Barron's AP Psychology, 7th Edition (2016)

Chapter 14. Social Psychology

KEY TERMS

Attitude

Mere exposure effect

Central versus peripheral route to persuasion

Cognitive dissonance

Foot-in-the-door

Door-in-the-face

Norms of reciprocity

Attribution theory

Self-fulfilling prophecy

Fundamental attribution error

Collectivist versus individualistic cultures

False-consensus effect

Self-serving bias

Just-world bias

Stereotype

Prejudice

Ethnocentrism

Discrimination

Out-group homogeneity

In-group bias

Superordinate goals

Frustration-aggression hypothesis

Bystander effect

Diffusion of responsibility

Pluralistic ignorance

Attraction research

Social facilitation

Social impairment

Conformity

Obedience

Group norms

Social loafing

Group polarization

Groupthink

Deindividuation

KEY PEOPLE

Richard LaPiere

Leon Festinger

James Carlsmith

Harold Kelley

Robert Rosenthal

Lenore Jacobson

Muzafer Sherif

John Darley

Bibb Latane

Solomon Asch

Stanley Milgram

Irving Janis

Phillip Zimbardo

OVERVIEW

Social psychology is a broad field devoted to studying the way that people relate to others. Our discussion will focus on the development and expression of attitudes, people’s attributions about their own behavior and that of others, the reasons why people engage in both antisocial and prosocial behavior, and how the presence and actions of others influence the way people behave.

A major influence on the first two areas we will discuss, attitude formation and attribution theory, is social cognition. This field applies many of the concepts you learned about in the field of cognition, such as memory and biases, to help explain how people think about themselves and others. The basic idea behind social cognition is that, as people go through their daily lives, they act like scientists, constantly gathering data and making predictions about what will happen next so that they can act accordingly.

ATTITUDE FORMATION AND CHANGE

One main focus of social psychology is attitude formation and change. An attitude is a set of beliefs and feelings. We have attitudes about many different aspects of our environment such as groups of people, particular events, and places. Attitudes are evaluative, meaning that our feelings toward such things are necessarily positive or negative.

A great deal of research focuses on ways to affect people’s attitudes. In fact, the entire field of advertising is devoted to just this purpose. How can people be encouraged to develop a favorable attitude toward a particular brand of potato chips? Having been the target audience for many such attempts, you are no doubt familiar with a plethora of strategies used to promote favorable opinions toward a product.

The mere exposure effect states that the more one is exposed to something, the more one will come to like it. Therefore, in the world of advertising, more is better. When you walk into the supermarket, you will be more likely to buy the brand of potato chips you have seen advertised thousands of times rather than one that you have never heard of before.

Persuasive messages can be processed through the central route or the peripheral route. The central route to persuasion involves deeply processing the content of the message; what about this potato chip is so much better than all the others? The peripheral route, on the other hand, involves other aspects of the message including the characteristics of the person imparting the message (the communicator).

Certain characteristics of the communicator, have been found to influence the effectiveness of a message. Attractive people, famous people, and experts are among the most persuasive communicators. As a result, professional athletes and movie stars often have second careers making commercials. Certain characteristics of the audience also affect how effective a message will be. Some research suggests that more educated people are less likely to be persuaded by advertisements. Finally, the way the message is presented can also influence how persuasive it is. Research has found that when dealing with a relatively uninformed audience, presenting a one-sided message is best. However, when attempting to influence a more sophisticated audience, a communication that acknowledges and then refutes opposing arguments will be more effective. Some research suggests that messages that arouse fear are effective. However, too much fear can cause people to react negatively to the message itself.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIOR

Although you might think that knowing people’s attitudes would tell you a great deal about their behavior, research has found that the relationship between attitudes and behaviors is far from perfect. In 1934, Richard LaPiereconducted an early study that illustrated this difference. In the United States in the 1930s, prejudice and discrimination against Asians was pervasive. LaPiere traveled throughout the West Coast visiting many hotels and restaurants with an Asian couple to see how they would be treated. On only one occasion were they treated poorly due to their race. A short time later, LaPiere contacted all of the establishments they had visited and asked about their attitudes toward Asian patrons. Over 90 percent of the respondents said that they would not serve Asians. This finding illustrates that attitudes do not perfectly predict behaviors.

TIP

Attitudes do not perfectly predict behaviors. What people say they would do and what they actually would do often differ.

