AP U.S. History Exam 2018

Copyright © 2017 by McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-25-986278-6

MHID: 1-25-986278-X.

The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-1-25-986277-9, MHID: 1-25-986277-1.

eBook conversion by codeMantra

Version 1.0

All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps.

McGraw-Hill Education eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative, please visit the Contact Us page at www.mhprofessional.com.

Trademarks: McGraw-Hill Education, the McGraw-Hill Education logo, 5 Steps to a 5, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of McGraw-Hill Education and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. McGraw-Hill Education is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

AP, Advanced Placement Program, and College Board are registered trademarks of the College Board, which was not involved in the production of, and does not endorse, this product.

The series editor was Grace Freedson, and the project editor was Del Franz.

Series design by Jane Tenenbaum.

TERMS OF USE

This is a copyrighted work and McGraw-Hill Education and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill Education’s prior consent. You may use the work for your own noncommercial and personal use; any other use of the work is strictly prohibited. Your right to use the work may be terminated if you fail to comply with these terms.

THE WORK IS PROVIDED “AS IS.” McGRAW-HILL EDUCATION AND ITS LICENSORS MAKE NO GUARANTEES OR WARRANTIES AS TO THE ACCURACY, ADEQUACY OR COMPLETENESS OF OR RESULTS TO BE OBTAINED FROM USING THE WORK, INCLUDING ANY INFORMATION THAT CAN BE ACCESSED THROUGH THE WORK VIA HYPERLINK OR OTHERWISE, AND EXPRESSLY DISCLAIM ANY WARRANTY, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. McGraw-Hill Education and its licensors do not warrant or guarantee that the functions contained in the work will meet your requirements or that its operation will be uninterrupted or error free. Neither McGraw-Hill Education nor its licensors shall be liable to you or anyone else for any inaccuracy, error or omission, regardless of cause, in the work or for any damages resulting therefrom. McGraw-Hill Education has no responsibility for the content of any information accessed through the work. Under no circumstances shall McGraw-Hill Education and/or its licensors be liable for any indirect, incidental, special, punitive, consequential or similar damages that result from the use of or inability to use the work, even if any of them has been advised of the possibility of such damages. This limitation of liability shall apply to any claim or cause whatsoever whether such claim or cause arises in contract, tort or otherwise.

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction: 5-Step Program

STEP 1 Set Up Your Study Program

1 What You Need to Know About the AP U.S. History Exam

Advanced Placement Program

AP U.S. History Exam

Taking the AP U.S. History Exam

2 Preparing for the AP U.S. History Exam

Getting Started

STEP 2 Determine Your Test Readiness

3 Take a Diagnostic Exam

How to Use the Diagnostic Exam

When to Use the Diagnostic Exam

Conclusion (After the Exam)

STEP 3 Develop Strategies for Success

4 Mastering Skills and Understanding Themes for the Exam

The AP U.S. History Exam

Historical Analytical Skills, Historical Themes, and Exam Questions

5 Strategies for Approaching Each Question Type

Multiple-Choice Questions

Short-Answer Questions

Document-Based Question (DBQ)

Long-Essay Question

Using Primary Source Documents

STEP 4 Review the Knowledge You Need to Score High

6 Settling of the Western Hemisphere (1491–1607)

Native America

The Europeans Arrive

Chapter Review

7 Colonial America (1607–1650)

New France

English Interest in America

Effects of European Settlement

Chapter Review

8 British Empire in America: Growth and Conflict (1650–1750)

Part of an Empire

Growth of Slavery

Political Unrest in the Colonies

Salem Witch Trials

Imperial Wars

American Self-Government

Salutary Neglect

First Great American Religious Revival

Chapter Review

9 Resistance, Rebellion, and Revolution (1750–1775)

War in the West

Defeat of New France

The British Need Money

Stamp Act Crisis

Townshend Acts

Boston Massacre

Boston Tea Party

Intolerable Acts

First Continental Congress

Chapter Review

10 American Revolution and the New Nation (1775–1787)

Lexington and Concord

Second Continental Congress

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

Declaration of Independence

Reactions to Independence

Balance of Forces

The War in the North

The Saratoga Campaign

The War in the South

The Treaty of Paris

New State Constitutions and the Articles of Confederation

Financial Problems

Northwest Ordinances

Shays’ Rebellion

Chapter Review

11 Establishment of New Political Systems (1787–1800)

The Constitutional Convention

The Ratification Battle

The Bill of Rights

The Birth of the Party System

Hamilton’s Economic Program

Effects of the French Revolution

Washington’s Foreign Policy

The Presidency of John Adams

Chapter Review

12 Jeffersonian Revolution (1800–1820)

Election of 1800

An Assertive Supreme Court

A New Frontier

The Louisiana Purchase

Burr’s Conspiracy

Renewal of War in Europe

The War of 1812

The End of the War

A Federalist Debacle and the Era of Good Feelings

Henry Clay and the American System

Missouri Compromise

Chapter Review

13 Rise of Manufacturing and the Age of Jackson (1820–1845)

The Rise of Manufacturing

The Monroe Doctrine

Native American Removal

The Transportation Revolution and Religious Revival

An Age of Reform

Jacksonian Democracy

The Nullification Controversy

The Bank War

The Whig Party and the Second Party System

Chapter Review

14 Union Expanded and Challenged (1835–1860)

Manifest Destiny

The Alamo and Texas Independence

Expansion and the Election of 1844

The Mexican War

Political Consequences of the Mexican War

The Political Crisis of 1850

Aftermath of the Compromise of 1850

Franklin Pierce in the White House

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

“Bleeding Kansas”

The Dred Scott Decision

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

John Brown and Harpers Ferry

The Election of 1860

Chapter Review

15 Union Divided: The Civil War (1861–1865)

North and South on the Brink of War

Searching for Compromise

Gunfire at Fort Sumter

Opening Strategies

The Loss of Illusions

Union Victories in the West

The Home Fronts

The Emancipation Proclamation

The Turn of the Tide

War Weariness

The End of the War

16 Era of Reconstruction (1865–1877)

Lincoln and Reconstruction

Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction

Efforts to Help the Freedmen

Radical Reconstruction

The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Final Phase of Radical Reconstruction

The End of Reconstruction

Chapter Review

17 Western Expansion and Its Impact on the American Character (1860–1895)

Government Encouragement of Western Settlement

Challenges for Western Farmers

Agricultural Innovation

Women and Minorities on the Agricultural Frontier

The Mining and Lumbering Frontier

The Ranching Frontier

The End of Native American Independence

Agrarian Anger and Populism

The Gold Standard

The Grange and Farmers’ Alliances

The Populist Revolt

Populism and the Election of 1896

The Idea of the West

Chapter Review

18 America Transformed into the Industrial Giant of the World (1870–1910)

An Industrial Revolution

Changes in American Industry

A Changing Workplace

Big Business

The Emergence of Labor Unions

Uneven Affluence

The New Immigration

The Rise of the Modern American City

Gilded Age Politics

Social Criticism in the Gilded Age

Chapter Review

19 Rise of American Imperialism (1890–1913)

Postwar Diplomacy

Acquiring Hawaii

The New Imperialism

The Spanish–American War

Combat in the Philippines and Cuba

The Cuban Conundrum

The Debate over Empire

The Panama Canal

The Roosevelt Corollary

Chapter Review

20 Progressive Era (1895–1914)

Roots of Progressivism

Progressive Objectives

Urban Progressivism

State-Level Progressivism

Progressivism and Women

Workplace Reform

Theodore Roosevelt’s Square Deal

Taft and Progressivism

The Election of 1912

Wilson and Progressivism

Assessing Progressivism

Chapter Review

21 United States and World War I (1914–1921)

War and American Neutrality

Growing Ties to the Allies

The Breakdown of German-American Relations

America in the War

The American Expeditionary Force in France

The Home Front

Regulating Thought

Social Change

Wilson and the Peace

Woodrow Wilson’s Defeat

Chapter Review

22 Beginning of Modern America: The 1920s

The Prosperous Twenties

The Republican “New Era”

Warren G. Harding as President

President Calvin Coolidge

The Election of 1928

The City Versus the Country in the 1920s

Popular Culture in the 1920s

Jazz Age Experimentation and Rebellion

The Growth of the Mass Media

A Lost Generation?

