Barron's SAT, 26th edition (2012)

Part 1. GET ACQUAINTED WITH THE SAT

Introduction:

Let’s Look at the SAT

![]()

|

• What Is the SAT? |

|

• The Critical Reading Sections |

|

• The Mathematics Sections |

|

• The Use of Calculators on the SAT |

|

• The Writing Skills Sections |

|

• Winning Tactics for the SAT |

WHAT IS THE SAT?

The he SAT is a standardized exam that most high school students take before applying for college. Genereally, students take the SAT for the first time as high school juniors. If they do very well, they are through. If they want to try to boost their scores, they can take the test a second or even a third time.

The SAT tests you in three areas: reading, writing, and mathematical reasoning. As a result, each time you take the test you get three separate scores: a critical reading score, a writing score, and a math score. Each of these scores will fall somewhere between 200 and 800. For each of the three parts of the test, the median score is approximately 500: about 50 percent of all students score below 500 and about 50 percent score 500 or above. In talking about their results, students often add the three scores and say, “Ron got a 1560,” or “Hermione got a 2400.” (Total scores range from 600 to 2400, with a median of about 1500.)

HOW DO I SIGN UP TO TAKE THE SAT?

Online: Go to www.collegeboard.org

Have available your social security number and/or date of birth.

Pay with a major credit card.

Note: If you are signing up for Sunday testing, or if you have a visual, hearing, or learning disability and plan to sign up for the Services for Students with Disabilities Program, you cannot register online. You must register by mail well in advance.

By mail: Get a copy of the SAT Program Registration Bulletin from your high school guidance office or from the College Board. (Write to College Board SAT, P.O. Box 6200, Princeton, NJ 08541-6200, or phone the College Board office in Princeton at 866-756-7346.)

Pay by check, money order, fee waiver, or credit card.

WHAT IS SCORE CHOICE?

In 2009, the College Board instituted a Score Choice policy for the SAT. Now, you may be able to take the SAT as many times as you want, receive your scores, and then choose which scores the colleges to which you eventually apply will see. In fact, you don’t have to make that choice until your senior year when you actually send in your college applications.

Here’s How Score Choice Works

Suppose you take the SAT in May of your junior year and again in October of your senior year, and your October scores are higher than your May scores. Through Score Choice you can send the colleges only your October scores; not only will the colleges not see your May scores, they won’t even know that you took the test in May. The importance of the Score Choice policy is that it can significantly lessen your anxiety anytime you take the SAT. If you have a bad day

|

CAUTION |

|

Most colleges allow you to use Score Choice; some do not. Some want to see all of your scores. Be sure to go to http://sat.collegeboard.org/register/ sat-score-choice to check the score-use policy of the colleges to which you hope to apply. |

when you take the SAT for the first time, and your scores aren’t as high as you had hoped, relax: you can retake it at a later date, and if your scores improve, you will never have to report the lower scores. Even if you do very well the first time you take the SAT, you can still retake it in an attempt to earn even higher scores. If your scores do improve, terrific—those are the scores you will report. If your scores happen to go down, don’t worry—you can send only your original scores to the colleges and they will never even know that you retook the test. In fact, you can take the test more than twice. No matter how many times you take the SAT, because of Score Choice, you can send in only the scores that you want the colleges to see.

WHAT IS THE FORMAT OF THE SAT?

The SAT is a 4-hour plus exam divided into ten sections; but because you should arrive a little early and because time is required to pass out materials, read instructions, collect the test, and give you two 10-minute breaks between sections, you should assume that you will be in the testing room for 4½ to 5 hours.

Although the SAT contains ten sections, your scores will be based on only nine of them: five 25-minute multiple-choice sections (two math, two critical reading, and one writing skills); two 20-minute multiple-choice sections (one math and one critical reading); one 10-minute multiple-choice section (writing skills); and one 25-minute essay-writing section. The tenth section is an additional 25-minute multiple-choice section that may be on math, critical reading, or writing skills. It is what the Educational Testing Service (ETS) calls an “equating” section, but most people refer to it as the “experimental” section. ETS uses it to test new questions for use on future exams. However, because this section typically is identical in format to one of the other sections, you have no way of knowing which section is the experimental one, and so you must do your best on all ten sections.

|

CHECKLIST: WHAT SHOULD I BRING TO THE TEST CENTER? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE CRITICAL READING SECTIONS

There are two types of questions on the critical reading portion of the SAT: sentence completion questions and passage-based reading questions.

Examples of each type appear in this chapter. Later, in Chapters 1 and 2, you will learn important strategies for handling both types. The 67 sentence completion and passage-based reading questions are divided into three sections, each of which has its own format. Below is one typical format for the SAT. You should expect to see something like the following on your test, although not necessarily in this order:

|

24-Question Critical Reading Section |

||

|

Questions 1–8 |

sentence completion |

|

|

Questions 9–12 |

passage-based reading (short passages) |

|

|

Questions 13–24 |

passage-based reading (long passage) |

|

|

24-Question Critical Reading Section |

||

|

Questions 1–5 |

sentence completion |

|

|

Questions 6–9 |

passage-based reading (short passages) |

|

|

Questions 10–24 |

passage-based reading (long passages) |

|

|

19-Question Critical Reading Section |

||

|

Questions 1–6 |

sentence completion |

|

|

Questions 7–19 |

passage-based reading (long passages) |

|

As you see, most of the critical reading questions on the SAT directly test your passage-based reading skills.

NOTE

If the 25-minute experimental section on your SAT is a critical reading section, it will follow exactly the same format as one of the two 25-minute sections described above. Since, however, there will be no way for you to know which one of the 25-minute critical reading sections on your test is experimental, you must do your best on each one.

Pay particular attention to how the sections described above are organized. These sections contain groups of sentence completion questions arranged roughly in order of difficulty: they start out with easy warm-up questions and get more difficult as they go along. The passage-based reading questions, however, are not arranged in order of difficulty. Instead, they follow the organization of the passage on which they are based: questions about material found early in the passage precede questions about material occurring later. This information can help you pace yourself during the test.

Here are examples of the specific types of critical reading questions you can expect.

Sentence Completions

Sentence completion questions ask you to fill in the blanks. In each case, your job is to find the word or phrase that best completes the sentence and conveys its meaning.

Directions: Choose the word or set of words that, when inserted in the sentence, best fits the meaning of the sentence as a whole.

Brown, this biography suggests, was an ____ employer, giving generous bonuses one day, ordering pay cuts the next.

(A) indifferent

(B) objective

(C) unpredictable

(D) ineffectual

(E) unobtrusive

Note how the phrases immediately following the word employer give you an idea of Brown’s character and help you select the missing word. Clearly, someone who switches back and forth in this manner would be a difficult employer, but the test-makers want the precise word that characterizes Brown’s arbitrary behavior.

Insert the different answer choices in the sentence to see which make the most sense.

(A) Was Brown an indifferent (uncaring or mediocre) employer? Not necessarily: he may or may not have cared about what sort of job he did.

(B) Was Brown an objective (fair and impartial) employer? You don’t know: you have no information about his fairness and impartiality.

(C) Was Brown an unpredictable employer? Definitely. A man who gives bonuses one day and orders pay cuts the next clearly is unpredictable—no one can tell what he’s going to do next. The correct answer appears to be Choice C.