Sometimes if you can change people’s behavior, you can change their attitudes. Cognitive dissonance theory is based on the idea that people are motivated to have consistent attitudes and behaviors. When they do not, they experience unpleasant mental tension or dissonance. For example, suppose Amira thinks that studying is only for geeks. If she then studies for 10 hours for her chemistry test, she will experience cognitive dissonance. Since she cannot, at this point, alter her behavior (she has already studied for 10 hours), the only way to reduce this dissonance is to change her attitude and decide that studying does not necessarily make someone a geek. Note that this change in attitude happens without conscious awareness.

Leon Festinger and James Carlsmith conducted the classic experiment about cognitive dissonance in the late 1950s. Their participants performed a boring task and were then asked to lie and tell the next subject (actually a confederate1 of the experimenter) that they had enjoyed the task. In one condition, subjects were paid $1 to lie, and in the other condition they were paid $20. Afterward, the participants’ attitudes toward the task were measured. Contrary to what reinforcement theory would predict, those subjects who had been paid $1 were found to have significantly more positive attitudes toward the experiment than those who were paid $20. According to Festinger and Carlsmith, having already said that the boring task was interesting, the subjects were experiencing dissonance. However, those subjects who had been paid $20 experienced relatively little dissonance; they had lied because they had been paid $20. On the other hand, those subjects who were paid only $1 lacked sufficient external motivation to lie. Therefore, to reduce the dissonance, they changed their attitudes and said that they actually did enjoy the experiment.

COMPLIANCE STRATEGIES

Often people use certain strategies to get others to comply with their wishes. Such compliance strategies have also been the focus of much psychological research. Suppose you need to borrow $20 from a friend. Would you be better off asking him or her for $20 right away, asking the friend first for $5 and then following up this request with another for the additional $15, or asking him or her for $100 and, after the friend refuses, asking for $20? The foot-in-the-door phenomenon suggests that if you can get people to agree to a small request, they will become more likely to agree to a follow-up request that is larger. Thus, once your friend agrees to lend you $5, he or she becomes more likely to lend you the additional funds. After all, the friend is clearly willing to lend you money. The door-in-the-face strategy argues that after people refuse a large request, they will look more favorably upon a follow-up request that seems, in comparison, much more reasonable. After flat-out refusing to lend you $100, your friend might feel bad. The least he or she could do is lend you $20.

Another common strategy involves using norms of reciprocity. People tend to think that when someone does something nice for them, they ought to do something nice in return. Norms of reciprocity is at work when you feel compelled to send money to the charity that sent you free return address labels or when you cast your vote in the student election for the candidate that handed out those delicious chocolate chip cookies.

ATTRIBUTION THEORY

Attribution theory is another area of study within the field of social cognition. Attribution theory tries to explain how people determine the cause of what they observe. For instance, if your friend Charley told you he got a perfect score on his math test, you might find yourself thinking that Charley is very good at math. In that case, you have made a dispositional or person attribution. Alternatively, you might attribute Charley’s success to a situational factor, such as an easy test; in that case you make a situation attribution. Attributions can also be stable or unstable. If you infer that Charley has always been a math whiz, you have made both a person attribution and a stable attribution,also called a person-stable attribution. On the other hand, if you think that Charley studied a lot for this one test you have made a person-unstable attribution. Similarly, if you believe that Ms. Mahoney, Charley’s math teacher, is an easy teacher, you have made a situation-stable attribution. If you think that Ms. Mahoney is a tough teacher who happened to give one easy test, you have made a situation-unstable attribution.

1 Many social psychology experiments use confederates to deceive participants. Confederates are people who, unbeknownst to the participants in the experiment, work with the experimenter.

Table 14.1. How to Use Compliance Strategies to Get Your Teacher to Postpone a Test by One Day

|

Compliance Strategy |

Definition |

Example |

|

Foot-in-the-door |

A small request is followed by a larger request. |

First ask for a little time to review by asking questions in class. After your teacher says yes, ask if the test could be postponed by one day. |

|

Door-in-the-face |

An unrealistically large request is followed by a smaller request. |

First ask if the test could be postponed by one week. After your teacher says no, ask if the test could be postponed by one day. |

|

Norms of reciprocity |

People have the tendency to feel obligated to reciprocate kind behavior. |

First bring your teacher his or her favorite snack. Then ask if the test could be postponed by one day. |

Harold Kelley put forth a theory that explains the kind of attributions people make based on three kinds of information: consistency, distinctiveness, and consensus. Consistency refers to how similarly the individual acts in the same situation over time. How does Charley usually do on his math tests? Distinctiveness refers to how similar this situation is to other situations in which we have watched Charley. Does Charley do well on all tests? Has he evidenced an aptitude for math in other ways? Consensus asks us to consider how others in the same situation have responded. Did many people get a perfect score on the math test?

