World Literature

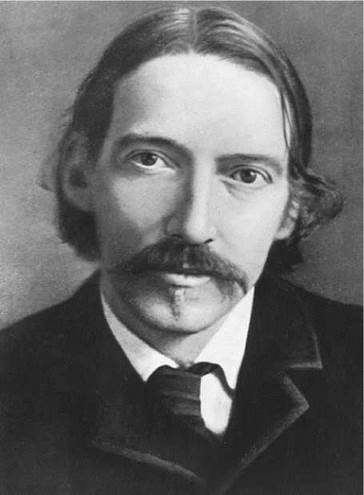

Robert Louis Stevenson

BORN: 1850, Edinburgh, Scotland

DIED: 1894, Vailima, Samoa

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

New Arabian Nights (1882)

Treasure Island (1883)

Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886)

Kidnapped (1886)

In the South Seas (1896)

Robert Louis Stevenson. Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Overview

The life of Robert Louis Stevenson was regarded by his public, his friends, and his biographers to be as thrilling as the adventures in the stories he wrote. Stevenson began his career primarily as an essayist and travel writer, though he soon moved on to short fiction, and after the publication of Treasure Island in 1883, the novel was his preferred form. He wrote memorable poetry and forgettable plays, but it was short fiction, particularly his famous Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), that gained him a large adult readership.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Sickly Childhood in Edinburgh. Robert Louis Stevenson was born to Thomas and Margaret Isabella Balfour Stevenson in Edinburgh on November 13, 1850. From birth he was sickly, and throughout much of his childhood he was attended by his faithful nurse, Alison Cunningham, known as Cummy in the family circle. She told him morbid stories, read aloud to him Victorian penny-serial novels, Bible stories, and the Psalms, and drilled the catechism into him—all with his parents’ approval. Robert’s father Thomas Stevenson was quite a storyteller himself, and his wife doted on their only child, sitting in admiration while her precocious son expounded on religious doctrine. Stevenson later reacted against the morbidity of his religious education and to the stiffness of his family’s middle-class values, but that rebellion would come only after he entered Edinburgh University.

An Indifferent Student Sets Out to Write. In November 1867 Stevenson entered Edinburgh University, where he pursued his studies indifferently until 1872. Instead of concentrating on academic work, he busied himself in learning how to write, imitating the styles of William Hazlitt, Sir Thomas Browne, Daniel Defoe, Charles Lamp, and Michel de Montaigne. By the time he was twenty-one, he had contributed several papers to the short-lived Edinburgh University Magazine, the best of which was a fanciful bit of fluff entitled ‘‘The Philosophy of Umbrellas.’’ Edinburgh University was a place for him to play the truant more than the student. His only consistent course of study seemed to have been of bohemia: Stevenson adopted a wide-brimmed hat, a cravat, and a boy’s coat that earned him the nickname of Velvet Jacket, while he indulged a taste for haunting the byways of Old Town and becoming acquainted with its denizens.

On a trip to a French artists’ colony in July 1876 with his cousin Bob, Stevenson met Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne, a married woman, an American, and ten years Stevenson’s senior. The two were taken with one another, and Osbourne said she would be getting a divorce from her husband.

Impetuous Transatlantic Pursuit of a Married Woman. In August 1879, Stevenson received a cablegram from Fanny Osbourne, who by that time had rejoined her husband in California. With the impetuosity of one of his own fictional characters, Stevenson set off for America to find her. On August 18, he landed, sick, nearly penniless, in New York. He was most likely suffering from tuberculosis (the disease was commonly called ‘‘consumption’’ at the time, and it was often misdiagnosed), which was incurable. From there he took an overland train journey in miserable conditions to California, where he nearly died. After meeting with Fanny Osbourne in Monterey, and no doubt depressed at the uncertainty of her divorce, he went camping in the Santa Lucia mountains, where he lay sick for two nights until two frontiersmen found him and nursed him back to health. Still unwell, Stevenson moved to Monterey in December 1879 and thence to San Francisco, where he was ever near to death, continually fighting off his illness (people with tuberculosis often had periods of relative wellness interspersed with bouts of sickness). When Stevenson had left Scotland so abruptly, this had temporarily estranged him from his parents. They were also upset about his relationship with a married woman. However, hearing of their son’s dire circumstances, they cabled him enough money to save him from poverty. Fanny Osbourne obtained her divorce from her husband, and she and Stevenson were married on May 19, 1880, in San Francisco.

