Crash Course for the New GRE, 4th Edition (2011)

Part II. Ten Steps to Scoring Higher on the GRE

Step 2. Slow Down for Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension is an open-book test. The answers are in the passage. With unlimited time, in theory, you should never get a reading comprehension question wrong. There are three ways you can give yourself more time on reading comprehension.

· The first is to get so good at text completions and sentence equivalence that you have plenty of time left over for reading comp, where time equals points.

· The second way to pick up time is to pick your battles. Take on fewer passages, do fewer questions, but get more right. Rushing through reading comp guarantees wrong answers. Slow down and make sure that the time you spend yields points.

· The last way to give yourself more time on reading comp is to be smart about where you spend your time. There is a lot of information in the passages, but you will be tested on only a tiny portion of that information. A smart and efficient strategy for working with the passages will pay dividends in the form of more time and less stress.

There are three basic components of reading comprehension:

The Passages

ETS does not write the passages. They license the rights to a few books at a time and then mine those books for reading comp passages, text completion passages, and sentence equivalence sentences. Because of this, it is not uncommon to see the same subjects pop up more than once on a given test. Most authors strive for clarity. Too much clarity, however, is a problem if you need to write a difficult test. So ETS will manipulate the passages to make them harder to work with. To do this, they start with a 1,200-word passage (passages could range in length from 250 words to 1,000 words) and then will shrink it down to about 1,000 words for a long passage. To shrink it down, they get rid of explanations, definitions, clear subject-verb-object sentences, and anything else that makes good, clear writing good and clear. They keep in extraneous facts you will never need to know, long twisting sentences with lots changes in direction (it’s not at all uncommon for the entire first paragraph of a passage to be one long sentence), poorly defined technical terms, and anything else that will make it hard to absorb all of the information in a given passage after a single reading. The passages are designed to be dense and difficult to read.

The Questions

You’ll notice that most of the questions aren’t really questions at all. They’re really incomplete sentences. Before you even start looking for an answer, you have to find the question in the question!

The Answer Choices

There are a number of different games that ETS loves to play with the answer choices. First they will give you an answer choice that is clearly supported by the passage but does not answer the question and so is wrong. Or, they will give you an answer choice that does answer the question, but they’ll twist it just slightly so that it is wrong. Or they will give you an answer that perfectly answers the question but that isn’t supported by information in the passage and is therefore wrong. The answer choices are carefully designed to mislead. Unless you have a crystal clear idea of what you are looking for, some of the wrong answer choices can be mighty tempting.

The number one golden rule of reading comprehension is this: If you cannot put your finger on a word, phrase, or sentence in the passage that proves your answer choice, you cannot pick it.

For every single question, you must always go back to the passage and find proof. Always. No exceptions. The minute you stop reading, you start forgetting, and no one can remember all of the information in these passages anyway. ETS will exploit your memory of the passage with tempting but wrong answer choices. When you answer a question from memory, you make their job even easier.

As long as you have to go back to the passage for proof for every question anyway, the obvious question, then, is how much of the passage should you read in the first place?

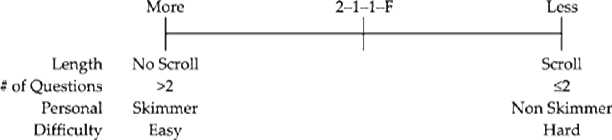

This depends upon four criteria:

(Click here to view a larger image.)

You can always read more of a passage if you have to, but you never want to read more than you have to.

To start a passage, you need to know three things: the main idea, the structure, and the tone. Let’s say a passage is about a problem scientists are trying to solve. To get started, all you need to know is that there is a question, scientists are trying to answer it, but they haven’t yet. The rest is just details. You may eventually need to know these details or you may not, but you can look for them on a question-by-question basis, as needed.

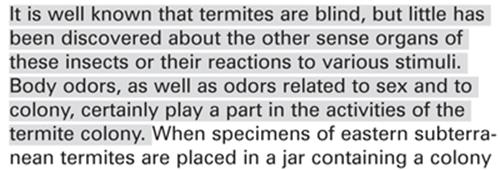

A good place to start reading for the main idea without getting bogged down in the details is 2-1-1-F. This means that you read the first two sentences of a passage, the first sentence of each additional paragraph, and the final sentence of the passage. Generally, this will be sufficient to give you the main idea of the passage. If it is not, no problem; just read a bit more. Remember: You are going to go back to the passage to find proof for every problem, no matter what, anyway. You do not need comprehensive knowledge of the whole passage at this point.

Here’s a sample passage with 2-1-1-F highlighted:

What’s the passage about?

Termites and how they perceive the world (they’re blind).

Do we know the answer?

No. But we have some clues. Something about order, the chorodontal system, and vibrations.

Does the author take a position?

Nope, purely a description of a scientific exploration.