Consensus is a particularly important piece of information to use when determining whether to make a person or situation attribution. If Charley is the only one to earn such a good score on the math test, we seem to have learned something about Charley. Conversely, if everyone earned a high score on the test, we would suspect that something in the situation contributed to that outcome. Consistency, on the other hand, is extremely useful when determining whether to make a stable or unstable attribution. If Charley always aces his math tests, then it seems more likely that Charley is particularly skilled at math than that he happened to study hard for this one test. Similarly, if everyone always does well on Ms. Mahoney’s tests, we would be likely to make the situation-stable attribution that she is an easy teacher. However, if Charley usually scores low in Ms. Mahoney’s class, we will be more likely to make a situation-unstable attribution such as this particular test was easy.

People often have certain ideas or prejudices about other people before they even meet them. These preconceived ideas can obviously affect the way someone acts toward another person. Even more interesting is the idea that the expectations we have about others can influence the way those others behave. Such a phenomenon is called a self-fulfilling prophecy. For instance, if Jon is repeatedly told that Chet, whom he has never met, is really funny, when Jon does finally meet Chet, he may treat Chet in such a way as to elicit the humorous behavior he expected.

A classic study involving self-fulfilling prophecies was Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson’s (1968) “Pygmalion in the Classroom” experiment. They administered a test to elementary school children that supposedly would identify those children who were on the verge of significant academic growth. In reality, the test was a standard IQ test. These researchers then randomly selected a group of children from the population who took the test, and they informed their teachers that these students were ripe for such intellectual progress. Of course, since the children were selected randomly, they did not differ from any other group of children in the school. At the end of the year, the researchers returned to take another measure of the students’ IQ and found that the scores of the identified children had increased more than the scores of their classmates. In some way, the teachers’ expectations that these students would bloom intellectually over the year actually caused the students to outperform their peers.

Attributional Biases

Although people are quite good at sifting through all the data that bombards them and then making attributions, you will probably not be surprised to learn that errors are not uncommon. Moreover, people tend to make the same kinds of errors. A few typical biases are the fundamental attribution error, false-consensus effect, self-serving bias, and the just-world belief.

When looking at the behavior of others, people tend to overestimate the importance of dispositional factors and underestimate the role of situational factors. This tendency is known as the fundamental attribution error. Say that you go to a party where you are introduced to Claude, a young man you have never met before. Although you attempt to engage Claude in conversation, he is unresponsive. He looks past you and, soon after, seizes upon an excuse to leave. Most people would conclude that Claude is an unfriendly person. Few consider that something in the situation may have contributed to Claude’s behavior. Perhaps Claude just had a terrible fight with his girlfriend, Isabelle. Maybe on the way to the party he had a minor car accident. The point is that people systematically seem to overestimate the role of dispositional factors in influencing another person’s actions.

Interestingly, people do not evidence this same tendency in explaining their own behaviors. Claude knows that he is sometimes extremely outgoing and warm. Since people get to view themselves in countless situations, they are more likely to make situational attributions about themselves than about others. Everyone has been shy and aloof at times, and everyone has been friendly. Thus, people are more likely to say that their own behavior depends upon the situation.

One caveat must be added to our discussion of the fundamental attribution error. The fundamental attribution was named fundamental because it was believed to be so widespread. However, many cross-cultural psychologists have argued that the fundamental attribution error is far less likely to occur in collectivist cultures than in individualistic cultures. In an individualistic culture, like the American culture, the importance and uniqueness of the individual is stressed. In more collectivist cultures, like Japanese culture, a person’s link to various groups such as family or company is stressed. Cross-cultural research suggests that people in collectivist cultures are less likely to commit the fundamental attribution error, perhaps because they are more attuned to the ways that different situations influence their own behavior.

Students often confuse self-serving bias and self-fulfilling prophecies, ostensibly because they both contain the word self. Self-serving bias is the tendency to overstate one’s role in a positive venture and underestimate it in a failure. Thus, people serve themselves by making themselves look good. Self-fulfilling prophecies, on the other hand, explain how people’s ideas about others can shape the behavior of those others.

The tendency for people to overestimate the number of people who agree with them is called the false-consensus effect. For instance, if Jamal dislikes horror movies, he is likely to think that most other people share his aversion. Conversely, Sabrina, who loves a good horror flick, overestimates the number of people who share her passion.

Self-serving bias is the tendency to take more credit for good outcomes than for bad ones. For instance, a basketball coach would be more likely to emphasize her or his role in the team’s championship win than in their heartbreaking first-round tournament loss.

