LSAT 2016

PART I All About the LSAT

CHAPTER 7 Law School

In this chapter, you will learn:

![]() The economic climate for lawyers

The economic climate for lawyers

![]() Factors to consider when choosing a school

Factors to consider when choosing a school

![]() How location affects your school choice

How location affects your school choice

![]() What to keep in mind when applying

What to keep in mind when applying

“It was the best of times, it was worst of times” fairly well sums up the current state of law school in the United States. It may be the worst of times for recent grads, but perhaps it is the best of times for prospective students.

While the bulk of this book is devoted to helping you improve your score on the LSAT, in this chapter we”ll step away from the nuts and bolts of test preparation to discuss the application process, the experience of attending law school, and the postgraduate realities for future law students.

Should I Go to Law School?

First of all, let”s state the obvious: law school is not for everyone. The hours are long, the workload is difficult, and competition at the best schools is fierce.

But if you prepare yourself adequately for the experience, it”s also likely to be one of the most invigorating, challenging, thrilling, demanding, edifying, exasperating, and satisfying experiences of your life. You will be equally exhausted and exhilarated.

The most brilliant people you”ll ever meet in your life, you”ll meet in law school. Your intellect and physical stamina will be pushed to the utmost limits of your endurance, and you”ll know both success and frustration. You”ll be given the know-how and means to effectuate real change in the lives of others, and you”ll learn the (little-known) fact that lawyers are some of the most generous people in the entire world, with a profound devotion to their friends, their community, and their loved ones. Yes, there will be many sleepless nights (some of them because you were studying), but you”ll arrive at the end of those three years of law school with your intellect sharpened and your critical reasoning skills honed to surgical precision.

Recently, however, schools have suffered some valid criticism that there are too many law school grads with too much debt and too few career opportunities. Recent law school grads enter the profession owing a median of approximately $75,000 in student loans, and the New York Timesreported that these grads were facing “one of the grimmest job markets in decades.”

Despite this reality, however, there has never been a better time to be a prospective law student. The journal of the American Bar Association reported that law schools could be admitting as many as 80 percent of their applicants for the fall of 2013, making it easier to gain admission to the best law schools even with a lower LSAT score or GPA. Better still, this trend is likely to continue for a few more years, making this year a great time to at least think about applying to law school.

I”ve Heard It”s a Bad Time to Apply to Law School

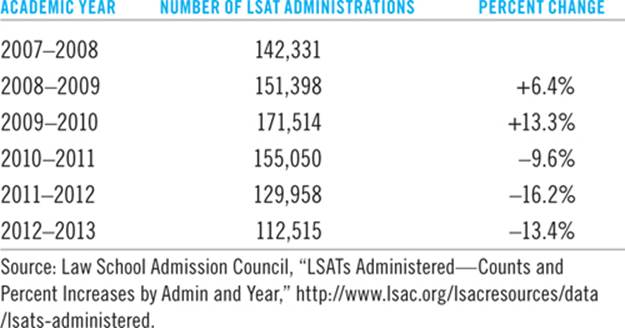

It”s no coincidence that the fall of 2008 saw a significant uptick in the number of LSAT administrations. September of that year marked the beginnings of the subprime mortgage crisis, soon followed by the collapse and near collapse of many banks and financial institutions. Law school has long been considered a safe port in a storm, and as more and more Americans were faced with rising unemployment, recent college grads and those who had been laid off turned to law school as a safe place to ride out the economic typhoon.

In the academic year 2007–2008, the period before the global economic crisis, approximately 142,000 LSATs were administered. But in 2008–2009, the first year of the crisis, that number climbed past 151,000, the highest number since 1990–1991 (not surprisingly, a period that also saw record unemployment rates). And in 2009–2010, the number of LSAT administrations reached an all-time high of 171,514, before the numbers started to dip again.

The discouraging employment numbers for new lawyers in 2012 were largely echoes of the 2008 financial crisis. But how, you might ask, can the previous financial turmoil possibly be affecting employment prospects today, when unemployment rates have actually been declining for the rest of the population? That”s mostly due to the legal profession”s unique hiring process.

For most nonlawyers, a job search involves checking the classifieds in our local newspaper, networking with family and friends, or going online to sites like CareerBuilder or Monster.com. Hiring in the legal profession works very differently. Most law students will get that first job out of law school through a process known as on-campus interviews (OCI). Almost all law schools have some variation of OCI.

Basically, the OCI process involves various law firms, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations sending representatives to a central location to conduct mass interviews with current law students. Afterward, some students will receive callback interviews. The initial interviews are relatively short, while the callback interviews can last all day and may require the student to meet with dozens of partners and associates. The callbacks are usually held on-site (at the firm”s offices), which may require the student to fly or drive extensively from city to city during the callback period.

