World Literature

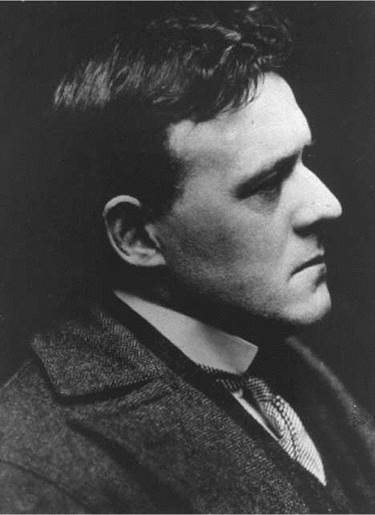

Hilaire Belloc

BORN: 1870, Le Celle St. Cloud, France

DIED: 1953, King’s Land, England

NATIONALITY: British, French

GENRE: Nonfiction, fiction, poetry

MAJOR WORKS:

The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts (1896)

The Path to Rome (1902)

The Servile State (1912)

A Companion to Mr. Wells’s ‘‘Outline of History’’ (1926)

Essays of a Catholic Layman in England (1931)

Hilaire Belloc. Belloc, Hilaire, photograph. The Library of Congress.

Overview

Hilaire Belloc was one of the most controversial and accomplished men of letters of early twentieth-century England. He was a productive historian, novelist, and essayist as well as a poet, noted for his light verse for children. More importantly, Belloc was recognized as an outspoken proponent of radical social and economic reforms, all grounded in his vision of Europe as a ‘‘Catholic society.’’

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Born into Political Instability. The son of a wealthy French father and English mother, Belloc was born Joseph Hilaire Pierre Sebastien Rene Swanton Belloc in La Celle St. Cloud, France, a few days before the Franco-Prussian War, also known as the 1870 War, broke out. Tensions between the two sides, France and German-backed Prussia, revolved around the empty Spanish throne following the deposition of Isabella II in 1868. The Belloc family fled to England at the news of the French army’s collapse. During the siege of Paris and its aftermath, the Belloc home was occupied by German troops who vandalized the furniture and family pictures, cut down the chestnut grove, and left Belloc with a lifelong distaste for ‘‘the Prussian,’’ which corresponded to his enthusiasm for the Latin cultures. It also perhaps encouraged his tendency toward racial hostilities and overgeneralizations.

Catholic Education. After the death of Belloc’s father in 1872, the family again took up residence in England, where Belloc was raised and received a Catholic education, notably at Cardinal John Henry Newman’s Oratory School near Birmingham, where he won many academic prizes and came to the attention of Newman himself.

Five Unsettled Years. After Belloc left the Oratory School in 1887, he decided to garner a larger experience of life than that afforded by the English academic world. He began, and soon abruptly ended, careers in the French navy, as a land agent on the duke of Norfolk’s estate, and as an architectural draftsman. The five unsettled years after he left school provided him with experience from which he drew—as much as from his more academic learning—for his writing throughout his life. During these years Belloc also cultivated the acquaintance of Cardinal Manning, another English convert to Catholicism, but of a far more militant stamp than the reserved and saintly Newman. Manning’s polemical stance and vision of a Catholic society were a great influence on the tone of Belloc’s writing and the social and religious ideals behind much of his work.

Catholic Advocacy. Belloc’s career as an advocate of Catholicism first attracted wide public attention in 1902 with The Path to Rome, perhaps his most famous single book, in which he recorded the thoughts and impressions that came to him during a walking trip through France and Italy to Rome. In addition to its infusion of Catholic thought, the work contains what later became acknowledged as typically Bellocian elements: rich, earthy humor, an eye for natural beauty, and a meditative spirit.

Light Verse and Popular Success. By the mid-1890s, Belloc had married and, through the influence of his sister Marie Belloc Lowndes, a noted writer, began writing for various London newspapers and magazines. His first book, Verses and Sonnets, appeared in 1896, followed in the same year by The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts, which satirized moralistic verse for children and proved immensely popular. Illustrated with superb complementary effect by Belloc’s friend Basil T. Blackwood, The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts, according to critics, contains much of the author’s best light verse, as do such later collections as More Beasts (for Worse Children) (1897), The Modern Traveller (1898), and Cautionary Tales for Children (1907). An impulsive man who seldom lived in any one place for more than a few weeks and whose frequent trips to the Continent proved a constant drain on his financial resources, Belloc welcomed the popular success of his verse collections.

A Brilliant Champion of Roman Catholicism. In 1892, Belloc continued his studies at Balliol College, Oxford, where he gained a reputation as a brilliant student, a skilled debater, and an aggressively outspoken champion of Roman Catholicism. Prejudice against Belloc’s Catholicism led to his being rejected in his bid for a history fellowship, an experience that intensely embittered him. Through this rejection Belloc came to hate university dons in general, later directing many satiric attacks against them, portraying them as smug, pretentious defenders of privilege.

In 1899 Belloc began a series of biographies, which included two French revolutionaries Danton (1899) and Robespierre (1901) and many eminent literary and political figures of France and England. In 1902 he published Path to Rome.