Researchers have found that people evidence a bias toward thinking that bad things happen to bad people. This belief in a just world, known simply as the just-world bias, in which misfortunes befall people who deserve them, can be seen in the tendency to blame victims. For example, the woman was raped because she was stupidly walking alone in a dangerous neighborhood. People are unemployed because they are lazy. If the world is just in this manner, then, assuming we view ourselves as good people, we need not fear bad things happening to ourselves.

STEREOTYPES, PREJUDICE, AND DISCRIMINATION

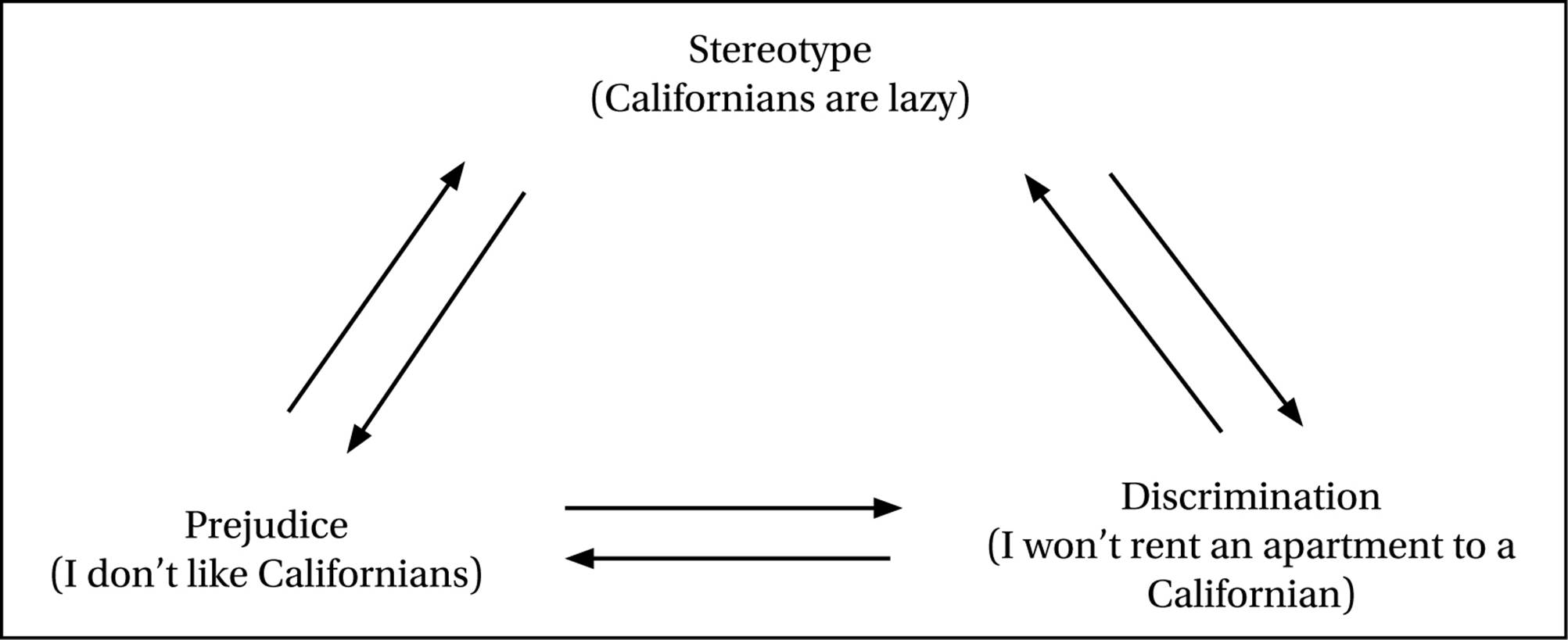

We all have ideas about what members of different groups are like, and these expectations may influence the way we interact with members of these groups. We call these ideas stereotypes. Stereotypes may be either negative or positive and can be applied to virtually any group of people (for example, racial, ethnic, geographic). For instance, people often stereotype New Yorkers as pushy, unfriendly, and rude and Californians as easygoing and attractive. Some cognitive psychologists have suggested that stereotypes are basically schemata about groups. People who distinguish between stereotypes and group schemata argue that the former are more rigid and more difficult to change than the latter.

Prejudice is an undeserved, usually negative, attitude toward a group of people. Stereotyping can lead to prejudice when negative stereotypes (those rude New Yorkers) are applied uncritically to all members of a group (she is from New York, therefore she must be rude) and a negative attitude results.

Ethnocentrism, the belief that one’s culture (for example, ethnic, racial) is superior to others, is a specific kind of prejudice. People become so used to their own cultures that they see them as the norm and use them as the standard by which to judge other cultures. Many people look down upon others who don’t dress the same, eat the same foods, or worship the same God in the same way that they do.

