Calculus AB and Calculus BC

CHAPTER 9 Differential Equations

E. EXPONENTIAL GROWTH AND DECAY

We now apply the method of separation of variables to three classes of functions associated with different rates of change. In each of the three cases, we describe the rate of change of a quantity, write the differential equation that follows from the description, then solve—or, in some cases, just give the solution of—the d.e. We list several applications of each case, and present relevant problems involving some of the applications.

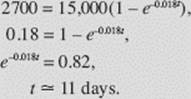

Case I: Exponential Growth

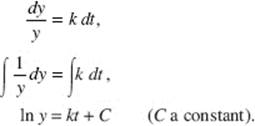

An interesting special differential equation with wide applications is defined by the following statement: “A positive quantity y increases (or decreases) at a rate that at any time t is proportional to the amount present.” It follows that the quantity y satisfies the d.e.

![]()

where k > 0 if y is increasing and k < 0 if y is decreasing.

From (1) it follows that

Then

![]()

If we are given an initial amount y, say y0 at time t = 0, then

y0 = c · ek · 0 = c · 1 = c,

and our law of exponential change

![]()

tells us that c is the initial amount of y (at time t = 0). If the quantity grows with time, then k > 0; if it decays (or diminishes, or decomposes), then k < 0. Equation (2) is often referred to as the law of exponential growth or decay.

The length of time required for a quantity that is decaying exponentially to be reduced by half is called its half-life.

EXAMPLE 12

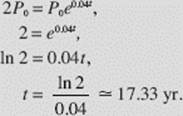

The population of a country is growing at a rate proportional to its population. If the growth rate per year is 4% of the current population, how long will it take for the population to double?

SOLUTION: If the population at time t is P, then we are given that ![]() Substituting in equation (2), we see that the solution is

Substituting in equation (2), we see that the solution is

P = P0 e0.04t,

where P0 is the initial population. We seek t when P = 2P0:

EXAMPLE 13

The bacteria in a certain culture increase continuously at a rate proportional to the number present.

(a) If the number triples in 6 hours, how many will there be in 12 hours?

(b) In how many hours will the original number quadruple?

SOLUTIONS: We let N be the number at time t and N0 the number initially. Then

![]()

hence, C = ln N0. The general solution is then N = N0 ekt, with k still to be determined.

Since N = 3N0 when t = 6, we see that 3N0 = N0 e6k and that ![]() ln 3. Thus

ln 3. Thus

N = N0 e(t ln 3)/6.

(a) When t = 12, N = N0 e2 ln 3 = N0 eln 32 = N0 eln 9 = 9N0.

(b) We let N = 4N0 in the centered equation above, and get

![]()

EXAMPLE 14

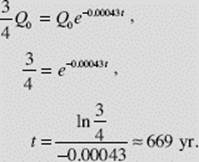

Radium-226 decays at a rate proportional to the quantity present. Its half-life is 1612 years. How long will it take for one quarter of a given quantity of radium-226 to decay?

SOLUTION: If Q(t) is the amount present at time t, then it satisfies the equation

![]()

where Q0 is the initial amount and k is the (negative) factor of proportionality. Since it is given that ![]() when t = 1612, equation (1) yields

when t = 1612, equation (1) yields

We now have

![]()

When one quarter of Q0 has decayed, three quarters of the initial amount remains. We use this fact in equation (2) to find t:

Applications of Exponential Growth

(1) A colony of bacteria may grow at a rate proportional to its size.

(2) Other populations, such as those of humans, rodents, or fruit flies, whose supply of food is unlimited may also grow at a rate proportional to the size of the population.

(3) Money invested at interest that is compounded continuously accumulates at a rate proportional to the amount present. The constant of proportionality is the interest rate.

(4) The demand for certain precious commodities (gas, oil, electricity, valuable metals) has been growing in recent decades at a rate proportional to the existing demand.

