Mathematics and the Real World: The Remarkable Role of Evolution in the Making of Mathematics (2014)

CHAPTER II. MATHEMATICS AND THE GREEKS’ VIEW OF THE WORLD

12. MODELS OF THE HEAVENLY BODIES

The Greeks inherited a wealth of astronomic measurements from the Babylonians and the Egyptians. These included information on the movement of the planets, the lengths of a year and a month, the cyclicality of the relation between the solar year and the lunar year, the effects of all these on agriculture, and so on. The Greeks made great efforts over many years to improve the measurements and to add new ones, and they developed the ability to forecast celestial events with the greatest precision. For example, whereas the Egyptians gave the length of the year as 365 days, the Greeks of the fifth century BCE determined it as 365 days, 6 hours, 18 minutes and 56 seconds, which is a deviation of just half an hour from the correct figure. In 130 BCE the Greeks achieved greater precision and set the length of the year at 365 days, 5 hours, 55 minutes and 12 seconds, a deviation of only six minutes and twenty-six seconds from the true figure. These measurements were achieved following the development of advanced mathematical methods of calculation and measurement. We will not expand on those methods here, as our focus is on how mathematics explains nature.

We will now review the conceptual and mathematical contributions made by the Greeks to the development of a model of the heavenly bodies, both in the classical period and thereafter. This development reached its peak in Ptolemy's (Claudius Ptolemaeus's) model. It should be mentioned again that there is no direct written evidence from the classical period, and the information available to us relating to that period is derived from remarks in much later writings, writings that reflected the authors’ points of view. Therefore, we should not place too much credence on the precision or reliability of those descriptions. We will not be able to set out here the detailed development of the Greeks’ picture of the heavenly bodies, but we will concentrate mainly on the conceptual development of the models.

The part of mathematics that the Greeks used to describe the movement of the heavenly bodies was geometry. From our standpoint today, two thousand five hundred years later, this role of geometry seems obvious. The heavenly bodies, including the planets, the Sun, and the Moon, move in space, and it seems natural to find out what geometric paths describe their movement. That, however, is an incorrect conclusion. The early Greeks had no knowledge of a physical space in which the heavenly bodies existed. The stars were spots of light in the heavens, and it was unclear what the Sun and the Moon were. Moreover, the distance of those objects, if indeed they were objects, from Earth was not known. At that level of understanding, to enlist geometry to describe the movement of the heavenly bodies was a bold pioneering step and by no means obvious. Geometry was known and well developed as a mathematical tool for describing earthly objects and as a useful device in measuring and building. The Greeks used the known earthly mathematics as a basis for cosmological research.

Plato advocated a view based on the Pythagorean outlook, according to which the heavenly bodies moved on the surfaces of spheres. Consistent with appearances, Plato claimed that the planets, the Sun, and the Moon circled the Earth, and those circles were all on one plane. He realized that this description did not cover the irregular movement of the planets and the Moon relative to the fixed stars in the sky. Specifically, according to his description, eclipses of the Moon should have occurred about once a month, but they did not. It was Plato who set the objective of improving the mathematical description of the movement of the heavenly bodies.

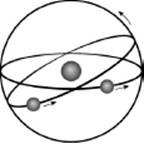

The challenge was taken up by Eudoxus, Plato's colleague in the Academy of Athens, whose contribution to mathematics was discussed in section 7. Eudoxus accepted Plato's assumptions that the Earth was static in its place and the heavenly bodies moved in circular orbits around it. Eudoxus proposed two significant innovations. First, he allowed the circles defining the movement of the planets, the Sun, and the Moon to be at an angle to each other, that is, on different planes. Second, he allowed each of the heavenly bodies to revolve on more than one sphere and the spheres to move in different directions and at different speeds.

The flexibility afforded by these new ideas enabled Eudoxus, by means of sophisticated use of three-dimensional geometry, to define the number of spheres on which each planet was situated, its speed, and its direction so that most of the observations that were inconsistent with the previous model could now be explained. The movement of two planets, Venus and Mercury, still did not fit the model satisfactorily. It should be pointed out that the Greek astronomers did not stop at the geometric description of the paths of the heavenly bodies but struggled to calculate their orbits and to show how the models they proposed were consistent with the various observations and measurements they performed on the movement of the stars. The calculations required great mathematical ability combined with a deep understanding of geometry.

Heraclides of Pontus (in today's Turkey) proposed two far-reaching amendments to Eudoxus's model. Heraclides (388–310 BCE), an important philosopher in his own right, studied under Plato at the Academy of Athens and occasionally stood in for him as head of the academy when Plato was on his frequent journeys. The two amendments were as follows.

First, he claimed that Venus and Mercury did not orbit the Earth but revolved around the Sun, while the Sun itself orbited the Earth. This claim may be seen as the source of the epicycles model, a model attributed to Appolonius, whom we will meet further on. The second amendment was that the firmament and the planets do not revolve around the Earth at all, but the fact that the Earth revolves on its own axis makes us think that they do. Heraclides proposed the first amendment based on the fact that Mercury sometimes disappears behind the Sun. The assumption that Venus and Mercury orbited the Sun was more consistent with the observed movements of the planets than Eudoxus's model. Heraclides's argument in favor of the Earth revolving around its own axis was purely aesthetic. At that time, the size of the universe, including the firmament, relative to the size of the Earth, was already appreciated. It does not seem fitting, said Heraclides, that such a large sky should revolve around such a small body as the Earth, and he added that the Earth turning on its axis would explain equally well what we see. This argument based on aesthetics will recur again and again throughout all the years of the development of physical science. It is also consistent with the “self-evident” assumption, which Heraclides accepted, that the stars move in perfect circles.

We should mention that historians do not agree on the question of whether Heraclides himself actually proposed these amendments because there is no clear reference in Greek sources stating that he held those views. The attribution to Heraclides derives from the writings of Copernicus in the sixteenth century CE (see section 15). Nonetheless, whether he did or not, those ideas and others we shall refer to later on were heard in classical Greece but were not accepted by those who determined the mainstream in Greek science.