World Literature

William Butler Yeats

BORN: 1865, Dublin

DIED: 1939, Roquebrune, France

NATIONALITY: Irish

GENRE: Poetry, plays, essays

MAJOR WORKS:

The Wind Among the Reeds (1899)

The Wild Swans at Coole (1917)

A Vision (1925)

The Tower (1928)

The Winding Stair and Other Poems (1933)

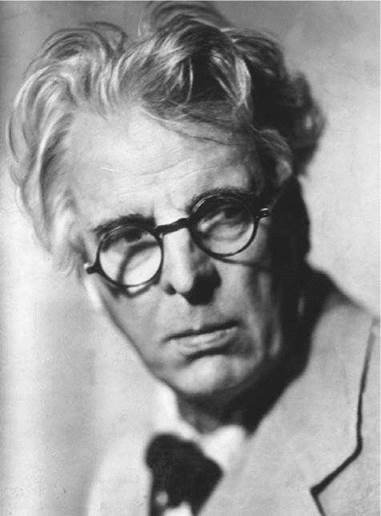

William Butler Yeats. Howard Coster / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Overview

William Butler Yeats was an Irish poet and playwright closely associated with Irish nationalism. He received the 1923 Nobel Prize in Literature ‘‘for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation,’’ as the citation read.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

An Anglo-Irish Protestant Upbringing. Yeats belonged to the Protestant, Anglo-Irish minority that had controlled the economic, political, social, and cultural life of Ireland since at least the end of the seventeenth century. Most members of this minority considered themselves English people who merely happened to have been born in Ireland, but Yeats staunchly affirmed his Irish nationality. Although he lived in London for fourteen years of his childhood (and kept a permanent home there during the first half of his adult life), Yeats maintained his cultural roots by featuring Irish legends and heroes in many of his poems and plays. He was equally firm in adhering to his self-image as an artist.

Yeats was born in the Dublin suburb of sandymount on June 13, 1865. He was the oldest of the four surviving children of the painter-philosopher John Butler Yeats and his wife, Susan Pollexfen Yeats. The poet was proud to belong to the Anglo-Irish Protestant minority in both strains of his blood. His mother’s family were ship owners and millers in and about Sligo. The hills and lakes and fens about the busy West of Ireland seaside town became Yeats’s spiritual home in childhood and remained so all his life. The young Yeats was dreamy and introspective but by no means housebound. He rode about the Sligo countryside on a red pony and began to immerse himself in the fairy lore of the local peasants. His formal education, however, was not so enriching. He was so slow in learning to read that he was thought to be simple

The Influence of Maud Gonne on Yeats’s Nationalism and Spiritualism. The year 1885 was important in Yeats’s early adult life, marking the first publication of his poetry (in the Dublin University Review) and the beginning of his important interest in the occult. At the end of 1886, Yeats moved to London, where he composed poems, plays, novels, and short stories—all with Irish subjects, characters, and scenes. In addition, he wrote book reviews, usually on Irish topics. The most important event in Yeats’s life during these London years, however, was his acquaintance with Maud Gonne, a beautiful, prominent young woman passionately devoted to Irish nationalism—the establishment of an Irish nation independent of British rule. Irish nationalism had grown in fits and starts since 1800, when Ireland was forcefully joined with Great Britain in the British Act of Union. In the 1880s and 1890s, Irish politician Charles Stewart Parnell managed to introduce two bills on Irish Home Rule in British Parliament, but both were defeated. It became clear to the Irish that they would not find independence through negotiation alone.

Yeats soon fell in love with Gonne and wrote many of his best poems about her. With Gonne’s encouragement, Yeats redoubled his dedication to Irish nationalism and produced such nationalistic plays as The Countess Kathleen, dedicated to Gonne, and Cathleen ni Houlihan (1902), which featured Gonne as the personification of Ireland.

Gonne also shared Yeats’s interest in occultism and spiritualism. In 1890 he joined the Golden Dawn, a secret society that practiced ritual magic. The society offered instruction and initiation in a series of ten levels, the three highest of which were unattainable except by magi, who were thought to possess the secrets of supernatural wisdom and enjoy magically extended lives. Yeats remained an active member of the Golden Dawn for thirty-two years and achieved the coveted sixth grade of membership in 1914, the same year that his future wife, Georgiana Hyde-Lees, joined the society. Yeats’s 1899 poetry collection The Wind Among the Reeds featured several poems employing occult symbolism.