While prejudice is an attitude, discrimination involves an action. When one discriminates, one acts on one’s prejudices. If I dislike New Yorkers, I am prejudiced, but if I refuse to hire New Yorkers to work in my company, I am engaging in discrimination. Unfortunately, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination all reinforce one another. People’s beliefs and attitudes influence each other and guide people’s behavior. In addition, when people act in discriminatory ways, they are motivated to strengthen their prejudices and stereotypes to justify their behavior.

Table 14.2. The Vicious Cycle of Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination

TIP

Students have difficulty distinguishing between prejudice and discrimination. Remember, the former is an attitude and the latter is a behavior.

People tend to see members of their own group, the in-group, as more diverse than members of other groups, out-groups. This phenomenon is often referred to as out-group homogeneity. For example, as a New Yorker myself, I know that while some New Yorkers are indeed pushy and rude, most are not. I know many well-mannered and deferential New Yorkers as well as short New Yorkers, tall New Yorkers, honest New Yorkers, and dishonest New Yorkers. While we all have extensive experience with the members of our own groups, we lack that degree of familiarity with other groups and therefore tend to see them as more similar. In addition, researchers have documented a preference for members of one’s own group, a kind of in-group bias. In-group bias is thought to stem from people’s belief that they themselves are good people. Therefore, the people with whom they share group membership are thought to be good as well.

Origin of Stereotypes and Prejudice

Many different theories attempt to explain how people become prejudiced. Some psychologists have suggested that people naturally and inevitably magnify differences between their own group and others as a function of the cognitive process of categorization. By taking into account the in-group bias discussed above, this idea suggests that people cannot avoid forming stereotypes.

Social learning theorists stress that stereotypes and prejudice are often learned through modeling. Children raised by parents who express prejudices may be more likely to embrace such prejudices themselves. Conversely, this theory suggests that prejudices could be unlearned by exposure to different models.

Combating Prejudice

One theory about how to reduce prejudice is known as the contact theory. The contact theory, as its name suggests, states that contact between hostile groups will reduce animosity, but only if the groups are made to work toward a goal that benefits all and necessitates the participation of all. Such a goal is called a superordinate goal.

Muzafer Sherif’s (1966) camp study (also known as the Robbers Cave study) illustrates both how easily out-group bias can be created and how superordinate goals can be used to unite formerly antagonistic groups. He conducted a series of studies at a summer camp. He first divided the campers into two groups and arranged for them to compete in a series of activities. This competition was sufficient to create negative feelings between the groups. Once such prejudices had been established, Sherif staged several camp emergencies that required the groups to cooperate. The superordinate goal of solving the crises effectively improved relations between the groups.

A number of educational researchers have attempted to use the contact theory to reduce prejudices between members of different groups in school. One goal of most cooperative learning activities is to bring members of different social groups into contact with one another as they work toward a superordinate goal, the assigned task.

AGGRESSION AND ANTISOCIAL BEHAVIOR

Another major area of study for social psychologists is aggression and antisocial behavior. Psychologists distinguish between two types of aggression: instrumental aggression and hostile aggression. Instrumental aggression is when the aggressive act is intended to secure a particular end. For example, if Bobby wants to hold the doll that Carol is holding and he kicks her and grabs the doll, Bobby has engaged in instrumental aggression. Hostile aggression, on the other hand, has no such clear purpose. If Bobby is simply angry or upset and therefore kicks Carol, his aggression is hostile aggression.

Many theories exist about the cause of human aggression. Freud linked aggression to Thanatos, the death instinct. Sociobiologists suggest that the expression of aggression is adaptive under certain circumstances. One of the most influential theories, however, is known as the frustration-aggression hypothesis. This hypothesis holds that the feeling of frustration makes aggression more likely. Considerable experimental evidence supports it. Another common theory is that the exposure to aggressive models makes people aggressive as illustrated by Bandura, Ross, and Ross’s (1963) classic Bobo doll experiment (see the modeling section in Chapter 6 for more information).

PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR

While social psychologists have devoted a lot of time and effort to studying antisocial behavior, they have also studied the factors that make people more likely to help one another. Such helping behavior is termed prosocial behavior. Much of the research in this area has focused on bystander intervention, the conditions under which people nearby are more and less likely to help someone in trouble.

