography and erotica. Lolita attracted a wide underground readership, and tourists began transporting copies of the work abroad. While U.S. Customs permitted this action, the British government pressured the French legislature to confiscate the remaining copies of the book and forbid further sales. However, the English author Graham Greene located a copy and, in a pivotal London Times article, focused on the novel’s language rather than its content, designating Lolita one of the ten best books of 1955. Public curiosity and controversy fueled the book’s popularity, and in 1958 it was published in the United States. Within five weeks, Lolita was the most celebrated novel in the nation and remained on the New York Times best-seller list for over a year.

Nabokov sold the film rights and wrote the screenplay for the 1962 movie directed by Stanley Kubrick. With royalties from the novel and the film, Nabokov was able to quit teaching and devote himself entirely to his writing and to butterfly hunting.

In 1959 Nabokov published Invitation to a Beheading, a story of a man awaiting execution, which he had first written in Russian in 1938. In 1960 he and his family moved to Montreaux, Switzerland. Nabokov received critical acclaim for Pale Fire (1962), a strange, multidimensional exercise in the techniques of parable and parody, written as a 999-line poem with a lengthy commentary by a demented New England scholar who is actually an exiled mythical king.

In his seventieth year, Nabokov produced his last major work, Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle (1969), a sexually explicit tale of incest, twice as long as any other novel he had written and, according to the New York Times's John Leonard, ‘‘fourteen times as complicated.’’ An immediate best seller, Ada evoked a wide array of critical response, ranging from strong objections to the highest praise. While the value of the novel was debated, Ada was universally acknowledged as a work of enormous ambition that represented the culmination of all that Nabokov had attempted to accomplish in his writing over the years.

Nabokov died on July 2, 1977, at the Palace Hotel in Montreux, Switzerland, where he had lived since 1959.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Nabokov's famous contemporaries include:

Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999): Few American directors were as simultaneously revolutionary and popular as Kubrick. His films—most based on novels—are meticulously constructed masterpieces that push the boundaries of cinematic vision.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008): Russian novelist and dramatist best known for his expose of the Soviet system of political prison camps, or gulags. Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970, Solzhenitsyn was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1974.

Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930): Russian futurist poet, he coauthored the 1912 declaration A Slap in the Face to Public Taste. As a futurist, his work focused on the dynamic, hectic pace of modern life and tearing down old social orders and authority figures.

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986): American visual artist most closely associated with the American Southwest. O'Keeffe is best known for her paintings of flowers, rocks, shells, animal bones, and landscapes that synthesize abstraction and representation.

Jack Kerouac (1922-1969): A leading voice among the so-called Beat Generation, a loose association of poets, writers, and musicians that revolted against the conformity of post-World War II America, Kerouac is best known for his stream-of-consciousness travelogue, On the Road.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Nabokov often employed emotionally detached, unreliable narrators in his stories, most notably in Lolita. Other writers stretching back to the nineteenth century have approached their stories in a similar fashion; strongly rooted in Russian literature, the technique later became widespread in both fiction and film during the twentieth century. Here are some other works that share Nabokov's detachment:

The Stranger (1942), a novel by Albert Camus. One of the best known works of absurdist fiction, The Stranger features an emotionally detached, unreflecting, and unapologetic main character named Meursault.

Notes from Underground (1864), a novel by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Narrated by a bitter, anonymous bureaucrat, this short novel is a collection of disjointed and often contradictory notes that decry the central character's alienation from his fellow man.

Diary of a Madman (1835), a short story by Nikolai Gogol. Considered one of his greatest works, and written from the first-person perspective of a diarist slowly slipping into love-induced insanity, Gogol plays with perceptions of reality and trustworthiness.

Psycho (1960), a film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. This groundbreaking work utilizes two unreliable narrators, first introducing a female ''lead'' who is quickly killed off, then misleading the audience as to the relationship between Norman Bates and his mother.

Works in Literary Context

Nabokov stated that his fiction expresses his passionate regard for human feelings and morality. Yet, some critics have accused Nabokov of being indifferent to social and political issues of his time, comparing his stories and novels to elegantly constructed, labyrinth-like narratives and riddles. This similarity is largely because of Nabokov's curious ability to combine his passion for literature with his strong interest in chess and crosswords. Many of Nabokov's stories share the motifs, themes, and techniques of his larger narratives and function as ‘‘little tragedies,'' with some mythological, psychological, and metaphysical overtones. While he has been compared to author Joseph Conrad by some critics, Nabokov was critical of other prominent authors and rejected such comparisons. It was the authors he read in his youth, like Aleksandr Blok, that exerted the most influence on his poetic works.