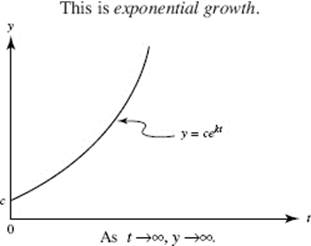

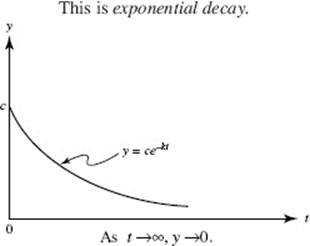

Each of the above quantities (population, amount, demand) is a function of the form cekt (with k > 0). (See Figure N9–7a.)

(5) Radioactive isotopes, such as uranium-235, strontium-90, iodine-131, and carbon-14, decay at a rate proportional to the amount still present.

(6) If P is the present value of a fixed sum of money A due t years from now, where the interest is compounded continuously, then P decreases at a rate proportional to the value of the investment.

(7) It is common for the concentration of a drug in the bloodstream to drop at a rate proportional to the existing concentration.

(8) As a beam of light passes through murky water or air, its intensity at any depth (or distance) decreases at a rate proportional to the intensity at that depth.

Each of the above four quantities (5 through 8) is a function of the form ce−kt (k > 0). (See Figure N9–7b.)

FIGURE N9–7a

FIGURE N9–7b

EXAMPLE 15

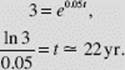

At a yearly rate of 5% compounded continuously, how long does it take (to the nearest year) for an investment to triple?

SOLUTION: If P dollars are invested for t yr at 5%, the amount will grow to A = Pe0.05t in t yr. We seek t when A = 3P:

EXAMPLE 16

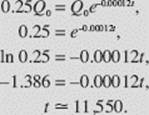

One important method of dating fossil remains is to determine what portion of the carbon content of a fossil is the radioactive isotope carbon-14. During life, any organism exchanges carbon with its environment. Upon death this circulation ceases, and the14 C in the organism then decays at a rate proportional to the amount present. The proportionality factor is 0.012% per year.

When did an animal die, if an archaeologist determines that only 25% of the original amount of14 C is still present in its fossil remains?

SOLUTION: The quantity Q of14 C present at time t satisfies the equation

![]()

with solution

Q(t) = Q0 e−0.00012t

(where Q0 is the original amount). We are asked to find t when Q(t) = 0.25Q0.

Rounding to the nearest 500 yr, we see that the animal died approximately 11,500yr ago.

EXAMPLE 17

In 1970 the world population was approximately 3.5 billion. Since then it has been growing at a rate proportional to the population, and the factor of proportionality has been 1.9% per year. At that rate, in how many years would there be one person per square foot of land? (The land area of Earth is approximately 200,000,000 mi2, or about 5.5 × 1015 ft2.)

SOLUTION: If P(t) is the population at time t, the problem tells us that P satisfies the equation ![]() Its solution is the exponential growth equation

Its solution is the exponential growth equation

P(t) = P0 e0.019t,

where P0 is the initial population. Letting t = 0 for 1970, we have

3.5 × 109 = P(0) = P0 e0 = P0.

Then

P(t) = (3.5 × 109)e0.019t.

The question is: for what t does P(t) equal 5.5 × 1015? We solve

![]()

Taking the logarithm of each side yields

![]()

where it seems reasonable to round off as we have. Thus, if the human population continued to grow at the present rate, there would be one person for every square foot of land in the year 2720.

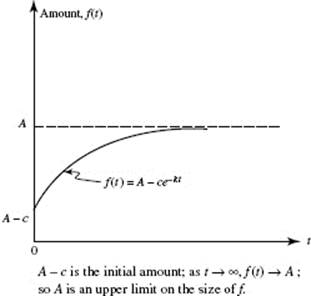

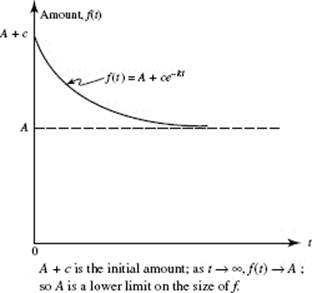

Case II: Restricted Growth

The rate of change of a quantity y = f (t) may be proportional, not to the amount present, but to a difference between that amount and a fixed constant. Two situations are to be distinguished: The rate of change is proportional to