To confirm your answer, check the remaining two choices.

(D) Was Brown an ineffectual (weak and ineffective) employer. Not necessarily: though his employees probably disliked not knowing from one day to the next how much pay they would receive, he still may have been an effective boss.

(E) Was Brown an unobtrusive (hardly noticeable; low-profile) employer? You don’t know: you have no information about his visibility in the company.

The best answer definitely is Choice C.

Sometimes sentence completion questions contain two blanks rather than one. In answering these double-blank sentences, you must be sure that both words in your answer choice make sense in the original sentence.

For a complete discussion of all the tactics used in handling sentence completion questions, turn to Chapter 1.

Passage-Based Reading

Passage-based reading questions ask about a passage’s main idea or specific details, the author’s attitude to the subject, the author’s logic and techniques, the implications of the discussion, or the meaning of specific words.

Directions: The passage below is followed by questions based on its content. Answer the questions on the basis of what is stated or implied in that passage.

Certain qualities common to the sonnet should be noted. Its definite

restrictions make it a challenge to the artistry of the poet and call for all

the technical skill at the poet’s command. The more or less set rhyme

patterns occurring regularly within the short space of fourteen lines afford a

Line (5) pleasant effect on the ear of the reader, and can create truly musical

effects. The rigidity of the form precludes too great economy or too great

prodigality of words. Emphasis is placed on exactness and perfection of

expression. The brevity of the form favors concentrated expression of

ideas or passion.

1. The author’s primary purpose is to

(A) contrast different types of sonnets

(B) criticize the limitations of the sonnet

(C) identify the characteristics of the sonnet

(D) explain why the sonnet has lost popularity as a literary form

(E) encourage readers to compose formal sonnets

The first question asks you to find the author’s main idea. In the opening sentence, the author says certain qualities of the sonnet should be noted. In other words, he intends to call attention to certain of its characteristics, identifying them. The correct answer is Choice C.

You can eliminate the other answers with ease. The author is upbeat about the sonnet: he doesn’t say that the sonnet has limitations or that it has become less popular. You can eliminate Choices B and D.

Similarly the author doesn’t mention any different types of sonnets; therefore, he cannot be contrasting them. You can eliminate Choice A.

And although the author talks about the challenge of composing formal sonnets, he never invites his readers to try to write them. You can eliminate Choice E.

2. In line 4 “afford” most nearly means

(A) initiate

(B) exaggerate

(C) are able to pay for

(D) change into

(E) provide

NOTE

Even if you felt uneasy about eliminating all four of these incorrect answer choices, you should have been comfortable eliminating two or three of them. Thus, even if you were not absolutely sure of the correct answer, you would have been in an excellent position to guess.

The second question asks you to figure out a word’s meaning from its context. Substitute each of the answer choices in the original sentence and see which word or phrase makes most sense. Some make no sense at all: the rhyme patterns that the reader hears certainly are not able to pay for any pleasant effect. You can definitely eliminate Choice C. What is it exactly that these rhyme patterns do? The rhyme patterns have a pleasant effect on the ear of the listener; indeed, they provide (furnish or afford) this effect. The correct answer is Choice E.

NOTE

Because you can eliminate at least one of the answer choices, you are in a good position to guess the correct answer to this question.

3. The author’s attitude toward the sonnet form can best be described as one of

(A) amused toleration

(B) grudging admiration

(C) strong disapprobation

(D) effusive enthusiasm

(E) scholarly appreciation

The third question asks you to figure out how the author feels about his subject. All the author’s comments about the sonnet are positive: he approves of this poetic form. You can immediately eliminate Choice C, strong disapprobation or disapproval.

You can also eliminate Choice A, amused toleration or forbearance: the author is not simply putting up with the sonnet form in a good-humored, somewhat patronizing way; he thinks well of it.

Choices B and D are somewhat harder to eliminate. The author does seem to admire the sonnet form. However, his admiration is unforced: it is not grudging or reluctant. You can eliminate Choice B. Likewise, the author is enthusiastic about the sonnet. However, he doesn’t go so far as to gush: he’s not effusive. You can eliminate Choice D.

The only answer that properly reflects the author’s attitude is Choice E, scholarly appreciation.

See Chapter 2 for tactics that will help you handle the entire range of critical reading questions.

THE MATHEMATICS SECTIONS

There are two types of questions on the mathematics portion of the SAT: multiple-choice questions and grid-in questions.

Examples of both types appear in this chapter. Later, in Chapter 8, you will learn several important strategies for handling each type.

There are 54 math questions in all, divided into three sections, each of which has its own format. You should expect to see:

• a 25-minute section with 20 multiple-choice questions

• a 25-minute section with 8 multiple-choice questions followed by 10 student-produced response questions (grid-ins)

• a 20-minute section with 16 multiple-choice questions

NOTE

If the 25-minute experimental section on your SAT is a mathematics section, it will follow exactly the same format as one of the two 25-minute sections described above. Since, however, there will be no way for you to know which section is experimental, you must do your best on each one.

Within each of the three math sections, the questions are arranged in order of increasing difficulty. The first few multiple-choice questions are quite easy; they are followed by several of medium difficulty; and the last few are considered hard. The grid-ins also proceed from easy to difficult. As a result, the amount of time you spend on any one question will vary greatly.

Note that, in the section that contains eight multiple-choice questions followed by ten grid-in questions, questions 7 and 8 are hard multiple-choice questions, whereas questions 9–11 and 12–15 are easy and medium grid-in questions, respectively. Therefore, for many students, it is advisable to skip questions 7 and 8 and to move on to the easy and medium grid-in questions.

Multiple-Choice Questions

On the SAT, all but 10 of the questions are multiple-choice questions. Although you have certainly taken multiple-choice tests before, the SAT uses a few different types of questions, and you must become familiar with all of them. By far, the most common type of question is one in which you are asked to solve a problem. The straightforward way to answer such a question is to do the necessary work, get the solution, look at the five choices, and choose the one that corresponds to your answer. In Chapter 8 other techniques for answering these questions are discussed, but now let’s look at a couple of examples.

EXAMPLE 1

What is the average (arithmetic mean) of all the even integers between –5 and 7?

(A) 0

(B) ![]()

(C) 1

(D) ![]()

(E) 3

To solve this problem requires only that you know how to find the average of a set of numbers. Ignore the fact that this is a multiple-choice question. Don’t even look at the choices.

• List the even integers whose average you need: –4, –2, 0, 2, 4, 6. (Be careful not to leave out 0, which is an even integer.)

• Calculate the average by adding the six integers and dividing by 6.

![]()

• Having found the average to be 1, look at the five choices, see that 1 is Choice C, and blacken C on your answer sheet.

EXAMPLE 2

A necklace is formed by stringing 133 colored beads on a thin wire in the following order: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet; red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. If this pattern continues, what will be the color of the 101st bead on the string?

(A) Orange

(B) Yellow

(C) Green

(D) Blue

(E) Indigo

Again, you are not helped by the fact that the question, which is less a test of your arithmetic skills than of your ability to reason, is a multiple-choice question. You need to determine the color of the 101st bead, and then select the choice that matches your answer.

The seven colors keep repeating in exactly the same order.

|

Color: |

red |

orange |

yellow |

green |

blue |

indigo |

violet |

|

|

Bead |

||||||||

|

number: |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

etc. |

• The violet beads are in positions 7, 14, 21, . . ., 70, . . ., that is, the multiples of 7.