Strangely enough, this initial OCI period usually takes place the month before a student begins his or her second year of law school (2L), even though the jobs won”t start until the summer after the second year of law school. Most students participating will only have two semesters” worth of grades, with another two years of law school still to follow.

The career services office (CSO) at your law school will prepare you for this rather grueling period with mock interviews and résumé reviews. Suffice to say that once you”ve secured your job as a summer associate, you”ll usually start in late May or June following your 2L year, working for a period of about 10 weeks. For many students working at larger firms, the summer associate job can be fairly lucrative, though savvy students will resist the urge to indulge in luxuries and use the paycheck to pay down debt. After the summer internship is over, firms will then decide which summer associates will receive offers of full-time employment.

Keep in mind, however, that even those successful candidates who receive offers of full-time employment still have to finish one more year of law school and pass the bar exam before they can be admitted to practice. For most students, this means graduating in May, taking the bar exam at the end of July, and receiving bar results around the beginning of November.

But think about the oddity of this time line: it basically means that law students are interviewing for full-time employment nearly two and a half years before they actually start the job.

It”s this strangely protracted hiring process coupled with the financial crisis that has led to the current stark employment numbers for new attorneys. The first batch of students affected by the financial collapse took the LSAT in the fall of 2008 and started law school in the fall of 2009. This also means that the first of these students affected by the financial collapse would have been going through OCI in the fall of 2010, with a graduation date of May 2012.

Unfortunately, in the fall of 2010, the unemployment rate for all Americans was still near record high levels, and many law firms canceled or seriously curtailed recruiting during OCI. Since OCI is traditionally where most students find their full-time jobs after law school, it meant that in May 2012, law schools began graduating many prospective attorneys who had not yet secured full-time employment. Those dire employment numbers were reported widely in the media, further depressing the number of LSAT test takers. At the same time, the economy began a gradual recovery, meaning graduate school was no longer the only viable option for young people coming out of undergrad.

All of this has led to the current dip in the number of LSAT administrations, which for 2012–2013 were the lowest since 2000–2001. Fewer prospective law students means fewer attorneys in four years” time. The unemployment rate, meanwhile, has dipped to its lowest levels since 2008. With the economy currently experiencing a recovery in terms of employment numbers, this should provide a self-correction to the employment prospects of future law students. So while it might be tough out there for recent grads, it”s a great time for those who are considering applying to law school.

Where Should I Apply?

Oddly, despite the stark realities faced by recent law school graduates, most of those very same graduates loved their law school experience. As reported in the Wall Street Journal, a survey of the class of 2012 at law schools across the country found that 90 percent of graduates gave their legal education a grade of A or B. Only 9 percent gave their law school a C grade, and 1 percent gave it a D. Even more revealing: no students in the survey gave their school a failing grade.

The critical reasoning skills you”ll acquire in law school translate well to any profession. But choosing which law schools to apply to can be daunting. There are currently 202 ABA-accredited law schools in the United States (in most states, attendance at an ABA-accredited school is a prerequisite to taking the bar). And although many of the programs, like Harvard and Yale, have obvious name-brand recognition, many excellent programs fly under the radar.

Realistically, there are only a few reasons most of us have heard of any law schools. First, some schools may be universally well known for academic excellence, as in the case of the Ivy League schools. Second, you might know of a law school at an institution you attended as an undergrad or that friends or family attended. Third, if a school is nearby, you”re probably familiar with it. And fourth, many people recognize law schools at institutions that are also home to an undergraduate program with a well-regarded football or basketball program. But none of these reasons for recognizing a name provides a reasonable basis for choosing a law school!

Many students begin their search for a law school by examining law school rankings. In a 2012 survey that asked prospective law students the most important factor in choosing a law school, 32 percent responded that law school rankings were their primary consideration. The best-known rankings are provided by U.S. News & World Report and are available online; you can find them by searching for “U.S. News law school rankings.”

But despite the primacy of the rankings for prospective students, the same survey found that after three years of law school, only 17 percent of law school grads would tell prospective students to use the rankings as the most important factor in choosing a law school. Instead, recent grads prioritized job placement, affordability/tuition, geographic location, and academic programming. The U.S. News & World Report website also does a great job of collecting these types of data for you so you can make an informed decision.

I Know I Want to Go to Law School, But I Don”t Know if I Want to Be a Lawyer

Many prospective law students know they want to go to law school but have doubts about actually being a lawyer. They may be attracted to the prospect of the intellectual rigors of law school. The prospect of spending long days in a corporate law office is less appealing.