The vicious murder of Kitty Genovese in Kew Gardens, New York, committed within view of at least 38 witnesses, none of whom intervened, led John Darley and Bibb Latane to explore how people decided whether or not to help others in distress. Counterintuitively, the larger the number of people who witness an emergency situation, the less likely any one is to intervene. This finding is known as the bystander effect. One explanation for this phenomenon is called diffusion of responsibility. The larger the group of people who witness a problem, the less responsible any one individual feels to help. People tend to assume that someone else will take action so they need not do so. Another factor contributing to the bystander effect is known as pluralistic ignorance. People seem to decide what constitutes appropriate behavior in a situation by looking to others. Thus, if no one in a classroom seems worried by the black smoke coming through the vent, each individual concludes that taking no action is the proper thing to do.

ATTRACTION

Social psychologists also study what factors increase the chance that people will like one another. A significant body of research indicates that we like others who are similar to us, with whom we come into frequent contact, and who return our positive feelings. These three factors are often referred to as similarity, proximity, and reciprocal liking. Although conventional wisdom holds that opposites attract, psychological research indicates that we are drawn to people who are similar to us, those who share our attitudes, backgrounds, and interests. Proximity means nearness. As is suggested by the mere-exposure effect, the greater the exposure one has to another person, the more one generally comes to like that person. In addition, only by talking to someone can one identify the similarities that will draw the pair closer together. Finally, every reader has probably had the misfortune to experience that liking someone who scorns you is not enjoyable. Thus, the more someone likes you, the more you will probably like that person.

Not surprisingly, people are also attracted to others who are physically attractive. In fact, the benefits of being nice-looking extend well beyond the realm of attraction. Research has demonstrated that good-looking people are perceived as having all sorts of positive attributes including better personalities and greater job competence.

Psychologists have also devoted tremendous time and attention to the concept of love. While research seems to indicate that the emotion of love qualitatively differs from liking and a number of theories about love have been proposed, the subject has proven difficult to explain adequately.

A term often employed as part of liking and loving studies is self-disclosure. One self-discloses when one shares a piece of personal information with another. Close relationships with friends and lovers are often built through a process of self-disclosure. On the path to intimacy, one person shares a detail of his or her life and the other reciprocates by exposing a facet of his or her own.

THE INFLUENCE OF OTHERS ON AN INDIVIDUAL’S BEHAVIOR

A major area of research in social psychology is how an individual’s behavior can be affected by another’s actions or even merely by another person’s presence. A number of studies have illustrated that people perform tasks better in front of an audience than they do when they are alone. They yell louder, run faster, and reel in a fishing rod more quickly. This phenomenon, that the presence of others improves task performance, is known as social facilitation.Later studies, however, found that when the task being observed was a difficult one rather than a simple, well-practiced skill, being watched by others actually hurt performance, a finding known as social impairment.

Conformity has been an area of much research as well. Conformity is the tendency of people to go along with the views or actions of others. Solomon Asch (1951) conducted one of the most interesting conformity experiments. He brought participants into a room of confederates and asked them to make a series of simple perceptual judgments. Asch showed the participants three vertical lines of varying sizes and asked them to indicate which one was the same length as a different target line. All members of the group gave their answers aloud, and the participant was always the last person to speak. All of the trials had a clear, correct answer. However, on some of them, all of the confederates gave the same, obviously incorrect judgment. Asch was interested in what the participants would do. Would they conform to a judgment they knew to be wrong or would they differ from the group? Asch found that in approximately one-third of the cases when the confederates gave an incorrect answer, the participants conformed. Furthermore, approximately 70 percent of the participants conformed on at least one of the trials. In general, studies have suggested that conformity is most likely to occur when a group’s opinion is unanimous. Although it would seem that the larger the group, the greater conformity that would be expressed, studies have shown that groups larger than three (in addition to the participant) do not significantly increase the tendency to conform.

While conformity involves following a group without being explicitly told to do so, obedience studies have focused on participants’ willingness to do what another asks them to do. Stanley Milgram (1974) conducted the classic obedience studies. His participants were told that they were taking part in a study about teaching and learning, and they were assigned to play the part of teacher. The learner, of course, was a confederate. As teacher, each participant’s job was to give the learner an electric shock for every incorrect response. The participant sat behind a panel of buttons each labeled with the number of volts, beginning at 15 and increasing by increments of 15 up to 450. The levels of shock were also described in words ranging from mild up to XXX. In reality, no shocks were delivered; the confederate pretended to be shocked. As the level of the shocks increased, the confederate screamed in pain, said he suffered from a heart condition, and eventually fell silent. Milgram was interested in how far participants would go before refusing to deliver any more shocks. The experimenter watched the participant and, if questioned, gave only a few stock answers, such as “Please continue.” Contrary to the predictions of psychologists who Milgram polled prior to the experiment, over 60 percent of the participants obeyed the experimenter and delivered all the possible shocks.