• If 101 were a multiple of 7, the 101st bead would be violet.

• But when 101 is divided by 7, the quotient is 14 and the remainder is 3.

• Since 14 × 7 = 98, the 98th bead completes the 14th cycle, and hence is violet.

• The 99th bead starts the next cycle; it is red. The 100th bead is orange, and the 101st bead is yellow.

• The answer is B.

In contrast to Examples 1 and 2, some questions require you to look at all five choices in order to find the answer. Consider Example 3.

NOTE

Did you notice that the solution didn’t use the fact that the necklace consisted of 133 beads? This is unusual; occasionally, but not often, a problem contains information you don’t need.

EXAMPLE 3

If a and b are both odd integers, which of the following could be an odd integer?

(A) a + b

(B) a2 + b2

(C) (a + 1)2 + (b – 1)2

(D) (a + 1)(b – 1)

(E) ![]()

The words which of the following alert you to the fact that you will have to examine each of the five choices to determine which one satisfies the stated condition, in this case that the quantity could be odd. Check each choice.

• The sum of two odd integers is always even. Eliminate A.

• The square of an odd integer is odd; so a2 and b2 are each odd, and their sum is even. Eliminate B.

• Since a and b are odd, (a + 1) and (b – 1) are even; so (a + 1)2 and (b – 1)2 are also even, as is their sum. Eliminate C.

• The product of two even integers is even. Eliminate D.

• Having eliminated A, B, C, and D, you know that the answer must be E. Check to be sure: ![]() need not even be an integer (e.g., if a = 1 and b = 5), but it could be. For example, if a = 3 and b = 5, then

need not even be an integer (e.g., if a = 1 and b = 5), but it could be. For example, if a = 3 and b = 5, then

![]()

which is an odd integer. The answer is E.

Another kind of multiple-choice question that appears on the SAT is the Roman numeral-type question. These questions actually consist of three statements labeled I, II, and III. The five answer choices give various possibilities for which statement or statements are true. Here is a typical example.

EXAMPLE 4

If x is negative, which of the following must be true?

I. x3 < x 2

II. x + ![]() < 0

< 0

III. x = ![]()

(A) I only

(B) II only

(C) I and II only

(D) II and III only

(E) I, II, and III

• To solve this problem, examine each statement independently to determine if it is true or false.

I. If x is negative, then x3 is negative and so must be less than x2, which is positive. (I is true.)

II. If x is negative, so is ![]() , and the sum of two negative numbers is negative. (II is true.)

, and the sum of two negative numbers is negative. (II is true.)

III. The square root of a number is never negative, and so ![]() could not possibly equal x. (III is false.)

could not possibly equal x. (III is false.)

• Only I and II are true. The answer is C.

NOTE

You should almost never leave out a Roman numeral-type question. Even if you can’t solve the problem completely, there should be at least one of the three Roman numeral statements that you know to be true or false. On the basis of that information, you should be able to eliminate two or three of the answer choices. For instance, in Example 4, if all you know for sure is that statement I is true, you can eliminate choices B and D. Similarly, if all you know is that statement III is false, you can eliminate choices D and E. Then, as you will learn, you must guess between the remaining choices.

Grid-in Questions

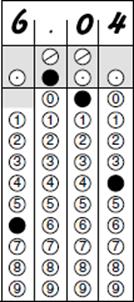

Ten of the mathematics questions on the SAT are what the College Board calls student-produced response questions. Since the answers to these questions are entered on a special grid, they are usually referred to as grid-in questions. Except for the method of entering your answer, this type of question is probably the one with which you are most familiar. In your math class, most of your homework problems and test questions require you to determine an answer and write it down, and this is what you will do on the grid-in problems. The only difference is that, once you have figured out an answer, it must be recorded on a special grid, such as the one shown below, so that it can be read by a computer. Here is a typical grid-in question.

EXAMPLE 5

At the diner, John ordered a sandwich for $3.95 and a soda for 85¢. A sales tax of 5% was added to his bill, and he left the waitress a $1 tip. What was the total cost, in dollars, of John’s lunch?

• Calculate the cost of the food: $3.95 + $0.85 = $4.80

• Calculate the tax (5% of $4.80): .05 × $4.80 = $0.24

• Add the cost of the food, tax, and tip: $4.80 + $0.24 + $1.00 = $6.04

To enter this answer, you write 6.04 (without the dollar sign) in the four spaces at the top of the grid, and blacken the appropriate oval under each space. In the first column, under the 6, you blacken the oval marked 6; in the second column, under the decimal point, you blacken the oval with the decimal point; in the third column, under the 0, you blacken the oval marked 0; and, finally, in the fourth column, under the 4, you blacken the oval marked 4.

Always read each grid-in question very carefully. Example 5 might have asked for the total cost of John’s lunch in cents. In that case, the correct answer would have been 604, which would be gridded in, without a decimal point, using only three of the four columns (see below).

Note that the only symbols that appear in the grid are the digits from 0 to 9, a decimal point, and a fraction bar (/). The grid does not have a minus sign, so answers to grid-in problems can never be negative. In Introduction to the Math Sections, in Part Three, you will learn some important tactics for answering grid-in questions and will be able to practice filling in grids. You will also learn the special rules concerning the proper way to grid in fractions, mixed numbers, and decimals that won’t fit in the grid’s four columns. When you take the diagnostic test, just enter your answers to the grid-in questions exactly as was done in Example 5.

NOTE

Any multiple-choice question whose answer is a positive number less than 10,000 could be a grid-in question. If Example 1 had been a grid-in question, you would have solved it in exactly the same way: you would have determined that the average of the six numbers is 1; but then, instead of looking for 1 among the five choices, you would have entered the number 1 on a grid. The mathematics is no harder on grid-in questions than on multiple-choice questions. However, if you don’t know how to solve a problem correctly, it is harder to guess at the right answer, since there are no choices to eliminate.

CALCULATOR TIPS

• Bring a calculator to the test: it’s not required, but it sometimes can help.

• Don’t buy a new calculator the night before the SAT. If you need one, buy one now and become familiar with it. Do all the practice exams in this book with the calculator you plan to take to the test—probably the same calculator you use in school.

• The College Board recommends a scientific calculator with parentheses keys, ( ); a reciprocal key, ![]() ; and an exponent key, y or ^.

; and an exponent key, y or ^.

• Use your calculator when you need to; ignore it when you don’t. Most students use calculators more than they should. You can solve many problems without doing any calculations—mental, written, or calculator-assisted.

• Throughout this book, the icon ![]() will be placed next to a problem where the use of a calculator is recommended. As you will see, this judgment is subjective. Sometimes a question can be answered in a few seconds, with no calculations whatsoever, if you see the best approach. In that case, the use of a calculator is not recommended. If you don’t see the easy way, however, and have to do some arithmetic, you may prefer to use a calculator.

will be placed next to a problem where the use of a calculator is recommended. As you will see, this judgment is subjective. Sometimes a question can be answered in a few seconds, with no calculations whatsoever, if you see the best approach. In that case, the use of a calculator is not recommended. If you don’t see the easy way, however, and have to do some arithmetic, you may prefer to use a calculator.

