World Literature

R. K. Narayan

BORN: 1906, Madras, India

DIED: 2001, Madras, India

NATIONALITY: Indian

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

Malgudi Days and Other Stories (1941)

The Financial Expert (1952)

The Guide (1958)

The Man-Eater of Malgudi (1961)

Under the Banyan Tree and Other Stories (1985)

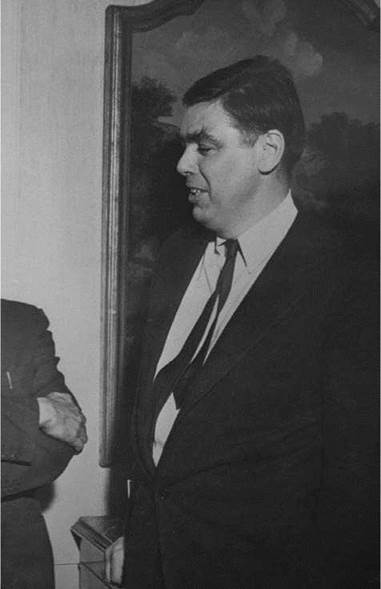

R. K. Narayan. Narayan, R. K., photograph. The Library of Congress.

Overview

When R. K. Narayan died at the age of ninety-four, he left behind a body of work that will continue to impress generations of readers. He published novels, short stories, travel books, essays, and retellings of Indian epics, as well as articles he produced as a journalist in his early years. From the 1930s to the early 1990s, he managed to write at least three books every decade. Most of Narayan’s prose centers around the fictional village of Malgudi, which Narayan used as a microcosm for studying the interaction between various classes and races of Indian society.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Early Hardships in Colonial India. Rasipuram Krishnaswami Narayan was born on October 10, 1906, in his grandfather’s home in Madras, the son of schoolteacher R. V. Krishnaswami Iyer and Gnana Iyer. Narayan spent the early years of his life in Madras in the care of his grandmother and a maternal uncle, joining his parents mainly during vacations. At the time, India was still the ‘‘jewel in the crown’’ of the British empire, a colony held since 1857. In the early years of the twentieth century, however, Indian nationalism intensified to the point that by 1919 the Government of India Act was passed giving India limited self government.

Narayan first went to school in Madras. In 1922 he was shifted to the school in Mysore where his father was the headmaster. My Days indicates that Narayan was an indifferent student but an avid reader. He failed the school entrance examination twice and also was unable to get through college easily. Eventually he did graduate from Maharaja College of Mysore with a bachelor of arts degree in 1930.

Serious Aspirations. Narayan began to write seriously in the 1920s. His biographers Susan Ram and N. Ram describe his intense desire to see his name in print and the hard work he did to accomplish this, not only reading major English writers and periodicals but also going through books on how to sell one’s manuscripts. He grew accustomed to receiving rejection slips from publishers and editors, but he continued to harbor hopes of making a living as a writer, until his father persuaded him to take up a teaching position in a school. The experience proved distasteful, and he soon returned to submitting his manuscripts. He eventually succeeded in getting an article on Indian cinema published in the Madras Mail in July 1930. The 1920s in India were also marked by the nonviolent protest campaigns of Mohandas Gandhi, whose actions were aimed at forcing Britain to relinquish control of India.

First Love, First Publication. In his memoir, Narayan recalls wandering the streets of Mysore one day when Malgudi, the setting of most of his fiction, just seemed to ‘‘hurl’’ into his mind, along with a vision of a character called Swaminathan. He thus began his first Malgudi novel, Swami and Friends, completing it two years later in 1932.

In publishing short pieces in the Indian Review and Punch, Narayan satisfied his dream of writing and seeing his name in print. Also during this time, he fell in love. He had spotted fifteen-year-old Rajam Iyer as she was waiting for water at a local street tap. He persuaded his father to send a proposal of marriage to her father. He married Rajam on July 1, 1934. Around this time, he also became the Mysore reporter of a newspaper called the Justice.

Malgudi Is Put on the Map. Narayan knew that for an Indian writing English fiction, Swami and Friends would not find a publisher in his country, and publishers in England were not responding. Sometime in 1934 he contacted his friend Krishna Raghavendra Putra, who soon persuaded the famous English novelist Graham Greene, who was already attempting to get some of Narayan’s short stories published in English magazines, to look at Swami and Friends. Greene was so impressed that he recommended the book. It appeared in October 1935, and Malgudi was launched. Though sales were weak, public and critical response was positive. The year 1935 also saw the passage of another Government of India Act that moved the country one step closer to true independence.