Chapter Review

23 Great Depression and the New Deal (1929–1939)

American Economy of the 1920s: Roots of the Great Depression

Stock Market Crash

Social Impact of the Great Depression

Hoover Administration and the Depression

1932 Presidential Election

First Hundred Days

Second New Deal

Presidential Election of 1936

Opponents of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal

Last Years of the New Deal

Effects of the New Deal

New Deal Culture

Chapter Review

24 World War II (1933–1945)

American Foreign Policy in the 1930s

United States and the Middle East in the Interwar Era

Presidential Election of 1940 and Its Aftermath

Attack on Pearl Harbor

America Enters the War

Role of the Middle East in World War II

War Against Japan

Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb

Home Front During the War

Discrimination During the War

Chapter Review

25 Origins of the Cold War (1945–1960)

First Cracks in the Alliance: 1945

The Iron Curtain

Marshall Plan

Berlin: The First Cold War Crisis

1949: A Pivotal Year in the Cold War

Middle East in the Early Years of the Cold War

Cold War at Home

Heating of the Cold War: Korea

Rise of McCarthyism

Cold War Policies of President Eisenhower

Dangerous Arms Buildup

Chapter Review

26 Prosperity and Anxiety: The 1950s

Economic Growth and Prosperity

Political Developments of the Postwar Era

Civil Rights Struggles of the Postwar Period

Conformity of the Suburbs

Chapter Review

27 America in an Era of Turmoil (1960–1975)

1960 Presidential Election

Domestic Policies under Kennedy and Johnson

Struggle of Black Americans: From Nonviolence to Black Power

Rise of Feminism

Cold War in the 1960s

Vietnam War and Its Impact on American Society

Chapter Review

28 Decline and Rebirth (1968–1988)

Presidency of Richard Nixon

Watergate Affair

Presidency of Gerald Ford

Presidency of Jimmy Carter

Election of 1980

Presidency of Ronald Reagan

Chapter Review

29 Prosperity and a New World Order (1988–2000)

1988 Election

Presidency of George H. Bush

1992 Election

Presidency of Bill Clinton

2000 Presidential Election

Chapter Review

30 Threat of Terrorism, Increase of Presidential Power, and Economic Crisis (2001–2014)

9/11 and Its Aftermath

Events Leading Up to the American Invasion of Iraq

Operation Iraqi Freedom

Effects of the War at Home

Victory of Conservatism in the Bush Era

United States in Transition: 2007–2008

Obama Presidency

Election of 2012

President Obama’s Second Term

The Election of 2016

Chapter Review

31 Contemporary America: Evaluating the “Big Themes”

STEP 5 Build Your Test-Taking Confidence

AP U.S. History Practice Exam 1

AP U.S. History Practice Exam 2

Glossary

Bibliography

Websites

PREFACE

So, you have decided to take AP U.S. History. Prepare to be continually challenged in this course: this is the only way you will attain the grade that you want on the AP exam in May. Prepare to read, to read a lot, and to read critically; almost all students successful in AP U.S. History say this is a necessity. Prepare to analyze countless primary source documents; being able to do this is critical for success in the exam as well. Most important, prepare to immerse yourself in the great story that is U.S. history. As your teacher will undoubtedly point out, it would be impossible to make up some of the people and events you will study in this class. What really happened is much more interesting!

This study guide will assist you along the journey of AP U.S. History. The chapter review guides give you succinct overviews of the major events of U.S. history. At the end of each chapter is a list of the major concepts, a time line, and multiple-choice and short-answer review questions for that chapter. In addition, a very extensive glossary is included at the back of this manual. All of the boldface words throughout the book can be found in the glossary (it would also be a good study technique to review the entire glossary before taking the actual AP exam).

The first five chapters of the manual describe the AP test itself and suggest some test-taking strategies. There are also two entire sample tests, with answers. These allow you to become totally familiar with the format and nature of the questions that will appear on the exam. On the actual testing day you want absolutely no surprises!

In the second chapter, you will also find time lines for three approaches to preparing for the exam. It is obviously suggested that your preparation for the examination be a year-long process; for those students unable to do that, two alternative calendars also appear. Many students also find that study groups are very beneficial in studying for the AP test. Students who have been successful on the AP test oftentimes form these groups very early in the school year.

It should also be noted that the AP U.S. History exam that you will be taking may be different than the one that your older brother or sister took in the past. The format of the exam changed in 2015. We will outline the test in detail in the first several chapters. Please do not use old study guides or review sheets that were used to prepare for prior tests; these do not work anymore!

We hope this manual helps you in achieving the “perfect 5.” That score is sitting out there, waiting for you to reach for it.

INTRODUCTION: 5-STEP PROGRAM

The Basics

This guide provides you with the specific format of the AP U.S. History exam, three sample AP U.S. History tests, and a comprehensive review of major events and themes in U.S. history. After each review chapter, you will find a list of the major concepts, a time line, and several review multiple-choice and short-answer questions.

Reading this guide is a great start to getting the grade you want on the AP U.S. History test, but it is important to read on your own as well. Several groups of students who have all gotten a 5 on the test maintain that the key to success is to read as much as you possibly can on U.S. history.

Reading this guide will not guarantee you a 5 when you take the U.S. History exam in May. However, by carefully reviewing the format of the exam and the test-taking strategies provided for each section, you will definitely be on your way! The review section that outlines the major developments of U.S. history should augment what you have learned from your regular U.S. history textbook. This book won’t “give” you a 5, but it can certainly point you firmly in that direction.

Organization of the Book

This guide conducts you through the five steps necessary to prepare yourself for success on the exam. These steps will provide you with many skills and strategies vital to the exam and the practice that will lead you toward the perfect 5.

In this introductory chapter we will explain the basic five-step plan, which is the focus of this entire book. The material in Chapter 1 will give you information you need to know about the AP U.S. History exam. In Chapter 2 three different approaches will be presented to prepare for the actual exam; study them all and then pick the one that works best for you. Chapter 3 contains a practice AP U.S. History exam; this is an opportunity to experience what the test is like and to have a better idea of your strengths and weaknesses as you prepare for the actual exam. Chapter 4 describes historical skills and themes emphasized in the exam. Chapter 5 contains a number of tips and suggestions about the different types of questions that appear on the actual exam. We will discuss ways to approach the multiple-choice questions, the short-answer questions, the document-based question (DBQ), and the long-essay question. Almost all students note that knowing how to approach each type of question is crucial.

For some of you, the most important part of this manual will be found in Chapters 6 through 31, which contain a review of U.S. history from the European exploration of the Americas to the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Undoubtedly, you have studied much of the material included in these chapters. However, these review chapters can help highlight certain important material that you may have missed or forgotten from your AP History class. At the end of each chapter, you will also find a list of the major concepts, time line of important events discussed in the chapter, and multiple-choice and short-answer review questions.

After these review chapters you will find two complete practice exams, including multiple-choice questions, short-answer questions, and essays. Correct answers and explanations for these answers are also included. Take one of the exams and evaluate your success; review any material that you had trouble with. Then take the second exam and use the results to guide your additional study. At the back of the manual is a glossary that defines all of the boldface words found in the review chapters. Use this to find the meaning of a specific term you might be unfamiliar with; some students find reviewing the entire glossary a useful method of reviewing for the actual exam.

Five-Step Program

Step 1: Set Up Your Study Program

In Step 1, you will read a brief overview of the AP U.S. History exam, including an outline of the topics that might be covered on the test itself. You will also follow a process to help determine which of the following preparation programs is right for you:

• Full school year: September through May

• One semester: January through May

• Six weeks: Basic Training for the Exam

Step 2: Determine Your Test Readiness

Step 2 provides you with a diagnostic exam to assess your current level of understanding. This exam will let you know about your current level of preparedness and on which areas and periods you should focus your study.

• Take the diagnostic exam slowly and analyze each question. Do not worry about how many questions you get right. Hopefully the exam will boost your confidence.

• Review the answers and explanations following the exam, so that you see what you do and do not yet fully know and understand.

Step 3: Develop Strategies for Success

Step 3 provides strategies and techniques that will help you do your best on the exam. These strategies cover the multiple-choice, short-answer, and the two different essay parts of the test. These tips come from discussions with both AP U.S. History students and teachers. In this section you will:

• Learn the skills and themes emphasized in the exam.

