Classic Human Anatomy in Motion: The Artist's Guide to the Dynamics of Figure Drawing (2015)

Chapter 5

Muscles of the Neck and Torso

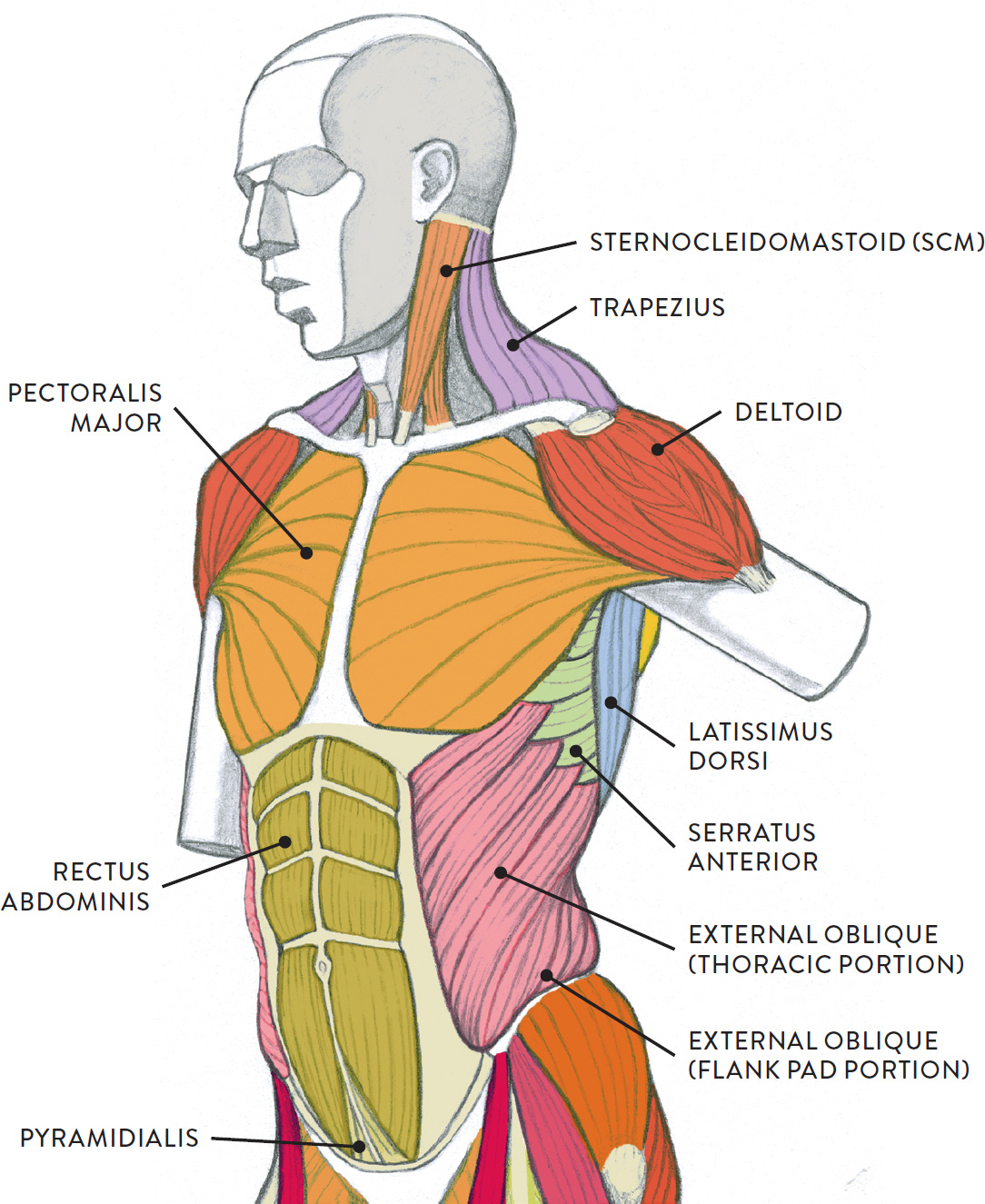

The muscles of the torso are interesting on many levels. First, unlike the muscles of the facial region, their shapes are somewhat recognizable on the surface. Second, some of the superficial muscles are already known by most people, though most likely by their common names: the shoulder muscle (trapezius), the chest or pectoral muscle (pectoralis major), the “abs” or “six-pack” (rectus abdominis), and the “flank pad” or “love handles” (external oblique). Third, the muscles of the torso do not move just the torso (vertebral column and rib cage) but also the shoulder girdle, which includes the scapula bones and clavicles, as well as the upper arms (humerus bones).

There are many ways to categorize the torso muscles. One way is to group them by their location on the anterior, lateral, and posterior regions of the body, but they can also be classified by anatomical regions (abdominal region, scapular region, pectoral region) or by their placement in relation to the surface (superficial layer, intermediate layer, deep layer).