The Abbey Theatre. The turn of the century marked Yeats’s increased interest in theater, an interest influenced by his father, a famed artist and orator. In the summer of 1897, Yeats enjoyed his first stay at Coole Park, the County Galway estate of Lady Augusta Gregory. He, Lady Gregory, and her neighbor, Edward Martyn, devised plans for promoting an innovative, native Irish drama. In 1899 they staged the first of three annual productions in Dublin, including Yeats’s The Countess Kathleen. In 1902 they supported a company of amateur Irish actors in staging both George Russell’s Irish legend Deirdre and Yeats’s Cathleen ni Houlihan. The success of these productions led to the founding of the Irish National Theatre Society, of which Yeats became president. With a wealthy sponsor volunteering to pay for the renovation of Dublin’s Abbey Theatre as a permanent home for the company, the theater opened on December 27, 1904, and featured plays by the company’s three directors: Lady Gregory, John M. Synge (whose 1907 production The Playboy of the Western World would spark controversy with its savage comic depiction of Irish rural life), and Yeats, who opened that night with On Baile’s Strand, the first of his several plays featuring the heroic ancient Irish warrior Cuchulain.

The Easter Rising. While Yeats fulfilled his duties as president of the Abbey Theatre group for the first fifteen years of the twentieth century, his nationalistic fervor waned. Maud Gonne, with whom he had shared his Irish enthusiasms, had moved to Paris with her husband, exiled Irish revolutionary John MacBride, and the author was left without her important encouragement. His emotion was reawakened in 1916’s Easter Rising, an unsuccessful, six-day armed rebellion of Irish republicans against the British in Dublin. MacBride, who was now separated from Gonne, participated in the rebellion and was executed afterward. Yeats reacted by writing ‘‘Easter, 1916,’’ an eloquent expression of his feelings of shock and admiration. The Easter Rising contributed to Yeats’s eventual decision to reside in Ireland rather than England, and his marriage to Georgianna Hyde-Lees in 1917 further strengthened that resolve. Once married, Yeats traveled with his bride to Thoor Ballylee, a medieval stone tower where the couple periodically resided.

In the 1920s, Ireland was full of internal strife. In 1921 bitter controversies erupted within the new Irish Free State over the partition of Northern Ireland and over the wording of a formal oath of allegiance to the British Crown. These issues led to the Irish Civil War, which lasted from June 1922 to May 1923. Yeats emphatically sided with the new Irish government in this conflict. He accepted a six-year appointment to the senate of the Irish Free State in December 1922, a time when rebels were kidnapping government figures and burning their homes. In Dublin, where Yeats had assumed permanent residence in 1922, the government posted armed sentries at his door. As senator, Yeats considered himself a representative of order amid the new nation’s chaotic progress toward stability. He was now the ‘‘sixty-year-old smiling public man’’ of his poem ‘‘Among School Children,’’ which he wrote after touring an Irish elementary school. But he was also a world renowned artist of impressive stature; he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923.

Old Age and Last Poems. The poems and plays Yeats created during his senate term and beyond are, at once, local and general, personal and public, Irish and universal. The energy of the poems written in response to these disturbing times gave power to his collection The Tower, which is often considered his best single book. Another important element of these later poems is Yeats’s keen awareness of old age. His romantic poems from the late 1890s often mention gray hair and weariness, though those poems were written while he was still a young man. When Yeats was nearly sixty, his health began to fail, and he faced what he called “bodily decrepitude’’ that was real, not imaginary. Despite the author’s keen awareness of his physical decline, the last fifteen years of his life were marked by extraordinary vitality and appetite. He continued to write plays, including ‘‘The Words upon the Window Pane,’’ a full-length work about spiritualism and the eighteenth-century Irish writer Jonathan Swift. In 1929, as an expression of thankful joy after recovering from serious illness, he also wrote a series of brash, vigorous poems narrated by a fictitious old peasant woman, ‘‘Crazy Jane.’’ Yeats faced death with a courage that was founded partly on his vague hope for reincarnation and partly on his admiration for the bold heroism that he perceived in Ireland in both ancient times and the eighteenth century. He died, after a series of illnesses, in 1939, and after a quick burial in France, was exhumed and reburied in his beloved Sligo. His epitaph, one of the most famous of tombstone inscriptions, comes from his own poem ‘‘Under Ben Bulben’’: ‘‘Cast a cold eye / On life, on death. / Horseman, pass by!’’

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Yeats's famous contemporaries include:

Madame Blavatsky (1831-1891): A world-renowned psychic medium, Blavatsky founded the Theosophical Society.

Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory (1852-1932): Lady Gregory was one of the founders of the Abbey Theatre, as well as Yeats's lifelong benefactor.

John MacBride (1865-1916): This Irish Nationalist married Maud Gonne, the love of Yeats's life, and was executed for his part in the Easter Rebellion of 1916.

John Millington Synge (1871-1909): Synge was an Abbey Theatre playwright who wrote The Playboy of the Western World (1907).

James Joyce (1882-1941): A famous Irish novelist, Joyce is most known for the modern epic Ulysses (1922) and the autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916).

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Yeats's ideas and themes, while varied, were mired in his love for Ireland, and his imagery was often centered around Irish landscape and folklore. Here are some other works with significantly nationalistic themes.

Dr. Zhivago (1956), by Boris Pasternak. This torrid love story is set during the turbulent Russian Revolution of 1917.

One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Set in the fictional town of Macondo, this novel is an extended metaphor about Colombian and South American history.

The Journals of Susanna Moodie (1970), by Margaret Atwood. Chronicles the trials and tribulations of a woman living in the Canadian wilderness in the late nineteenth century.

Disgrace (1999), by J. M. Coetzee. The protagonist of this novel set in Cape Town must confront a number of difficult issues in post-apartheid South Africa.

Works in Literary Context

Yeats was, from first to last, a poet who tried to transform the concerns of his own life by embodying them in the universal language of his poems. His brilliant rhetorical accomplishments, strengthened by his considerable powers of rhythm and poetic phrase, have earned wide praise from readers and from fellow poets, including W. H. Auden (who praised Yeats as the savior of English lyric poetry), Stephen Spender, Theodore Roethke, and Philip Larkin. It is not likely that time will diminish his achievements.

Ireland’s Writer. In 1885 Yeats met John O’Leary, a famous patriot who had returned to Ireland after twenty years of imprisonment and exile for revolutionary activities. O’Leary had a keen enthusiasm for Irish books, music, and ballads, and he encouraged young writers to adopt Irish subjects. Yeats, who had preferred more romantic settings and themes, soon took O’Leary’s advice, producing many poems based on Irish legends, Irish folklore, and Irish ballads and songs. He explained in a note included in the 1908 volume Collected Works in Verse and Prose of William Butler Yeats-. ‘‘When I first wrote I went here and there for my subjects as my reading led me, and preferred to all other countries Arcadia and the India of romance, but presently I convinced myself... that I should never go for the scenery of a poem to any country but my own, and I think that I shall hold to that conviction to the end.’’ Indeed, Yeats turned almost exclusively to the folklore, culture, history, and landscape of Ireland for his inspiration.

Works in Critical Context

For many years, Yeats’s intent interest in subjects that others labeled archaic delayed his recognition among his peers. At the time of his death in 1939, Yeats’s views on poetry were regarded as eccentric by students and critics alike. This attitude held sway in spite of critical awareness of the beauty and technical proficiency of his verse. Yeats had long opposed the notion that literature should serve society. As a youthful critic he had refused to praise the poor lyrics of the ‘‘Young Ireland’’ poets merely because they were effective as nationalist propaganda.

In maturity, he found that despite his success, his continuing conviction that poetry should express the spiritual life of the individual estranged him from those who believed that a modern poet must take as his themes social alienation and the barrenness of materialist culture. As Kathleen Raine wrote of him: ‘‘Against a rising tide of realism, political verse and University wit, Yeats upheld the innocent and the beautiful, the traditional and the noble,’’ and in consequence of his disregard for the concerns of the modern world, was often misunderstood. As critics became disenchanted with modern poetic trends, Yeats’s romantic dedication to the laws of the imagination and art for art’s sake became more acceptable.

Indeed, critics today are less concerned with the validity of Yeats’s occult and visionary theories than with their symbolic value as expressions of timeless ideals.

The Winding Stair and Other Poems. The Winding Stair and Other Poems (1933) includes sixty-four poems in a wide range of form and tone. The volume opens with the beautiful romantic rhapsody ‘‘In Memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Con Markiewicz,’’ addressing the horse-riding Gore-Booth sisters of his Sligo youth, remembered as ‘‘Two girls in silk kimonos, both / Beautiful, one a gazelle,’’ but now ‘‘withered old and skeleton-gaunt’’ with time and political passion. The poem ends in an ecstasy of acceptance and defiance of tragic reality in which Yeats does not separate his own history from theirs.