• Learn how to read and analyze multiple-choice questions.

• Learn how to answer multiple-choice questions, including whether or not to guess.

• Learn how to respond to short-answer questions.

• Learn how to plan and write both types of essay questions.

Step 4: Review the Knowledge You Need to Score High

Step 4 makes up the majority of this book. In this step you will review the important names, dates, and themes of American history. Obviously, not all of the material included in this book will be on the AP exam. However, this book is a good overview of the content studied in a “typical” AP U.S. History course. Some of you are presently taking AP courses that cover more material than is included in this book; some of you are in courses that cover less. Nevertheless, thoroughly reviewing the material in the content section of this book will significantly increase your chance of scoring well.

Step 5: Build Your Test-Taking Confidence

In Step 5, you will complete your preparation by taking two complete practice exams and examining your results on them. It should be noted that the practice exams included in this book do not include questions taken from actual exams; however, these practice exams do include questions that are very similar to the “real thing.”

Graphics Used in This Book

To emphasize particular skills and strategies, we use several icons throughout this book. An icon in the margin will alert you that you should pay particular attention to the accompanying text. We use three icons:

The first icon points out a very important concept or fact that you should not pass over.

The second icon calls your attention to a problem-solving strategy that you may want to try.

The third icon indicates a tip that you might find useful.

Boldface words indicate terms that are included in the glossary at the end of the book. Boldface is also used to indicate the answer to a sample problem discussed in the test. Throughout the book, you will find marginal notes, boxes, and starred areas. Pay close attention to these areas because they can provide tips, hints, strategies, and further explanations to help you reach your full potential.

What You Need to Know About the AP U.S. History Exam

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summary: Learn about the test, what’s on it, how it’s scored, and what benefits you can get from taking it.

Key Ideas

Most colleges will award credit for a score of 4 or 5. Even if you don’t do well enough on the exam to receive college credit, college admissions officials like to see students who have challenged themselves and experienced the college-level coursework of AP courses.

Most colleges will award credit for a score of 4 or 5. Even if you don’t do well enough on the exam to receive college credit, college admissions officials like to see students who have challenged themselves and experienced the college-level coursework of AP courses.

Since 2015, the exam has had a new format. The new exam de-emphasizes the simple memorization of historical facts. Instead, you have to demonstrate an ability to use historical analytical skills and think thematically across time periods in American history.

Since 2015, the exam has had a new format. The new exam de-emphasizes the simple memorization of historical facts. Instead, you have to demonstrate an ability to use historical analytical skills and think thematically across time periods in American history.

In addition to multiple-choice and short-answer questions, the test contains a DBQ (document-based question) and one long-essay question.

In addition to multiple-choice and short-answer questions, the test contains a DBQ (document-based question) and one long-essay question.

Advanced Placement Program

The Advanced Placement (AP) program was begun by the College Board in 1955 to administer standard achievement exams that would allow highly motivated high school students the opportunity to earn college credit for AP courses taken in high school. Today there are 34 different AP courses and exams, with well over 4.5 million exams administered each May.

There are numerous AP courses in the social studies besides U.S. History, including European History, World History, U.S. Government and Politics, Comparative Government, Psychology, and Micro and Macro Economics. The majority of students who take AP courses and exams are juniors and seniors; however, some schools offer AP courses to freshmen and sophomores (AP U.S. History is usually not one of those courses). It is not absolutely necessary to be enrolled in an AP class to take the exam in a specific subject; there are rare cases of students who study on their own for a particular AP examination and do well.

Who Writes the AP Exams? Who Scores Them?

AP exams, including the U.S. History exam, are written by experienced college and secondary school teachers. All questions on the AP exams are field tested before they actually appear on an AP exam. The group that writes the history exam is called the AP U.S. History Development Committee. This group constantly reevaluates the test, analyzing the exam as a whole and on an item-by-item basis.

As noted in the preface, the AP U.S. History exam has undergone a substantial transformation that will take effect beginning with the 2015 test. The College Board has conducted a number of institutes and workshops to ensure that teachers across the United States are well qualified to assist students in preparing for this new exam.

The multiple-choice section of each AP exam is graded by computer, but the free-response questions are scored by humans. A number of college and secondary school teachers of U.S. History get together at a central location in early June to score the free-response questions of the AP U.S. History exam administered the previous month. The scoring of each reader during this procedure is carefully analyzed to ensure that exams are being evaluated in a fair and consistent manner.

AP Scores

Once you have taken the exam and it has been scored, your raw scores will be transformed into an AP grade on a 1-to-5 scale. A grade report will be send to you by the College Board in July. When you take the test, you should indicate the college or colleges that you want your AP scores sent to. The report that the colleges receive contains the score for every AP exam you took this year and the grades that you received on AP exams in prior years. In addition, your scores will be sent to your high school. (Note that it is possible, for a fee, to withhold the scores of any AP exam you have taken from going out to colleges. See the College Board website for more information.)

As noted above, you will be scored on a 1-to-5 scale:

• 5 indicates that you are extremely well qualified. This is the highest possible grade.

• 4 indicates that you are well qualified.

• 3 indicates that you are qualified.

• 2 indicates that you are possibly qualified.

• 1 indicates that you are not qualified to receive college credit.

Benefits of the AP Exam

If you receive a score of a 4 or a 5, you can most likely get actual college credit for the subject that you took the course in; a few colleges will do the same for students receiving a 3. Colleges and universities have different rules on AP scores and credit, so check with the college or colleges that you are considering to determine what credit they will give you for a good score on the AP History exam. Some colleges might exempt you from a freshman-level course based on your score even if they don’t grant credit for the score you received.

The benefits of being awarded college credits before you start college are significant: You can save time in college (by skipping courses) and money (by avoiding paying college tuition for courses you skip). Almost every college encourages students to challenge themselves; if it is possible for you to take an AP course, do it! Even if you do not do well on the actual test—or you decide not to take the AP test—the experience of being in an AP class all year can impress college admissions committees and help you prepare for the more academically challenging work of college.

AP U.S. History Exam

Achieving a good score on the AP U.S. History exam will require you do more than just memorize important dates, people, and events from America’s history. To get a 4 or a 5 you have to demonstrate an ability to utilize specific historical analytical skills when studying history. In addition, you will be asked to demonstrate your ability to think thematically and evaluate specific historical themes across time periods in American history. Every question on the AP U.S. History exam is rooted in these analytical skills and historical themes. You’ll find more information about these analytical skills and historical themes in Chapter 4.

As far as specific content, there is material that you need to know from nine predetermined historical time periods of U.S. history. For each of these time periods, key concepts have been identified. You will be introduced to a concept outline for each of the historical periods in your AP course. You can also find this outline at the College Board’s AP U.S. History website. These concepts are connected to the historical themes and analyzed using historical analytical skills.

To do well on this exam you have to exhibit the ability to do much of the work that “real” historians do. You must know major concepts from every historical time period. You must demonstrate an ability to think thematically when analyzing history, and you must utilize historical thinking skills when doing all of this. The simple memorization of historical facts is given less emphasis in the new exam. This does not mean that you can ignore historical detail. Knowledge of historical information will be crucial in explaining themes in American history. Essentially this exam is changing the focus of what is expected of AP U.S. History students. It is asking you to take a smaller number of historical concepts and to analyze these concepts very carefully. The ability to do this does not necessarily come easily; one of the major functions of this book is to help you “think like a historian.”

Periods of U.S. History

As noted earlier, U.S. history has been divided into specific time periods for the purposes of the AP course. The creators of the AP U.S. History exam have established the following nine historical periods and have also determined approximately how much of the year should be spent on each historical era:

• Period 1: 1491 to 1607. Approximately 5 percent of instructional time should be spent on this period.

• Period 2: 1607 to 1754. Approximately 10 percent of instructional time should be spent on this period.

• Period 3: 1754 to 1800. Approximately 12 percent of instructional time should be spent on this period.

• Period 4: 1800 to 1848. Approximately 10 percent of instructional time should be spent on this period.

• Period 5: 1844 to 1877. Approximately 13 percent of instructional time should be spent on this period.