• No SAT problem ever requires a lot of tedious calculation. However, if you don’t see how to avoid calculating, just do it—don’t spend a lot of time looking for a shortcut that will save you a little time!

THE WRITING SKILLS SECTIONS

There are three types of questions on the writing skills section of the SAT:

1. Improving sentences

2. Identifying sentence errors

3. Improving paragraphs

Examples of each type of question appear in this section. Later, in Chapter 6, you will find some tips on how to handle each one.

The writing skills section on your test will contain 49 questions. The two sections break down as follows:

|

35-Question Writing Skills Section (25 minutes) |

|

|

Questions 1–11 |

Improving sentences |

|

Questions 12–29 |

Identifying sentence errors |

|

Questions 30–35 |

Improving paragraphs |

|

14-Question Writing Skills Section (10 minutes) |

|

|

Questions 1–14 |

Improving sentences |

Here are examples of the specific types of writing skills questions you can expect.

Improving Sentences

Improving sentences questions ask you to spot the form of a sentence that works best. Your job is to select the most effective version of a sentence.

Directions: Some or all parts of the following sentences are underlined. The first answer choice, (A), simply repeats the underlined part of the sentence. The other four choices present four alternative ways to phrase the underlined part. Select the answer choice that produces the most effective sentence, one that is clear and exact.

Example:

Walking out the hotel door, the Danish village with its charming stores and bakeries beckons you to enjoy a memorable day.

(A) Walking out the hotel door, the Danish village with its charming stores and bakeries beckons you to enjoy a memorable day.

(B) Walking out the hotel door, the Danish village with its charming stores and bakeries is beckoning you to enjoy a memorable day.

(C) While you were walking out the hotel door, the Danish village with its charming stores and bakeries beckons you to enjoy a memorable day.

(D) As you walk out the hotel door, the Danish village with its charming stores and bakeries beckons you to enjoy a memorable day.

(E) Walking out the hotel door, the Danish village with its charming stores and bakeries beckon you to enjoy a memorable day.

The underlined sentence begins with a participial phrase, Walking out the hotel door. In such cases, be on the lookout for a possible dangling modifier. A dangling participial phrase is a phrase that does not refer clearly to another word in the sentence. Ask yourself who or what is walking out the hotel door. Certainly not the village! To improve the sentence, you must fix the dangling modifier, replacing the initial participial phrase with a clause. Both Choices C and D do so. However, Choice C introduces an error involving the sequence of tenses: the verb were walking is in the past tense, not the present. Only Choice D corrects the dangling participial phrase without introducing any fresh errors. It is the correct answer.

To reach the answer above, you took a shortcut. You suspected the presence of a dangling participial phrase, focused on the two answer choices that replaced the participial phrase Walking out the hotel door with different wording, and selected the answer choice that produced a clear, effective sentence. Even if you had not taken this shortcut, however, you could have figured out the correct answer by working your way through all the answer choices, noting any changes to the original sentence.

Identifying Sentence Errors

Identifying sentence errors questions ask you to spot something wrong. Your job is to find the error in the sentence, not to fix it.

Directions: These sentences may contain errors in grammar, usage, choice of words, or idioms. Either there is just one error in a sentence or the sentence is correct. Some words or phrases are underlined and lettered; everything else in the sentence is correct.

If an underlined word or phrase is incorrect, choose that letter; if the sentence is correct, select No error.

Example:

![]() the incident was over,

the incident was over, ![]() passengers nor the bus driver

passengers nor the bus driver ![]() able to identify the youngster who

able to identify the youngster who ![]() the disturbance.

the disturbance. ![]()

The error here is lack of agreement between the subject and the verb. In a neither-nor construction, the verb agrees in number with the noun or pronoun that comes immediately before it. Here, the noun that immediately precedes the verb is the singular noun driver. Therefore, the correct verb form is the singular verb was. The error is in C.

Improving paragraphs

Improving paragraphs questions require you to correct the flaws in a student essay. Some questions involve rewriting or combining separate sentences to come up with a more effective wording. Other questions involve reordering sentences to produce a better organized argument.

Directions: The passage below is the unedited draft of a student’s essay. Parts of the essay need to be rewritten to make the meaning clearer and more precise. Read the essay carefully.

The essay is followed by six questions about changes that might improve all or part of the organization, development, sentence structure, use of language, appropriateness to the audience, or use of standard written English. Choose the answer that most clearly and effectively expresses the student’s intended meaning.

NOTE

Remember, this essay is a rough draft. It is likely to contain grammatical errors and awkward phrasing. Do not assume it is exemplary prose.

(1) This fall I am supposed to vote for the first time. (2) However, I do not know whether my vote will count. (3) Ever since the 2008 presidential election, I have been reading in the newspapers about problems in our voting system. (4) Some days I ask myself whether there is any point in me voting at all. (5) From the papers, I know our methods of counting votes are seriously flawed. (6) We use many different kinds of technology in voting, and none of them work perfectly. (7) And the newest method, electronic voting technology, is the worst of all.

Sentence 3 would make the most sense if placed after

(A) Sentence 1

(B) Sentence 4

(C) Sentence 5

(D) Sentence 6

(E) Sentence 7

The best way to improve this opening paragraph is to place sentence 3 immediately after sentence 4. The opening section would then read: This fall I am supposed to vote for the first time. However, I do not know whether my vote will count. Some days I ask myself whether there is any point in me voting at all. Ever since the 2008 presidential election, I have been reading in the newspapers about problems in our voting system. From the papers, I know our methods of counting votes are seriously flawed. Rewritten in this fashion, the paragraph moves from the general (“voting”) to the specific (“problems in our voting system”). The student author is gradually introducing her topic, the problems inherent in today’s electronic voting technology. Her opening paragraph still contains errors, but its organization is somewhat improved.

WINNING TACTICS FOR THE SAT

You now know the basic framework of the SAT. It’s time for the big question: How can you become a winner on the SAT?

• First, you have to decide just what winning is for you. For one student, winning means breaking 1500; for another, only a total score of 2100 will do. Therefore, the first thing you have to do is set your goal.

• Second, you must learn to pace yourself during the test. You need to know how many questions to attempt to answer, how many to spend a little extra time on, and how many simply to skip.

• Third, you need to understand the rewards of guessing—how educated guesses can boost your scores dramatically. Educated guessing is a key strategy in helping you to reach your goal.

Here are your winning tactics for the SAT.

TACTIC 1

Set your goal.

Before you begin studying for the SAT, you need to set a realistic goal for yourself. Here’s what to do.

1. Establish your baseline score. You need to know your math, critical reading, and writing scores on one actual PSAT or SAT to use as your starting point.

• If you have already taken an SAT, use your actual scores from that test.

• If you have already taken the PSAT but have not yet taken the SAT, use your most recent actual PSAT scores, adding a zero to the end of each score (55 on the PSAT = 550 on the SAT).

• If you have not yet taken an actual PSAT or SAT, do the following:

![]() Go to: http://www.collegeboard.org/practice/sat-practice-test and click on the link to either the online or printed version.

Go to: http://www.collegeboard.org/practice/sat-practice-test and click on the link to either the online or printed version.

OR

Get a hard copy of the College Board’s SAT preparation booklet from your school guidance office. (The online practice test and the test in the preparation booklet are the same.)

![]() Find a quiet place where you can work for 3¾ hours without interruptions.