Stalled Writing Efforts. After The Bachelor of Arts (1937) and The Dark Room (1938), both of which sold poorly but received better and better reviews, Narayan entered the darkest period of his life: Five years into his marriage, his wife died after a short illness of what was probably typhoid. Overwhelmed with grief, he stopped writing. He finally managed to get out of his depression at the same time as the outbreak of World War II. During this time, however, Greene became inaccessible due to his involvement in the war effort, and Narayan found paths to publishing doubly difficult.

Malgudi Lives On. Narayan managed to sustain himself in this difficult period through his journalism and by giving talks on Madras radio. He became the editor of a journal called Indian Thought in 1941, and by 1944 he had managed to complete his fourth novel, The English Teacher (1945). It was widely praised and sold well in England. In 1947, Britain ceded control of India by signing the Indian Independence Act, which simultaneously created the Muslim-majority nation of Pakistan.

The author’s work returned to Malgudi in Mr. Sam- path (1949), and the fictional but no less realistic land continued in The Financial Expert (1952), arguably one of Narayan’s best and most popular novels. Narayan followed that work with his most political novel, Waiting for the Mahatma (1955), and repeated the success with The Guide (1958). Narayan followed The Guide with another triumph: The Man-Eater of Malgudi (1961). After two less popular works, Narayan’s twelfth novel, A Tiger for Malgudi (1983), made yet another impression—with a tiger as the protagonist. A Tiger for Malgudi was the last of Narayan’s novels to receive wide critical attention, but it got mixed reviews, and a few critics noted their disappointment with it.

Final Work Efforts. At eighty years old, Narayan published Talkative Man in 1986, and followed it with his last novel, The World of Nagaraj (1990), four years after. He received a number of major awards, including the Sahitya Akademi Award for The Guide, the Padma Bhushan, and several honorary degrees up until 2001, the year he died.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Narayan's famous contemporaries include:

Rachel Carson (1907-1964): Marine biologist, environmentalist, and naturalist and science writer, her work Silent Spring (1962) was instrumental in the advent of global environmentalism.

Hiroshi Inagaki (1905-1980): Japanese filmmaker who is best known for his Samurai trilogy.

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954): Mexican painter who became an influential figure with her distinctive style and representation of indigenous culture.

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980): French philosopher, writer, and critic who is often attributed with pioneering modern existentialism.

Works in Literary Context

Influences. In My Days: A Memoir (1974), the novelist says that his grandmother was a major influence on his life and his storytelling. His maternal uncle, who published a literary journal in Tamil, also played a part in the growth of the novelist’s mind in his early years. Narayan is most noted for his creation of Malgudi, a fictitious village set in southern India that most critics consider a composite of his birthplace of Madras and his adult residence of Mysore. These narratives derive from India’s oral and literary traditions.

Economical Style. Among Narayan’s strengths as a novelist are the economy of his storytelling and the skill with which he manipulates his plot so that events that complicate the lives of his central characters are resolved within a few hundred pages. Narayan is also a master of shorter forms of fiction—his five collections of short stories, such as Malgudi Days (1943), cover the same territory as the novels. The stories of the early collections are slight pieces and usually journalistic in style. Some are anecdotal or no more than character sketches. The stories of the later collections are longer and more intricately built. A few of the stories are satirical in tone and sometimes slip into the absurd.

Sympathetic Humor in Themes of Struggle. Narayan’s stories usually show people as fallible, eccentric, and often amusing. Narayan often uses wry, sympathetic humor to examine the universalized conflicts of Malgudi, focusing on ordinary characters who seek self-awareness through their struggles with ethical dilemmas. All of Narayan’s characters, in accordance with principles of Hinduism, retain a calm, dignified acceptance of fate. In his early fiction, Narayan makes use of personal experience to address conflicts between Indian and Western culture. Swami and Friends: A Novel of Malgudi (1935), for instance, chronicles an extroverted schoolboy’s rebellion against his missionary upbringing. Such novels, like Narayan’s later works, were noted for his natural and unaffected language, his subtle humor, and his ability to transform a particular lifestyle into a universal human experience.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Here are a few works by writers who focused on the tragedy of human fallibility:

The Infernal Machine (1936), a play by Jean Cocteau. In this play, the playwright turns the classic story of Oedipus into a tragic-comedy by using irony where there originally was none.

