World Literature

Sean O’Casey

BORN: 1880, Dublin, Ireland

DIED: 1964, Torquay, England

NATIONALITY: Irish

GENRE: Drama

MAJOR WORKS:

The Shadow of a Gunman (1923)

Juno and the Paycock (1924)

The Plough and the Stars (1924)

The Silver Tassie (1929)

Cock-a-Doodle Dandy (1949)

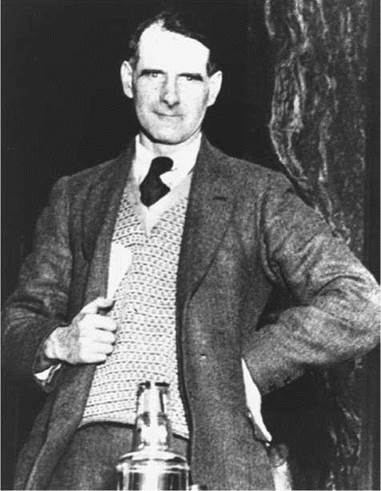

Sean O’Casey. O'Casey, Sean, photograph. AP Images.

Overview

One of the key dramatists of the early twentieth century, O’Casey was a prolific writer whose work displays a wide range of style and a willingness to experiment with form, language, and theme. A fervent advocate of the Irish labor movement, O’Casey rose to both prominence and controversy with his ‘‘Dublin Trilogy,’’ a series of plays focusing on the effects of the revolutionary struggle on the Dublin working class. Although he exiled himself to London in the midst of his career, his subject matter remains almost exclusively Irish.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

From Child of the Dublin Slums to Labor Leader. Sean O’Casey was born in 1880 in a slum neighborhood of Dublin, an area that in those days was as well known for its wretched conditions as for its colorful characters and speech. The importance of this locale for O’Casey should not be underestimated. Working as a common laborer, he became involved with the Irish nationalist movement, joining the Gaelic League, learning to speak, read, and write fluent Irish, and Gaelicizing his name from John Casey to Sean O’Cathasaigh, under which his writings of that time were published. The Gaelicizing of one’s name was and, to some extent, remains a symbol of resistance to British colonialism in Ireland and, indeed, O’Casey (as his name is most frequently rendered) soon became involved with the Irish struggle for freedom, joining the Irish Republican Brotherhood, an underground group devoted to ending British rule. At the age of thirty, O’Casey began to devote his energies to the Irish labor movement headed by Jim Larkin, helping to fight the appalling living and working conditions of his fellow workers. He served under Larkin as the first secretary of the Irish Citizen Army, wrote articles for the labor union’s newspaper, and helped organize a transport strike in 1913. He resigned his post, however, in 1914 when he was unable to prevent a rival group, the Irish Volunteers, from weakening the labor union. O’Casey viewed this group’s rebellion (alongside his own Irish Citizen Army) of 1916—the Easter Rising, which declared Ireland an independent republic and for which the leaders were executed—as ‘‘a great mistake,’’ seeing it as having robbed Ireland of its potential leadership. That leadership would be needed when, in 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty ended the several years of guerilla fighting that had been initiated by the Easter Rising, formally establishing an independent state of Ireland (and a still England- dependent state of Northern Ireland). Though distancing himself from the Irish Citizen Army, O’Casey continued to work as a journalist throughout this period.

A Journalist Turns to Drama, Questions “The Cause’’. In his midthirties O’Casey moved away from journalism and returned to a still earlier interest in drama. He had begun writing plays in 1918, submitting them to the Abbey Theatre, which was under the leadership of poet-dramatist William Butler Yeats and Lady Augusta Gregory. Those early plays were primarily naturalistic in theme and style, emphasizing the grimness and savagery of everyday life. It was not until 1923 that The Shadow of a Gunman, his fifth play, was accepted for production. Shadow is the tragedy of a poet and a peddler who becomes inadvertently involved in the guerrilla warfare of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in 1920s Dublin; it was to become the first part of O’Casey’s ‘‘Dublin Trilogy.’’ His next play, Juno and the Paycock, studied the effects of Dublin’s 1922 postwar disturbances—in large part a response of disgruntled IRA members to a peace with England that had left Northern Ireland under British rule—on a tenement family. Soon after Juno was completed, O’Casey began work on the last play in the trilogy, a drama focusing on the 1916 Easter week uprising itself. Named for the symbols of the Irish Citizen Army’s flag, The Plough and the Stars was a product of O’Casey’s disillusionment with nationalist politics. At its fourth performance at the Abbey, a riot broke out in the audience, partly because of the appearance of a prostitute in the second act, but primarily due to O’Casey’s unsympathetic treatment of the Republican cause. ‘‘For O’Casey,’’ writes critic Julius Novick, ‘‘the essential reality of war, revolutionary or otherwise, no matter how splendid the principle for which it is fought, is pain, and pain dominates the last half of The Plough and the Stars: fear, madness, miscarriage, and death, No wonder the Nationalists rioted when the play was new; they did not want to see the seamy side of their glorious struggle.’’