Milgram replicated his study with a number of interesting twists. He found that he could decrease participants’ compliance by bringing them into closer contact with the confederates. Participants who could see the learners gave fewer shocks than participants who could only hear the learners. The lowest shock rates of all were administered by participants who had to force the learner’s hand onto the shock plate. However, even in that last condition, approximately 30 percent delivered all of the shocks. When the experimenter left in the middle of the experiment and was replaced by an assistant, obedience also decreased. Finally, when other confederates were present in the room and they objected to the shocks, the percentage of participants who quit in the middle of the experiment skyrocketed.

One final note about the Milgram experiment bears mentioning. It has been severely criticized on ethical grounds, and such an experiment would surely not receive the approval of an institutional review board (IRB) today. When debriefed, many participants learned that had the shocks been real, they would have killed the learner. Understandably, some people were profoundly disturbed by this insight.

Table 14.3. Famous Social Psychology Experiments

|

Experimenter |

Topic |

Major Finding |

|

LaPiere |

Attitudes |

Attitudes don’t always predict behavior; establishments that served a Chinese couple later reported they would refuse such a couple service. |

|

Festinger and Carlsmith |

Cognitive dissonance |

Changing one’s behavior can lead to a change in attitudes; people who described a boring task as interesting for $1 in compensation later reported liking the task more than people who were paid $20. |

|

Rosenthal and Jacobson |

Self-fulfilling prophecy |

One person’s attitudes can elicit a change in another person’s behavior; teachers’ positive expectations led to increases in students’ IQ scores. |

|

Sherif |

Superordinate goals |

Intergroup prejudice can be reduced through working toward superordinate goals; campers in unfriendly, competing groups came to have more positive feelings about one another after working together to solve several camp-wide problems. |

|

Darley and Latane |

Bystander effect |

The more people that witness an emergency, the less likely any one person is to help; in one study, college students who thought they were the only person to overhear a peer have a seizure were more likely to help than students who thought others heard the seizure, too. |

|

Asch |

Conformity |

People are loathe to contradict the opinions of a group; 70% of people reported at least one obviously incorrect answer. |

|

Milgram |

Obedience |

People tend to obey authority figures; 60% of participants thought they delivered the maximum possible level of shock. |

|

Zimbardo |

Roles, deindividuation |

Roles are powerful and can lead to deindividuation; college students role-playing prisoners and guards acted in surprisingly negative and hostile ways. |

GROUP DYNAMICS

We are all members of many different groups. The students in your school are a group, a baseball team is a group, and the lawyers at a particular firm are a group. Some groups are more cohesive than others and exert more pressure on their members. All groups have norms, rules about how group members should act. For example, the lawyers at the firm mentioned above may have rules governing appropriate work dress. Within groups is often a set of specific roles. On a baseball team, for instance, the players have different, well-defined roles such as pitcher, shortstop, and center fielder.

Sometimes people take advantage of being part of a group by social loafing. Social loafing is the phenomenon when individuals do not put in as much effort when acting as part of a group as they do when acting alone. One explanation for this effect is that when alone, an individual’s efforts are more easily discernible than when in a group. Thus, as part of a group, a person may be less motivated to put in an impressive performance. In addition, being part of a group may encourage members to take advantage of the opportunity to reap the rewards of the group effort without taxing themselves unnecessarily.

Group polarization is the tendency of a group to make more extreme decisions than the group members would make individually. Studies about group polarization usually have participants give their opinions individually, then group them to discuss their decisions, and then have the group make a decision. Explanations for group polarization include the idea that in a group, individuals may be exposed to new, persuasive arguments they had not thought of themselves and that the responsibility for an extreme decision in a group is diffused across the group’s many members.

Groupthink, a term coined by Irving Janis, describes the tendency for some groups to make bad decisions. Groupthink occurs when group members suppress their reservations about the ideas supported by the group. As a result, a kind of false unanimity is encouraged, and flaws in the group’s decisions may be overlooked. Highly cohesive groups involved in making risky decisions seem to be at particular risk for groupthink.

Sometimes people get swept up by a group and do things they never would have done if on their own such as looting or rioting. This loss of self-restraint occurs when group members feel anonymous and aroused, and this phenomenon is known as deindividuation.

One famous experiment that showed not only how such conditions can cause people to deindividuate but also the effect of roles and the situation in general, is Phillip Zimbardo’s prison experiment. Zimbardo assigned a group of Stanford students to either play the role of prison guard or prisoner. All were dressed in uniforms and the prisoners were assigned numbers. The prisoners were locked up in the basement of the psychology building, and the guards were put in charge of their treatment. The students took to their assigned roles perhaps too well, and the experiment had to be ended early because of the cruel treatment the guards were inflicting on the prisoners.

