Hacking Assessment: 10 Ways to Go Gradeless in a Traditional Grades School (2015)

HACK 1. SHIFT THE GRADES MINDSET

Start a no-grades classroom

The more we want our children to be (1) lifelong learners, genuinely excited about words and numbers and ideas, (2) avoid sticking with what’s easy and safe, and (3) become sophisticated thinkers, the more we should do everything possible to help them forget about grades.

— ALFIE KOHN, AMERICAN AUTHOR/LECTURER

THE PROBLEM: THE TRADITIONAL GRADING SYSTEM

TRADITIONAL GRADING HAS been ingrained in American educational culture for more than a century. Because of the culture of grades that has emerged, we have lost sight of what is important in school: the learning. Too many students, parents, and educators focus excessively on labeling learning with numbers; they are willing to let that number or letter represent almost anything that can happen. Here are a few issues with traditional grading that must be hacked:

· Grades misrepresent what students know and can do because they oversimplify student achievement and categorize children into narrow boxes that stifle growth.

· Grades generate a competitive learning culture that de-emphasizes progress and pits students against each other. Since grades are often inflated with non-learning elements, they rarely demonstrate authentic or meaningful progress. Students then use the score they got on a test or a report card as an opportunity to claim they did better or know more than others, unaware that it is not an accurate representation of their ability. This is not an atmosphere that fosters risk taking.

· The language associated with grading often has a negative connotation that shuts the learning process down. Consider how it feels when a teacher tells a student he or she is wrong and draws a big “X” next to a child’s work—that doesn’t stimulate learning. Later in this chapter we will explore other language that can be adjusted to communicate effectively and positively.

THE HACK: SHIFT THE MINDSET AND THROW OUT GRADES

It’s time to change the way we communicate about learning, and the most important step is to make sure all stakeholders understand why the shift is necessary. We need to help everyone involved, particularly students, understand that grades don’t represent the depth of their understanding, that in fact grades are a short-sighted way to explore or to communicate about learning. Introducing a growth mindset, as Carol Dweck discusses in her book Mindset, is essential so students can evolve into successful learners—learners who are not quick to define themselves by letters or symbols that inadequately represent their learning.

Students must understand the various methods of feedback that their teacher and peers will provide and how to parlay that feedback into future growth.

Mindsets determine how we perceive the learning process. We must inspire students to focus on a growth mindset that allows for change and movement, rather than a fixed mindset that has the potential to stifle growth. When students earn C grades, they have a tendency to define themselves as “C students,” often becoming stuck with this label. If we remove the label, we encourage students to see themselves simply as learners.

The shift to a growth mindset demands a corresponding shift in language to discuss the learning and assessing processes. Teachers must emphasize that there are multiple paths to learning and no one way is better than another. When students ask about grades, challenge them to think about learning. When we give students feedback, we aren’t judging them; we are encouraging them to improve. This shift is an active one and will require vigilance on the part of the teacher and the learner.

WHAT YOU CAN DO TOMORROW

Transitioning away from traditional grades is a serious challenge, but there are several ways to ease the tension. Consider the following next steps:

· Talk about going gradeless. This discussion is essential: How you present it to students is going to determine how well they respond to the idea of eliminating grades. Begin by asking students what they think learning looks like. If they answer, “Doing all our work and getting A’s,” push back by asking more questions: “What do you get from doing all the work?” “What does it mean to get an A?”

Although a strong work ethic is a valuable attribute that we want to instill in students, it doesn’t define learning. You may ask them, “How many of you are afraid to fail?” If any raise their hands, ask, “What does failure mean?” It is essential that we develop a learning space where failure is positive, as it is a catalyst for growth and change. Students need to recognize that taking a risk and not succeeding does not mean they are failing: It means they need to try another way.

After posing the initial questions, break the class up into smaller groups to discuss the ideas that arose. See where the separate conversations take them and then bring them back to the whole class. Let students ask the questions. After all voices have been heard, end class with the opportunity to write about what they learned. What fears do they have about the upcoming year? How best can you help them transcend those fears? This will be their first reflection. While they write, so should you to show the value of the act and to model what will become a common practice.