Find a quiet place where you can work for 3¾ hours without interruptions.

![]() Take the SAT under true exam conditions:

Take the SAT under true exam conditions:

Time yourself on each section.

Take no more than a 2-minute break between sections.

After finishing three sections, take a 10-minute break.

Take another 10-minute break after section 7.

![]() Follow the instructions to grade the test and convert your total raw scores on each part to a scaled score.

Follow the instructions to grade the test and convert your total raw scores on each part to a scaled score.

![]() Use these scores as your baseline.

Use these scores as your baseline.

2. Look up the average SAT scores for the most recent freshman class at each of the colleges to which you’re applying. This information can be found online on the colleges’ web sites or in a college guide, such as Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges. You want to beat that average, if you can.

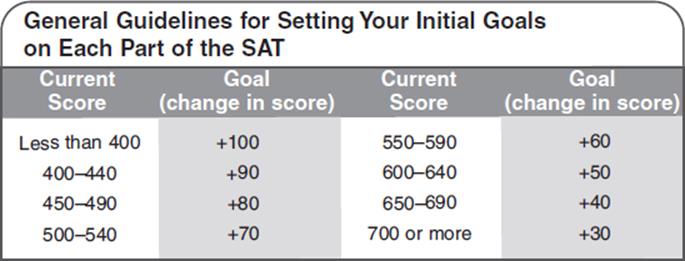

3. Now set your goals. Challenge yourself, but be realistic. If you earned 470 on the critical reading portion of the PSAT, for example, you might like to get 700 on the SAT, but that’s unrealistic. On the other hand, don’t wimp out. Aim for 550, not 490.

TACTIC 2

Know how many questions you should try to answer.

Why is it so important to set a goal? Why not just try to get the highest score you can by correctly answering as many questions as possible? The answer is that your goal tells you how many questions you should try to answer. The most common tactical error that students make is trying to answer too many questions. Therefore, surprising as it may be, the following statement is true for almost all students:

THE BEST WAY TO INCREASE YOUR SCORE ON THE SAT IS TO ANSWER FEWER QUESTIONS.

Why is slowing down and answering fewer questions the best way to increase your score on the SAT? To understand that, you first need to know how the SAT is scored. There are two types of scores associated with the SAT: raw scores and scaled scores. First, three raw scores are calculated—one for each part of the test. Each raw score is then converted to a scaled score between 200 and 800. On the SAT, every question is worth exactly the same amount: 1 raw score point. You get no more credit for a correct answer to the hardest math question than you do for the easiest. For each question that you answer correctly, you receive 1 raw score point. For each multiple-choice question that you answer incorrectly, you lose ¼ point. Questions that you leave out and grid-in questions you miss have no effect on your score. On each of the SAT’s three parts—Critical Reading, Math, and Writing Skills—the raw score is calculated as follows:

![]()

On every SAT, one math section has 20 multiple-choice questions. The questions in this section are presented in order of difficulty. Although this varies slightly from test to test, typically questions 1–6 are considered easy, questions 7–14 are considered medium, and questions 15–20 are considered hard. Even within the groups, the questions increase in difficulty: questions 7 and 14, for example, may both be ranked medium, but question 14 will definitely be harder than question 7. Of course, this depends slightly on each student’s math skills. Some students might find question 8 or 9 or even 10 to be easier than question 7, but everyone will find questions 11 and 12 to be harder than questions 1 and 2, and questions 19 and 20 to be harder than questions 13 and 14.

However, all questions have the same value: 1 raw score point. You earn 1 point for a correct answer to question 1, which might take you only 15 seconds to solve, and 1 point for a correct answer to question 20, which might take 2 or 3 minutes to solve. Knowing that it will probably take at least 10 minutes to answer the last 5 questions, many students try to race through the first 15 questions in 15 minutes or less and, as a result, miss many questions that they could have answered correctly, had they slowed down.

Suppose a student rushed through questions 1–15 and got 9 right answers and 6 wrong ones and then worked on the 5 hardest questions and answered 2 more correctly and 3 more incorrectly. His raw score would be 8¾: 11 points for the 11 correct answers minus 2¼ points for the 9 wrong answers. Had he gone slowly and carefully, and not made any careless errors on the easy and medium questions, he might have run out of time and not even answered any of the 5 hardest questions at the end. But if spending all 25 minutes on the first 15 questions meant that he answered 13 correctly, 2 incorrectly, and omitted 5, his raw score would have been 12½. If he had a similar improvement on the other math sections, his raw score would have been about 10 points higher, an increase of approximately 80 SAT points.

In this hypothetical scenario, a student increased his score significantly by answering fewer questions, but eliminating careless errors.

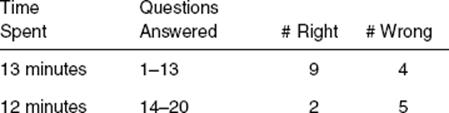

Now, let’s see how slowing down improved the scores of two actual students.

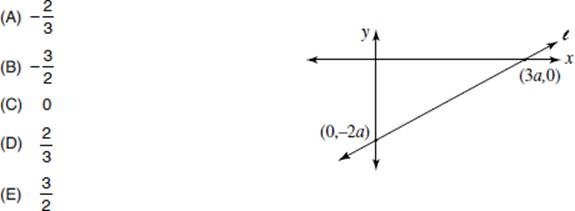

Student 1: John

Class standing: midrange

Grade point average: low 80s

Junior year SAT math score: 500

Goal: 570

Here’s how John did on the 25-minute math section with 20 questions.

Total: 11 right, 9 wrong

Raw score: 11 –2 ![]() = 8

= 8 ![]()

OUR ADVICE TO JOHN: Slow down. Don’t even try the hard problems at the end of the section. Spend all 25 minutes on the first 13 questions so that you avoid all careless mistakes.

John then took a practice SAT. On the 20-question math section, this is what happened:

Total: 12 right, 1 wrong

Raw score: 12 – ![]() = 11

= 11 ![]()

John’s raw score went up 3 points on just one section. He made similar improvements in the other two math sections, which resulted in a total increase of 8 raw score points, which raised his math scaled score by 70 points.

OUTCOME: With practice, John learned he could get the first 13 questions right in about 20 minutes, rather than 25. He used his extra 5 minutes to work on just two of the remaining questions in the section, selecting questions he had the best chance of answering correctly. As a result, his math score improved by more than 100 points!

Student 2: Mary

Class standing: top 10–15%

Grade point average: low 90s

Junior year SAT math score: 710

Junior year SAT reading score: 620

Goal: 1400 total in reading and math

PROBLEMS:

• slow reader

• raced through sentence completions to have more time for reading passages

• skimmed some reading passages instead of reading them

OUR ADVICE TO MARY: Slow down. On the reading section with two long passages, skip the 5-question passage and focus on reading the 10-question passage slowly and carefully.

OUTCOME: At first, Mary strongly resisted the idea of leaving out questions on the SAT, but she agreed to take our advice. When she retook the SAT her senior year, she answered just 59 reading questions and left out 8. Mary’s senior year reading score: 700.

What did John and Mary learn?

THE BEST WAY TO INCREASE YOUR SCORE ON THE SAT IS TO ANSWER FEWER QUESTIONS.

Many students prefer to think about the statement above paraphrased as follows:

THE BIGGEST MISTAKE MOST STUDENTS MAKE

IS TRYING TO ANSWER TOO MANY QUESTIONS.