PRACTICE QUESTIONS

Directions: Each of the questions or incomplete statements below is followed by five suggested answers or completions. Select the one that is best in each case.

1.Which of the following suggestions is most likely to reduce the hostility felt between antagonistic groups?

(A)force the groups to spend a lot of time together

(B)encourage the groups to avoid each other as much as possible

(C)give the groups a task that cannot be solved unless they work together

(D)set up a program in which speakers attempt to persuade the groups to get along

(E)punish the groups whenever they treat each other badly

2.On Monday, Tanya asked her teacher to postpone Tuesday’s test until Friday. After her teacher flatly refused, Tanya asked the teacher to push the test back one day, to Wednesday. Tanya is using the compliance strategy known as

(A)foot-in-the-door.

(B)norms of reciprocity.

(C)compromise.

(D)strategic bargaining.

(E)door-in-the-face.

3.In the Milgram studies, the dependent measure was the

(A)highest level of shock supposedly administered.

(B)location of the learner.

(C)length of the line.

(D)number of people in the group.

(E)instructions given by the experimenter.

4.The tendency of people to look toward others for cues about the appropriate way to behave when confronted by an emergency is known as

(A)bystander intervention.

(B)pluralistic ignorance.

(C)modeling.

(D)diffusion of responsibility.

(E)conformity.

5.Advertisements are made more effective when the communicators are

I.attractive.

II.famous.

III.perceived as experts.

(A)II only

(B)III only

(C)I and II

(D)II and III

(E)I, II, and III

6.Your new neighbor seems to know everything about ancient Greece that your social studies teacher says during the first week of school. You conclude that she is brilliant. You do not consider that she might already have learned about ancient Greece in her old school. You are evidencing

(A)the self-fulfilling prophecy effect.

(B)pluralistic ignorance.

(C)confirmation bias.

(D)the fundamental attribution error.

(E)cognitive dissonance.

7.In Asch’s conformity study, approximately what percentage of participants gave at least one incorrect response?

(A)30

(B)40

(C)50

(D)60

(E)70

8.Janine has always hated the color orange. However, once she became a student at Princeton, she began to wear a lot of orange Princeton Tiger clothing. The discomfort caused by her long-standing dislike of the color orange and her current ownership of so much orange-and-black-striped clothing is known as

(A)cognitive dissonance.

(B)contradictory concepts.

(C)conflicting motives.

(D)opposing cognitions.

(E)inconsistent ideas.

9.When Pasquale had his first oboe solo in the orchestra concert, his performance was far worse than it was when he rehearsed at home. A phenomenon that helps explain Pasquale’s poor performance is known as

(A)social loafing.

(B)groupthink.

(C)deindividuation.

(D)social impairment.

(E)diffusion of responsibility.

10.Kelley’s attribution theory says that people use which of the following kinds of information in explaining events?

(A)conformity, reliability, and validity

(B)consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness

(C)uniqueness, explanatory power, and logic

(D)salience, importance, and reason

(E)distinctiveness, conformity, and salience

11.After your school’s football team has a big win, students in the halls can be heard saying “We are awesome.” The next week, after the team loses to the last-place team in the league, the same students lament that “They were terrible.” The difference in these comments illustrates

(A)the fundamental attribution error.

(B)self-serving bias.

(C)the self-fulfilling prophecy effect.

(D)the false consensus effect.

(E)conformity.

12.Which of the following is the best example of prejudice?

(A)Billy will not let girls play on his hockey team.

(B)Santiago dislikes cheerleaders.

(C)Athena says she can run faster than anybody on the playground.

(D)Mr. Tamp calls on boys more often than girls.

(E)Ginny thinks all Asians are smart.

13.On their second date, Megan confides in Francisco that she still loves to watch Rugrats. He, in turn, tells her that he still cries when he watches Bambi. These two young lovers will be brought closer together through this process of

(A)self-disclosure.

(B)deindividuation.

(C)in-group bias.

(D)dual sharing.

(E)open communication.

14.On the first day of class, Mr. Simpson divides his class into four competing groups. On the fifth day of school, Jody is sent to the principal for kicking members of the other groups. Mr. Simpson can be faulted for encouraging the creation of

(A)group polarization.

(B)deindividuation.

(C)out-group bias.

(D)superordinate goals.

(E)groupthink.

15.Rosenthal and Jacobson’s “Pygmalion in the Classroom” study showed that

(A)people’s expectations of others can influence the behavior of those others.

(B)attitudes are not always good predictors of behavior.

(C)contact is not sufficient to break down prejudices.

(D)people like to think that others get what they deserve.

(E)cohesive groups often make bad decisions.