|

(a) a fixed constant A minus the amount of the quantity present: |

(b) the amount of the quantity present minus a fixed constant A: |

|

|

f ′(t) = k[A − f (t)] |

f ′(t) = −k[f (t) − A] |

where (in both) f (t) is the amount at time t and k and A are both positive. We may conclude that

|

(a) f (t) is increasing (Fig. N9–8a): |

(b) f (t) is decreasing (Fig. N9–8b): |

|

|

f (t) = A − ce−kt |

f (t) = A+ ce−kt |

for some positive constant c.

FIGURE N9–8a

FIGURE N9–8b

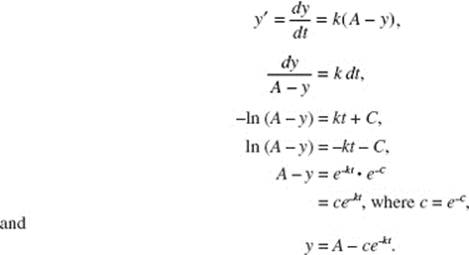

Here is how we solve the d.e. for Case II(a), where A − y > 0. If the quantity at time t is denoted by y and k is the positive constant of proportionality, then

Case II (b) can be solved similarly.

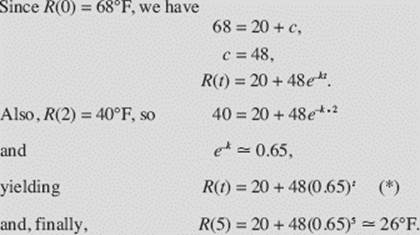

EXAMPLE 18

According to Newton’s law of cooling, a hot object cools at a rate proportional to the difference between its own temperature and that of its environment. If a roast at room temperature 68°F is put into a 20°F freezer, and if, after 2 hours, the temperature of the roast is 40°F:

(a) What is its temperature after 5 hours?

(b) How long will it take for the temperature of the roast to fall to 21°F?

SOLUTIONS: This is an example of Case II (b) (the temperature is decreasing toward the limiting temperature 20°F).

(a) If R(t) is the temperature of the roast at time t, then

![]()

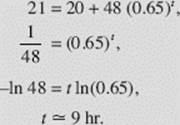

(b) Equation (*) in part (a) gives the roast’s temperature at time t. We must find t when R = 21:

EXAMPLE 19

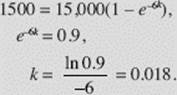

Advertisers generally assume that the rate at which people hear about a product is proportional to the number of people who have not yet heard about it. Suppose that the size of a community is 15,000, that to begin with no one has heard about a product, but that after 6 days 1500 people know about it. How long will it take for 2700 people to have heard of it?

SOLUTION: Let N(t) be the number of people aware of the product at time t. Then we are given that

N ′(t) = k[15,000 − N(t)],

which is Case IIa. The solution of this d.e. is

N(t) = 15,000 − ce−kt.

Since N(0) = 0, c = 15,000 and

N(t) = 15,000(1 − e−kt ).

Since 1500 people know of the product after 6 days, we have

We now seek t when N = 2700:

Applications of Restricted Growth

(1) Newton’s law of heating says that a cold object warms up at a rate proportional to the difference between its temperature and that of its environment. If you put a roast at 68°F into an oven of 400°F, then the temperature at time t is R(t) = 400 − 332e−kt.

(2) Because of air friction, the velocity of a falling object approaches a limiting value L (rather than increasing without bound). The acceleration (rate of change of velocity) is proportional to the difference between the limiting velocity and the object’s velocity. If initial velocity is zero, then at time t the object’s velocity V(t) = L(1 − e−kt).

(3) If a tire has a small leak, then the air pressure inside drops at a rate proportional to the difference between the inside pressure and the fixed outside pressure O. At time t the inside pressure P(t) = O + ce−kt.