A Relocation to London: Abandoning Ireland? In 1926 O’Casey traveled to London to receive the Hawthornden Prize for Juno and the Paycock and decided to remain there with his new wife, Englishwoman Eileen Carey Reynolds. His next play, The Silver Tassie (1929), was the first he wrote outside his native land. Set in the Dublin slums, it studies the gruesome effects of the First World War. Critics had already noted O’Casey’s growing impatience with naturalism throughout his earlier work, and in the second act of The Silver Tassie he rejected stage naturalism altogether in favor of a more expressionistic style. Set behind the British front line, Act II used a combination of Cockney and Dublin soldiers, a mixture of realistic speech and stylized plainsong chant, and several other expressionistic techniques. The Abbey—Ireland’s premier drama stage—refused to produce the play, and Yeats’s public criticism of the play—calling it unconvincing and technically inferior—did tremendous damage to O’Casey’s reputation. The ensuing feud between the two lasted nearly seven years, until the drama was finally produced at the Abbey in 1935. By that time, O’Casey had severed all ties with the Abbey, leaving him without a theater workshop. His increasingly experimental dramas never received the preproduction treatment they needed, and commentators were frequently critical of his later work. Although he had begun experimenting with expressionistic techniques early in his career, it was not until Within the Gates (1933) that O’Casey created an entirely stylized piece. Throughout his later work O’Casey continued experimenting with both form and style, producing a number of plays (usually tragicomedies) that, according to Joan Templeton, often promoted the idea that ‘‘merriment and joy are the primary virtues in a world that has denounced them for too long.’’ The better known of those later works include Purple Dust (1942), Red Roses for Me (1943), and Cock-a-Doodle Dandy (1949). These later works were, of course, written under the shadow ofWorld War II, which gripped Europe and the world from 1939 through 1945, and they thus are attempts to trace out a way of being in a world that has been shattered. They never achieved the same critical success as O’sCasye’s earlier pieces, however.

In 1939, O’Casey had published the first book of his six-volume, partly fictional autobiography, each volume of which would cover about twelve years. He also began writing drama criticism for the journal Time and Tide around the same time, later claiming that he was ‘‘altogether too vehement to be a good critic.’’ Alongside the plays just mentioned, and several studies of common life in Ireland, the remainder of his creative life would be devoted to his autobiography, Mirror in My House and to criticism, until his death of a heart attack in Torquay, England, in 1964.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

O'Casey's famous contemporaries include:

Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980): One of the most popular and recognizable film directors of the twentieth century, Hitchcock displayed his mastery of the suspense genre in such works as Psycho, The Birds, Vertigo, and Rear Window.

Eugene O'Neill (1888-1953): Awarded the Nobel Prize for his plays, O'Neill was the first playwright to introduce American audiences to the techniques of realism pioneered by artists such as Henrik Ibsen and Anton Chekhov.

Fritz Lang (1890-1976): This innovative filmmaker was born in Austria but worked in the United States, successfully making the transition from silent to sound motion pictures. His expressive films often deal with the psychology of crime and death, and they set a high standard for the emotional depth and artistic potential for early cinema.

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939): An Irish poet and dramatist who won the Nobel Prize in 1923, Yeats was the driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival, and later served two terms as a senator in the Irish Senate, or Seanad Eireann.

Helen Keller (1880-1968): World famous for her triumphs over her disabilities, Keller went on to become an active and influential speaker and activist for progressive causes such as workers' and women's rights and antiwar movements.

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956): Journalist, essayist, satirist, and critic of American culture, Mencken delighted his readers with his witty barbs. He became nationally famous for his coverage of the Scopes trial (a legal case that pitted Darwinism and evolution theory versus creationism), which he dubbed the ''Monkey Trial.''

Works in Literary Context

For all the spontaneous gusto that characterized his writings, O’Casey was a deliberate and painstaking craftsman in the making of plays for stage performance, continually exploring the resources of the modern theater and seeking to expand the range and depth of the drama. He was also a literary artist—throughout a long career, he took his work seriously, searching for the right words in the right order and for the most effective means of organizing material. He was a poet by method as well as by nature, making extraordinary efforts over minor details, writing and rewriting many drafts of each play. His literary discrimination and self-criticism are plainly evident in his working methods, as shown by the successive manuscripts and typescript drafts of the plays among the papers that he left to his wife on his death.

Social Commentary. O’Casey was seldom content with social criticism or satire of things as they are: His imagination continually reached beyond—to things as they might be. Envisaging a future in which men and women will have more time and energy for leisure activities, he contemplated a new folk culture involving music, song, and dance, and attempted to realize something of this experience in his own work. The result is meant to have theatrical validity in its own right and is also intended as a yardstick by which the present—as portrayed in the plays—may be judged and found wanting. His preoccupations in this respect anticipated a good deal of modern literature and drama, particularly the plays of Arnold Wesker and John Arden. It is surprising that a number of theater critics who find such younger playwrights of interest because their work reflects contemporary concerns should often ignore the influence of O’Casey. At the same time, it may be contended that his dramatic practice looks backward as well as forward. His last plays, for example, are comparable to Shakespeare’s: in theme they explore the conflict between the generations and between past and present values, and, in technique, they display a similar interest in the creation of a more diversified form of stage play.