• Period 6: 1865 to 1898. Approximately 13 percent of instructional time should be spent on this period.

• Period 7: 1890 to 1945. Approximately 17 percent of instructional time should be spent on this period.

• Period 8: 1945 to 1980. Approximately 15 percent of instructional time should be spent on this period.

• Period 9: 1980 to present. Approximately 5 percent of instructional time should be spent on this period.

On the actual AP test that you will take:

• 5 percent of the exam will relate to issues concerning Period 1.

• 45 percent of the exam will relate to issues concerning Periods 2, 3, 4, and 5.

• 45 percent of the exam will relate to issues concerning Periods 6, 7, and 8.

• 5 percent of the exam will relate to issues concerning Period 9.

Many students are worried when their AP class doesn’t get to the present day. As you can see, only 5 percent of the test is on material after 1980; therefore, making it all the way to Barack Obama will not have a major impact on your score.

Structure of the AP U.S. History Exam

The AP U.S. History exam consists of two sections, each of which contains two parts. You’ll be given one hour and 45 minutes to complete Section I, which includes multiple-choice questions (Part A) and short-answer questions (Part B). You’ll have 90 minutes to complete Section II, which includes the document-based question (Part A) and the long-essay question (Part B). Here is the breakdown:

Section I

• Part A: 55 multiple-choice questions—55 minutes recommended—40% of the exam score.

• Part B: Four short-answer questions—50 minutes recommended—20% of the exam score. These questions will address one or more of the themes that have been developed throughout the course and will ask you to use historical thinking when you write about these themes.

Section II

• Part A: One document-based question (DBQ)—55 minutes recommended—25% of the exam score. In this section, you will be asked to analyze and use a number of primary-source documents as you construct a historical argument.

• Part B: One long-essay question—35 minutes recommended—15% of the exam score. You will be given a choice between two long-answer questions in this section. It will be critical to use historical thinking skills when writing your response.

This presents an overview. There will be more information about the different components of the exam later in this book.

Taking the AP U.S. History Exam

Registration and Fees

If you are enrolled in AP U.S. History, your teacher or guidance counselor is going to provide all of these details. However, you do not have to enroll in the AP course to take the AP exam. When in doubt, the best source of information is the College Board’s website: www.collegeboard.com.

There are also several other fees required if you want your scores rushed to you or if you wish to receive multiple score reports. Students who demonstrate financial need may receive a refund to help offset the cost of testing.

Night Before the Exam

Last minute cramming of massive amounts of material will not help you. It takes time for your brain to organize material. There is some value to a last-minute review of material. This may involve looking at the fast-review portions of the chapters or looking through the glossary. The night before the test should include a light review and various relaxing activities. A full night’s sleep is one of the best preparations for the test.

What to Bring to the Exam

Here are some suggestions:

• Several pencils and an eraser that does not leave smudges.

• Several black pens (for the essays).

• A watch so that you can monitor your time. The exam room may or may not have a clock on the wall. Make sure you turn off the beep that goes off on the hour.

• Your school code.

• Your driver’s license, Social Security number, or some other ID, in case there is a problem with your registration.

• Tissues.

• Something to drink—water is best.

• A quiet snack.

• Your quiet confidence that you are prepared.

What Not to Bring to the Exam

It’s a good idea to leave the following items at home or in the car:

• Your cell phone and/or other electronic devices.

• Books, a dictionary, study notes, flash cards, highlighting pens, correction fluid, a ruler, or any other office supplies.

• Portable music of any kind (although you will probably want to listen as soon as you leave the testing site!).

• Panic or fear. It’s natural to be nervous, but you can comfort yourself that you have used this book and that there is no need for fear on your exam.

Day of the Test

Once the test day has arrived, there is nothing further you can do. Do not worry about what you could have done differently. It is out of your hands, and your only job is to answer as many questions correctly as you possibly can. The calmer you are, the better your chances are of doing well.

Follow these simple commonsense tips:

• Allow plenty of time to get to the test site.

• Wear comfortable clothing.

• Eat a light breakfast and/or lunch.

• Think positive. Remind yourself that you are well prepared and that the test is an enjoyable challenge and a chance to share your knowledge.

• Be proud of yourself!

Preparing for the AP U.S. History Exam

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summary: The right preparation plan for you depends on your study habits and the amount of time you have before the test. This chapter provides some examples of plans you can use or adapt to your needs.

Key Ideas

Choose the study plan that is right for you.

Choose the study plan that is right for you.

Begin to prepare for the AP exam at the beginning of the school year. Developing historical analytical skills, evaluating themes in U.S. history, and studying important concepts take far more time and effort than by simply memorizing facts. The sooner you begin preparing for the test, the better.

Begin to prepare for the AP exam at the beginning of the school year. Developing historical analytical skills, evaluating themes in U.S. history, and studying important concepts take far more time and effort than by simply memorizing facts. The sooner you begin preparing for the test, the better.

Getting Started

You have made the decision to take AP U.S. History. Enjoy! You will be exposed to all of the fascinating stories that make up U.S. history. To be successful in this course, you will have to work much harder than you would in a “regular” high school U.S. history course. You will be required to read more, including reading and analyzing a wide variety of primary source documents throughout the year. In addition, you will be required to utilize historical thinking, to analyze history in a thematic way, and to be knowledgeable of specific concepts that help guide the study of American history. It cannot be stressed enough that the examination for this course that you will take in May is not a test that will simply measure what you “know” about U.S. history; instead, it is an examination that tests your ability to analyze major events, concepts, and themes in American history utilizing specific historical analytical skills.

Being able to utilize historical analytical skills, study history thematically, and develop conceptual thinking are not skills that develop overnight. In fact, it is difficult to develop these skills in the context of one specific course. If you are reading this before you are actually enrolled in an AP U.S. History course, you may want to take the most challenging history courses you can before you take AP U.S. History. Try to think conceptually in any history course that you take; it involves integrating historical facts into larger interpretive themes.

Creating a Study Plan

As has already been noted several times, preparing for this exam involves much more than just memorizing important dates, names, and events that are important in U.S. history. Developing historical analytical skills, evaluating themes in U.S. history, and studying important concepts take far more time and effort than by simply memorizing facts. Therefore, it is strongly suggested that you take a year-long approach to studying and preparing for the test.

However, for some students this is not possible. Therefore, some suggestions for students who have only one semester to prepare for the exam and students who have only six weeks to prepare for the exam are included. In the end, it is better to do some systematic preparation for the exam than to do none at all.

Study Groups

Many students who have gotten a 5 on the U.S. History exam reported that working in a study group was an important part of the successful preparation that they did for the test. In an ideal setting, three to five students get together, probably once a week, to review material that was covered in class the preceding week and to practice historical, thematic, and conceptual thinking. If at all possible, do this! A good suggestion is to have study groups set a specific time to meet every week and stick to that time. Without a regular meeting time, study groups usually meet fewer times during the year, often cancel meetings, and so on.

THREE PLANS FOR TEST PREPARATION

Plan A:

Yearlong Preparation for the AP U.S. History Exam

This is the plan we highly recommend. Besides doing all of the readings and assignments assigned by your teacher, also do the following activities. (Check off the activities as you complete them.)

IN THE FALL

______ Create a study group and determine a regular meeting time for that group.

______ Coordinate the materials in this manual with the curriculum of your AP U.S. History class.

______ Study the review chapters in Step 4 of this book that coincide with the material you are studying in class.

______ Begin to do outside reading on U.S. history topics (either topics of interest to you or topics that you know you need more background in).

______ In your study group, emphasize historical analysis and thematic and conceptual thinking.

FROM DECEMBER TO MARCH

______ Continue to meet with your study group and emphasize historical analysis and thematic and conceptual thinking.

______ Continue to study the review chapters in Step 4 of this book that coincide with the material you are studying in class.

______ Take the diagnostic test in Step 2 of this book to see what the test will be like and assess your strengths and weaknesses.

______ Learn the strategies discussed in Step 3 of this book. Practice applying them as you study and review for the AP U.S. History exam.

______ Carefully study the format and approach to document-based questions (DBQs). You will probably have one on your midterm exam in class.

______ Using the eras of U.S. history you have studied in class, create your own DBQ for two of the units and try to answer it.