BC ONLY

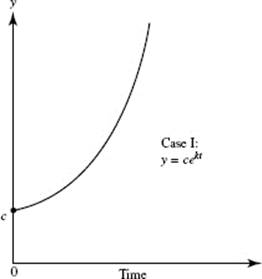

Case III: Logistic Growth

The rate of change of a quantity (for example, a population) may be proportional both to the amount (size) of the quantity and to the difference between a fixed constant A and its amount (size). If y = f(t) is the amount, then

![]()

where k and A are both positive. Equation (1) is called the logistic differential equation; it is used to model logistic growth.

The solution of the d.e. (1) is

![]()

for some positive constant c.

In most applications, c > 1. In these cases, the initial amount A/(1 + c) is less than A/2. In all applications, since the exponent of e in the expression for f (t) is negative for all positive t, therefore, as t → ∞,

(1) ce−Akt → 0;

(2) the denominator of f (t) → 1;

(3) f (t) → A.

Thus, A is an upper limit of f in this growth model. When applied to populations, A is called the carrying capacity or the maximum sustainable population.

Shortly we will solve specific examples of the logistic d.e. (1), instead of obtaining the general solution (2), since the latter is algebraically rather messy. (It is somewhat less complicated to verify that y ′ in (1) can be obtained by taking the derivative of (2).)

Unrestricted Versus Restricted Growth

FIGURE N9–9a

FIGURE N9–9b

BC ONLY

In Figures N9–9a and N9–9b we see the graphs of the growth functions of Cases I and III. The growth function of Case I is known as the unrestricted (or uninhibited or unchecked) model. It is not a very realistic one for most populations. It is clear, for example, that human populations cannot continue endlessly to grow exponentially. Not only is Earth’s land area fixed, but also there are limited supplies of food, energy, and other natural resources. The growth function in Case III allows for such factors, which serve to check growth. It is therefore referred to as the restricted(or inhibited) model.

The two graphs are quite similar close to 0. This similarity implies that logistic growth is exponential at the start—a reasonable conclusion, since populations are small at the outset.

The S-shaped curve in Case III is often called a logistic curve. It shows that the rate of growth y ′:

(1) increases slowly for a while; i.e., y ″ > 0;

(2) attains a maximum when y = A/2, at half the upper limit to growth;

(3) then decreases (y ″ < 0), approaching 0 as y approaches its upper limit.

It is not difficult to verify these statements.

Applications of Logistic Growth

(1) Some diseases spread through a (finite) population P at a rate proportional to the number of people, N(t), infected by time t and the number, P − N(t), not yet infected. Thus N ′(t) = kN(P − N) and, for some positive c and k,

![]()

(2) A rumor (or fad or new religious cult) often spreads through a population P according to the formula in (1), where N(t) is the number of people who have heard the rumor (acquired the fad, converted to the cult), and P − N(t) is the number who have not.

(3) Bacteria in a culture on a Petri dish grow at a rate proportional to the product of the existing population and the difference between the maximum sustainable population and the existing population. (Replace bacteria on a Petri dish by fish in a small lake, ants confined to a small receptacle, fruit flies supplied with only a limited amount of food, yeast cells, and so on.)

BC ONLY

(4) Advertisers sometimes assume that sales of a particular product depend on the number of TV commercials for the product and that the rate of increase in sales is proportional both to the existing sales and to the additional sales conjectured as possible.

(5) In an autocatalytic reaction a substance changes into a new one at a rate proportional to the product of the amount of the new substance present and the amount of the original substance still unchanged.

EXAMPLE 20

Because of limited food and space, a squirrel population cannot exceed 1000. It grows at a rate proportional both to the existing population and to the attainable additional population. If there were 100 squirrels 2 years ago, and 1 year ago the population was 400, about how many squirrels are there now?

SOLUTION: Let P be the squirrel population at time t. It is given that

![]()

with P(0) = 100 and P(1) = 400. We seek P(2).