Thankfully, the law is not a monolithic profession, and a Juris Doctor is the Swiss Army knife of graduate degrees. The day in the life of a federal prosecutor is going to be radically different from that of a solo practitioner who specializes in family law. From public-interest or government work to law enforcement to corporate megafirms, the law offers a wide spectrum of experiences. Some lawyers may specialize in litigation; others may spend their entire career in the legal profession without ever setting foot in front of a jury.

Big firms tend to offer big paychecks, with starting salaries around $160,000 a year. But Big Law, as it is affectionately known, also requires associates to work long hours. Some associates thrive in the pressure cooker of Big Law and relish the experience, but others may prefer more leisure time and choose to work for a small firm or government agency. For students considering public-interest or government work, this does usually mean a smaller salary, but many schools now offer loan repayment assistance programs (LRAPs), which provide debt forgiveness of government-backed student loans after a predetermined period. A complete list of schools offering LRAPs can be found through the American Bar Association website at http://apps.americanbar.org/legalservices/probono/lawschools/pi_lrap.html.

Also consider creating your own specialization in law school. Although there isn”t really such a thing as a “major” in law schools, students can certainly create their own concentrations. The first-year curriculum is largely prescribed, but students have great latitude in choosing their course work in the second and third years of school. Promising practice areas with growth potential include alternative-energy law, health care, copyright and intellectual property, and financial regulation. Lisa L. Abrams”s The Official Guide to Legal Specialties is a great place to begin when considering different practice areas, and Federal Reports Inc.”s “600+ Things You Can Do with a Law Degree (Other than Practice Law)” provides a thorough survey of alternative career prospects for law school grads and attorneys.

Do I Need to Attend Law School in the State Where I Plan to Practice?

One of the strangest things you”ll learn in law school is that law school doesn”t really prepare you for the bar exam. Certainly, law school teaches you to “think like a lawyer” (a phrase you”ll hear over and over), but that doesn”t mean you”ll have all the applicable statutes memorized by the time you graduate.

For most students, this means taking a six-week bar prep class immediately following graduation. Although many companies offer competing courses, the landscape is basically dominated by two firms: BarBri and Kaplan PMBR. The courses are offered for all 50 states and Washington, DC, meaning you can go to law school anywhere in the country and still return to the state in which you intend to practice in order to take that particular bar exam.

It”s also important to remember that most law schools offer an identical first-year curriculum, with courses in civil procedure, constitutional law, contracts, criminal law, property, torts, and legal research/writing. And the fact of the matter is, the laws in most states are fairly uniform. The U.S. Constitution in Rhode Island, after all, is the same U.S. Constitution used in Alaska. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure are identical in all states because they”re federal rules. Contracts are governed by the Uniform Commercial Code, which has been enacted in one form or another in all 50 states. And property law finds its roots in the common-law practices of medieval England (explaining why a landlord is called a “land lord” in the first place).