If time permits, ask volunteers to read their reflections. Then share yours. Make a space in the classroom to post reflections as a reminder throughout the year. Let this be the beginning of a very important discussion that will not end in one day, but will continue all year long.

· Talk about mastery learning. Initially, students may be able to wrap their brains around the idea, but how this new process actually looks will feel like a mystery. Dispel the uncertainty by providing concrete examples of mastery learning. Discuss what it was like when they learned to ride a bike. The first time they tried, they may have failed; they may have fallen off the bike many times, but they kept getting up and trying again. Some may have started with training wheels, which is comparable to approaching proficiency; they could do it with help. Once they could ride without training wheels or help, they had reached proficiency. After they had been riding awhile and could go on rides for long distances or could ride different bikes, they had achieved mastery. You can then take this pattern and apply it to something students are learning.

A BLUEPRINT FOR FULL IMPLEMENTATION

Step 1: Continue the dialogue throughout the year.

Just because you had the conversation once doesn’t mean it’s over. Expect to have ongoing discussions about this concept all year long. Try not to get frustrated or exasperated when students need more time to take it in. They will continue to ask what they “got” on something and it will be your job to redirect the conversation—take the opportunity to remind them that learning has no grades. Instead ask them, “What did you learn from that assignment? What could you do now that you couldn’t do before? How do you know?” Students will come to expect the redirection until they have internalized the shift.

Step 2: Routinely review and clarify the standards of learning.

Make sure students understand class learning expectations (not rules) and standards. Have students translate expectations and standards into student-friendly language and internalize them; then, ask each student to determine his or her level of proficiency based on mastery of the standards. Since standards are often written in a language students don’t readily understand, it will take time to build a vocabulary and understanding of learning and each subject will require a specific jargon.

One way to help students know what they don’t know is by asking them to apply skills and knowledge to new situations without help. When they have reached mastery level, they can take what they know from one place and apply it appropriately to another without prompting, creating and synthesizing new ideas. Encourage students to generate and track short-term and long-term goals. Remind them that they are in control of their learning. In the spirit of effective differentiation, each child may be working on different outcomes within a unit at different times. Allowing them to determine their pace and skill will support future buy-in.

Step 3: Create and share feedback models regularly.

Exemplars will be your friend throughout the year, but even the best samples of last year’s work will need to be updated. (See the example at the end of this hack.) Students must understand the various methods of feedback that their teacher and peers will provide and how to parlay that feedback into future growth. For example, they will have opportunities to receive written feedback on work, to engage in short conversations during group projects, or to have one-on-one discussions that include specific strategies about different aspects of their learning. They will also be providing feedback to you about what works best for them.

Step 4: Change the vocabulary associated with learning.