______ Intensify your outside reading of U.S. history topics.

______ Take two U.S. history textbooks and compare and contrast their handling of three events of U.S. history. What do these results tell you?

DURING APRIL AND MAY

______ Continue to meet with your study group and emphasize historical analysis and thematic and conceptual thinking. Many study groups meet at additional times in the weeks leading up to the test.

______ Continue to study the review chapters in Step 4 of this book that coincide with the material you are studying in class.

______ Practice creating and answering multiple-choice and short-answer questions in your study group.

______ Develop and review worksheets of essential historical content with your study group.

______ Highlight material in your textbook (and in this manual) that you may not understand, and ask your teacher about it.

______ Write two or three essays as they would appear on the exam under timed questions and have a member of your study group (or a classmate) evaluate them.

______ Take the practice tests provided in Step 5 of this book. Set a timer and practice pacing yourself.

You are well prepared for the test. Go get it!

Plan B:

One-Semester Preparation for the AP U.S. History Exam

Besides doing all of the readings and assignments assigned by your teacher, you should do the following activities. (Check off the activities as you complete them.)

FROM JANUARY TO MARCH

______ Establish a study group of other students preparing in the same way that you are. In your study group you should review essential factual knowledge, but also analyze the essential themes and concepts in the course.

______ Study the review chapters in Step 4 of this book that coincide with the material you have studied or are studying in class.

______ Take the diagnostic test in Step 2 of this book to familiarize yourself with the test and assess your strengths and weaknesses.

______ Learn the strategies discussed in Step 3 of this book. Practice applying them as you study and review for the AP U.S. History exam.

______ Write two or three document-based and sample multiple-choice questions.

______ Read at least one outside source (historical essay or book) on a topic that you are studying in class.

______ In your study group, practice creating and answering short-answer and multiple-choice questions.

DURING APRIL AND MAY

______ Continue to meet with your study group, and review essential factual knowledge and essential themes and concepts of the course you have taken or are currently taking. Some study groups increase the amount of time that they meet together in the weeks right before the test.

______ Study the review chapters in Step 4 of this book that coincide with the material you have studied or are presently studying in class. Focus on weak areas you identified in the diagnostic test of Step 2 of this book.

______ Practice creating and answering sample essays with your study group.

______ Develop and review worksheets of essential historical content with your study group.

______ Ask your teacher to clarify things in your textbook or in this manual that you do not completely understand. If you have nagging questions about some specific historical details, get the answers to them!

______ Take the practice tests provided in Step 5 of this book. Set a timer and practice pacing yourself.

Plan C:

Four- to Six-Week Preparation for the AP U.S. History Exam

Besides doing all of the reading and assignments assigned by your teacher, do the following activities. (Check off the activities as you complete them.)

IN APRIL

______ Take the diagnostic test in Step 2 of this book to familiarize yourself with the test and assess your strengths and weaknesses.

______ Study the review chapters in Step 4 of this book that coincide with any weak areas you identified from the diagnostic exam.

______ Learn the strategies discussed in Step 3 of this book. Practice applying them as you study and review for the AP U.S. History exam.

______ Write one sample document-based question (DBQ) as modeled by samples in this manual.

______ Carefully review the sections of this manual that outline the essential content of each historical period.

______ If possible, create or join a study group with other students to help prepare for the exam.

IN MAY

______ Many teachers organize study sessions right before the actual exam. Go to them!

______ With your study group or individually, review essential content from the course and major concepts of each unit.

______ Complete another sample DBQ essay and analyze your results.

______ Review the glossary of this manual another time to help review essential content.

______ Be certain of the format of the test and the types of questions that will be asked.

______ Take the practice tests provided in Step 5 of this book. Set a timer and practice pacing yourself.

Take a Diagnostic Exam

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summary: In the following pages, you will find a diagnostic exam whose content and structure closely matches the “real” AP U.S. History exam. Use this test to familiarize yourself with the actual test and to assess your strengths and weaknesses.

How to Use the Diagnostic Exam

Section I of the AP U.S. History exam contains a multiple-choice section and a short-answer section. The test is now set:

Section II contains the document-based question (DBQ) and an essay question—you will need to pick one question to answer out of the two questions you are given.

55 minutes for 55 multiple-choice questions

50 minutes for 4 short-answer questions

55 minutes for one document-based question

35 minutes for one long essay question

The purpose of this chapter is to allow you to familiarize yourself with the test and to assess your test readiness in terms of both the skills and the content understanding needed. Try to take this test under testlike conditions; in other words, time yourself and do the test—or at least each section of the test—uninterrupted. Note that in Chapter 5 you will find strategies for each type of question that will allow you to more effectively and efficiently tackle the questions.

When to Use the Diagnostic Exam

This diagnostic test can be helpful to you regardless of whether you are following Plan A, B, or C. Those who chose Plan A should study this exam early in the year so that you will thoroughly understand the format of the test. Look for the types of multiple-choice and short-answer questions early and carefully study the format of the essay questions. Go back and look at this exam throughout the year: Many successful test-takers maintain that knowing how to tackle the questions that will be asked on any exam is just as important as knowledge of the subject matter.

Plan B students (who are using one semester to prepare) should also analyze the format of the exam. Plan B folks: as you begin using this book you might also want to actually answer the multiple-choice and short-answer questions dealing with content you have already studied in class and answer the document-based question and the free-response question and evaluate your results. This will help you analyze the success of your previous preparation for the test.

Plan C students should take this diagnostic exam as soon as they begin working with this manual to analyze the success of their previous preparation for the actual exam.

Conclusion (After the Exam)

After you have studied or taken the diagnostic exam, you will continue to Step 3 of your 5 Steps to a 5. Chapter 5 will provide you with tips and strategies for answering all of the types of questions that you found on the diagnostic exam.

Don’t be discouraged and if you answered a lot of questions on the diagnostic exam incorrectly. At this point, the main thing is that you get a feel for the types of questions that you will encounter on the real AP U.S. History exam.

AP U.S. HISTORY DIAGNOSTIC EXAM

Answer Sheet for Multiple-Choice Questions

AP U.S. HISTORY DIAGNOSTIC EXAM

Section I

Time: 1 hour, 45 minutes

Part A (Multiple Choice)

Part A recommended time: 55 minutes

Directions: Each of the following questions refers to a historical source. These questions will test your knowledge about the historical source and require you to make use of your historical analytical skills and your familiarity with historical themes. For each question select the best response and fill in the corresponding oval on your answer sheet.