So, how many questions should you try to answer?

First, set your goal based on your original scores. For example, if your original reading score was 540, your goal should be 610.

Next, look at an actual SAT score conversion table on the College Board’s web site or in its Official SAT Study Guide. Find the raw scores that correspond to your scaled score goals.

|

CRITICAL READING CONVERSION TABLE |

|

|

Raw Score |

Scaled Score |

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

|

51 |

640 |

|

50 |

630 |

|

49 |

620 |

|

48 |

620 |

|

47 |

610 |

|

46 |

610 |

|

45 |

600 |

|

44 |

590 |

|

43 |

580 |

|

42 |

580 |

You need a raw score of about 46 to reach your goal of 610 in critical reading. One way to do that would be to answer 46 questions correctly, and no questions wrong. But probably, even going slowly, you’ll miss a few, so answer about 6 more.

How many reading questions should you answer?

46 + 6 = 52

Remember, since you lose ¼ point for each question you answer incorrectly, you should answer 52 questions (omitting 15) so that, even if you miss 5, your raw score will still be 46.

![]()

How does that work out for each of the three reading sections?

On each 24-question critical reading section, aim to answer 19 questions and omit 5.

On the19-question critical reading section, answer 14 questions and omit 5.

19 + 19 + 14 = 52

TACTIC 3

Know how to pace yourself, section by section. Never get bogged down on any one question, and never rush.

Go quickly but carefully through the easy questions, slowly but steadily through the harder ones. Always keep moving.

Here is one pattern to follow:

|

20-Question Math Section (25 minutes total) |

|

|

Questions 1–5 |

1 minute each |

|

Questions 6–10 |

2 minutes each |

|

Questions 11–14 |

2½ minutes each |

|

Questions 15–20 |

Don’t even read them! |

Unless you are consistently getting at least 12 of the first 14 questions right, do not go any faster.

What if you finish all 14 questions in 22 or 23 minutes, and still have 2 or 3 minutes left? Here’s what to do. Take 30 seconds to read questions 15 and 16. Quickly decide which one you have the better chance of getting right or making an educated guess on. Use your remaining time on that one question.

What if you finish all 14 questions in just 20 minutes, and have 5 minutes left? You have time to answer two more questions at most. Do not automatically try to answer questions 15 and 16. Take a quick look at the remaining questions and pick the 2 questions that you like best. It’s like cherrypicking: pick the questions that look good to you. If you like geometry questions, try those. If you like algebra questions, try those instead. Skip around. Just be sure to mark your answer choices in the correct spots.

Of course, if you are very good at math and can consistently answer almost all of the questions correctly, your strategy might be to answer 18 of the 20 questions, or maybe even all 20. You shouldn’t, however, be answering all the questions if you are getting more than two or three incorrect; in that case, you should slow down and answer fewer questions and make fewer mistakes.

TACTIC 4

Know how to guess, and when.

The rule is, if you have worked on a problem and have eliminated even one of the choices, you must guess. This is what is called an educated guess. You are not guessing wildly, marking answers at random. You are working on the problem, ruling out answers that make no sense. The more choices you can rule out, the better your chance is of picking the right answer and earning one more point.

You should almost always be able to rule out some answer choices. Most math questions contain at least one or two answer choices that are absurd (for example, negative choices when you know the answer must be positive). In the critical reading section, once you have read a passage, you can always eliminate some of the answer choices. Cross out any choices that you know are incorrect, and go for that educated guess.

Unconvinced? If you are still not persuaded that educated guessing will work for you, turn to the end of this introduction for a detailed analysis of guessing on the SAT.

TACTIC 5

Keep careful track of your time.

Bring a watch. Even if there is a clock in the room, it is better for you to have a watch on your desk. Before you start each section, set your watch to 12:00. It is easier to know that a section will be over when your watch reads 12:25 than to have a section start at 9:37 and have to remember that it will be over at 10:02. Your job will be even easier if you have a digital stopwatch that you start at the beginning of each section; either let it count down to zero, or start it at zero and know that your time will be up after the allotted number of minutes.

TACTIC 6

Don’t read the directions or look at the sample questions.

For each section of the SAT, the directions given in this book are identical to the directions you will see on your actual exam. Learn them now. Do not waste even a few seconds of your valuable test time reading them.

TACTIC 7

Remember, each question, easy or hard, is worth just 1 point.

Concentrate on questions that don’t take you tons of time to answer.

TACTIC 8

Answer the easy questions first; then tackle the hard ones.

Because the questions in each section (except the passage-based reading questions) proceed from easy to hard, usually you should answer the questions in the order in which they appear.

TACTIC 9

Be aware of the difficulty level of each question.

Easy questions (the first few in each section or group) can usually be answered very quickly. Don’t read too much into them. On these questions, your first hunch is probably right. Difficult questions (the last few in a section or group) usually require a bit of thought. On these questions, be wary of an answer that strikes you immediately. You may have made an incorrect assumption or fallen into a trap. Reread the question and check the other choices before answering too quickly.

TACTIC 10

Feel free to skip back and forth between questions within a section or group.

Remember that you’re in charge. You don’t have to answer everything in order. You should skip the hard sentence completions at the end and go straight to the reading questions on the next page. You can temporarily skip a question that’s taking you too long and come back to it if you have time. Just be sure to mark your answers in the correct spot on the answer sheet.

TACTIC 11

In the critical reading and writing sections, read each choice before choosing your answer.

In comparison to math questions, which always have exactly one correct answer, critical reading questions are more subjective. You are looking for the best choice. Even if A or B looks good, check out the others; D or E may be better.

TACTIC 12

Fill in the answers on your answer sheet in blocks.

This is an important time-saving technique. For example, suppose that the first page of a math section has four questions. As you answer each question, circle the correct answer in your question book. Then, before going on to the next page, enter your four answers on your answer sheet. This is more efficient than moving back and forth between your question booklet and answer sheet after each question. This technique is particularly valuable on the passage-based reading sections, where entering your answer after each question may interrupt your train of thought about the passage.

CAUTION: When you get to the last two or three minutes of each section, enter your answers as you go. You don’t want to be left with a block of questions that you have answered but not yet entered when the proctor announces that time is up.

TACTIC 13

Make sure that you answer the question asked.

Sometimes a math question requires you to solve an equation, but instead of asking for the value of x, the question asks for the value of x2 or x – 5. Similarly, sometimes a critical reading question requires you to determine the LEAST likely outcome of an action; still another may ask you to find the exception to something, as in “The author uses all of the following EXCEPT.” To avoid answering the wrong question, circle or underline what you have been asked for.

TACTIC 14

Base your answers only on the information provided—never on what you think you already know.

On passage-based reading questions, base your answers only on the material in the passage, not on what you think you know about the subject matter. On data interpretation questions, base your answers only on the information given in the chart or table.

TACTIC 15

Remember that you are allowed to write anything you want in your test booklet.

Circle questions you skip, and put big question marks next to questions you answer but are unsure about. If you have time left at the end, you want to be able to locate those questions quickly to go over them. In sentence completion questions, circle or underline key words such as although, therefore, and not. In reading passages, underline or put a mark in the margin next to any important point. On math questions, mark up diagrams, adding lines when necessary. And, of course, use all the space provided to solve the problem. In every section, math, reading, and writing, cross out every choice that you know is wrong. In short, write anything that will help you, using whatever symbols you like. But remember: the only thing that counts is what you enter on your answer sheet. No one but you will ever see anything that you write in your booklet.