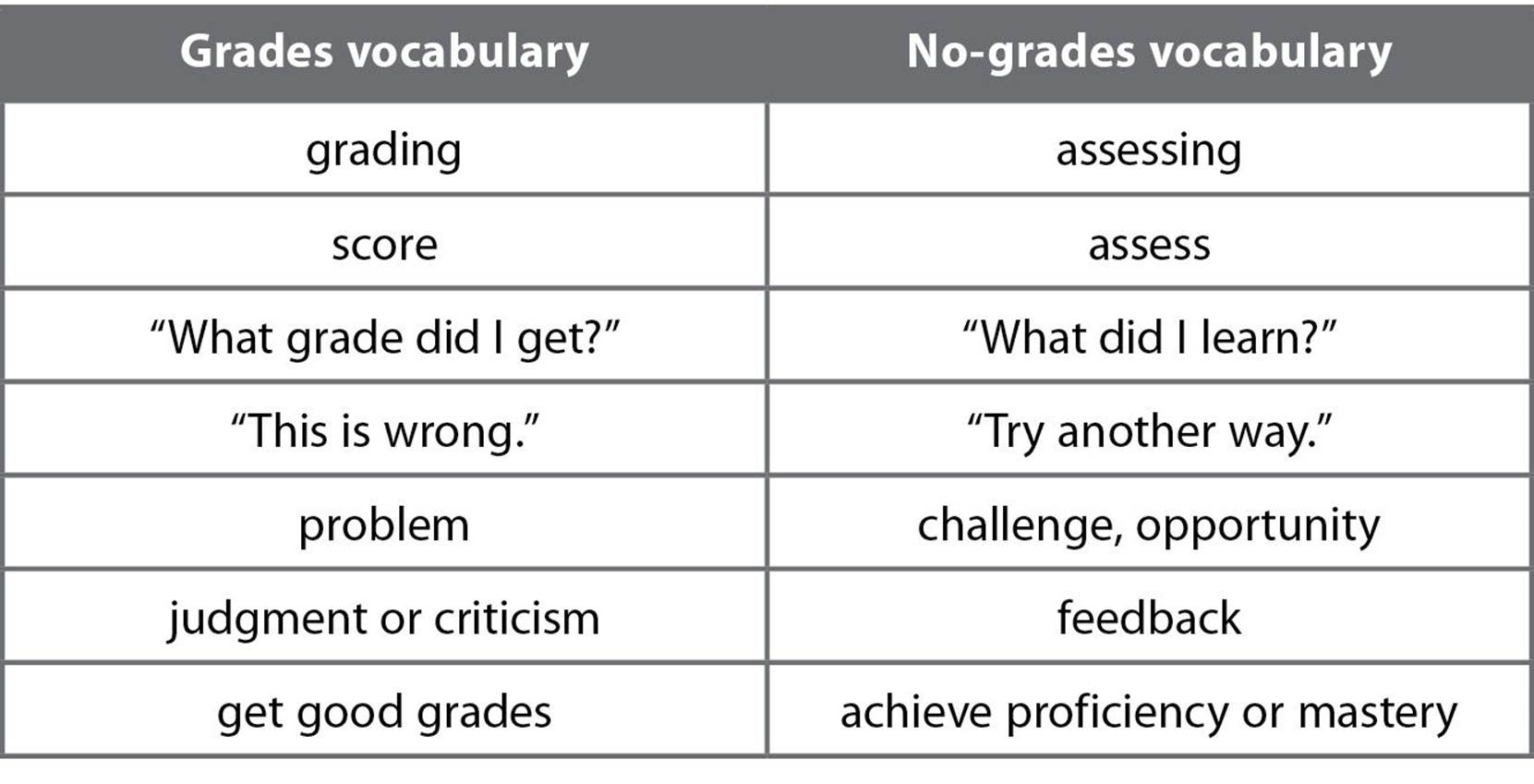

Traditional grading language is passive and is often negative, so we can shift the way we talk about assessment. Instead of using the words “grade” or “grading,” use “assessment” or “assessing.” We must be conscious of our diction, as our words characterize our thinking and communicate attitude: One simple word change can affect the connotation drastically.

OVERCOMING PUSHBACK

Some students may not like giving up grades because they have defined themselves in reference to these numbers and letters their whole lives. The more academically inclined the student is, the more reluctant he or she may be to relinquish the numbers and letters that make him or her feel smart. The parents of such a student will also likely make the shift more challenging (we’ll get to this in Hack 2).

Students and parents won’t understand this shift; they are used to grades. Let’s face it, this system is the only one they know and it’s validated by the fact that parents understand it and have instilled in their children that getting good grades is equal to success. Of course they do really want their kids to learn and generally will agree that learning is more important than the grade, so you will need to be patient. The best way to overcome this fixed mindset is to continue to have conversations and share the reasons you’ve eliminated grades and the value of assessment based on narrative feedback and self-evaluation.

Be strong. The system won’t change overnight; it will take time and many people making the conscious shift together. If you can get the whole school on board, that will greatly increase the likelihood of success with parents and students.

The unknown is very scary and therefore it won’t work. Many people will say that they don’t understand and are uncomfortable with the idea of doing something unknown, particularly if you are switching the system students are using toward the end of their secondary experience. They will worry about transcripts and report cards and college applications. You must reiterate that ultimately they will have all of those things—it’s just that their evaluation will involve a new process that encourages their involvement and requires them to take charge of their own learning. Remind them, console them, and help them understand that change is challenging, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t worthwhile. Don’t be afraid to hold their hands until you gain their trust. There will be times when the need for a whole class discussion will take priority over scheduled plans or when students need a one-on-one chat, so be flexible and patient.