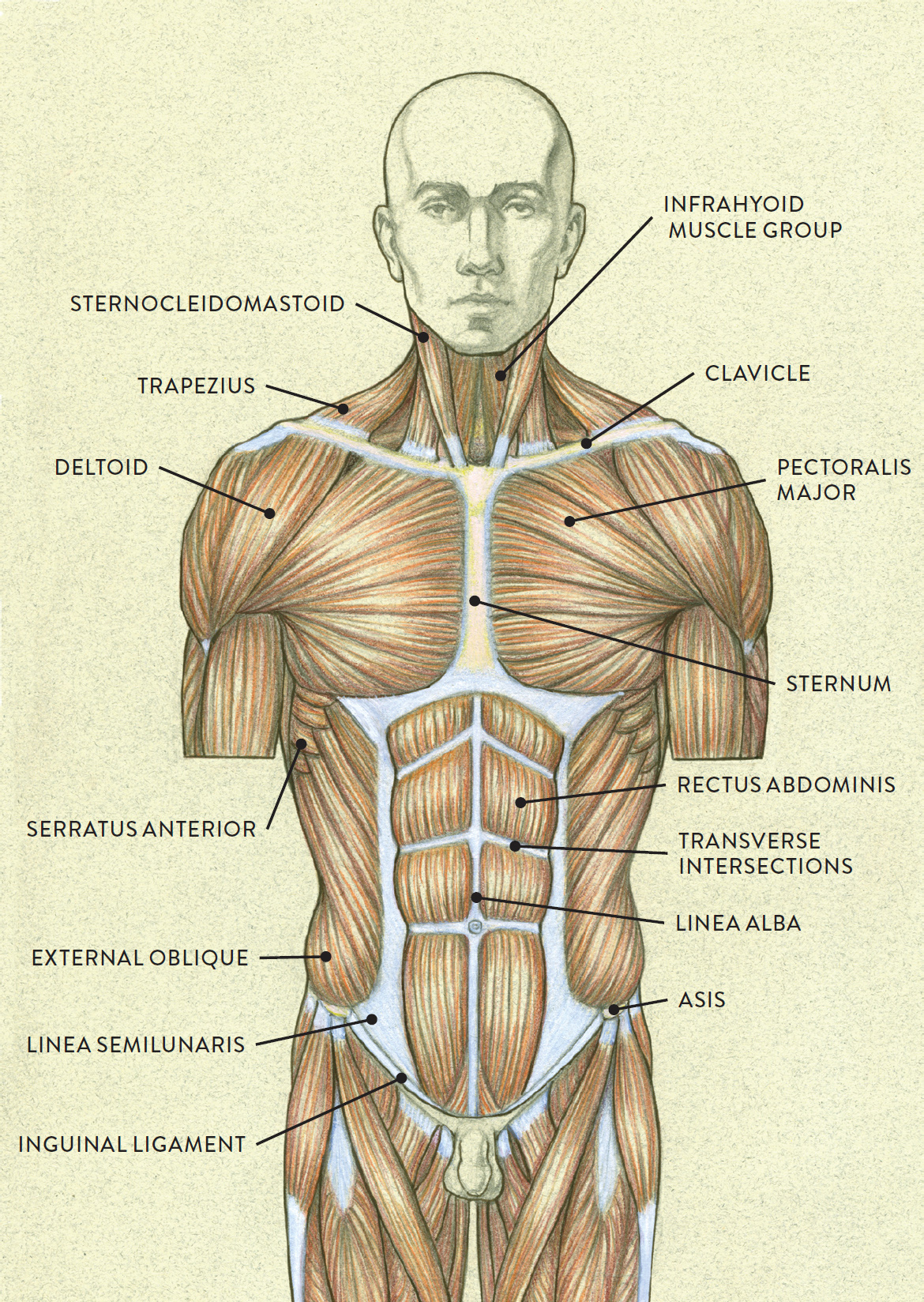

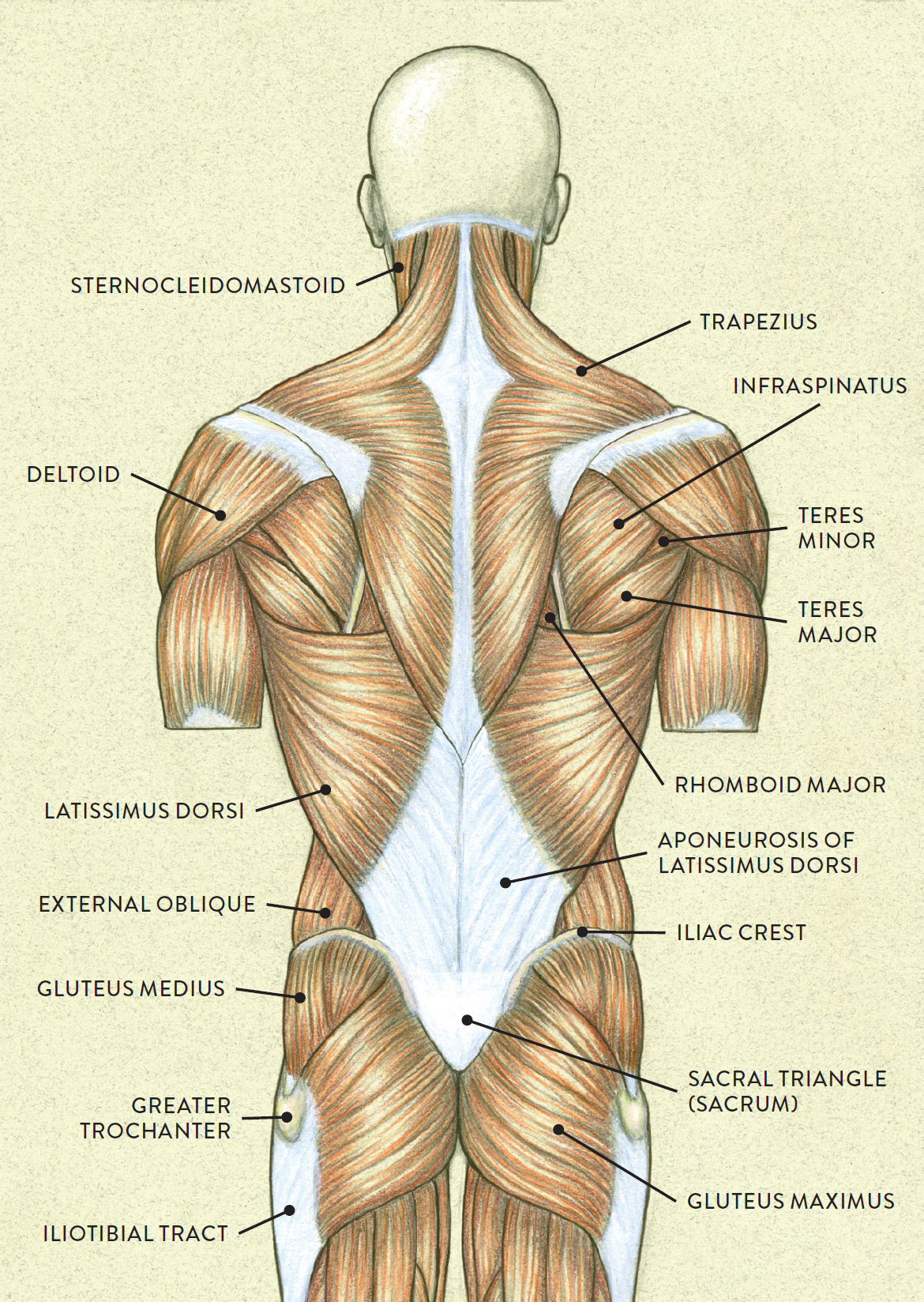

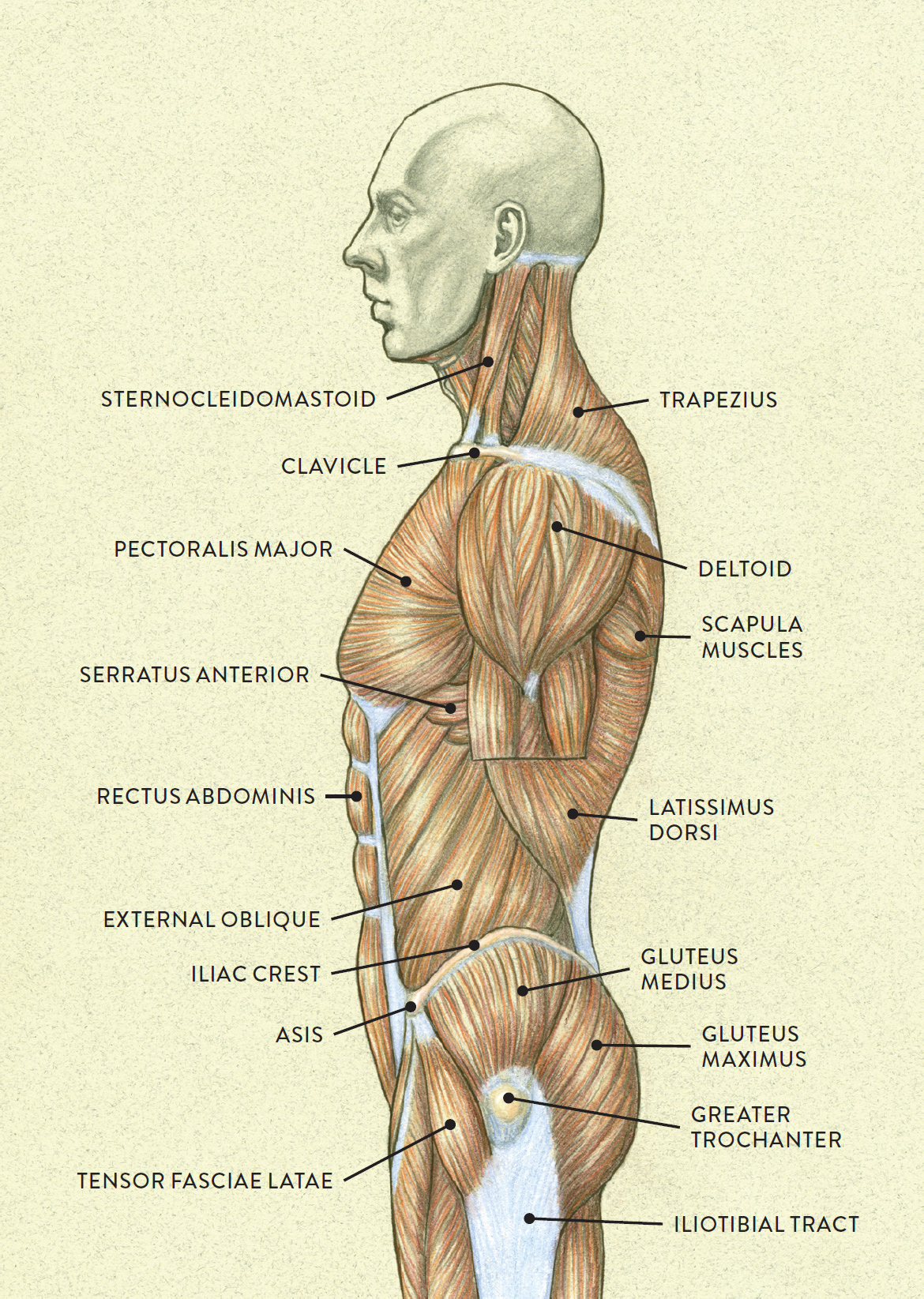

For learning purposes, a combination of systems is used in this chapter. First, let’s look at the torso muscles according to their placement on the body from front (anterior), back (posterior), and side (lateral) views, as shown in the following drawings.

MUSCLES OF THE TORSO—ANTERIOR VIEW

MUSCLES OF THE TORSO—POSTERIOR VIEW

MUSCLES OF THE TORSO—LATERAL VIEW

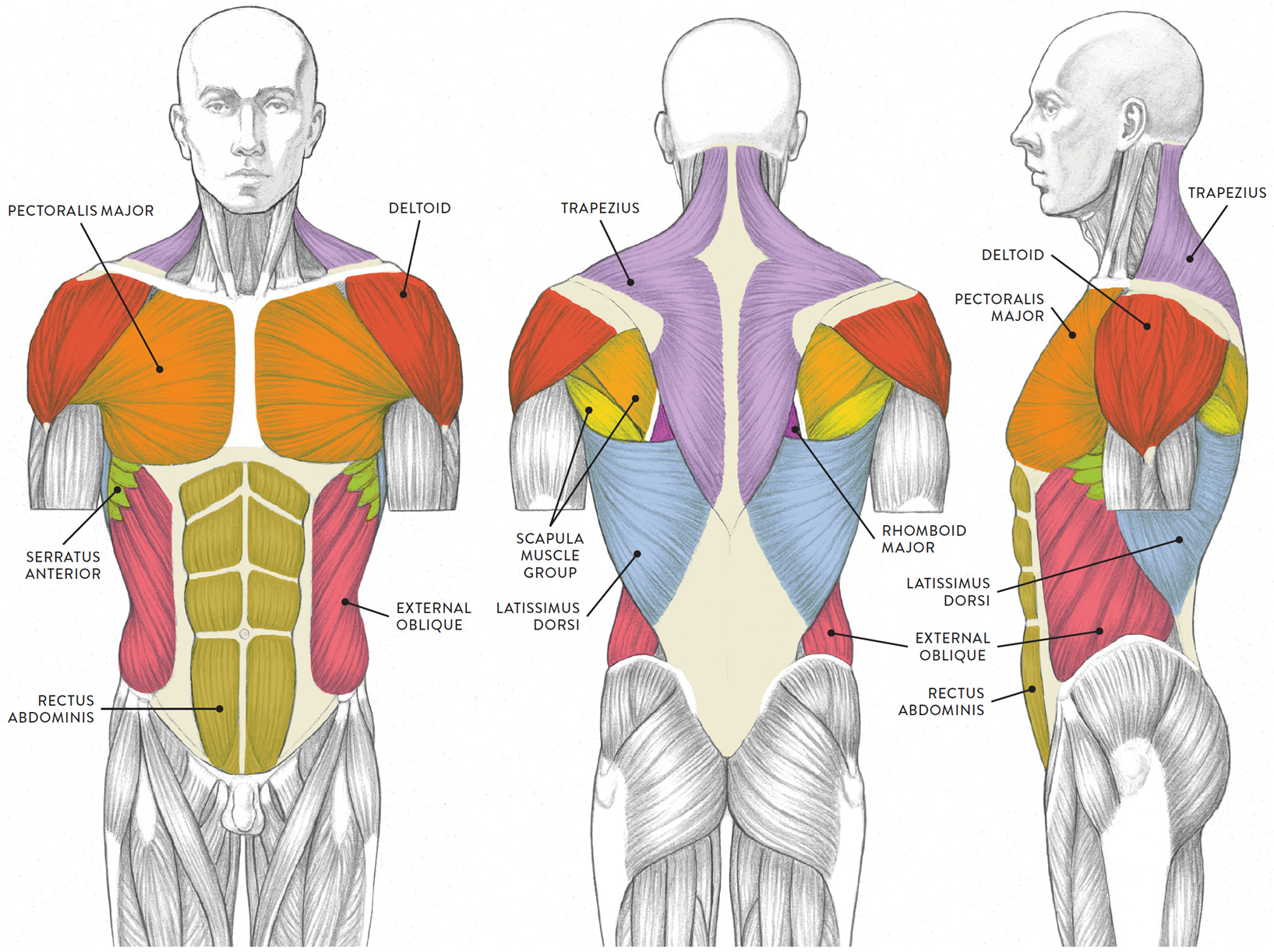

MUSCLES OF THE TORSO INDICATED BY COLOR

LEFT: Anterior view

CENTER: Posterior view

RIGHT: Lateral view

Names of Torso Muscles

The names of torso muscles provide clues to their location, shape, size, or the direction of their muscle fibers.