TACTIC 16

Be careful not to make any stray pencil marks on your answer sheet.

The SAT is scored by a computer that cannot distinguish between an accidental mark and a filled-in answer. If the computer registers two answers where there should be only one, it will mark that question wrong.

TACTIC 17

Don’t change answers capriciously.

If you have time to return to a question and realize that you made a mistake, by all means correct it, making sure you completely erase the first mark you made. However, don’t change answers on a last-minute hunch or whim, or for fear you have chosen too many A’s and not enough B’s. In such cases, more often than not, students change right answers to wrong ones.

TACTIC 18

Use your calculator only when you need to.

Many students actually waste time using their calculators on questions that do not require them. Use your calculator whenever you feel it will help, but don’t overuse it. And remember: no problem on the SAT requires lengthy, tedious calculations.

TACTIC 19

When you use your calculator, don’t go too quickly.

Your calculator leaves no trail. If you accidentally hit the wrong button and get a wrong answer, you have no way to look at your work and find your mistake. You just have to do it all over.

TACTIC 20

Remember that you don’t have to answer every question to do well.

You have learned about setting goals and pacing. You know you don’t have to answer all the questions to do well. It is possible to omit more than half of the questions and still be in the top half of all students taking the test; similarly, you can omit more than 40 questions and earn a top score. After you set your final goal, pace yourself to reach it.

TACTIC 21

Don’t be nervous: if your scores aren’t as high as you would like, you can always take the SAT again.

Relax. The biggest reason that some students do worse on the actual SAT than they did on their practice tests is that they are nervous. You can’t do your best if your hands are shaking and you’re worried that your whole future is riding on this one test. First of all, your SAT scores are only one of many factors that influence the admissions process, and many students are accepted at their first-choice colleges even if their SAT scores are lower than they had expected. But more important, because of Score Choice, you can always retake the SAT if you don’t do well enough the first or second time. So, give yourself the best chance for success: prepare conscientiously and then stay calm while actually taking the test.

_______________________

Now you have an overview of the general tactics you’ll need to deal with the SAT. In the next section, apply them: take the diagnostic test and see how you do. Then move on to Part Three, where you will learn tactics for handling each specific question type.

![]()

An Afterword: More on Guessing

![]()

Are you still worried about whether you should guess on the SAT? If so, read through the following analysis of how guessing affects your scores. The bottom line is, even if you don’t know the answer to a question, whenever you can eliminate one or more answer choices, you must guess.

In general, it pays to guess. To understand why this is so and why so many people are confused about guessing, you must consider what you know about how the SAT is scored.

Consider the following scenario. Suppose you work very slowly and carefully, answer only 32 of the critical reading questions (omitting 35), and get each of them correct. Your raw score will be converted to a scaled score of about 520. If that were the whole story, you should use the last minute of the test to quickly fill in an answer to each of the other questions. Because each question has 5 choices, you should get about one-fifth of them right. Surely, you would get some of them right—most likely about 7. If you did that, your raw score would go up 7 points, and your scaled score would then be about 560. Your critical reading score would increase 40 points because of 1 minute of wild guessing! Clearly, this is not what the College Board wants to happen. To counter this possibility, there is a so-called guessing penalty, which adjusts your scores for wrong answers and makes it unlikely that you will profit from wild guessing.

The penalty for each incorrect answer on the critical reasoning sections is a reduction of ¼ point of raw score. What effect would this penalty have in the example just discussed? Say that by wildly guessing you got 7 right and 28 wrong. Those 7 extra right answers caused your raw score to go up by 7 points. But now you lose ¼ point for each of the 28 problems you missed—a total reduction of ![]() or 7 points. As a result, you broke even: you gained 7 points and lost 7 points. Your raw score, and hence your scaled score, didn’t change at all.

or 7 points. As a result, you broke even: you gained 7 points and lost 7 points. Your raw score, and hence your scaled score, didn’t change at all.

Notice that the guessing penalty didn’t actually penalize you. It prevented you from making a big gain that you didn’t deserve, but it didn’t punish you by lowering your score. It’s not a very harsh penalty after all. In fairness, however, it should be pointed out that wild guessing could have lowered your score. It is possible that, instead of getting 7 correct answers, you were unlucky and got only 5 or 6, and as a result, your scaled score dropped from 520 to 510. On the other hand, it is equally likely that you would have been lucky and gotten 8 or 9 rather than 7 right, and that your scaled score would have increased from 520 to 530 or 540.

NOTE

On average, wild guessing does not affect your score on the SAT.

Educated guessing, on the other hand, can have an enormous effect on your score: it can increase it dramatically! Let’s look at what is meant by educated guessing and see how it can improve your score on the SAT.

Consider the following sentence completion question.

In Victorian times, countless Egyptian mummies were ground up to produce dried mummy powder, hailed by quacks as a near-magical ----, able to cure a wide variety of ailments.

(A) toxin

(B) diagnosis

(C) symptom

(D) panacea

(E) placebo

Clearly, what is needed is a word such as medicine—something capable of curing ailments. Let’s assume that you know that toxin means poison, so you immediately eliminate Choice A. You also know that, although diagnosis and symptom are medical terms, neither means a medicine or a cure, so you eliminate Choices B and C. You now know that the correct answer must be Choice D or E, but unfortunately you have no idea what either panacea or placebomeans.

You could guess, but you don’t want to be wrong; after all, there’s that penalty for incorrect answers. Then should you leave the question out? Absolutely not! You must guess! We’ll explain why and how in a moment, but first let’s look at one more example, this time a math question.

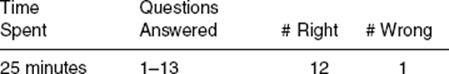

What is the slope of line ![]() in the figure to the right?

in the figure to the right?

Suppose that you have completely forgotten how to calculate the slope of a line, but you do remember that lines that go up ![]() have positive slopes and that lines that go down

have positive slopes and that lines that go down ![]() have negative slopes. Then you know the answer must be Choice D or E. What do you do? Do you guess and risk incurring the guessing penalty, or do you omit the question because you’re not sure which answer is correct? You must guess!

have negative slopes. Then you know the answer must be Choice D or E. What do you do? Do you guess and risk incurring the guessing penalty, or do you omit the question because you’re not sure which answer is correct? You must guess!

Suppose that you are still working slowly and carefully on the critical reading sections, and that you are sure of the answers to 32 questions. Of the 35 questions you planned to omit, there are 15 in which you are able to eliminate 3 of the choices, but you have no idea which of the remaining 2 choices is correct; and the remaining 20 questions you don’t even look at. You already know what would happen if you guessed wildly on those 20 questions—you would probably break even. But what about the 15 questions you narrowed down to 2 choices? If you guess on those, you should get about half right and half wrong. Is that good or bad? It’s very good! Assume you got 7 right and 8 wrong. For the 7 correct answers, you would receive 7 points, and for the 8 incorrect answers, you would lose ![]() = 2 points. This is a net gain of 5 raw score points, raising your critical reading SAT score from 520 to 560. It would be a shame to throw away those 40 points just because you were afraid of the guessing penalty.