Tuberculosis, Travel, and Writing While in Bed. In the next seven years, 1880 to 1887, Stevenson did not flourish as far as his health was concerned, but his literary output was prodigious. Writing was one of the few activities he could do while confined to bed because of hemorrhaging lungs (a common tuberculosis symptom). During this period, he wrote some of his most enduring fiction, notably Treasure Island (1883), Kidnapped (1886), Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), and The Black Arrow (1888). He was also busy writing essays and collaborating on plays with W. E. Henley, the poet, essayist, and editor who championed Stevenson in London literary circles and who became the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island.

This was also a period of much traveling. His and Fanny’s various temporary residences in England, Switzerland, and southern France had more to do with his probable tuberculosis than with his love for travel. The main accepted treatment for tuberculosis at the time was the seeking of ‘‘healthy air,’’ although doctors disagreed about what made air healthy. Switzerland was a popular destination for tuberculosis patients because of its clear mountain air. It was at Braemar in Scotland that Treasure Island was begun, sparked by a map that Stevenson had drawn for the entertainment of his twelve-year-old stepson Lloyd Osbourne. Stevenson had quickly imagined a pirate adventure story to accompany the drawing, and a friend arranged for it to be serialized in the boys’ magazine Young Folks, where it appeared from October 1881 to January 1882. By the end of the 1880s, it had become one of the most popular and widely read books of the period.

Bound for the South Seas. In 1888, Stevenson made a drastic decision. In a letter to his friend Baxter in May of 1888, he wrote that he would be taking a South Seas cruise, one that he expected to heal him emotionally as well as physically: ‘‘I have found a yacht, and we are going the full pitch for seven months. If I cannot get my health back... ’tis madness; but of course, there is the hope, and I will play big.’’ Sea air was also considered beneficial to people suffering from tuberculosis.

South Pacific Journey and a Home in Samoa. The Stevenson party—including Stevenson, his wife, his stepson, and his mother—chartered the yacht Casco and sailed southwest from San Francisco to the Marquesas Islands, the Paumotus, and the Society Islands, and thence northward from Tahiti to the Hawaiian Islands by December of 1888. They camped awhile in Honolulu, giving Stevenson time to visit the Molokai leper settlement and to finish his novel The Master of Ballantrae (1889). In June 1889 they set out southwest from Honolulu for the Gilbert Islands aboard the schooner Equator. From there in December 1889 the Stevensons traveled to the island of Upolu in Samoa. By that time Stevenson realized that he was too ill to return to Scotland, despite his friends’ urgings and his own homesickness; each time that he ventured far from the equator he fell sick. In October of 1890, the Stevenson party returned to Samoa to settle, after a third cruise that had taken them to Australia, the Gilberts, the Marshalls, and some of the more remote islands in the South Seas. The Samoan islands had been claimed by Great Britain, Germany, and the United States, by this time, and Stevenson developed a lively disdain for their colonial presences—in many cases taking much more the part of the Samoans, whom he saw as unjustly governed in slapdash fashion by slovenly rulers.