How long did it take you to read those six sentences? Less than a minute, right? You now know the main idea of the passage, roughly what each paragraph is about, and the tone. Best of all, you haven’t spent a lot of time, and you haven’t been distracted by lots of useless and confusing details.

The Questions

When it comes to answering specific questions, there is a basic five step process:

Step 1. Read the question—You can answer questions in any order you like. Some questions, like a main idea question, you are already equipped to answer. Other questions may ask you to prove four or five answer choices, and these you might want to save until you’ve spent more time with the passage.

Step 2. Make the question into a question—In order to find an answer, you must have a question. Most questions ask you either “what was stated in the passage” or “why was it said?” The easiest way to make the question into a question, therefore, is to simply start with a question word. Most of the time, “what” or “why” will do the trick. Note: In this step you are also engaging in the question in a qualitative way. This is important because your brain is going to get tired, and when it does, it is all too easy to skim a question and have no idea what it’s really asking.

Step 3. Find proof—Always go back to the passage and find proof. If they highlight a portion of the passage, start reading four or five lines before the highlighted section and read until four or five lines after. You always want to look at things in context. If they don’t highlight the text, use a lead word (any word that will be easy to skim for in the passage: names, dates, technical terms, anything with a capital letter—all make good lead words), and then read five lines up and five lines down.

Step 4. Answer the question in your own words—Remember that the answer choices are designed to tempt and mislead you. They are very good at it. If you don’t have a clear sense of what you’re looking for, they’ll serve up some mighty tempting, but wrong, answer choices. If you do know what you’re looking for, wrong answers will look wrong and right ones will look right.

Before we get to step five, let’s look at a few questions:

The author’s primary concern in the passage is to

1. Read the question: Done

2. What is this question asking? What is the main idea of the passage: Termites and how they perceive the world (they’re blind).

3. Find proof: Go back to 2-1-1-F. Do we need more? Nope.

4. Answer the question in your own words: Investigate ways the termite perceives the world if it’s not through the eyes.

Now you’re equipped to handle the answer choices (answer choices to follow).

According to the passage, a termite’s jaw can be important in all of the following EXCEPT

1. Read the question: Done. This question asks us to chase down five pieces of information about the termite’s jaw. That’s a lot of work. We might want to leave this one for the end.

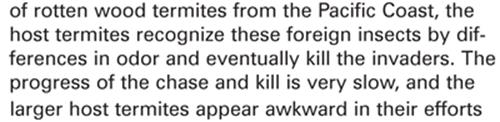

It can be inferred from the passage that dealated eastern termites that have survived a week in a rotten wood termite colony are no longer attacked because they

1. Read the question: Done

2. Make the question into a question: Why are “dealated termites” that survive a week, no longer attacked?

3. Find proof: “Dealated termites” will make a good lead word. Skim the passage until you find it, and then read five lines up and five lines down.

4. Answer the question in your own words: You’ve got to read quite a bit of the first paragraph, and most of the second paragraph to figure this one out. (Good thing we didn’t waste time reading all of this on the first pass then we’d end up reading it twice.) It seems that after a week, the eastern termites no longer smell bad.

The Answer Choices:

Step 5. Use Process of Elimination—Do not look for right answers. You will always be able to find a reason why an answer could be right. Look for the wrong ones. If you find a reason why an answer is wrong, you can eliminate it. If you can’t find a reason it’s wrong, that’s a good sign that it’s right. Always stick to things that you can objectively prove with the passage. There are some common reasons answer choices are wrong:

Extremes—Beware of extreme language. Extreme language is too easy to argue with. ETS prefers to play it safe, so they phrase correct answers in nice, wishy-washy language that is difficult to argue with.

Scope—If it’s not in the passage, you can’t pick. Watch out for answer choices that include things never mentioned in the passage. On main idea questions, watch out for answer choices that are too specific.

Common Sense—Not all answer choices make sense. Just because it’s on the test, doesn’t mean that you can’t laugh at it—and eliminate it.

Let’s try a few out, but first get your scratch paper out and get ready to start marking up answer choices.

The author’s primary concern in the passage is to

![]() show how little is known of certain organ systems in insects

show how little is known of certain organ systems in insects

![]() describe the termite’s method of overcoming blindness

describe the termite’s method of overcoming blindness

![]() provide an overview of some termite sensory organs

provide an overview of some termite sensory organs

![]() relate the termite’s sensory perceptions to man’s

relate the termite’s sensory perceptions to man’s

![]() describe the termite’s aggressive behavior

describe the termite’s aggressive behavior

What does the question ask? What is the main idea of the passage: Investigate ways the termite perceives the world if it’s not through the eyes.

Answer: Investigate ways the termite perceives the world if it’s not through the eyes.

(A) If the passage is about termites, then the answer to a main idea question had better mention termites. Cross off (A).

(B) Hmmm. Possibly, but if the termites don’t know they’re blind, they’re not overcoming anything. Give it the “maybe.”