Belloc and Chesterton. For the next thirty years, Belloc enjoyed his widest fame and influence. During these years Belloc also became very active in political life. He became a British citizen in 1902, and in 1906 he was elected to Parliament. In 1910 he abandoned political office for journalism, which he felt was a more effective means of achieving reform. When Belloc met G. K. Chesterton, Belloc found a talented illustrator of his books, a friend, and a man who shared and publicly advocated many of his own religious and political views. Anti-industrial and antimodern in much of their advocacy, the two were jointly caricatured in print by George Bernard Shaw as ‘‘the ChesterBelloc,’’ an absurd pantomime beast of elephantine appearance and outmoded beliefs. Both, according to Shaw and other adverse critics, had a passion for lost causes.

Three Acres and a Cow. In 1912 Belloc published The Servile State, which outlined his antisocialist and anticapitalist philosophy of distributism. Belloc called for a return to familial self-sufficiency through the widespread restoration of private property; according to his prescription, which has been described by many critics as at best quaint and at worst ridiculously impractical, every family should own three acres and a cow. His views were shared by G. K. Chesterton, and together they founded the political weekly New Witness to press forward the fight for reform.

Eye Witness. The ChesterBelloc’s political ideas were also expounded in the Eye Witness, a weekly political and literary journal edited by Belloc, which became one of the most widely read periodicals in prewar England. Belloc attracted as contributors such distinguished authors as Shaw, H. G. Wells, Maurice Baring, and Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch. In addition, he and his subeditor, Cecil Chesterton, involved the Eye Witness in a political uproar in 1912 when they uncovered the Marconi scandal, in which several prominent government officials used confidential information concerning impending international business contracts in order to speculate in the stock of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company.

Belloc had established himself as a polemicist who could write forceful and convincing essays on nearly any subject, in a prose style marked by clarity and wit. This reputation reached its zenith in 1926 when, in A Companion to Mr. Wells’s ‘‘Outline of History’’, he attacked his longtime opponent’s popular book as a simpleminded, nonscientific, anti-Catholic document. A war of mutual refutation ensued, fought by both writers in the pages of several books and essays.

Decline of Influence. His exchange with Wells was Belloc’s last major triumph as a man of letters, as throughout the 1920s and 1930s his own ideas were increasingly brushed aside by a public uninterested in seeing Britain return to Catholic values and medieval social structures. Further, in light of the rise to power of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in Europe, a growing number of readers were offended by Belloc’s casual use of anti-Semitic remarks in his works and his view of Mussolini as one of Europe’s great warrior-kings reborn. Embittered that his opinions were no longer taken seriously and that his creative gifts were diminishing, Belloc spent the last years of his career writing histories and biographies, which have been described by Wilfrid Sheed as ‘‘a ream of unsound, unresearched history books blatantly taking the Catholic side of everything.’’ In the early 1940s, after authoring over 150 books, Belloc was forced into retirement by old age and a series of strokes. He spent the last ten years of his life in quiet retirement at his longtime home in rural Sussex, King’s Land, and died in 1953.

Works in Literary Context

In his time, Hilaire Belloc enjoyed the same popularity with readers as George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and G. K. Chesterton. Belloc’s literary reputation is currently in decline; yet during his lifetime he achieved great acclaim for his writings in a wide variety of genres. His contemporary fame was linked to that of Chesterton, and the two of them attained major status in British letters during the period prior to World War I. Belloc’s career was both lengthy and prolific.

Forms, Themes, and Style. Belloc turned his hand to virtually every form of literature. He wrote poetry, fiction, history, travel pieces, and works on topography, as well as articles and essays in a wide variety of modes including ridicule, parody, satire, and logical argumentation. Although his first love was poetry, the essay was his daily occupation. His themes are diverse: God, nature, society, culture, literature, politics, and history. His style is clear, concise, and profound whether he is being playful and charming, angry and bitter, or humorous and funny.

Articulating Unpopular Opinions. An impassioned controversialist and a brilliant talker, Belloc enjoyed espousing unpopular opinions and telling the British public, especially the intellectuals, about the folly and ignorance of their cherished views. However erratic his own views were, Belloc delivered them, in person or in print, with such eloquence and fluent wit that people were usually eager to hear him out.

It is one of the ironies of literary reputation that, in the vast body of Belloc’s work, the verses for children that seemed to his contemporaries such a minor and ephemeral part of his achievement, and that were never labored over and polished as his adult poetry was, seem to be the only aspect of his work that has retained its appeal. In contrast with his ‘‘serious’’ books, Belloc’s children’s verse has given pleasure and amusement to generations of readers and seems likely to continue to do so. The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts (1896) and Cautionary Tales for Children, Designed for the Admonition of Children Between the Ages of Eight and Fourteen Years (1908), along with their sequels, are masterpieces of nonsense and continue to delight children in contemporary illustrated editions.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Belloc's famous contemporaries include:

George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950): Irish playwright who won both the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1925 and an Academy Award in 1938.

H. G. Wells (1866-1946): English writer who is best known today for his pioneering science fiction novels. During his lifetime, he was also an outspoken advocate of socialism.

G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936): Influential English writer who was widely praised by his contemporaries.