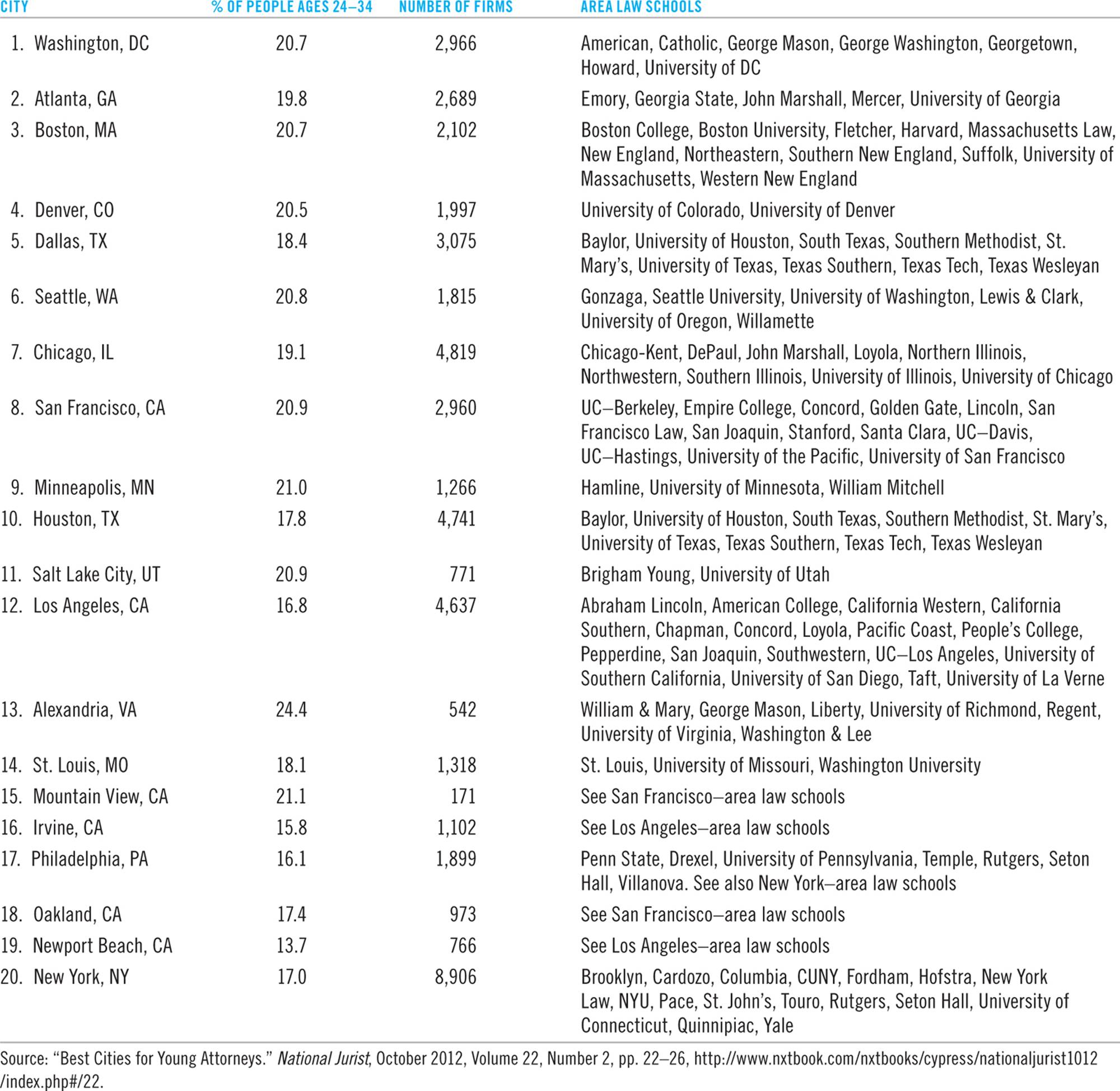

That being said, there are some advantages to going to a law school in the place where you ultimately plan to practice. A primary consideration for many in choosing a law school is the portability of the degree. Portability in a law degree basically means what the name implies: the ability to take your law degree, travel anywhere in the country, and still get a job. The more prestigious the program, the more portable the degree.

Students looking at lower-ranked programs may benefit from considering their postgraduate career plans. A degree from Northeastern University and a degree from Harvard both give graduates access to the Boston legal market, but the Harvard degree is ultimately more portable. However, if the student intends to stay in the Boston area, a Northeastern degree could be a great (and more affordable) choice.

Also remember that the law is very much a relationship-driven profession. Your law school classmates are also future judges, hiring partners, and opposing counsel. Alumni of the same school tend to look out for each other in the hiring process or when offering referrals, and established law schools with extensive alumni networks may offer a competitive advantage over law schools of more recent provenance. Thus, while U.S. News & World Report may rank UCLA as a better law school than Emory (number 15 versus number 24), for students practicing in Atlanta, Emory may be the better choice.

Finally, wherever you choose to go to school, make sure you”re going to be happy. You”re going to be spending at least three long, stressful years in that place, and quality of life is an important consideration. The University of Minnesota School of Law offers a great program, but if you don”t like cold weather, you”re likely to be unhappy for about six months of the year. Love the sunshine? Maybe the University of Washington–Seattle isn”t a good fit. If it”s important to be home for Thanksgiving, a law school on the opposite side of the country may not be right for you.

Best Law Schools for Standard of Living

Best Cities for Young Attorneys

What Else Do I Need to Do to Complete My Law School Applications?

The LSAT and GPA are the primary components used in making admissions decisions, weighed in about a two-to-one ratio in favor of the LSAT. Law schools believe that these numbers are the most reliable predictors of your success in law school. Your undergraduate GPA is viewed as a rough measure of your ability to work hard and apply yourself, and your LSAT score is believed to be a good measure of your native intellectual ability.

Thus, you can use those two numbers to make a reasonably accurate prediction about whether you”re likely to gain admission to a particular law school. The Law School Admissions Council, which creates and administers the LSAT along with processing your law school applications through its Credential Assembly Service, hosts an LSAT/GPA calculator on its website at http://officialguide.lsac.org.