= 2 points. This is a net gain of 5 raw score points, raising your critical reading SAT score from 520 to 560. It would be a shame to throw away those 40 points just because you were afraid of the guessing penalty.

At this point, many students protest that they are unlucky and that they never guess right. They are wrong. There is no such thing as a poor guesser, as we’ll prove in a minute. For the sake of argument, however, suppose you were a poor guesser, and that when you guessed on those 15 questions, you got twice as many wrong (10) as you got right (5). In that case you would have received 5 points for the correct ones and lost ![]() = 21/2 points for the incorrect ones. Your raw score would have increased by 2½ points, which would be rounded up to 3, and your scaled score would still have increased: from 520 to 540. Therefore, even if you think you’re a poor guesser, you should guess.

= 21/2 points for the incorrect ones. Your raw score would have increased by 2½ points, which would be rounded up to 3, and your scaled score would still have increased: from 520 to 540. Therefore, even if you think you’re a poor guesser, you should guess.

Actually, the real guessing penalty is not the one that the College Board uses to prevent you from profiting from wild guesses. The real guessing penalty is the one you impose on yourself by not guessing when you should.

Occasionally, you can even eliminate 4 of the 5 choices! Suppose that in the sentence completion question given above, you realize that you do know what placebo means, and that it can’t be the answer. You still have no idea about panacea, and you may be hesitant to answer a question with a word you never heard of; but you must. If, in the preceding math question, only one of the choices were positive, it would have to be correct. In that case, don’t omit the question because you can’t verify the answer by calculating the slope yourself. Choose the only answer you haven’t eliminated.

What if you can’t eliminate 3 or 4 of the choices? You should guess if you can eliminate even 1 choice. Assume that there are 20 questions whose answers you are unsure of. The following table indicates the most likely outcome if you guess at each of them.

On an actual test, there would be some questions on which you could eliminate 1 or 2 choices and others where you could eliminate 3 or even 4. No matter what the mix, guessing pays. Of course, if you can eliminate 4 choices, the other choice must be correct; it’s not a guess.

|

Most Likely Effect |

|||||

|

Number |

|||||

|

of choices |

Number |

Number |

Raw |

Scaled Score |

|

|

eliminated |

correct |

wrong |

score |

Verbal |

Math |

|

0 |

4 |

16 |

+0 |

+0 |

+0 |

|

1 |

5 |

15 |

+1.25 |

+10 |

+15 |

|

2 |

7 |

13 |

+3.75 |

+30 |

+40 |

|

3 |

10 |

10 |

+7.50 |

+50 |

+70 |

|

4 |

20 |

0 |

+20 |

+120 |

+150 |

The scoring of the math sections is somewhat different from the scoring of the critical reading. The multiple-choice math questions have the same ¼-point penalty for incorrect answers as do all the critical reading and writing skills questions. There is no penalty, however, on grid-in questions, so you can surely guess on those. Of course, because you can grid in any number from .001 to 9999, it is very unlikely that a wild guess will be correct. But, as you will see, sometimes a grid-in question will ask for the smallest integer that satisfies a certain property (the length of the side of a particular triangle, for example), and you know that the answer must be greater than 1 and less than 10. Then guess.

It’s time to prove to you that you are not a poor guesser; in fact, no one is. Take out a sheet of paper and number from 1 to 20. This is your answer sheet. Assume that for each of 20 questions you have eliminated three of the five choices (B, C, and E), so you know that the correct answer is either A or D. Now guess. Next to each number write either A or D. Tests 1, 2, and 3 list the order in which the first 20 A’s and D’s appeared on three actual SATs. Check to see how many right answers you would have had. On each test, if you got 10 out of 20 correct, your SAT score would have risen by about 60 points as a result of your guessing. If you had more than 10 right, add an additional 10 points for each extra question you got correct; if you had fewer than 10 right, subtract 10 points from 60 for each extra one you missed. If you had 13 right, your SAT score increased by 90 points; if you got only 7 right, it still increased by 30 points. Probably, for the three tests, your average number of correct answers was very close to 10. You couldn’t have missed all of the questions if you wanted to. You simply cannot afford not to guess.

You can repeat this experiment as often as you like. Ask a friend to write down a list of 20 A’s and D’s, and then compare your list and his. Or just go to the answer keys for the model tests in the back of the book, and read down any column, ignoring the B’s, C’s, and E’s.

Would you like to see how well you do if you can eliminate only two choices? Do the same thing, except this time eliminate B and D and choose A, C, or E. Give yourself 1 raw score point for each correct answer and deduct ¼ point for each wrong answer. Multiply your raw score by 8 to learn approximately how many points you gained by guessing.

A few final comments about guessing are in order.

• If it is really a guess, don’t agonize over it. Don’t spend 30 seconds thinking, “Should I pick A? The last time I guessed, I chose A; maybe this time I should pick D. I’m really not sure. But I haven’t had too many A answers lately; so, maybe it’s time.” STOP! A guess is just that— a guess.

• You can decide right now how you are going to guess on the actual SAT you take. For example, you could just always guess the letter closest to A: if A is in the running, choose it; if not, pick B, and so on. If you’d rather start with E, that’s OK, too.

• If you are down to two choices and you have a hunch, play it. But if you have no idea and it is truly a guess, do not take more than two seconds to choose. Then move on to the next question.

Answer key for guessing

|

TEST 1 |

|

|

1. A |

11. D |

|

2. D |

12. D |

|

3. D |

13. A |

|

4. A |

14. D |

|

5. A |

15. A |

|

6. D |

16. D |

|

7. D |

17. A |

|

8. A |

18. D |

|

9. A |

19. A |

|

10. A |

20. D |

|

TEST 2 |

|

|

1. D |

11. D |

|

2. A |

12. A |

|

3. D |

13. D |

|

4. A |

14. D |

|

5. D |

15. A |

|

6. A |

16. A |

|

7. A |

17. D |

|

8. D |

18. D |

|

9. A |

19. D |

|

10. A |

20. A |

|

TEST 3 |

|

|

1. A |

11. D |

|

2. D |

12. D |

|

3. D |

13. D |

|

4. A |

14. A |

|

5. D |

15. A |

|

6. D |

16. D |

|

7. D |

17. A |

|

8. A |

18. A |

|

9. A |

19. D |

|

10. D |

20. D |

|

TEST 4 |

|

|

1. A |

11. E |

|

2. C |

12. A |

|

3. A |

13. E |

|

4. C |

14. E |

|

5. E |

15. C |

|

6. E |

16. C |

|

7. C |

17. C |

|

8. A |

18. E |

|

9. E |

19. E |

|

10. C |

20. A |

|

TEST 5 |

|

|

1. C |

11. C |

|

2. A |

12. E |

|

3. A |

13. E |

|

4. A |

14. E |

|

5. C |

15. A |

|

6. E |

16. E |

|

7. A |

17. C |

|

8. C |

18. C |

|

9. C |

19. C |

|

10. C |

20. E |

|

TEST 6 |

|

|

1. C |

11. C |

|

2. C |

12. E |

|

3. E |

13. A |

|

4. E |

14. C |

|

5. A |

15. A |

|

6. A |

16. A |

|

7. C |

17. A |

|

8. E |

18. C |

|

9. E |

19. E |

|

10. A |

20. E |