· Abdominis pertains to the abdominal region.

· Pectoralis pertains to the chest region.

· Anterior means “front.”

· Dorsi means “back.”

· Spinalis or spinatus indicates a location on or near a sharp bony projection, or spine.

· External means “outer.”

· Internal means “inner.”

· Major means “larger.”

· Minor means “smaller.”

· Rectus means “straight.”

· Oblique means “slanted” or “diagonal.”

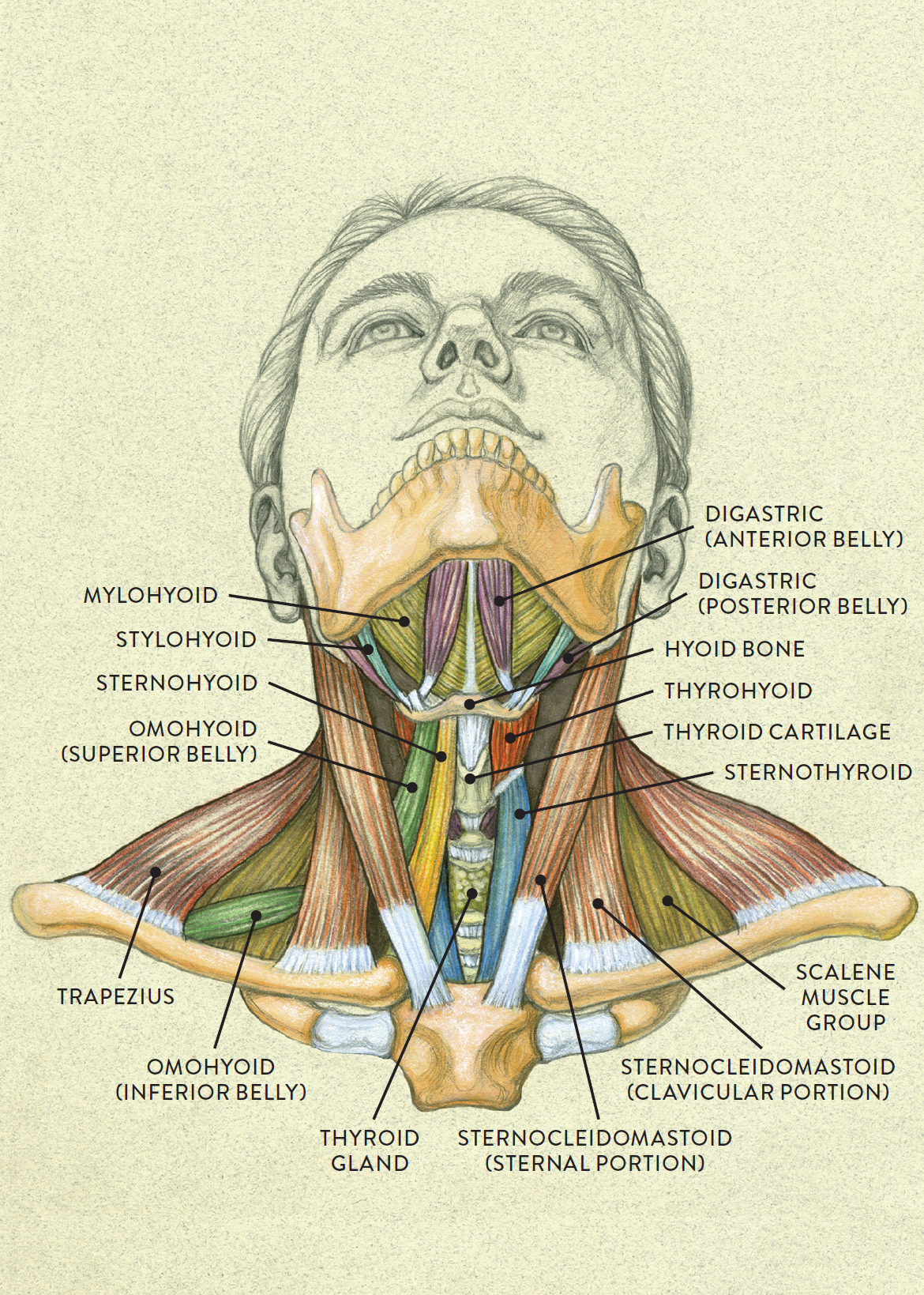

Muscles of the Neck

Before moving on to the individual muscle groups of the torso, let’s pause for a moment to look at the muscles of the neck—the transitional area between the head and torso. We already began doing so in the previous chapter, where I covered the suprahyoid muscles (this page) and the platysma (this page), which play roles in moving the jaw and in facial expressions. Here, we’ll focus briefly on the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and the infrahyoid muscle group. The major muscle of the back of the neck, the trapezius, is involved in movements of the scapula and is dealt with in the next section, on the muscles of the thorax.

The sternocleidomastoid (pron., STIR-no-KLIE-doe-MASS-toid) is a straplike muscle positioned on either side of the neck. This muscle begins at two different locations, one on the sternum (sternal portion) and the other on the clavicle (clavicular portion). The muscle fibers eventually merge into one shape, which inserts into the mastoid process (a small protrusion of bone on the skull behind the ear) and along a small ridge called the superior nuchal line of the occipital bone.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle helps bend and twist the head and neck in different directions, including flexion (bending the head forward), lateral flexion (bending the head sideways), and rotation (twisting the head left or right).

The anterior triangle of the neck region is located between the inside borders of the sternocleidomastoid muscles, the top portion of the sternum (manubrium), the hyoid bone, and the lower border of the digastric muscle (posterior belly). It contains several important structures, including the larynx (voice box), trachea (windpipe), and thyroid cartilage and gland. It is also the location of four straplike muscles collectively referred to as the infrahyoid muscles, which means the muscles below the hyoid bone. The four muscles are the superior belly of the omohyoid, the sternohyoid, the thyrohyoid, and the sternothyroid.

The infrahyoid muscles within the anterior triangle of the neck are rather hard to see on the surface form, but on some occasions, depending on the position of the neck, one or two muscles might be detected, as when the head bends back and the sternohyoid muscles create subtle vertical ridgelike forms on either side of the thyroid cartilage. The following drawing on this page shows the muscles of the neck and shoulder region. (For discussion of the muscles of the suprahyoid group—digastric, mylohyoid, and stylohyoid—see this page.)