Why change a system that isn’t broken? Some folks won’t like this idea, simply because they adhere to the status quo: “This is the way we’ve always done it and it isn’t broken!” Counter this argument with history: In the industrial era, schools were intended to train good workers, so students went to schools that prepared them to enter the work force. This model of education valued obedience, conformity, and rote learning. From there you can discuss how much the world has changed in the last hundred years and generate a list of ways that a 19th-century system doesn’t prepare kids for the creativity and critical thinking required of the 21st century.

THE HACK IN ACTION

At the beginning of my AP Literature and Composition class, I sent a letter home to parents explaining this essential shift in philosophy and practice about communicating learning. It didn’t seem like many of them read it, as no one sent me any confirmation. Most likely, parents cast it off with the other “unimportant” notices that go home senior year, but I wasn’t discouraged: My mind was made up.

“How am I going to know that I’m doing well if you don’t give us grades?” This question was on repeat for quite some time, but I assured students that we would be working on that together, first by making sure that the standards and expectations were clear, then by examining examples of mastery work and using frequent feedback.

For example, the first unit of the year was an exploration of poetry that focused on getting students to consider how a poem functions rather than what it means. Students were tasked with creating a tutorial about a particular poetic device or structure to be shared with their classmates. The assignment required students to research a poetic device, find examples of the device in poems, and then determine the best way to teach the material so their audience would learn it. They had two weeks in class to research and produce the tutorial; at the same time, we were doing whole class mini-lessons on the best way to accomplish these tasks.

Once students selected their groups, I met with each group to hear their ideas. I helped them to ensure that they stayed on target and presented accurate information. This feedback was intended to troubleshoot with them, not to provide answers, so I bounced questions and ideas off them, pointing them in the right direction. Part of the project’s purpose was for students to discover knowledge on their own.

While they worked, I was not only discussing progress, but was also observing group dynamics to see that all students were contributing. It’s important that each student receives individual feedback—the days of providing one group grade are over. I used to do it, but have changed my practice since reading Susan M. Brookhart’s book Grading and Group Work, which convinced me to assess students’ work individually.

Once students completed the project, we did a gallery walk: All of the projects were set up around the room on computers, and small groups moved around the room viewing the projects, taking notes, and tweeting questions and comments. They reviewed each group’s tutorial and provided feedback based on the standards using a Google form. Every student was required to submit a reflection and self-evaluation about what he or she learned as compared against the standards so that we could discuss growth. Students reflected on what they had hoped to get out of the assignment and then shared what they had learned.

After this process, some students continued to ask what they “got” or what I thought of their assignments, but I steadfastly replied, “It doesn’t really matter what I thought, so much as it matters what you learned. What did you learn from this learning experience?” At the beginning of the year, I frequently had to redirect students in this way. The true test of the system’s efficacy, however, was when it came time for them to write their first poetry analysis paper, a two- to three-page unresearched paper that asked them to apply the skills they had learned from the tutorials.

It wasn’t until after they wrote the paper that they began to recognize how much they had learned. In their reflections, I saw responses like, “I was able to use what we did in our group tutorial to help make sense of my poem, and that met this standard.” When students discussed their learning in an articulate and meaningful way, I knew they were starting to understand the value of the procedures we were using.

Eventually students told me that not worrying about grades made them more excited and eager to try things. Although they didn’t realize it yet, they had been like this when they were younger, before they were afraid of being wrong. By the end of the year, they saw the connection and recognized that the shift away from grades was worth the time and effort.

The success of the shift away from grades will come only from a full commitment to helping each child learn without labels. Although challenges will present themselves, both internally and externally, we must embrace the fact that growth is possible in everyone and it shouldn’t be tracked with scores: Those numbers and letters impede progress and stifle potential. Consider your own impact in the classroom. What do you do to model this mindset and what can you change personally to generate a more inclusive community in your space?

by STARR SACKSTEIN