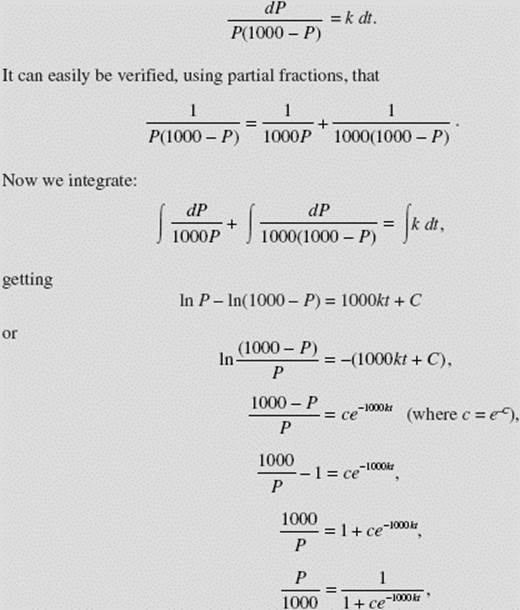

We will find the general solution for the given d.e. (3) by separating the variables:

and, finally (!),

![]()

Please note that this is precisely the solution “advertised” in equation (2), with A equal to 1000.

Now, using our initial condition P(0) = 100 in (4), we get

![]()

Using P(1) = 400, we get

Then the particular solution is

![]()

and P(2) ![]() 800 squirrels.

800 squirrels.

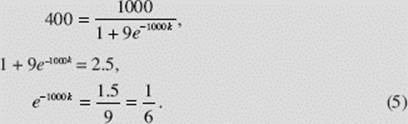

FIGURE N9–10

Figure N9–10 shows the slope field for equation (3), with k = 0.00179, which was obtained by solving equation (5) above. Note that the slopes are the same along any horizontal line, and that they are close to zero initially, reach a maximum at P = 500, then diminish again as Papproaches its limiting value, 1000. We have superimposed the solution curve for P(t) that we obtained in (6) above.

BC ONLY

EXAMPLE 21

Suppose a flu-like virus is spreading through a population of 50,000 at a rate proportional both to the number of people already infected and to the number still uninfected. If 100 people were infected yesterday and 130 are infected today:

(a) write an expression for the number of people N(t) infected after t days;

(b) determine how many will be infected a week from today;

(c) indicate when the virus will be speading the fastest.

SOLUTIONS:

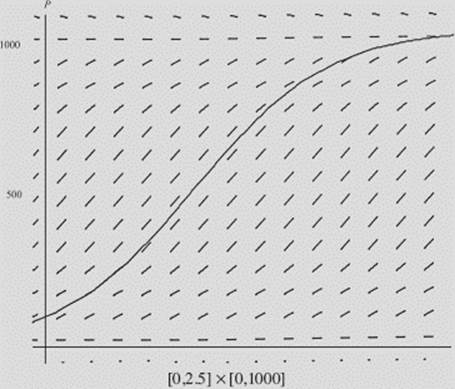

(a) We are told that N ′(t) = k · N · (50,000 −N), that N(0) = 100, and that N(1) = 130. The d.e. describing logistic growth leads to

![]()

From N(0) = 100, we get

![]()

which yields c = 499. From N(1) = 130, we get

Then

![]()

(b) We must find N(8). Since t = 0 represents yesterday:

![]()

(c) The virus spreads fastest when 50,000/2 = 25,000 people have been infected.

Chapter Summary and Caution

In this chapter, we have considered some simple differential equations and ways to solve them. Our methods have been graphical, numerical, and analytical. Equations that we have solved analytically—by antidifferentiation—have been separable.

It is important to realize that, given a first-order differential equation of the type ![]() it is the exception, rather than the rule, to be able to find the general solution by analytical methods. Indeed, a great many practical applications lead to d.e.’s for which no explicit algebraic solution exists.

it is the exception, rather than the rule, to be able to find the general solution by analytical methods. Indeed, a great many practical applications lead to d.e.’s for which no explicit algebraic solution exists.