Themes in Lolita. It has been suggested that the character Dolores, whom Nabokov's antihero Humbert Humbert idealizes as ‘‘Lolita,'' represents the superficiality of American culture viewed from a sophisticated European perspective. While other literary scholars do not deny this interpretation, they view an examination of the effects of the artist's antisocial impulses in addition to Lolita's satirical vision of American morals and values. Several commentators maintained that the accusations of pornography stemmed from Nabokov's lack of moral commentary regarding Humbert's actions, while some argued that the true crime of the novel is not the murder Humbert commits but his cutting short of Lolita’s childhood. Critics feel that Lolita is not entirely blameless, however, for at twelve she is already sexually active, and, despite Humbert's extravagant designs, it is she who first seduces him. Lolita’s character, as well as other characterizations in the novel, have won Nabokov consistent, unified praise for his ability to evoke both revulsion and sympathy in the reader. For example, it is generally agreed that Lolita has a truly unattractive personality, yet her unhappy life inspires compassion. Humbert is a pedophile and murderer but wins the reader's appreciation for his humor and brutal honesty, while Charlotte, Dolores's mother, is depicted as both a piranha and a pawn.

Throughout Lolita, Nabokov challenges the reader. The novel’s foreword, written by ‘‘John Ray, Jr., PhD,’’ a bogus Freudian psychiatrist, introduces Humbert's confession through overly complex psychological jargon, which Nabokov hated. Unwitting readers believe the foreword is sincere, especially because of Lolita's controversial subject matter. Nabokov's myriad uses of anagrams, coded poetry, and puns provide clues concerning Lolita's mysterious lover. Nabokov also parodies numerous styles of literature in Lolita; it is at times viewed as a satire of the confessional novel, the detective novel, the romance novel, and, most frequently, as an allegory of the artistic process.

Influencing a Generation of Postmodernists. Nabokov’s powerful writing impacted his contemporaries, such as John Banville, Don DeLillo, Salman Rushdie, and Edmund White, as well as generations of authors after him. Other prominent authors that acknowledge Nabokov’s influence include Martin Amis, John Updike, Thomas Pynchon, Pulitzer Prize winner Michael Chabon, Pulitzer Prize winner Jeffrey Eugenides, T. Coraghessan Boyle, Jhumpa Lahiri, Marisha Pessl, and Zadie Smith.

Works in Critical Context

Nabokov earned a secure reputation as one of the twentieth century’s most inventive writers. His prose was lauded as both complex and playful, and his descriptive power was unparalleled. While many of his novels might be regarded as masterpieces, it is the blockbuster Lolita for which he is most remembered.

Lolita. The initial reviews of Lolita were varied. While several critics expressed shock and distaste, most believed the ‘‘pornography’’ charges were erroneous. Praising Nabokov’s lively style, dry wit, and deft characterizations, many reviewers concurred with novelist and literary critic Granville Hicks, who called the novel ‘‘a brilliant tour de force.’ Beat novelist Jack Kerouac described Lolita as ‘‘a classic old love story,'' and Charles Rolo commented in his September 1958 Atlantic Monthly article, ‘‘Lolita seems to me an assertion of the power of the comic spirit to wrest delight and truth from the most outlandish materials. It is one of the funniest serious novels I have ever read; and the vision of its abominable hero, who never deludes or excuses himself, brings into grotesque relief the cant, the vulgarity, and the hypocritical conventions that pervade the human comedy.''

Responses to Literature

1. Research the history of the Russian emigrant community in Berlin in the 1920s through the 1940s. What part did Nabokov play in the larger community? Why did he leave Germany after the Nazis came to power, and what happened to those who chose not to leave?

2. At one point in Lolita, Humbert admits that he never found out the laws governing his relationship with Lolita. Investigate what rights Humbert had as a stepfather in 1955 and what the penalties for incest were. Investigate the effects of incest on children and compare your findings to the effects Lolita’s relationship with Humbert had on her.

3. Analyze Nabokov’s use of names in Lolita, such as how names are used in the book’s word games. How does the comical name of Humbert Humbert influence the reader's opinion of his criminal acts? How are names used to reinforce the recurring theme of coincidence?

4. Compare Nabokov’s treatment of taboo-shattering sexual relationships in Lolita and Ada or Ardor. Is there an implied moral judgment in either work? How are the relationships treated differently? How are they similar?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Alexandrov, Vladimir E. The Garland Companion to Vladimir Nabokov. New York: Garland, 1995.

Appel, Alfred, Jr., ed. The Annotated Lolita. New York: McGraw, 1970.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 317: Twentieth-Century Russian Emigre Writers. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Ed. Maria Rubins, University of London. Detroit: Gale, 2005.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 278: American Novelists Since World War II, Seventh Series. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Eds. James R. Giles, Northern Illinois University, and Wanda H. Giles, Northern Illinois University. Detroit: Gale Group, 2003.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 244: American Short-Story Writers Since World War II, Fourth Series. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Eds. Patrick Meanor, State University of New York College at Oneonta, and Joseph McNicholas, State University of New York College at Oneonta. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001.

Grayson, Jane. Nabokov Translated: A Comparison of Nabokov’s Russian and English Prose. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Mason, Bobbie Ann. Nabokov’s Garden: A Guide to Ada. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis Press, 1974.

Novels for Students. Vol. 9. Ed. Deborah A. Stanley and Ira Mark Milne. Detroit: Gale, 2000.

Short Stories for Students. Vol. 15. Ed. Carol Ullmann. Detroit: Gale, 2002.

Wood, Michael. The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Zimmer, Dieter E. A Guide to Nabokov’s Butterflies and Moths. Hamburg: D. E. Zimmer, 1996.