You can use the calculator not only to gauge your chances of admission, but also to help determine your goal LSAT score. If it has always been your dream to attend the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, Pitt”s website will tell you that for the most recent class, the median LSAT score was 158, and the median GPA was 3.34. But what if you have a 3.0 GPA? You can plug your GPA into the GPA/LSAT calculator and play around with different LSAT scores to find the score with which you have roughly a 50% chance of being admitted (in this case, an LSAT score of 162). This gives you a more personalized target score when prepping for your LSAT.

That”s not to say you should limit your applications solely to those schools that offer you the best chance of admission. Everyone should reach a little bit beyond what his or her numbers would indicate are “safe” prospects. You are more than two numbers on a grid, after all, and every school admits a few students who don”t line up numerically with the rest of the class, on the basis of the strength of the qualitative portions of their applications.

What do these “qualitative” components consist of? For most schools, your application checklist will include the following:

![]() Personal statement (two to three pages)

Personal statement (two to three pages)

![]() Recommendations or evaluations (two to three)

Recommendations or evaluations (two to three)

![]() Résumé or work history

Résumé or work history

![]() List of honors and extracurricular activities

List of honors and extracurricular activities

Don”t overlook the importance of these more subjective portions of your application! Remember, applicants at most schools are a self-selecting group. That is to say, the applicants tend to resemble each other, numerically at least. If you have a 3.2 GPA and a 158 on your LSAT, you”re probably not likely to apply to Yale. You”re more likely to apply to schools where you have a better chance of acceptance. And since most people operate in a similarly rational fashion, most other applicants are going to look just like you on paper.

Ultimately, the rest of your application is there to create points of difference between yourself and the competition. Why do you deserve to take a spot at this particular law school over someone who is your numerical twin? And in that regard, your personal statement is likely to prove the third most important part of your application after LSAT and GPA.

That isn”t to diminish the importance of well-written, detailed recommendation letters or a résumé highlighting significant accomplishments. But ask yourself: Do they really create points of difference between myself and my peers? After all, ideally, most people will ask for letters from college professors. And ideally, those professors will have nice things to say about you and your class work. But if every letter says great things, then how does that create a point of difference?

The same goes for résumés. The bulk of law school applicants are relatively young. In 2011, just over 80 percent of law school applicants were younger than 30, and 62 percent of applicants were younger than 25. For most young people, this means fairly thin résumés at this juncture of their professional careers. For those coming directly out of undergrad into law school, this may even mean no professional experience. Again, this isn”t to diminish the importance of a great résumé; your professional experience, internships, leadership roles, and community involvement can only help your candidacy. But they may not make you as different as you imagine, especially when so many law students come from such similar backgrounds.

So it comes down to the personal statement. Don”t overlook this very important document, and don”t try to write the entire thing in an evening. Devote substantial time to brainstorming, writing, editing, and revising. And don”t merely recycle the personal statement you used to get into your undergraduate university! The person you were at age 17 is very different from the person you are now.

All law schools require you to submit a personal essay as a part of your application, and for the most part, you should be able to use the same personal statement for all of your applications. Typically, the personal statement is a short (two to three pages) piece of writing designed to give the admissions committee insight into your character, personality, and motivations for attending law school. It should be a personal statement, containing information not found elsewhere on your application, not merely a narrative version of your résumé. And unless you plan to practice public-interest law, it shouldn”t necessarily be about why you are a good person. Too many law students craft personal statements containing vague promises to “change the world” if they have a law degree. But if your résumé doesn”t demonstrate that you”ve ever engaged in significant community involvement, volunteerism, or charitable work, then why should the admissions officer believe that”s all going to change once you”ve completed law school?

Instead, think of your personal statement as your interview on paper. Most law schools don”t require or even offer an interview, so this is the chance to share who you are. What stories do you tell people when you meet them for the first time? How do you spend your time when you”re not in school? What have been the formative events in your life? What are your hobbies or passions? What makes you different from absolutely everyone else?

You”ll also want to devote significant time to proofreading. Your personal statement also functions as a technical writing sample that the admissions committee will scrutinize for grammar, mechanics, style, organization, and clarity. Admissions officers are far more likely to read your personal statement for this purpose than they are to read your response to the Writing Sample section of the LSAT. For that reason, it”s a good idea to take a draft of your personal statement to your college writing center or your prelaw adviser. If you enlist proofreaders, make sure they understand that you want critical feedback, not merely validation of a job well done.

You are about to embark on a truly remarkable journey, one you will look back upon as being the most exciting, most transformative, and most exhausting few years of your life. On behalf of everyone at McGraw-Hill Education, we wish you all the best and hold nothing but the highest hopes for your future success in law school and beyond!