(C) This is possible. Give it a check.

(D) Whoa! Even if this was mentioned, it’s certainly not the main idea. Cross off (D).

(E) Whoa again! Might be true, but what about odor, and the choronodtal system, and everything else? Get rid of it.

Now check your scratch paper. You’ve got a “maybe” and a “check.” If you’ve got one that works, go with it. You’re done.

It can be inferred from the passage that dealated eastern termites that have survived a week in a rotten wood termite colony are no longer attacked because they

![]() have come to resemble the rotten wood termites in most ways

have come to resemble the rotten wood termites in most ways

![]() no longer have an odor provocative to the rotten wood termites

no longer have an odor provocative to the rotten wood termites

![]() no longer pose a threat to the host colony

no longer pose a threat to the host colony

![]() have learned to resonate at the same frequency as the host group

have learned to resonate at the same frequency as the host group

![]() have changed the pattern in which they use their mandibles

have changed the pattern in which they use their mandibles

What does the question ask? Why are “dealated termites” that survive a week, no longer attacked?

What’s the answer in your own words? Because after a week the eastern termites no longer smell bad.

(A) This is a little extreme. They change shape? Change size? Got a hair cut? Cross it off.

(B) Talks about smell. Give it a check.

(C) Do we know this? Can we prove it? They might still be a threat. Cross it off.

(D) Resonate, huh? Cross it off.

(E) Mandibles, huh? Cross it off.

The answer is (B).

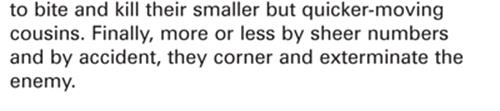

According to the passage, a termite’s jaw can be important in all of the following EXCEPT

![]() aggression against intruders of other termite species

aggression against intruders of other termite species

![]() the reception of vibrations sent by other termites

the reception of vibrations sent by other termites

![]() stabilization of the insect against physical disturbances

stabilization of the insect against physical disturbances

![]() the production of sound made by striking wood or plants

the production of sound made by striking wood or plants

![]() sounding an alert to notify other termites of danger

sounding an alert to notify other termites of danger

What does the question ask? What does the passage tell us about termite jaws?

What to skim for? Jaws.

What’s the answer in your own words? Hmm. This is an EXCEPT/LEAST/NOT question. For these you really have to answer four questions but get credit for only one. It’s best to treat these like a true/false question. First look at everything the passage says about jaws: Termites bite and kill other termites, they can receive vibrations on their mandibles (another word for jaws), they can make clicking noises, and they use their jaws to hang on to things that are moving.

Let’s check the answer choices:

(A) True. Bottom of the first paragraph.

(B) True. Top of the third paragraph.

(C) True. Last sentence of the passage.

(D) Not sure. Give this a question mark.

(E) True. They make a clicking sound.

One of these things is not like the other. The answer is (D).

Don’t be afraid of the “maybe.” If you’re not sure about an answer choice, don’t get hung up on it; just give it the “maybe” and move on to the next one. If you are stuck on a problem, walk away. Do a few other questions and then return to the one that was giving you trouble. What you learn when answering one question often turns out to be helpful on another. The correct answer to any problem will always support or parallel the main idea of the passage. If you find yourself down to two, and you are convinced that both answer choices are right, you are misreading something. Walk away and come back after a few questions. When you return, try paraphrasing the answer choices as well.

Special Format Questions

There are three types of questions you might see with Reading Comprehension:

1. Multiple Choice

2. Select All That Apply

3. Select In Passage

1. Multiple Choice—These are the standard, five-choice, multiple-choice questions we have been doing. There is only one correct answer choice and four wrong ones.

2. Select All That Apply—These are a variation of the old Roman numeral questions. Remember the ones that gave you three statements marked I, II, and III, and the answer choices that say, “I only,” “I and II only,” “I, II, and III”? These are the same, but without the answer choices. They will give you three statements, with a box next to each. You have to select all that apply. The process is the same. Find lead words and look for proof.

3. Select In Passage—In this case, ETS will ask you to select a sentence in the passage that makes a particular point, or raises a question, or provides proof, or some other function. These questions will appear primarily on short passages. If one appears on a longer passage, they will limit the scope to a particular paragraph. Again, the same rules apply. Pick a lead word. Put the question into your own words, and use Process of Elimination. To answer one of these, you will literally click on a particular sentence in the passage or paragraph.

Three things to keep in mind when working on Reading Comprehension:

1. You need only general knowledge of the passage to get started. Don’t get bogged down in the details.

2. Always answer the question in your own words before you look at the answer choices.

3. Look for reasons why an answer choice is wrong, not reasons why it is right. Park that thinking on your scratch paper. If your hand is not moving, you’re stuck. Move on.

Above all: Find proof in the passage for every answer you select. If there’s no proof, it’s not the right answer.