The emblems of the tower and Sato's sword keep recurring in this volume. In the tiny poem ‘‘Symbols’’ the tower carries its usual connotations of withdrawal, contemplation, and arcane study, and the sword blade is violently active, ‘‘all-destroying.’’ Yeats is both the tower’s ‘‘blind hermit’’ and the ‘‘wandering fool’’ who carries the sword. But the tower is also the house of the marriage bed, and the phallic sword's housing is the feminine ‘‘gold-sewn silk’’ of the scabbard. So the final couplet couples the coupling of all the emblems: ‘‘Gold-sewn silk on the sword-blade / Beauty and fool together laid.’’

In ‘‘Blood and the Moon’’ Yeats abruptly alters the symbolic value of the tower, making it ‘‘my symbol’’ and emblematic of a self that is specifically Irish, involved in historical time and in the conflicting spiritual values that divide real personalities. ‘‘Quarrel in Old Age’’ of this volume describes Dublin offhandedly as ‘‘this blind bitter town,’’ and ‘‘Remorse for Intemperate Speech’’ puts in capsule form the compacted bitterness that Yeats had long seen as genetic in Irish character: ‘‘Great hatred, little room, / Maimed us from the start.’’ In ‘‘Blood and the Moon'' his scene is contemporary Ireland, against which he erects his roofless tower: ‘‘In mockery of a time / Half dead at the top.’’ Yeats’s verse swoops and soars with his mind: ‘‘I declare this tower is my symbol; I declare / This winding, gyring, spiring treadmill of a stair is my ancestral stair; / That Goldsmith and the Dean, Berkeley and Burke have travelled there.’’

“The Second Coming’’. Based in part on his ideas in A Vision, ‘‘The Second Coming’’ has resonance today. The poem moves with a confident mastery, but here the vision is sweeping and apocalyptic, the rhetoric formal, grand, full of power, the structure that of two stately violent blank-verse paragraphs. In it, Yeats dramatizes his cyclical theory of history: that whole civilizations rotate in a ‘‘gyre’’ of about two thousand years, undergoing birth, life, and death and preparing all the while for the life of its opposing successor. The critical period of the ‘‘interchange of tinctures,’’ when one era struggles to die and its ‘‘executioner’’ struggles to be born, will be violent and dreadful. Yeats's poem remembers war and revolution and inhabits an apocalyptic climate in which man has lost touch with God, with any center of order.

Essayist Joan Didion borrowed from the poem the title of her 1968 collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem and this is generally regarded as one of Yeats's most important and most widely anthologized poems.

Responses to Literature

1. Study Yeats’s ‘‘The Second Coming’’ and construct a version of his gyres for today. What sorts of events and people do you think might be caught in the intersecting cones? If Yeats were alive today, which political events do you think he would choose to include?

2. Read W. H. Auden’s ‘‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’’ and connect this eulogy to any five of Yeats’s poems. Do you think Yeats would have felt ‘‘honored'' by Auden's poem?

3. Read ‘‘Adam’s Curse,’’ ‘‘No Second Troy,’’ and ‘‘When You Are Old’’ and determine 1) why you think these poems could be about Maud Gonne specifically and 2) whether Yeats was truly in love with her or merely obsessed with the idea of her.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Alldritt, Keith. W. B. Yeats: The Man and the Milieu. New York: Clarkson Potter, 1997.

Allen, James Lovic. Yeats’s Epitaph: A Key to Symbolic Unity in His Life and Work. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1982.

Bloom, Harold. Yeats. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Brown, Terence. The Life of W. B. Yeats: A Critical Biography. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1999.

Chaudhry, Yug Mohit. Yeats, the Irish Literary Revival, and the Politics of Print. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2001.

Doggett, Rob. Deep-Rooted Things: Empire and Nation in the Poetry and Drama of William Butler Yeats. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2006.

Finneran, Richard J. ed., Critical Essays on W. B. Yeats. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1986.

Fletcher, Ian. W. B. Yeats and His Contemporaries. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987.

Hall, James, and Martin Steinmann, eds., The Permanence of Yeats. New York: Collier, 1961.

MacBride, Maud Gonne. A Servant of the Queen. Dublin, Ireland: Golden Eagle, 1950.

Marcus, Phillip L. Yeats and the Beginning of the Irish Renaissance. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1970.

Robinson, Lenox. Ireland’s Abbey Theatre: A History 1869-1951. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1951; Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press, 1968.

Vendler, Helen H. Yeats’s “Vision’’ and the Later Plays. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1963.