MUSCLES OF THE NECK AND SHOULDER REGION

Anterior view of head tilting back

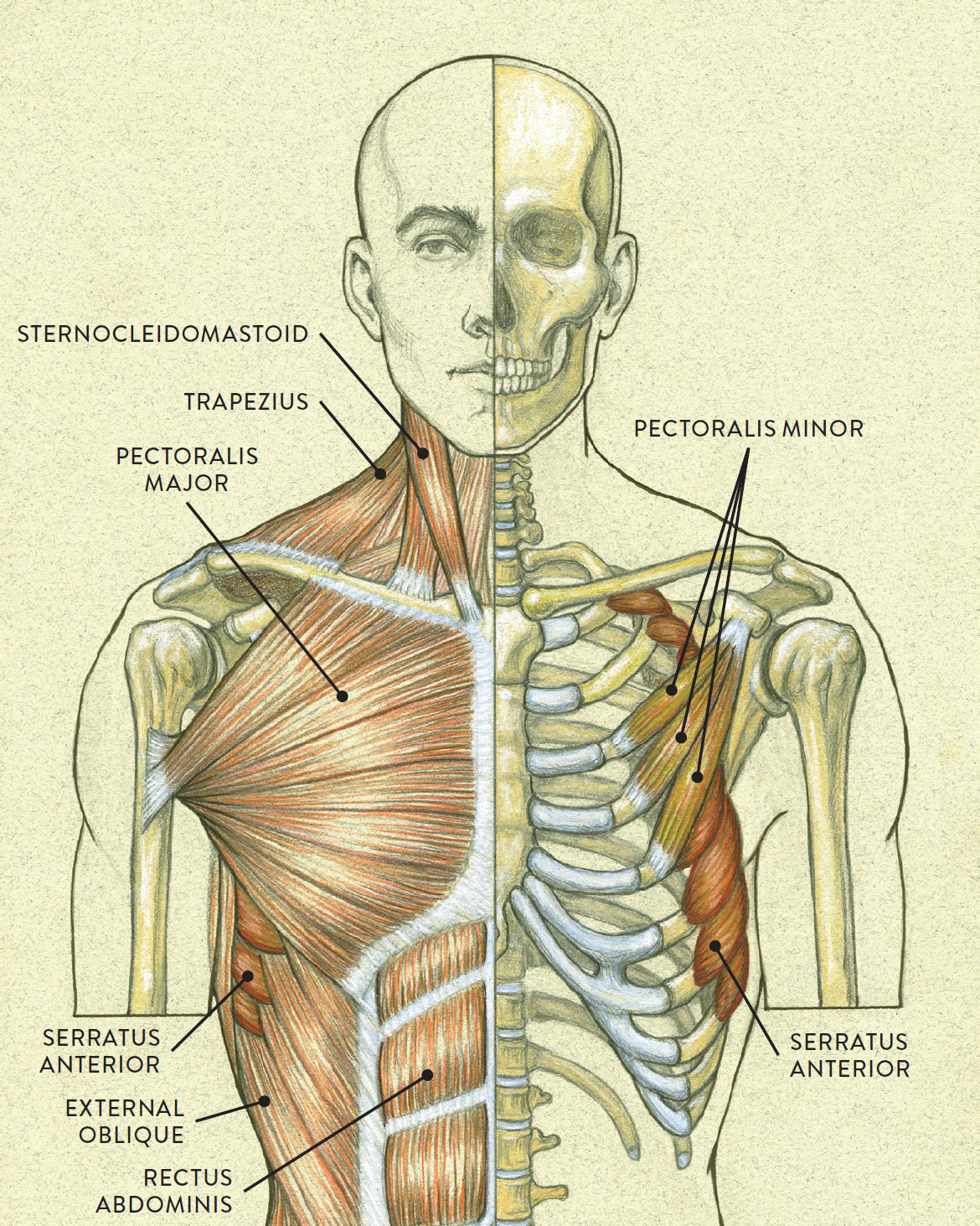

Muscles of the Thorax

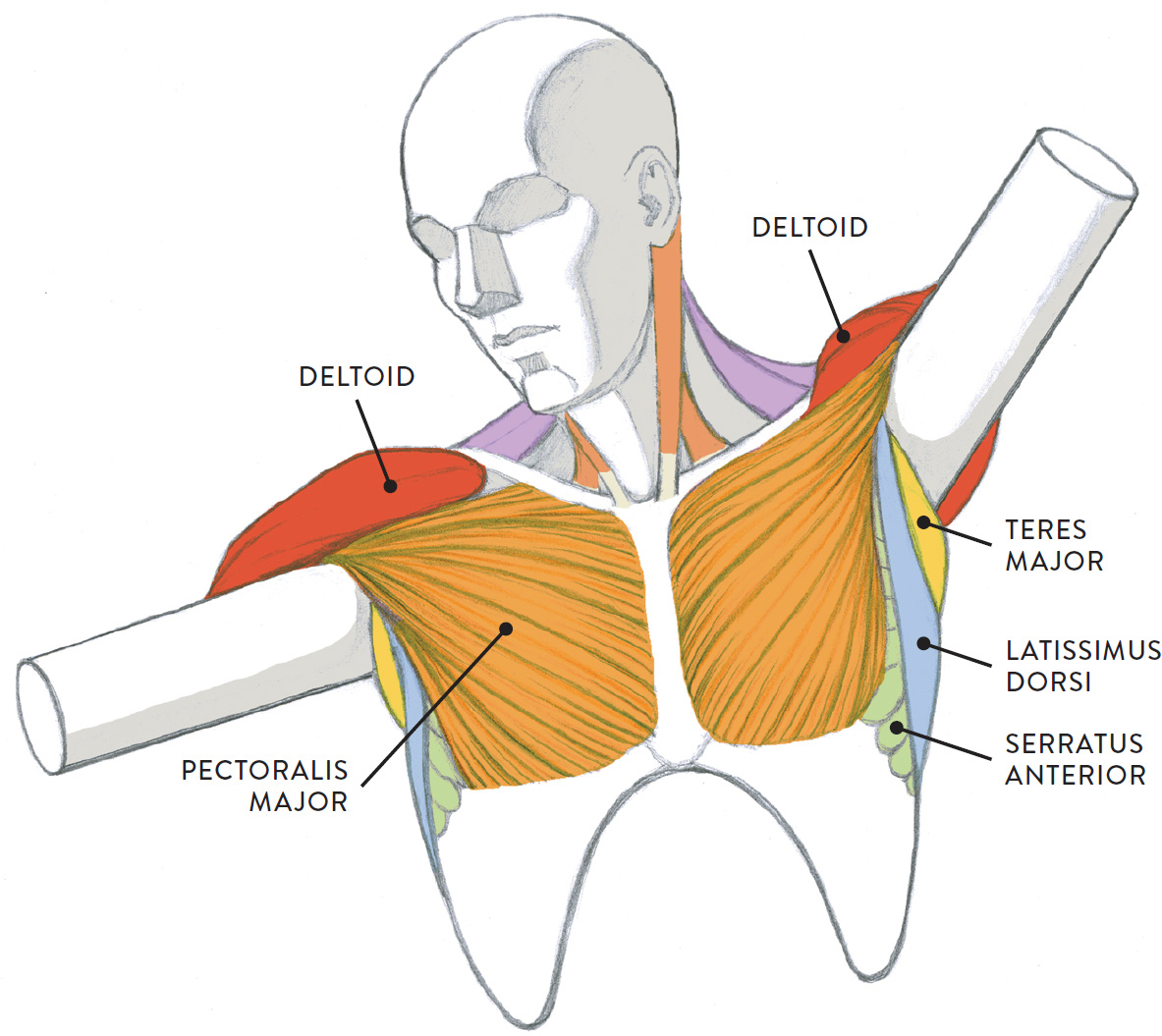

The thoracic muscles attach on the anterior and lateral regions of the thorax, or rib cage. They are the pectoralis major, the pectoralis minor, and the serratus anterior. The pectoralis major muscle helps move the humerus, and the pectoralis minor and the serratus anterior muscles help move the scapula bone.

THORACIC MUSCLES

The torso is divided in half to show the two layers of muscles in this region. The muscles on the left side are the superficial muscles (close to the surface), and the muscles on the right are positioned beneath the superficial muscles.