Politically, though O’Casey’s plays may be loosely equated with the drama of social protest or left-wing commitment, moral and aesthetic attitudes are always as important political points. Although he experienced many horrors and disappointments throughout a long and active life, the dominant impression put forward by the Irishman’s writings is of an expansive vision and optimism in regard to mankind, science, and the future. As such, his true affinities are with Walt Whitman, whom he admired, rather than with, say, contemporaries Franz Kafka and Samuel Beckett.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

O'Casey's plays became increasingly expressionistic as he grew older. Other examples of expressionistic plays include:

Murderer, The Hope of Women (1909), a drama by Oskar Kokoschka. Often called the first expressionist play, this brief work features simplified, almost mythical characters, and the declamatory dialogue that would come to characterize the expressionist movement.

The Hairy Ape (1922), a play by Eugene O'Neill. One of several expressionist plays written by O'Neill in the 1920s, this play follows the plight of a working-class man adrift in Manhattan, and condemns both rich capitalists and socialist labor organizers. In the end, the man can only find solace with a gorilla at the zoo.

A Dream Play (1907), a drama by August Strindberg. A precursor to both expressionism and surrealism, this play has been successfully revived many times. Strindberg was in the process of breaking from his earlier naturalist approach when he wrote this dream tale of the daughter of the goddess Indra descending to Earth to meet a variety of symbolic characters.

Works in Critical Context

O’Casey was a prolific writer whose published work reveals a wide range of subject matters and styles. Critics of his time first appreciated his nationalism and then decried his skepticism toward the results of that nationalism. Since then, readers have focused not only on his early Dublin Trilogy, but also on his cogent emotional responses to World War II and his keen studies of common life in Ireland.

The Dublin Trilogy and Beyond. Critic Kevin Sullivan has remarked that ‘‘O’Casey’s reputation for genius begins, and I think ends,’’ with his first three plays. He proceeds to explain that this belief ‘‘is the commonly accepted critical judgment on O’Casey which only his most fervent admirers ... would care to dispute.’’ In Robert Hogan’s critical view, the negative reception of O’Casey’s later plays may be attributed to most critics’ unquestioning acceptance of the belief that ‘‘when O’Casey left for England, he left his talent behind on the North Circular Road.’’ Yet Hogan himself has argued that ‘‘you can only prove the worth of a play by playing it,’’ and having staged or performed in five of O’Casey’s later plays, he asserts that ‘‘most of O’Casey’s late work is eminently, dazzlingly good.’’

Legacy. O’Casey’s style and technique, constantly adapted and modified to present historically relevant themes in new and theatrically exciting ways, may often be uneven in quality, but there is a continual striving for variety and originality. The importance of such formal experimentation and the reasons for its critical neglect were succinctly expressed in the playwright’s obituary in the London Times on, September 21, 1964:

There was a time when the general public eagerly expected him to go on working indefinitely in the style of his famous Dublin trilogy.... He insisted on his right as an artist to develop in his own way. Neither politically nor stylistically were the developments in his middle period popular. The consequence was that when he had mellowed politically and critics were in a position to appreciate that his real preoccupation as a dramatist had not been with the destruction of society but with the destruction of dramatic realism it was too late. O’Casey could no longer count on getting the plays he continued to publish adequately performed, if at all.

That his primary aesthetic aim was ‘‘the destruction of dramatic realism’’ and the creation of a more diverse and theatrically exciting form of drama now seems indisputable. To what extent he succeeded in that aim remains for future generations to determine.

Responses to Literature

1. Summarize the focus of Juno and the Paycock. What do you feel accounts for its enduring popularity? Why do you think the musical adaptation flopped?

2. Describe O’Casey’s role in the foundation and support of the Abbey Theater. How does his legacy compare to that of W. B. Yeats, the theater’s most famous member?

3. Sean O’Casey was one of several Irish writers who helped revive interest in Irish myths and legends. Research Irish mythology, then write about why you think the old tales would have been important to Irish citizens in the early twentieth century. What legends specifically would have spoken to modern Irish revolutionaries?

4. O’Casey’s play Red Roses for Me is set during the 1913 Dublin Lockout. Research the event and consider the literary techniques O’Casey uses to bring it into focus. In what ways does his writing—in its structure, in its diction, in its use of formal stylistic elements—evoke the spirit of that moment?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Armstrong, William A. Sean O’Casey. New York: Longman, 1967.

Benstock, Bernard. Sean O’Casey. Cranbury, N. J.: Bucknell University Press, 1970.

Hacht, Anne Marie, ed. ‘‘Red Roses for Me. ’’Drama for Students. Vol. 19. Detroit: Gale, 2004.

Kilroy, Thomas, ed. Sean O’Casey: A Collection of Critical Essays, Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall, 1975.

O’Casey, Eileen. Cheerio, Titan: The Friendship between George Bernard Shaw and Sean O’Casey. New York: Scribner, 1989.

Schrank, Bernice. Sean O’ Casey: A Research and Production Sourcebook. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1996.

Weintraub, Stanley, ed.Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 10: Modern British Dramatists, 1900-1945. Detroit: Gale Group, 1982.