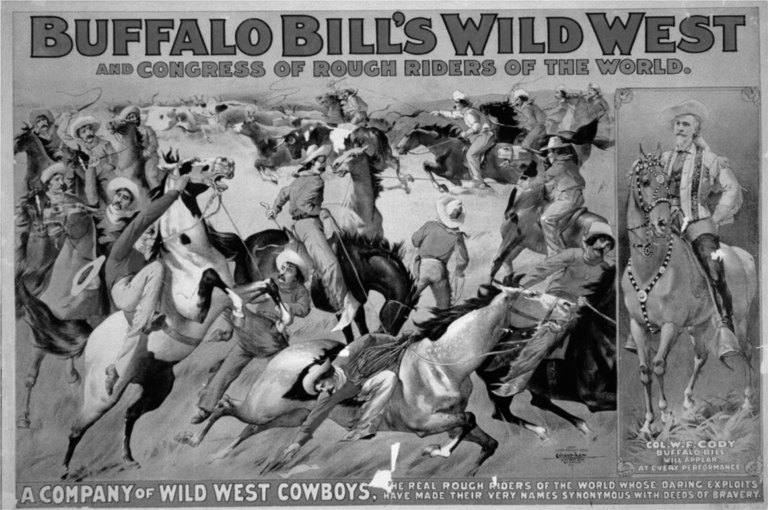

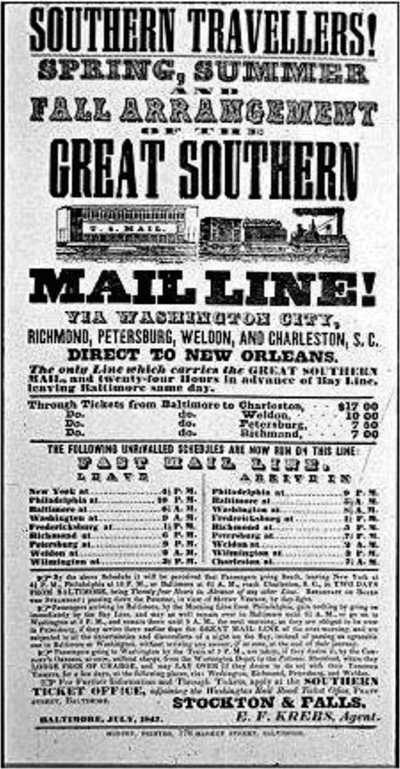

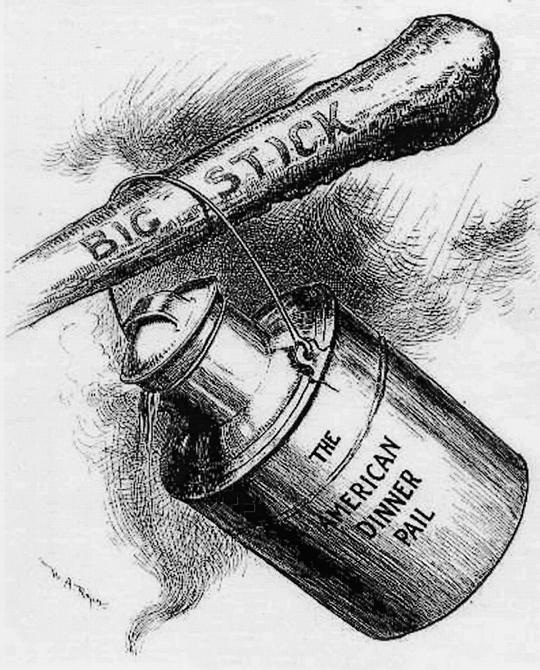

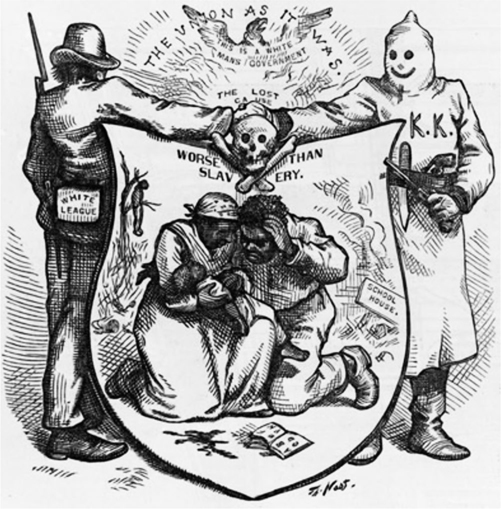

Questions 1–4 refer to the following cartoon.

Political cartoon from 1807

1. This cartoon criticizes which policy of President Thomas Jefferson?

A. The Louisiana purchase

B. The Embargo Act

C. The War with Tripoli

D. Reductions in government spending

2. Jefferson was responding to what situation?

A. British interference with American shipping and trade

B. British support for Indians in the West

C. Aggressive actions by the French Emperor Napoleon

D. Electoral losses to domestic opponents

3. Which of the following reflects how many Americans responded to Jefferson’s policy?

A. Emigrating to other countries

B. Advocating military involvement in the Napoleonic Wars

C. Engaging in illicit trade with foreign countries

D. Moving to the Western frontier

4. Which of the following most closely resembles Jefferson’s policy?

A. The Open Door in China

B. The Good Neighbor Policy with South America

C. Manifest Destiny of the 1840s

D. Neutrality Laws of the 1930s

Questions 5–8 refer to the following quotation.

Yes, let us pray for the salvation of all those who live in that totalitarian darkness—pray that they will discover the joy of knowing God. But until they do, let us be aware that while they preach the supremacy of the State, declare its omnipotence over individual man, and predict its eventual domination of all peoples on the earth, they are the focus of evil in the modern world.… But if history teaches anything, it teaches that simpleminded appeasement or wishful thinking about our adversaries is folly. It means the betrayal of our past, the squandering of our freedom. So, I urge you to speak out against those who would place the United States in a position of military and moral inferiority.… So, in your discussions of the nuclear freeze proposals, I urge you to beware the temptation of pride—the temptation of blithely … declaring yourselves above it all and label both sides equally at fault, to ignore the facts of history and the aggressive impulses of an evil empire, to simply call the arms race a giant misunderstanding and thereby remove yourself from the struggle between right and wrong and good and evil.

—Ronald Reagan, Address to the National Association of Evangelicals, March 8, 1983

5. The sentiments in the passage above most directly reflect which of the following?

A. A religious revival in the 1980s

B. An intensification of the cold war in the early 1980s

C. A desire to limit the size of government

D. A distrust of the American military

6. Which of the following would have been most likely to approve the sentiments expressed in the passage?

A. An antinuclear activist

B. An atheist

C. A Democrat

D. A Republican

7. The sentiments expressed in the passage are most closely linked to which of the following policies?

A. Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI)

B. Business deregulation

C. Encouraging prayer in the public schools

D. Military cutbacks

8. The sentiments in the passage best reflect which long-standing concern of American presidents?

A. Support for civil rights

B. Promoting the separation of church and state

C. Containment of communism

D. Expanding the welfare state

Questions 9–12 refer to the following quotation.

They were smart and sophisticated, with an air of independence about them, and so casual about their looks and manners as to be almost slapdash. I don’t know if I realized as soon as I began seeing them that they represented the wave of the future, but I do know I was drawn to them. I shared their restlessness, understood their determination to free themselves of the Victorian shackles of the pre-World War I era and find out for themselves what life was all about.

—Colleen Moore, movie star, writing about the 1920s

9. In this passage, Moore is writing about which of the following?

A. The Ku Klux Klan

B. Prohibitionists

C. Flappers

D. The Model T

10. Many young women of the 1920s expressed their freedom through which of the following?

A. Political activism

B. “Mannish” haircuts, new clothing styles, and cosmetics

C. Living amongst the poor in settlement houses

D. Rejection of marriage and child-rearing

11. The new freedoms for women in the 1920s were supported by which of the following?

A. Widespread economic prosperity

B. Growth in fundamentalist Christianity

C. A massive movement of women into political offices

D. Moral reforms like the temperance movement

12. The passage by Moore most directly reflects which of the following continuities in United States history?

A. Concerns about economic inequality

B. Efforts to expand civil rights

C. Worries about political radicalism

D. Concerns for individual liberty and self-expression

Questions 13–16 refer to the following quotation.

I am for doing good to the poor, but … I think the best way of doing good to the poor, is not making them easy in poverty, but leading or driving them out of it. I observed … that the more public provisions were made for the poor, the less they provided for themselves, and of course became poorer. And, on the contrary, the less was done for them, the more they did for themselves, and became richer.

—Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography

13. In this passage, Franklin takes a position similar to which of the following?

A. Advocates of a market-driven economy like Adam Smith

B. Supporters of the First Great Awakening

C. Opponents of British rule in America

D. Believers in an extensive social welfare system

14. The idea that Franklin expresses in this passage most directly reflects which of the following continuities in U.S. history?

A. Concern about a religious foundation for society

B. Belief in individual self-reliance

C. A distrust of politicians

D. A desire to expand Social Security

15. Which of the following helped Franklin justify his position?

A. Strong class distinctions in colonial America

B. British efforts to tax Americans

C. A decline in religious beliefs

D. Social mobility in colonial America

16. Which of the following presidents would be most likely to share Franklin’s position?

A. Barack Obama

B. Lyndon Baines Johnson

C. Calvin Coolidge

D. Franklin D. Roosevelt

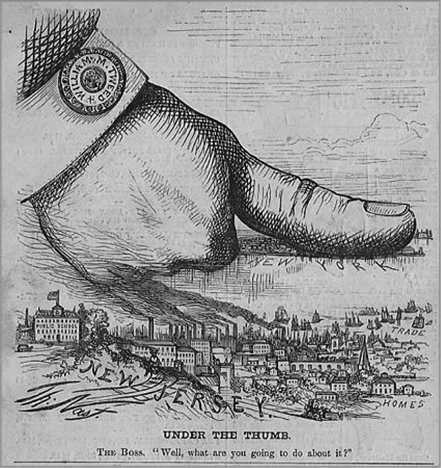

Questions 17–20 refer to the following cartoon.

Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, June 10, 1871

17. Which of the following best expresses Nast’s perspective in this cartoon?

A. New York City is benefiting from the leadership of Tammany Hall boss William M. Tweed

B. New Jersey is unfairly exploiting New York City

C. The federal government is oppressing New York City

D. Tammany Hall boss William M. Tweed wields too much power in New York City

18. Urban political machines like Tammany Hall derived most of their support from which of the following?

A. Immigrants and lower-class voters

B. The wealthier classes of society

C. Patronage from the federal government

D. Rural voters from outside the city

19. Urban political machines endured for many years because they provided which of the following?

A. Honest and efficient government

B. Help and services for the poor

C. Rights and privileges unavailable outside the city

D. Opposition to the encroachments of the federal government

20. Nast’s journalistic perspective can best be compared to which of the following?

A. Progressive muckrakers exposing the business practices of the Standard Oil Company

B. Yellow journalists during the period of the Spanish-American War

C. Reporters investigating President Richard M. Nixon during the Watergate scandal

D. Newspaper coverage of World War II

Questions 21–24 refer to the following quotation.

At last they brought him [John Smith] to Werowocomoco, where was Powhatan, their emperor. Here more than two hundred of those grim courtiers stood wondering at him, as he had been a monster; till Powhatan and his train had put themselves in their greatest braveries. Before a fire upon a seat like a bedstead, he sat covered with a great robe, made of raccoon skins, and all the tails hanging by. On the other hand did sit a young wench of sixteen or eighteen years, and along on each side of the house, two rows of men, and behind them as many women, with all their heads and shoulders painted red, many of their heads bedecked with the white down of birds, but every one with something, and a great chain of white beads about their necks. At his entrance before the king, all the people gave a great shout.… Having feasted him after their best barbarous manner they could, a long consultation was held, but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan; then as many as could laid hands on him, dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs to beat out his brains, Pocahontas, the king’s dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save his from death; whereat the emperor was contented he should live to make him hatchets, and her bells, beads, and copper; for they thought him as well of all occupations as themselves. For the king himself will make his own robes, shoes, bows, arrows, pots; plant, hunt, or do anything so well as the rest.

—John Smith, The General Historie of Virginia, 1624

21. Which of the following best describes the perspective of Captain John Smith?

A. Powhatan and his followers were a backward people.

B. Europeans unfairly looked down on Indians.

C. Indians lacked the vices of the more technologically advanced Europeans.

D. Indian women were the dominant force in their society.

22. Smith’s account makes clear which of the following?

A. The people of Powhatan’s Confederacy were divided by strong class distinctions.

B. Powhatan’s people made important decisions by consensus.

C. Powhatan enjoyed the same sorts of power as a European king.

D. Powhatan’s people lived in poverty.

23. Smith’s story best illustrates which of the following?

A. Indians were unusually cruel.

B. Europeans were usually deceitful in dealing with Indians.

C. The English were foolish to venture into the American wilderness.

D. Indian-European relations often suffered from misunderstanding and suspicion.

24. In the context of this story, Pocahontas can best be compared to which of the following women?

A. Susan B. Anthony

B. Sally Ride

C. Jane Addams

D. Amelia Earhart

Questions 25–28 refer to the following quotation.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

—Martin Luther King, Jr., “I Have a Dream” speech, Lincoln Memorial, August 28, 1963

25. Martin Luther King, Jr., in this passage is calling for which of the following?

A. Economic justice for the poor

B. Renewed commitment to the cold war struggle against communism

C. Equal rights for African Americans

D. Special privileges for African Americans

26. In this passage, King points out which of the following?

A. A contradiction between American ideals and American practice

B. A need to create new American ideals

C. The superiority of African American values

D. The futility of hoping for change

27. At the time of King’s speech, which of the following would be likely to oppose King’s message?

A. A Midwestern Republican Senator

B. A Southern Democratic Senator

C. A Northern liberal

D. A member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

28. In this passage, King is addressing which continuity in U.S. history?

A. The struggle for greater economic opportunity

B. A fear of sectionalism in the United States

C. Concerns about moral decline

D. The struggle for individual liberty

Questions 29–32 refer to the following cartoon.

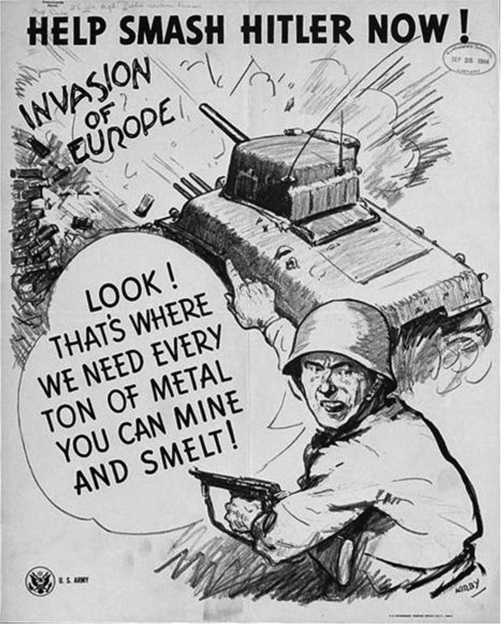

War Department cartoon, 1943

Credit: U.S. Army

29. The message of the cartoon can be best described by which of the following?

A. The invasion of Europe is endangered by inferior weapons.

B. The war is being lost.

C. Too many American supplies have been given to allied nations.

D. Civilians play a vital role in the war effort.

30. Viewing this cartoon would encourage Americans to do which of the following?

A. Avoid the wasteful use of metal products

B. Plant a victory garden

C. Volunteer for military service

D. Build fewer ships and construct more tanks

31. This cartoon most directly refers to which aspect of the American war effort during World War II?

A. American efforts to launch a second front in Europe as early as possible

B. Military operations in the Mediterranean in 1942 and 1943

C. American industrial production

D. Efforts to create new and improved weapons systems

32. The message of the cartoon for Americans can best be compared to which of the following?

A. The environmental movement of the 1970s

B. The boycotts of British goods in the 1760s and 1770s

C. Abolitionism in the nineteenth century

D. Consumerism in the 1950s

Questions 33–36 refer to the following quotation.

That whereas your poor and humble Petition(er) being condemned to die, do humbly beg of you to take it into your Judicious and pious considerations that your poor and humble petitioner knowing my own innocence Blessed be the Lord for it and seeing plainly the wiles and subtlety of my accusers by my self can not but Judge charitably of Others that are going the same way of my self if the Lord steps not mightily in I was confined a whole month upon the same account that I am condemned now for and then cleared by the afflicted persons as some of your honors know and in two days time I was cried out upon by them and have been confined and now am condemned to die the Lord above knows my innocence then and likewise does now at the great day will be known to men and Angels I petition your honors not for my own life for I know I must die and my appointed time is set but the Lord he knows it is that if be possible no more Innocent blood may be shed which undoubtedly cannot be avoided In the way and course you go in I Question not but your honors does to the utmost of your Powers in the discovery and detecting of witchcraft and witches and would not be guilty of Innocent blood but for the world but by my own innocence I know you are in the wrong way the Lord in his infinite mercy direct you in this great work if it be his blessed will that no more innocent blood be shed.

—Mary Easty, petition to her judges, Salem, Massachusetts, 1692

33. Mary Easty in this passage is asking her judges to do which of the following?

A. Stop condemning innocent persons to death for witchcraft

B. Redouble their efforts to find the real witches in Salem

C. Separate church from state in their deliberations

D. Stop their oppression of women

34. Most historians believe that the Salem Witch Trials were the result of which of the following?

A. The activities of a coven of witches in Salem

B. Social tensions in Salem

C. English efforts to enforce religious conformity in Massachusetts

D. The ideas of the English political philosopher John Locke

35. The religious convictions of Mary Easty and the rest of Salem were shaped by which of the following?

A. Roman Catholicism

B. Anglicanism

C. Quakerism

D. Puritanism

36. Writers and intellectuals have often compared the Salem Witch Trials to which of the following?

A. The mistreatment of slaves in the South

B. Anti-immigrant rioting in the nineteenth century

C. Government actions in the Red Scares of the twentieth century

D. The suppression of strikers in the late nineteenth century

Questions 37–40 refer to the following quotation.