Anterior view

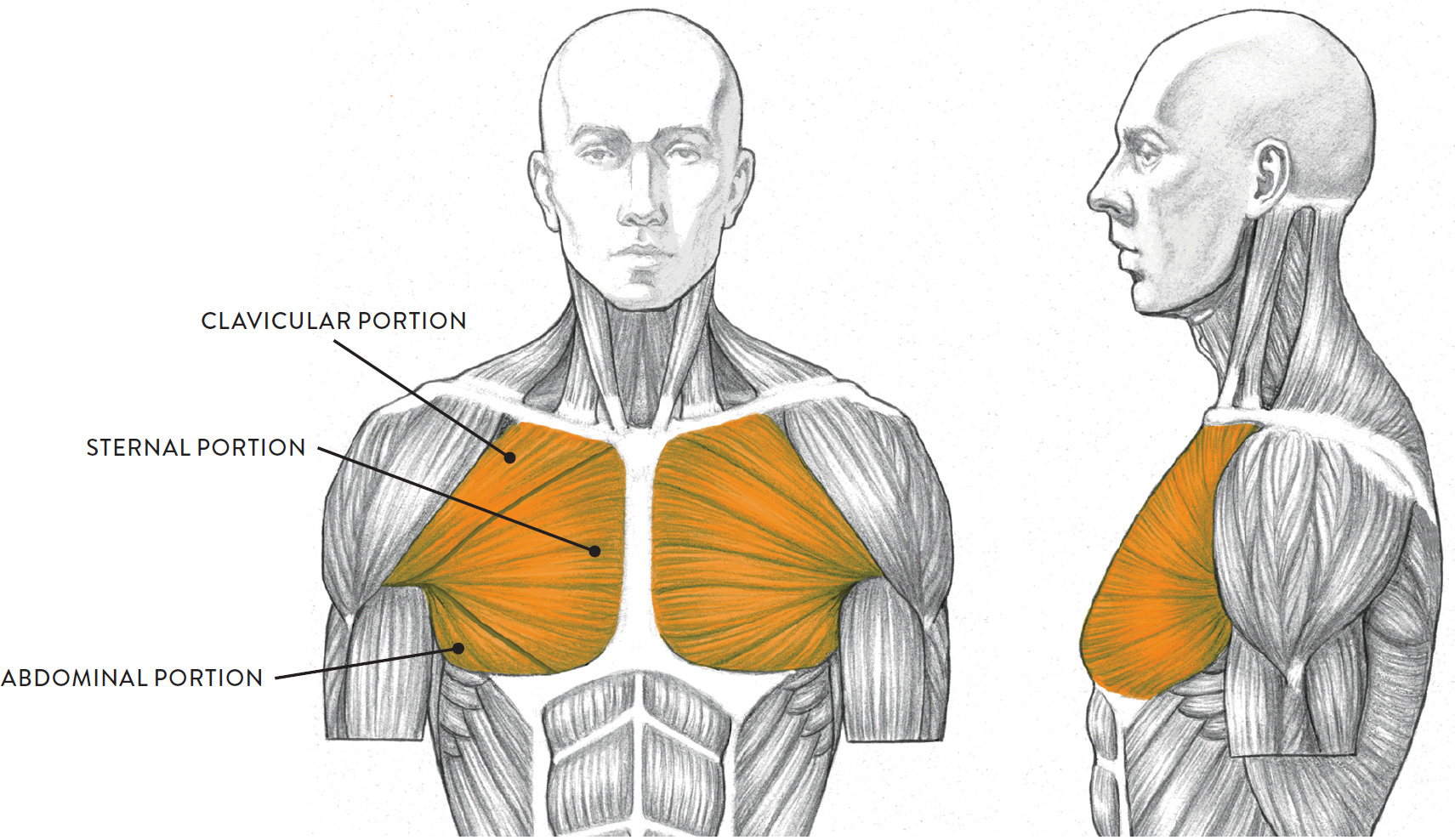

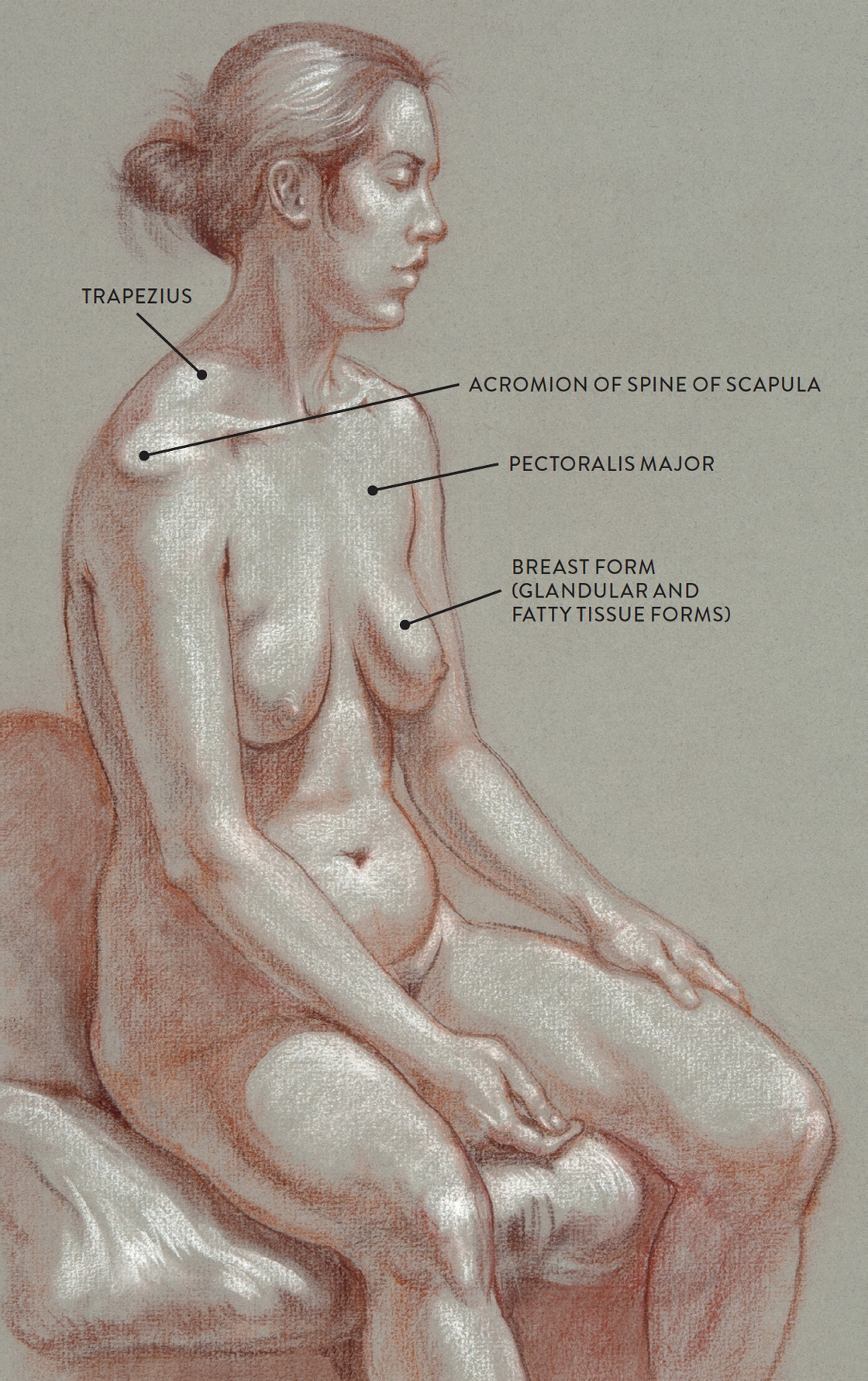

The pectoralis major (pron., PECK-tor-AL-liss MAY-jur) is a large, fan-shaped muscle that occupies the anterior region of the rib cage on either side of the sternum. This muscle has three portions: clavicular, sternal, and abdominal. The pectoralis major forms the anterior wall of the axillary region, or the armpit (see this page), which becomes apparent when the upper arm is positioned away from the torso. The breast form, a combination of glandular and fatty tissue forms, is attached to the fascia (a sheathing layer) that is situated over the pectoralis major muscle.

The clavicular portion begins on the clavicle; the sternal portion begins along the outer side of the sternum; and the abdominal portion begins on a small section of the abdominal sheath. The muscle fibers pull across the rib cage and converge to attach on the humerus (upper arm bone). When the upper arm is lifted away from the torso, the insertion of this muscle is seen more clearly.

The pectoralis major, shown in the next drawing in both anterior and lateral views, moves the humerus in various ways depending on which portion is contracting and which other muscles are assisting. The main actions are moving the humerus in a forward direction (flexion), moving the humerus from an overhead position and returning it to the side of the torso (adduction), and rotating the humerus in an inward direction (medial rotation).

PECTORALIS MAJOR

Torso, anterior (left) and lateral (right) views

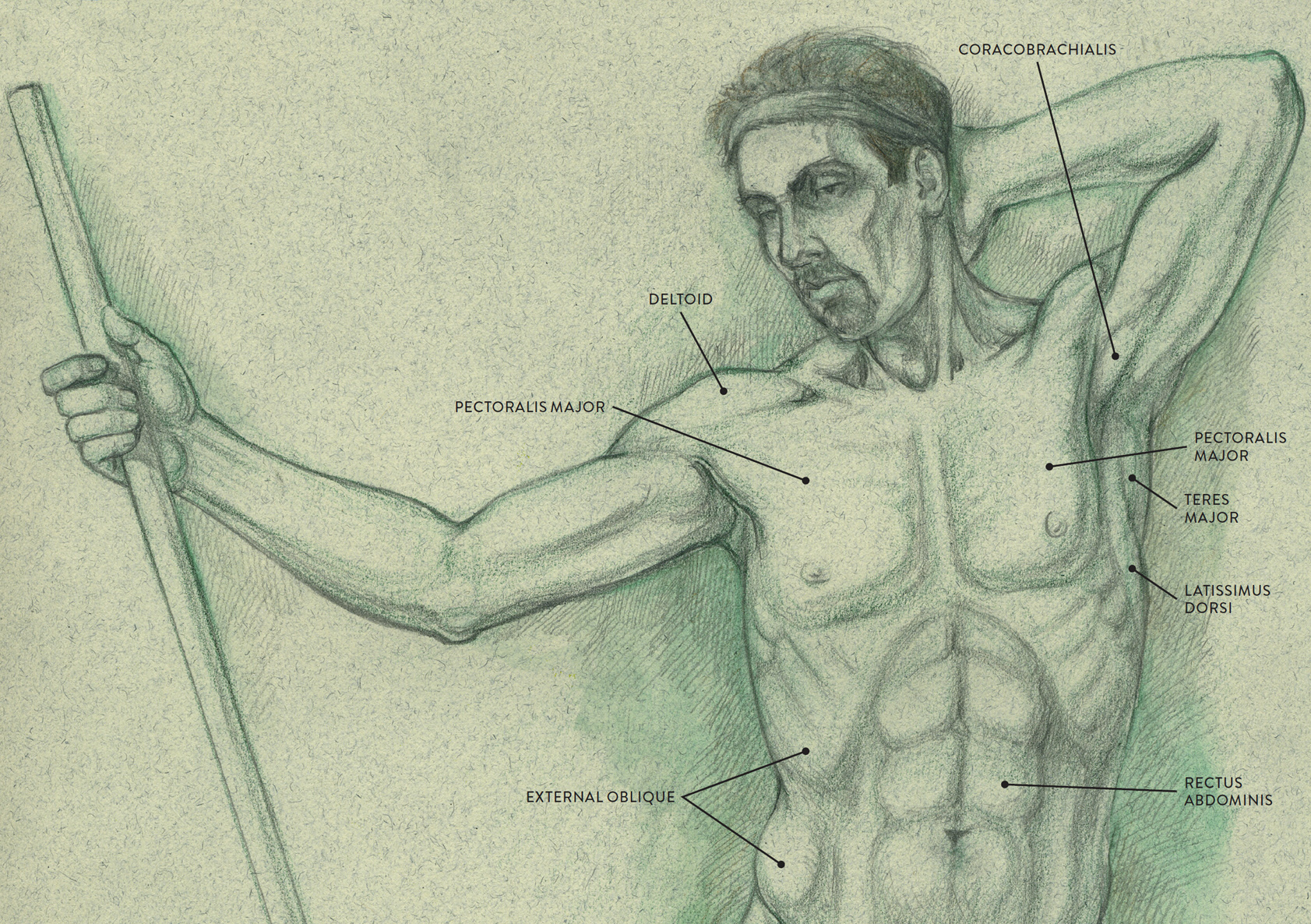

The following life study, Male Figure Holding a Staff, focuses on the pectoral area. With the arms positioned away from the torso, it is easy to see how the pectoralis major inserts into the humerus of the upper arm. The thick outer edge is the anterior wall of the axillary (armpit) region. The accompanying diagram reveals the actions of the muscles in this pose.

MALE FIGURE HOLDING A STAFF

Graphite pencil and watercolor pencil on light toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The next life study Seated Female Figure, shows the upper part of the pectoralis major positioned flat against the rib cage, with very little thickness. The soft-tissue forms of the breasts, consisting of glandular tissue (mammary glands) and fatty tissue, are anchored on the fascia sheathing that covers the pectoralis muscle. As the skin pulls over these forms (muscle and soft tissue) it creates a soft transition on the surface from the relative flatness of the upper rib cage to the rich spherical shapes of the breasts.

SEATED FEMALE FIGURE

Sanguine and brown pastel pencils and white chalk on toned paper.

The pectoralis minor (pron., PECK-tor-AL-liss MY-nor) consists of three muscle strips positioned beneath the pectoralis major. It is usually not detectible on the surface form. Each muscle strip of the pectoralis minor begins on a different rib (ribs 3 through 5). The muscle then inserts into the coracoid process (a small, beaklike bony protrusion) of the scapula. The pectoralis minor helps lower the shoulder blade in the action of depression of the scapula and moves the scapula in a forward direction in the protraction of the scapula.