Death at the Height of His Power. While he lived in the Pacific, Stevenson kept up his usual impressive literary output, but in the last two years of his life his letters to his friends in Great Britain increasingly revealed a longing for Scotland and the frustration he felt at the thought of never seeing his homeland again. To S. R. Crockett he wrote, ‘‘I shall never see Auld Reekie. I shall never set my foot again upon the heather. Here I am until I die, and here will I be buried. The word is out and the doom written.’’ It may have been this preoccupation with Scotland and its history that made Weir of Hermiston so powerful a tale. With its theme of filial rebellion, and its evocation of Scotland’s topography, language, and legends, it is a masterly fragment and the most Scottish of all his works. Records of a Family of Engineers, a biographical work that recounts his grandfather’s engineering feats, reveals, too, that Stevenson was trying to find a bridge back to his own family and finally coming to terms with his earlier rejection of the engineering profession. In Records of a Family of Engineers he depicts his grandfather as a scientist-artist, linking his own growing objectivity in his style of writing to the technical yet imaginative work of his forebears. Increasingly Stevenson’s art embraced more of the everyday world and drew on his experiences in the South Seas for its strength. When he died of a stroke on December 3, 1894, in his house at Vailima, Samoa, he was at the height of his creative powers.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Stevenson's famous contemporaries include:

Queen Victoria (1819-1901): The ruler of the United Kingdom (1837-1901) and the first Empress of India; the period of her reign is known as the Victorian era.

Richard Francis Burton (1821-1890): An English explorer and writer, Burton was best known for his travels in Asia and Africa, especially his expedition to find the source of the Nile River.

Mark Twain (1835-1910): An American humorist and satirist born Samuel Clemens, Twain is best known for his novels The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

Henry James (1843-1916): An American novelist who eventually took a British passport, James was one of the founders of realism in fiction.

Sigmund Freud (1858-1939): The Austrian psychologist who founded the school of psychoanalysis, Freud pioneered the concept of the division of human consciousness into an id, ego, and superego.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930): A Scottish author best known for creating the character of Sherlock Holmes.

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936): A British writer and poet, Kipling is the author of The Jungle Book and the first English-language writer to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Stevenson's later novels and stories examine moral dilemmas presented in an atmosphere imbued with mystery and horror. They include certain recurring themes, such as those of the divided self and the nature of evil. Here are some other works that deal with the theme of the divided self:

The Invisible Man (1897), a novel by H. G. Wells. This novel centers around a scientist who discovers a formula for invisibility but becomes mentally unstable as he copes with the problems of his condition while attempting to become visible again.

Seize the Day (1956), a novella by Saul Bellow. This novella chronicles a day in the life of Tommy Wilhelm, born Wilky Adler, a character who embodies the notion of the divided self.

Psycho (1960), a film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. This suspense/horror film explores the moral dimensions of crime and murder.

Works in Literary Context

In ‘‘A Penny Plain and Two-pence Coloured’’ (1884), Stevenson recounts how the seeds of his own craft were sown in childhood when he purchased Skelt’s Juvenile Drama—a toy set of uncolored or crudely colored cardboard characters (hence the title of Stevenson’s essay) who were the principal actors in a usually melodramatic adventure. Stevenson maintained that his art, his life, and his mode of creation were all in some part derived from the highly exaggerated and romantic world he had inherited from Skelt. Indeed, he saw himself as the literary descendant of British Romantic author Sir Walter Scott. The best storytelling, he felt, had the ability to whisk readers away from themselves and their circumstances.

Daydreams and Nightmares, but Without Escapism. Although much of Stevenson’s fiction was aimed at entertainment, his later novels and stories cannot be easily categorized as escapist. In one sense, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde can be taken as a satire of the times in which a respectable and educated man is forced so to repress his animal nature as to turn it into an uncontrollably violent beast. Yet there is much in the tale that does not allow such an interpretation to go unqualified. There is a wildness in Hyde that does not really lend itself to possible accommodations to a moral world, even one more liberal and permissive than that of the 1880s. Furthermore, as it progresses the story seems preoccupied less with social and moral alternatives than with the inevitable progress into vice. Part of the appeal of the tale is, as the title suggests, its strangeness. It has its own obsessive logic and momentum that sweep the reader along. Thus, though various morals can be drawn from it (warnings against intellectual pride, hypocrisy, and indifference to the power of the evil within), the continuing attraction of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is perhaps the exact reverse of that of Treasure Island: One is an almost perfect literary rendition of a child’s daydream of endless possibilities, the other of an adult’s nightmare of disintegration. In both cases, whether gleefully or frightfully ensconced in the realm of the fantastic, Stevenson’s work is if not precisely escapist then at least elsewhere-directed.