''A Rose for Emily'' (1930), a short story by William Faulkner. In this short story, Emily Grierson is alienated from her immediate society and is isolated in her aging, eccentric, and ''spinster'' years.

Snow (2005), a novel by Orhan Pamuk. In this work, a clash of ideals is witnessed by a poet in exile as he comes to terms with his alienation from poetry and God.

A View from the Bridge (1955), a play by Arthur Miller. Italian American longshoreman Eddie Carbone suffers the profound betrayals and conflicts of family and friends in this play.

Works in Critical Context

Peers as well as successors have been quick to acknowledge Narayan’s contribution to Indian writing in English. In an essay written at Narayan’s death, for instance, the distinguished Indian poet Dom Moraes called Narayan ‘‘by far the best writer of English fiction that his country has ever produced.’’ Typical of the praise heaped on the novels and their writer are comments such as those made about The Financial Expert and The Guide.

The Financial Expert (1952). The Financial Expert shows Narayan’s powerful handling of the central theme of the vanity of human wishes and his deft manipulation of plot. The portrait of the central character, Margayya, reveals a man who is deeply flawed but also capable of retaining the reader’s sympathy. The novel is memorable, too, for the portraits of Dr. Pal, the archetypal confidence man; Meenakshi, Margayya’s long-suffering wife; and Balu, his prodigal son.

Margayya’s rise and fall take place against a backdrop of a world full of poverty, corruption, bureaucracy, and the opportunism displayed by cynical businessmen and officials in wartime India. Narayan manages to be serious and comic throughout the novel; he also alternates details of everyday life in Malgudi with moments where readers view the workings of Margayya’s mind. The critic William Walsh writes that the novel ‘‘has an intricate and silken organization, a scheme of composition holding everything together in a vibrant and balanced union.’’

The Guide (1958). The Guide is usually considered Narayan’s most accomplished novel. In this work, a former convict named Raju is mistaken for a holy man upon his arrival in Malgudi. Implored by the villagers to avert a famine, Raju is unable to convince them that he is a fraud. Deciding to embrace the role the townspeople have thrust upon him, Raju dies during a prolonged fast and is revered as a saint.

In a 1958 issue of the New Yorker, critic Anthony West praised The Guide as ‘‘the best of R. K. Narayan’s enchanting novels about the South Indian town of Malgudi and its people.... It is a profound statement of Indian realities.’’ The Malgudi novels as a whole are most often highly regarded. Critics often compare Narayan’s creation of Malgudi to William Faulkner’s fictional Yoknapatawpha County, and most agree with Charles R. Larson’s assessment: ‘‘While Faulkner’s vision remains essentially grotesque, Narayan’s has been predominantly comic, reflecting with humor the struggle of the individual to find peace within the framework of public life.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Narayan books often feature Hindu cultural practices. Using your library and the Internet, research the modern Hindu practices in India and write a paper summarizing your findings.

2. Narayan lived and wrote during a time of great change in India, as control of the government passed gradually from the British to the Indians themselves. To find out more about Britain’s long involvement in India, read Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (2000), a historical work by Lawrence James.

3. Chronologically, Narayan’s fiction takes up the major events of Indian history. Read one of his novels, then research and write a paper describing the historical context of the action in the novel.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Hariprasana, A. The World of Malgudi: A Study of R. K. Narayan’s Novels. New Delhi: Prestige Books, 1994.

Narayan, R. K. My Days: A Memoir. New York: Viking, 1974.

Ram, Susan, and N. Ram. R. K. Narayan: The Early Years: 1906-1945. New Delhi: Viking, 1996.

Walsh, William. R. K. Narayan. New York: Longman, 1971.

Periodicals

Berry, Ashok.‘‘Purity, Hybridity and Identity: R. K. Narayan’s The Vendor of Sweets’ WLWE 35 (1996): 51-62.

Mishra, Pankaj. ‘‘The Great Narayan.’’ New York Review of Books (February 22, 2001): 3.

West, Anthony. Review of The Guide. New Yorker (April 19, 1958).

Web sites

Bangla Literature in America. Memorable Books by R. K. Narayan. Retrieved May 28, 2008, from http://www.bangla.8k.com/exclusive/rk_books.html.

Brians, Paul. R. K. Narayan: The Guide: A Study Guide (1958). Washington State University at Pullman. Retrieved May 28, 2008, from http://www.wsu.edu:8080/~-brians/anglophone/narayan.html.

Datta, Nandan. ‘‘The Life of R. K. Narayan.’’ California Literary Review. Retrieved May 28, 2008, from http://calitreview.com/21.