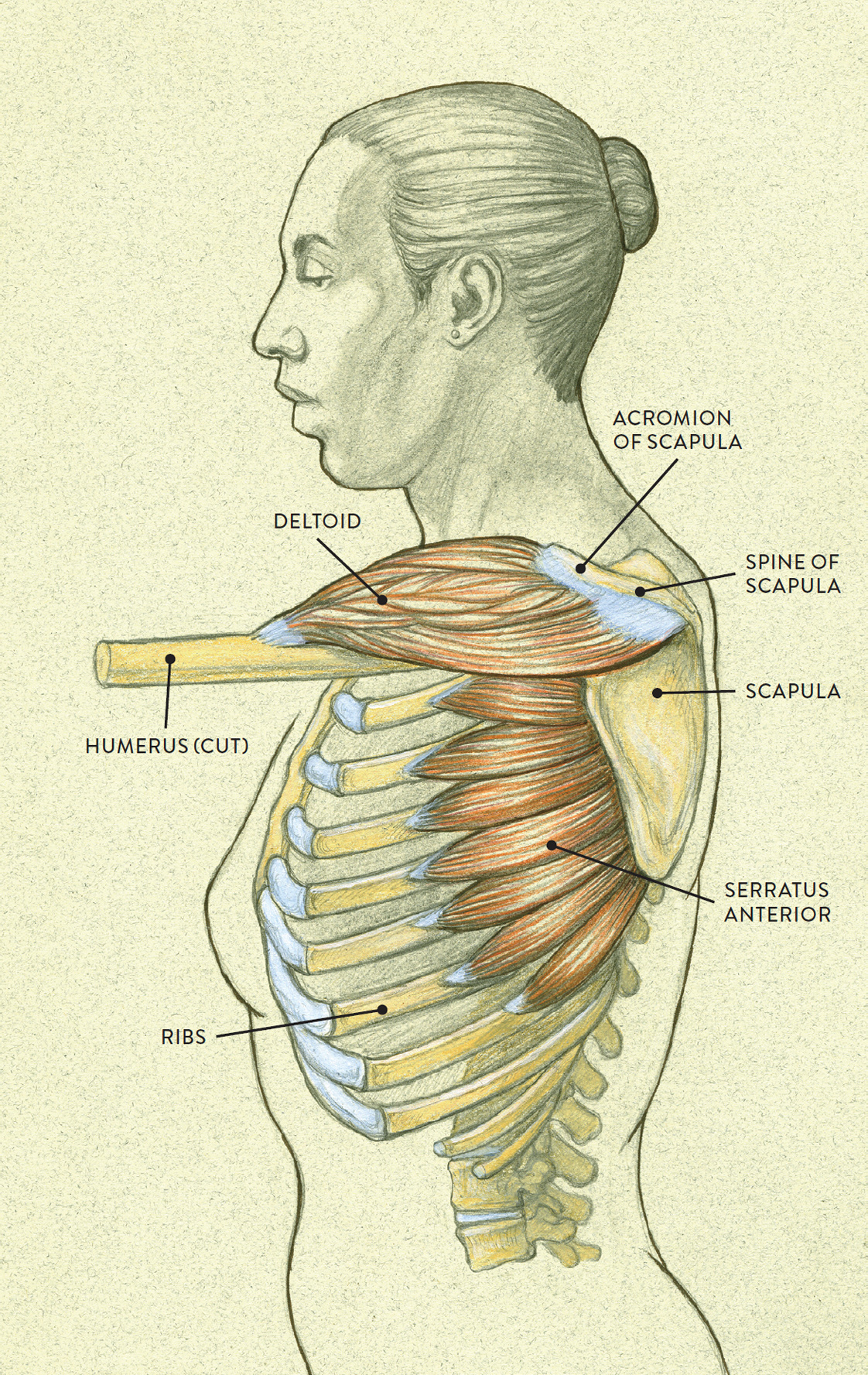

The serratus anterior (pron., sir-RAY-tus an-TEER-ee-or, sir-RAH-tus an-TEER-ee-or, or SIR-ah-tus an-TEER-ee-or) is a fan-shaped muscle consisting of eight or nine separate muscle digitations (finger-like shapes) located on the lateral region (outer side) of the rib cage. Each of these elongated muscle strips attaches on a separate rib, beginning with the first rib, and wraps around the side of the rib cage to insert into the medial (inner) border of the scapula. The serratus anterior is mostly hidden by the pectoralis major and the latissimus dorsi muscles, but the lower three or four digitations can be visible on the surface, appearing as small, riblike forms between the outer edge of the pectoralis major and the outer edge of the latissimus dorsi.

The main actions of the serratus anterior are the protraction and upward rotation of the scapula. Protraction of the scapula is the action of moving the scapula in a forward direction and occurs when the arm is reaching forward in front of the torso, as shown in the following drawing. Upward rotation is the tilting the scapula in a upward direction and occurs when the arm is raised overhead.

SERRATUS ANTERIOR, WITH DELTOID MUSCLE

Lateral view of torso with humerus lifted in a forward direction

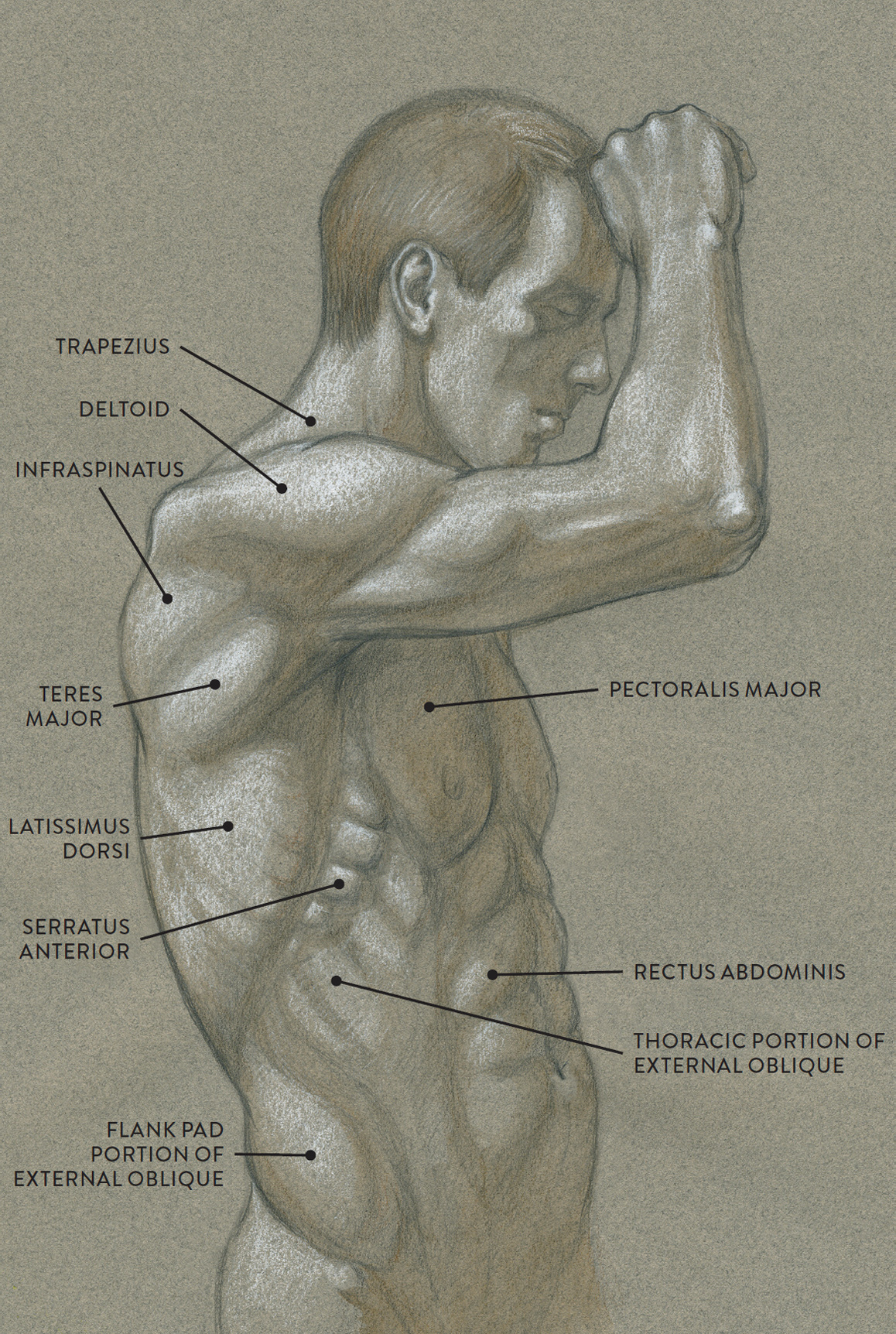

The life study Male Figure Lifting His Right Arm, Side View, right, shows a man raising his arm to expose the muscles more clearly. Between the rich outer edge of the latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major appear some small riblike forms that are the partly exposed shapes of the serratus anterior.

MALE FIGURE LIFTING HIS RIGHT ARM—SIDE VIEW

Graphite pencil, watercolor wash, and white chalk on toned paper.

The Abdominal Muscle Group

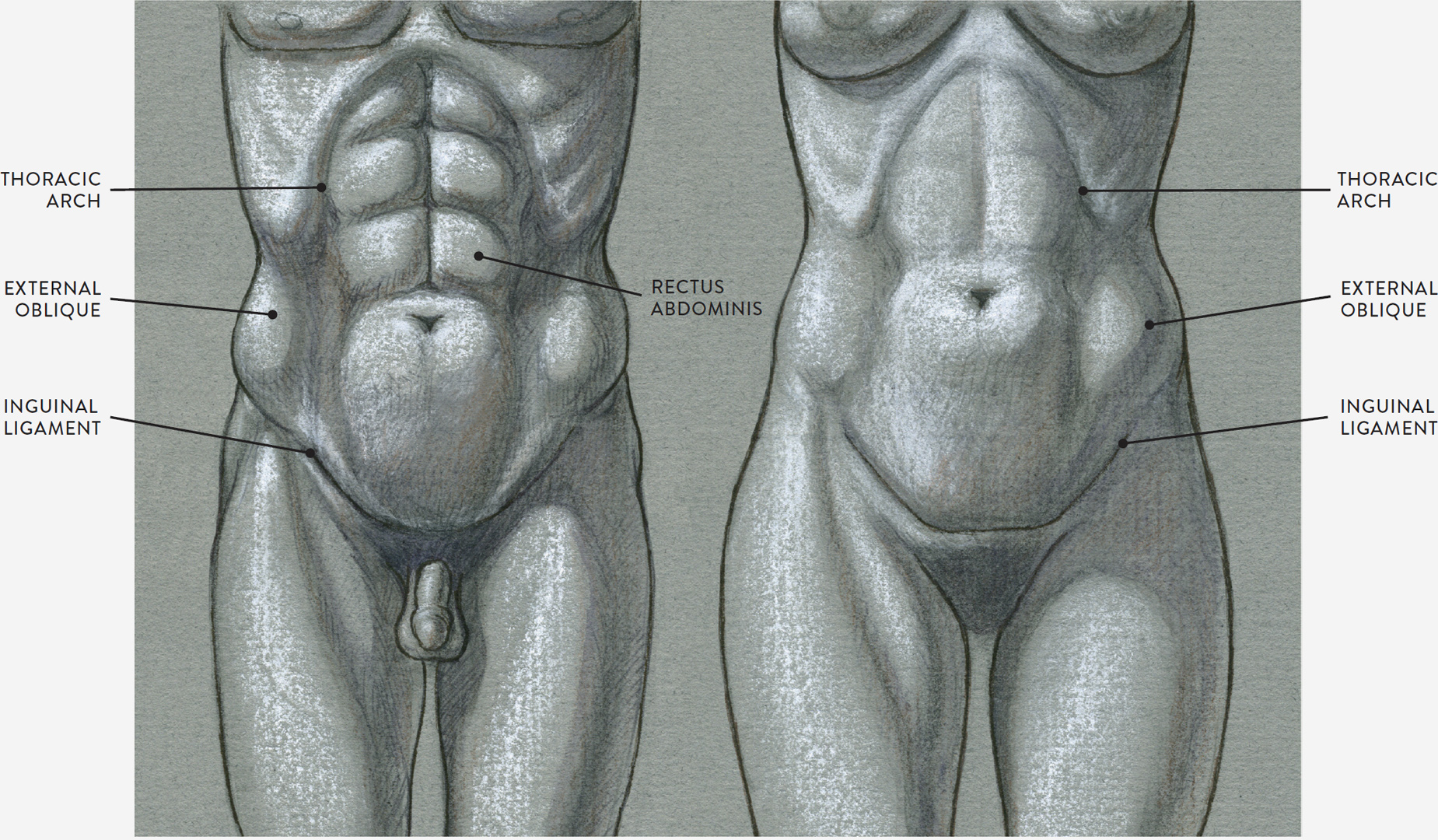

Occupying the anterior and lateral regions of the abdominal area of the torso are three layers of muscles: The superficial muscle layer contains the external oblique and rectus abdominis—the two abdominal muscles seen on the surface form. The intermediate layer contains the internal oblique, and the deep layer contains the transversus abdominis. The abdominal muscle group helps move the vertebral column and rib cage in the actions of forward bending (flexion), side bending (lateral flexion) and rotation, as well as causing the compression of the abdominal wall. Muscles belonging to each of the layers are shown in the following drawing.