Winston Churchill (1874-1965): Prominent British statesman of the Conservative Party who led Great Britain during World War II.

Antoine de Saint Exupery (1900-1944): French aviator and writer best known for The Little Prince (1943).

Works in Critical Context

Belloc is an author whose writings continue to draw either the deep admiration or bitter contempt of readers. Many critics have attacked Belloc’s prescriptive polemical works for their tone of truculence and intolerance and, especially, for recurrent elements of anti-Semitism, but they also have joined in praise of his humor and poetic skill, hailing Belloc as the greatest English writer of light verse since Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear.

Poet of Light Verse. While Belloc’s political and social views have proven unpopular, critics have highly praised the author’s light verse, with W. H. Auden going so far as to state of Belloc that ‘‘as a writer of Light Verse, he has few equals and no superiors.’’ In his widely known cautionary verse for children, Belloc assumed the perspective of a ridiculously stuffy and pedantic adult lecturing children on the inevitable catastrophes that result from improper behavior. Among his outstanding verses of this type are ‘‘Maria Who Made Faces and a Deplorable Marriage,’’ ‘‘Godolphin Horne, Who Was Cursed with the Sin of Pride, and Became a Bootblack,’’ and ‘‘Algernon, Who Played with a Loaded Gun, and, on Missing His Sister, Was Reprimanded by His Father.’’ ‘‘Unlike Lear and Carroll, whose strategy was to bridge the gulf between adults and children,’’ Michael Markel has written, ‘‘Belloc startled his readers by exaggerating that gulf. Belloc’s view of children did not look backward to the Victorian nonsense poets, but forward to the films of W. C. Fields.’’ Like his children’s verse, Belloc’s satiric and noncautionary light verse is characterized by its jaunty, heavily rhythmic cadences and by the author’s keen sense of the absurd, as reflected in ‘‘East and West’’ and in ‘‘Lines to a Don,’’ which skewers a ‘‘Remote and ineffectual Don / That dared attack my Chesterton.’’

Hilaire Belloc is chiefly remembered for his controversial political opinions, often belligerent character, and strong allegiance to the Catholic Church. His deep feelings about the important political and social issues of his day manifest themselves in most of his works. Although he has been criticized because of his tendency to sermonize, the sheer number of his published works, their versatility, and their stirring and often humorous style are impressive.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

The mockery of human pretensions through the use of nonsense verses about animals were a central aspect of Belloc's children's stories. Here are some other works of children's stories with similar themes:

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), a children's book by Lewis Carroll. This classic children's book follows Alice's adventures in a topsy-turvy world populated by talking animals and outlandish characters.

Ogden Nash's Zoo (1986), a collection of children's poems by Ogden Nash. This book consists of short, nonsensical poems about animals.

Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events (2004), a film directed by Brad Silberling. This is a film adaptation of the Lemony Snicket series of books that follows the adventures of three children through absurdist storylines

Responses to Literature

1. Belloc’s popularity waned after World War II partly because of the unpopularity of his anti-Semitism in the wake of the Holocaust. As a class, discuss why authors lose their popularity and influence when events lead to a major shift in public opinion. Do you think readers should turn away from writers who have expressed unpopular opinions, or should they instead look past those opinions for the merit in the writer’s work?

2. Many of Belloc’s essays and historical writings were designed to promote his program of Distributism. Using the Internet and your library resources, research the basic principles of Distributism. In your research, state whether you think Distributism would work in today’s capitalistic world.

3. Belloc’s most enduring legacy is his children’s literature. After reading several of Belloc’s stories, write your own children’s story that uses Belloc’s combination of adult wit and absurdist children’s storyline.

4. Belloc often used his travel, literary, and historical essays to make a point about current political issues. Write an essay about a historical figure, author, or personal trip designed to prove a point about a controversial political topic.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Corrin, Jay P. G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc: The Battle against Modernity. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1981.

Feske, Victor. From Belloc to Churchill: Private Scholars, Public Culture, and the Crisis of British Liberalism, 1900-1939. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Hamilton, Robert. Hilaire Belloc: An Introduction to His Spirit and Work. London: Douglas Organ, 1945.

Jebb, Eleanor, and Reginald Jebb. Belloc, the Man. Westminster, Md.: Newman Press, 1957.

Lowndes, Marie Belloc. “I, Too, Have Lived in Arcadia’’. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1942.

McCarthy, John P. Hilaire Belloc: Edwardian Radical. Indianapolis: Liberty Press, 1973.

Morton, J. B. Hilaire Belloc: A Memoir. New York: Sheed & Ward, 1955.

Raymond, Las Vergnas. Chesterton, Belloc, Baring. New York: Sheed & Ward, 1938.

Speaight, Robert. The Life of Hilaire Belloc. London: Hollis & Carter, 1957.

Wilhelmsen, Frederick. Hilaire Belloc: No Alienated Man. New York: Sheed & Ward, 1953.

Wilson, A. N. Hilaire Belloc. London: Hamilton, 1984.

Woodruf, Douglas, ed. For Hilaire Belloc: Essays in Honor of His 71st Birthday. New York: Sheed & Ward, 1942.