Works in Critical Context

Pinnacle to Nadir, and Back: A Treasure Not Just for Children. At the time of his death in Samoa in 1894, Robert Louis Stevenson was regarded by many critics and a large reading public as the most important writer in the English-speaking world. ‘‘Surely another age will wonder over this curiosity of letters,’’ wrote Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch at the time, ‘‘that for five years the needle of literary endeavor in Great Britain has quivered toward a little island in the South Pacific, as to its magnetic pole.’’ Critics as demanding as Henry James and Gerard Manley Hopkins agreed on Stevenson’s importance. This idealized portrait was attacked in the 1920s and 1930s by modernist writers who labeled his prose as imitative and pretentious and who made much of Stevenson’s college- day follies. In the 1950s and 1960s, however, his work was reconsidered and finally taken seriously by the academic community. Outside of academia, Treasure Island and Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde continue to be widely read over a century after they were first published, and show promise of remaining popular for centuries to come. As such, they have influenced generations of writers, including Ernest Hemingway, who noted that Stevenson’s Treasure Island was one of his favorite books as a child. In this vein, R. H. W. Dillard has remarked, ‘‘When future scholars manage to see past their blind spot concerning the influence of children’s books on adult literature and come to look for (apart from the usual suspects) the sources of the best twentieth-century prose, they may well find to be more important than they currently imagine.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Treasure Island tops the list of children’s classics, and many famous authors have noted that the book was one of their favorites in their youth. It has been adapted for film numerous times, and its characters are generally familiar even to those who have never read the book. Read Treasure Island, then write a paper examining whether or not the youth of today would find the story and the style as gripping as readers of the past. Why or why not?

2. Stevenson’s life was given nearly as much attention as his writings. Do you think a writer’s life should be a focus of the audience’s attention, or should readers and critics look only at the words and stories instead? Have you found that learning about authors’ lives adds to or takes away from your understanding and appreciation of their works?

3. Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll character has been used in many movies since the book was published. What is the attraction of this character? Is it simply an entertaining notion, or does Dr. Jekyll have an enduring appeal because his story tells us something deeper about our modern selves?

4. Many of Stevenson’s writings chronicled his travels and personal adventures. Today, blogging is a widely used forum for this same kind of writing, and bloggers have the advantage of being able to publish their works instantly, often from faraway places. Does the immediacy of blogging add to or take away from this form of writing? Do blogs today have the same quality of writing and insight as the travel writings of authors like Stevenson?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Balfour, Graham. The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson. New York: Scribners, 1901.

Calder, Jenni. RLS: A Life Study. London: Hamilton, 1980.

Chesterton, G. K. Robert Louis Stevenson. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1927.

Daiches, David. Robert Louis Stevenson. Norfolk, Conn.: New Directions, 1947.

Dillard, R. H. W. ‘‘Introduction,’’ in Treasure Island. New York: Signet Classics, 1998.

Eigner, Edwin M. Robert Louis Stevenson and Romantic Tradition. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1966.

Ferguson, De Lancey, and Marshall Waingrow, eds. R. L. S.: Stevenson’s Letters to Charles Baxter. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1956.

Furnas, J. C. Voyage to Windward: The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson. New York: Sloane, 1951. Hammerton, J. A., ed. Stevensoniana. Edinburgh: Grant, 1910.

Kiely, Robert. Robert Louis Stevenson and the Fiction of Adventure. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1965.

Prideaux, W. F. A Bibliography of the Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, revised edition, ed. and supp. Mrs. Luther S. Livingston. London: Hollings, 1918.

Smith, Janet Adam, ed. Henry James and Robert Louis Stevenson: A Record of Friendship and Criticism. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1948.

________. Robert Louis Stevenson. London: Duckworth, 1947.

Swearingen, Roger G. The Prose Writings of Robert Louis Stevenson: A Guide. Hamden, Conn.: Archon, 1980.