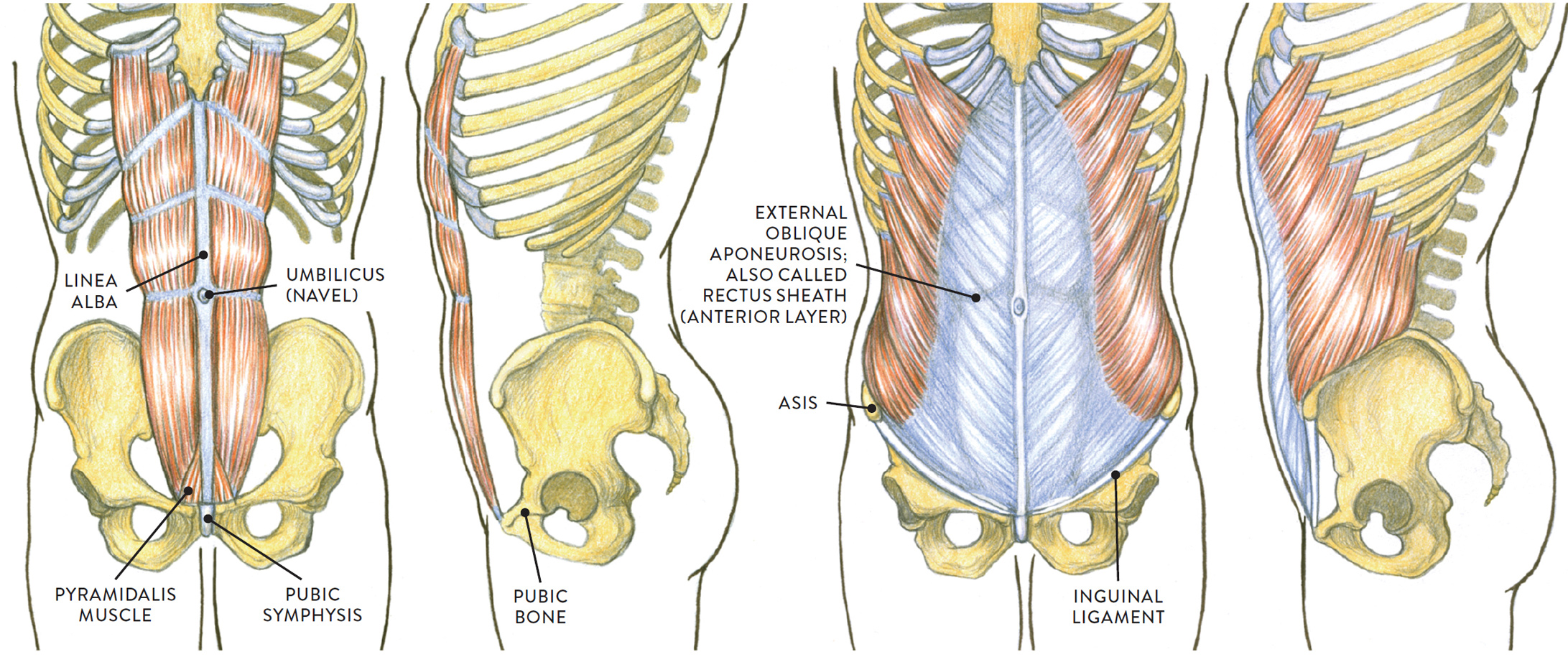

ABDOMINAL MUSCLE GROUP

Anterior and lateral regions of the torso

LEFT: Rectus abdominis (superficial layer)

RIGHT: External oblique (superficial layer)

LEFT: Internal oblique (intermediate layer)

RIGHT: Transversus abdominis (deep layer)

Three abdominal muscles—the transversus abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique—are layered atop each other on the lateral region of the lower torso; their muscle fibers run in different directions, producing a twisting or swiveling action of the torso when these muscles contract. Each of these muscles has its own large tendinous sheathing that continues across the abdomen to attach into the linea alba—a fibrous vertical form that attaches from the base of the sternum to the pubic bone of the pelvis. The layered sheathings act as a fibrous sleeve in which the rectus abdominis muscle (located in the anterior region of the lower torso) is encased. When the anterior (front) layer of this sheath is removed, the rectus abdominis muscle is exposed to reveal its eight muscle segments.

The various layers of sheathing of the abdomen have different names, which can cause confusion when studying this region. Adding to the potential difficulty, the anterior layer (positioned over the rectus abdominis muscle) is referred to by several names: the external oblique aponeurosis, or the rectus sheath (anterior layer), or sometimes the abdominal sheathing. The sheathing of the internal oblique is usually called the internal oblique aponeurosis, and the sheathing of the tranversus abdominis is called the rectus sheath (posterior layer), because it is positioned beneath the rectus abdominis muscle.

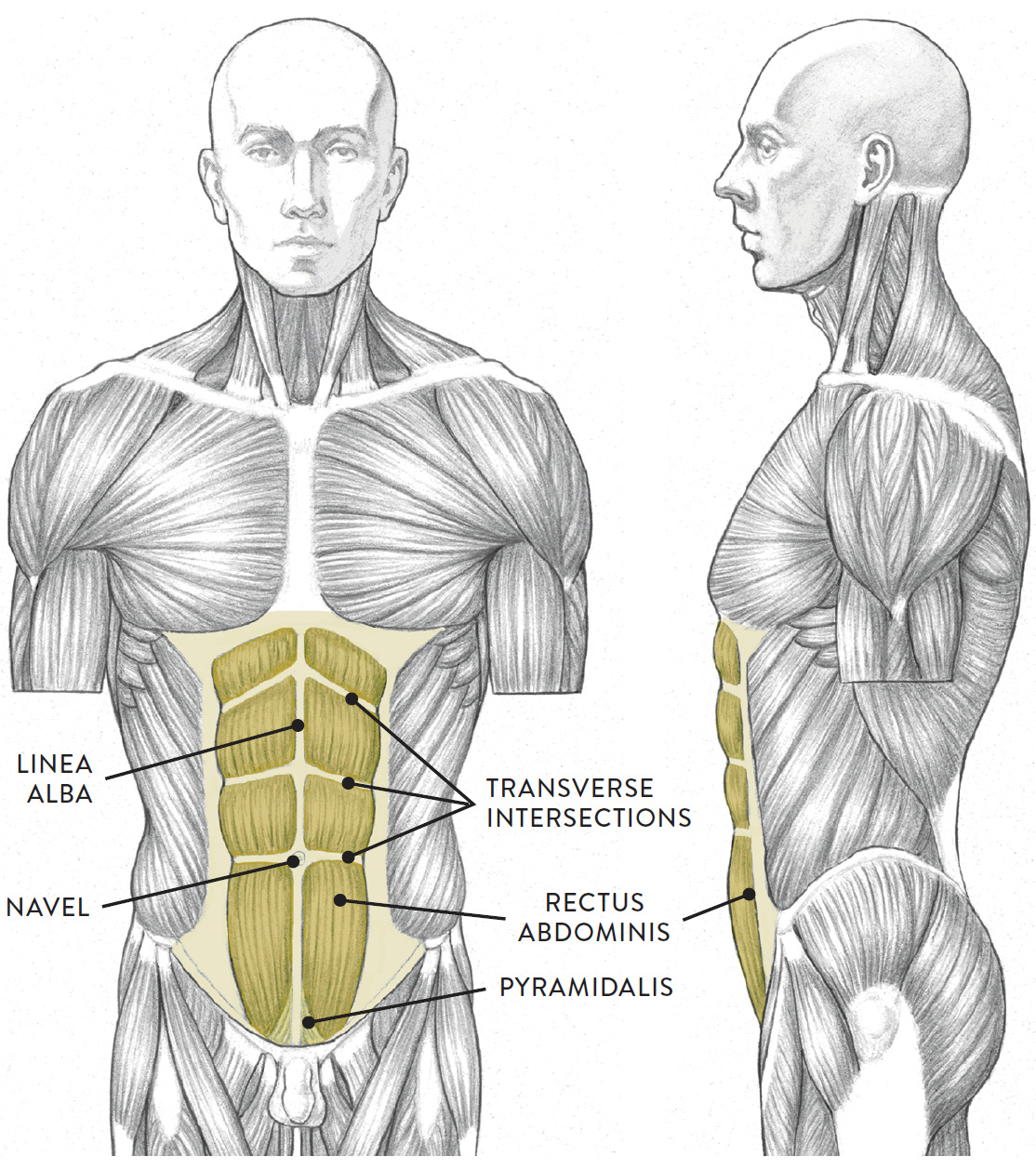

The rectus abdominis (pron., RECK-tuss ab-DOM-ih-niss) muscle occupies the front portion of the torso in the abdomen region. The muscle is divided by a vertical fibrous line called the linea alba (“white line”) and three horizontal fibrous lines called the transverse lines. The rectus abdominis is commonly known as the “six-pack,” because the muscle is divided into six sections above the navel, which appear as six small forms on the surface of some muscularly defined torsos. Below the navel, the muscle is divided into an additional two segments (more on some individuals), but a layer of fatty tissue usually softens the lower two segments into one shape. Differences between the rectus abdominis as it appears on males and females are examined in the sidebar on this page.

The rectus abdominis begins on the pubic bone and pulls straight up to attach into the xiphoid process of the sternum and the costal cartilages of the fifth, sixth, and seventh ribs. The muscle helps bend the torso forward in the movement known as the flexion of the vertebral column. It also helps raise the body from a supine position to an upright sitting position.