Companions in Arms!! These remains which we have the honor of carrying on our shoulders are those of the valiant heroes who died in the Alamo. Yes, my friends, they preferred to die a thousand times rather than submit themselves to the tyrant’s yoke. What a brilliant example! Deserving of being noted in the pages of history. The spirit of liberty appears to be looking out from its elevated throne with its pleasing mien and pointing to us saying: “These are your brothers, Travis, Bowie, Crockett, and others whose valor places them in the rank of my heroes.” Yes soldiers and fellow citizens, these are the worthy beings who, by the twists of fate, during the present campaign delivered their bodies to the ferocity of their enemies; who barbarously treated as beasts, were bound by their feet and dragged to this spot, where they were reduced to ashes. The venerable remains of our worthy companions as witnesses, I invite you to declare to the entire world, “Texas shall be free and independent or we shall perish in glorious combat.”

—Colonel Juan N. Seguin, Alamo Defenders’ Burial Oration, Columbia Telegraph and Texas Register, April 4, 1837

37. Colonel Juan N. Seguin honored the memory of the defenders of the Alamo because

A. they fought to the death for their cause

B. they defeated an invading Mexican army

C. they saved New Orleans from the British

D. they saved San Antonio from a large war band of Comanche

38. Colonel Seguin’s oration makes it clear that

A. he thought the defense of the Alamo was a strategic mistake

B. many Tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent) favored Texan independence

C. he thought the United States was imposing a tyranny on Texas

D. he opposed the movement of American settlers into Texas

39. The defenders of the Alamo gave their lives for what continuity in American history?

A. The quest for racial justice

B. The desire for political liberty

C. The search for social security

D. Opposition to gun control

40. A dispute over the boundary of Texas led to which of the following conflicts?

A. The War of Jenkins’ Ear

B. The Quasi-War with France

C. The Spanish–American War

D. The Mexican War

Questions 41–44 refer to the following quotation.

When we stormed the Pentagon, my wife and I we leaped over this fence, see. We were really stoned, I mean I was on acid flying away, which of course is an antirevolutionary drug you know, you can’t do a thing on it. I’ve been on acid ever since I came to Chicago. It’s in the form of honey. We got a lab guy doin’ his thing. I think he might have got assassinated, I ain’t seen him today. Well, so we jumped this here fence, see, we were sneaking through the woods and people were out to get the Pentagon. We had this flag, it said NOW with a big wing on it, I don’t know. The right-wingers said there was definitely evidence of Communist conspiracy ’cause of that flag.… So we had Uncle Sam hats on, you know, and we jumped over the fence and we’re surrounded by marshals, you know, just closin’ us in, about 30 marshals around us. And I plant the . . . flag and I said, “I claim this land in the name of free America. We are Mr. and Mrs. America. Mrs. America’s pregnant.” And we sit down and they’re goin’ . . . crazy. I mean we got arrested and unarrested like six or seven times.

—Abbie Hoffman, Yippie Workshop Speech, 1968

41. Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies were protesting which of the following?

A. McCarthyism

B. The Great Society

C. Legal acid

D. The Vietnam War

42. Which of the following most directly influenced the ideas of Hoffman and the Yippies?

A. Muckrakers

B. The New Deal

C. The New Left

D. The New Conservatism

43. Which of the following most directly influenced the tactics of Hoffman and the Yippies?

A. The Civil Rights Movement

B. The House Un-American Activities Committee

C. The Tea Party Movement

D. The Social Gospel

44. The counterculture of the 1960s sought which of the following?

A. Economic security for the Baby Boom generation

B. Political and military security against the threat of Communism

C. Greater freedom for personal self-expression

D. A return to traditional religious and family values

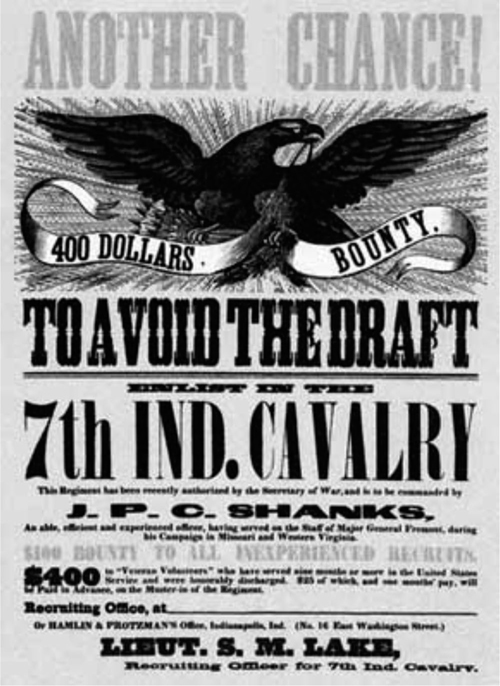

Questions 45–48 refer to the following image.

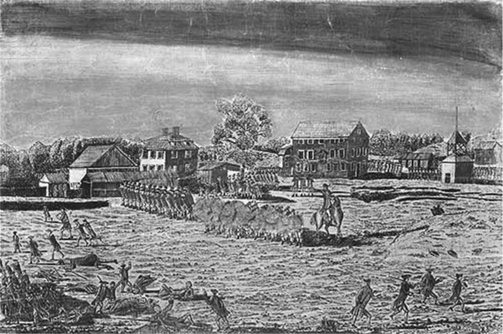

Amos Doolittle, “The Battle of Lexington,” 1775

45. The British decision to fire on American militiamen at Lexington, Massachusetts, on April 19, 1775, led to which of the following?

A. A controversial court case

B. A series of uprisings against the British government across the colonies

C. A collapse in the support for the Sons of Liberty

D. An invasion by the French in Canada

46. British military commanders always assumed that they would benefit from which of the following?

A. Command of the sea

B. The support of the other European powers

C. Superior air power

D. The support of a majority of Americans for Parliament’s legislation

47. When the Americans rebelled against Great Britain, they benefitted from which of the following?

A. The enormous industrial productivity of the United States

B. Weapons that were technologically superior to those of the British

C. The support of most Native American peoples

D. The great geographical extent of the country

48. Militiamen played a key role during the American Revolutionary War by

A. repeatedly routing British Regulars in battle

B. waging a spectacular campaign of sabotage and commando raids

C. controlling populations not under the direct supervision of the British Army

D. buying out the contracts of Britain’s Hessian mercenaries

Questions 49–52 refer to the following quotation.

I arrived at Wichita the 28th, the raid was postponed until the 29th. I took hatchets with me and we also supplied ourselves with rocks, meeting at the M. E. church, where the W. C. T. U. Convention was being held. I announced to them what we intended doing and asked them to join us. Sister Lucy Wilhoite, Myra McHenry, Miss Lydia Muntz, and Miss Blanch Boies, started for Mahan’s wholesale liquor store. Three men were on the watch for us, we asked to go in to hold gospel services as was our intention before destroying this den of vice, for we wanted God to save their souls, and to give us ability and opportunity to destroy this soul damning business. They refused to let us come near the door. I said, “Women, we will have to use our hatchets,” with this I threw a rock through the front, then we were all seized, and a call for the police was made. There was of course, a big crowd. Mrs. Myra McHenry was in the hands of a ruffian who shook her almost to pieces. One raised a piece of a gas pipe to strike her, but was prevented from doing so. We were hustled into the hoodlum wagon, and driven through the streets amid the yell, execrations and grimaces of the liquor element.

—Carry A. Nation, The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation, Written by Herself, 1905

49. For which of the following causes was Carry A. Nation famous as an activist?

A. Temperance

B. Women’s suffrage

C. Trust busting

D. Muckraking

50. Nation can be compared most directly to which of the following?

A. Tecumseh

B. Abraham Lincoln

C. Rosa Parks

D. Hillary Clinton

51. Nation’s cause would attain a great victory with the enactment of

A. the Nineteenth Amendment, giving women the vote

B. the Sherman Antitrust Ac

C. the Social Security Act

D. Prohibition

52. The major event that helped pave the way for the triumph of Nation’s cause was

A. the assassination of William McKinley

B. World War I

C. The Great Depression

D. World War II

Questions 53–55 refer to the following quotation.