The pyramidalis (pron., purr-RAM-ah-DAY-liss or PEER-ah-mah-DALL-liss) is a very small triangular muscle located at the base of the rectus abdominis. It is hard to detect on the surface form because its muscle fibers blend with those of the rectus abdominis. The muscle begins on the pubic symphysis of the pelvis and inserts into the lower portion of the linea alba. The pyramidalis does not help move any bones. Its main function is to help tense the linea alba. Both the rectus abdominis and the pyramidalis are shown in the following drawing.

RECTUS ABDOMINIS, WITH PYRAMIDALIS

Superficial layer of abdominal muscle group, anterior region of torso

Torso, anterior (left) and lateral (right) views

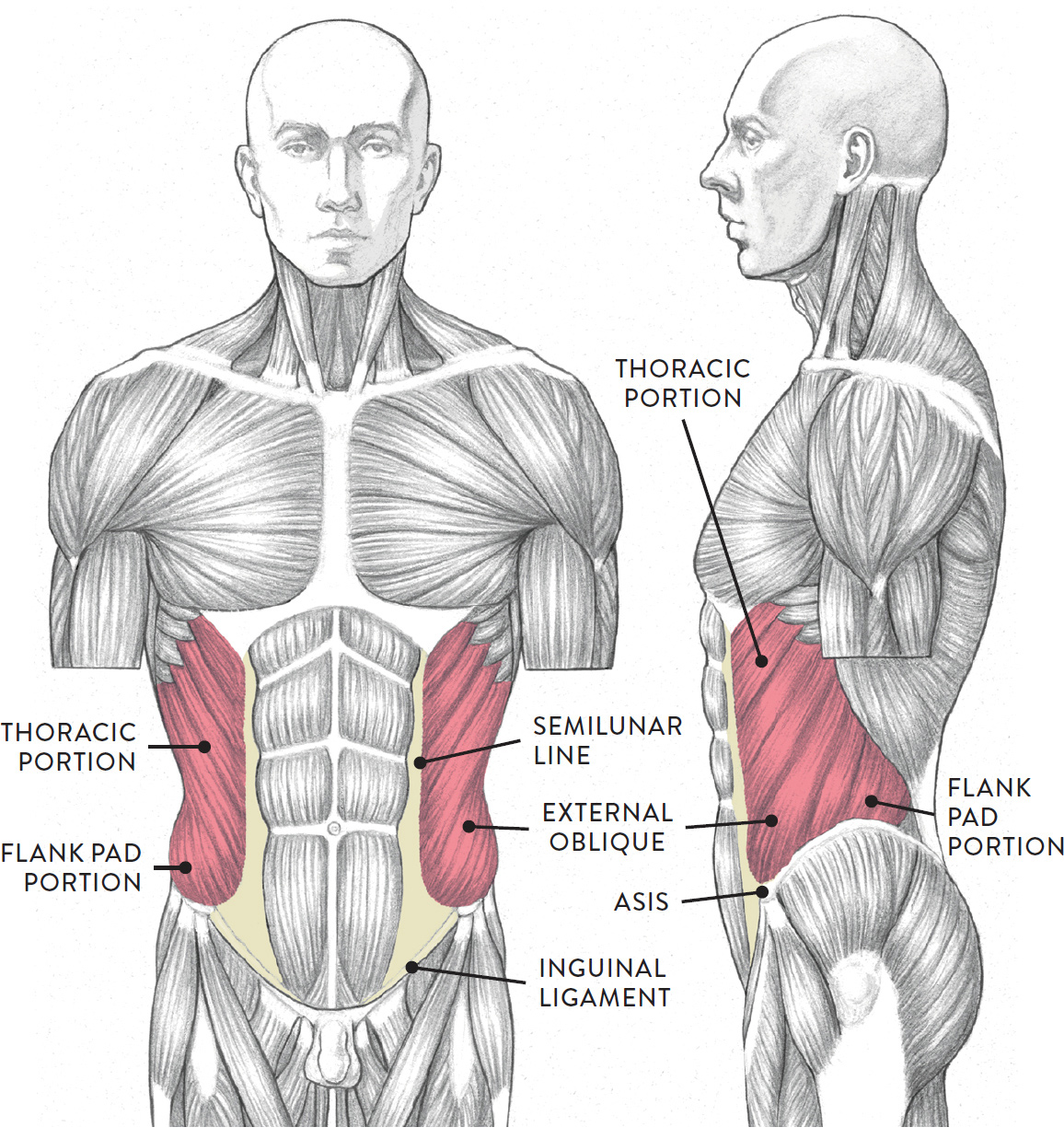

The external oblique (pron., ex-STER-nal oh-BLEEK) is located on the lateral (side) portion of the torso. The muscle consists of eight elongated muscle digitations and is divided into two portions: the thoracic portion and the abdominal portion, also called the flank pad. The thoracic portion hugs the rib cage like a girdle and is hard to detect on the surface except in muscularly defined torsos. The individual muscle strips of the thoracic portion begin on the ribs and appear to interweave with the muscle digitations of the serratus anterior. The flank pad portion is more noticeable as a bulbous shape beginning below the waistline. At the bottom portion, its muscle fibers anchor along the upper rim of the pelvis (iliac crest), slightly cascading over it near the ASIS of the pelvis. While this is a muscle form, it is usually enhanced with a layer of fatty tissue, giving it a rounded, more prominent shape. Artists use this form as an important landmark in torso studies.

EXTERNAL OBLIQUE

Superficial layer of abdominal muscle group, lateral region of torso

Torso, anterior (left) and lateral (right) views

The external oblique begins on the lower eight ribs (ribs 5 through 12) and inserts into the iliac crest of the pelvis, the inguinal ligament, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique and linea alba. When the external oblique contracts, it helps bend the torso in a forward direction (flexion) as well as sideways (lateral flexion). It also helps move the torso in a twisting action (rotation). The flank pad portion can stretch or compress, especially when the torso bends at the side in a dynamic way.

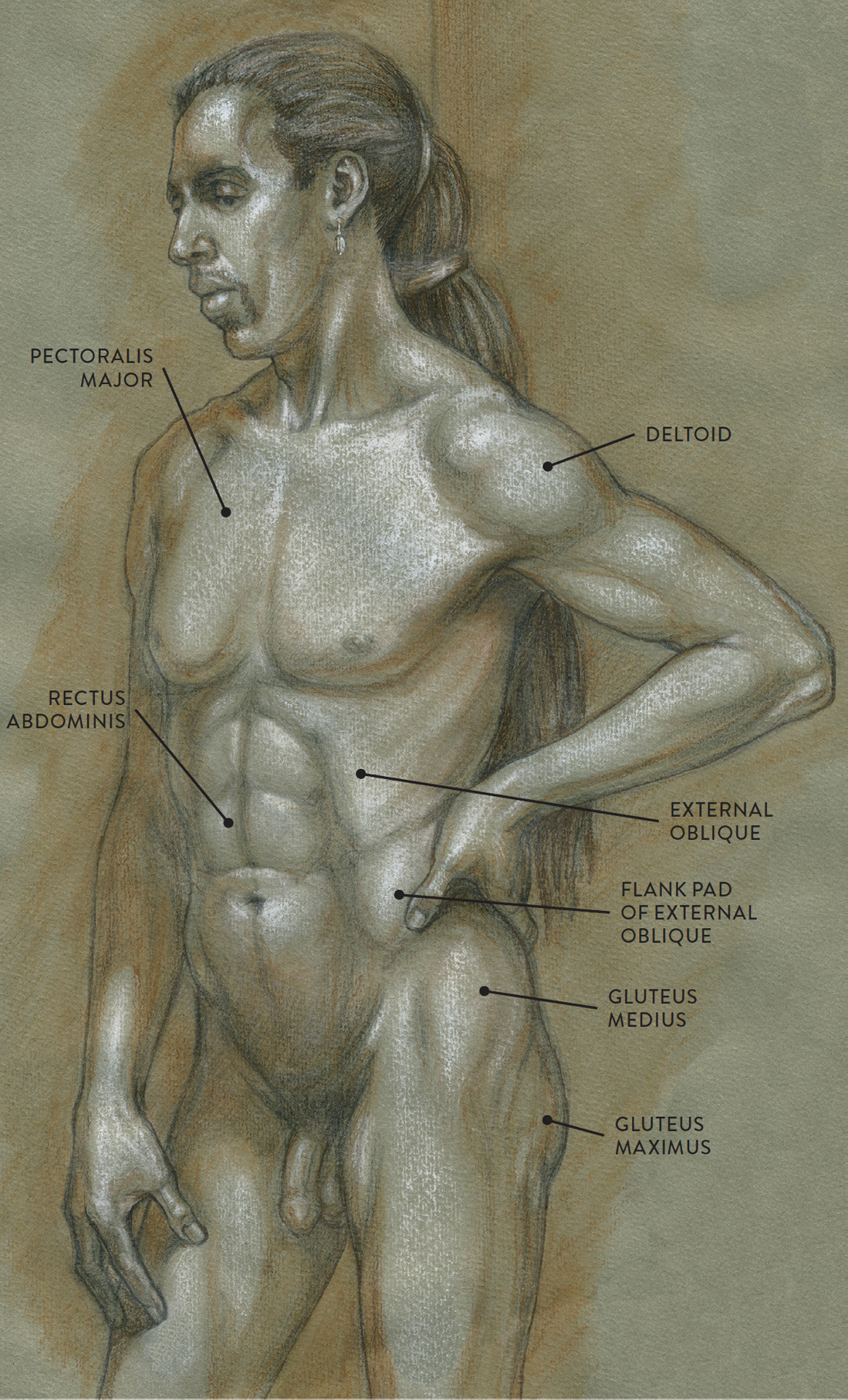

In the life study Male Figure with Left Hand on Hip, we see the abdominal region (rectus abdominis and the external oblique), along with the pectoralis major of the thoracic group. The diagram accompanying the drawing reveals the actions of the muscles in this pose.

MALE FIGURE WITH LEFT HAND ON HIP

Graphite pencil, brown ink, watercolor wash, and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

Rectus Abdominis—Male versus Female

The drawings here present idealized versions of male and female torsos. The male torso shows the classic muscle divisions (“six-pack”) of the rectus abdominis; the female torso, usually having more subcutaneous tissue, is softer in appearance, with an overall shape similar to that of a violin. There are, however, many variations among real people, male and female. Women who do intensive weight training can develop six-packs, while the rectus abdominis in men can be obscured with excess fatty tissue, creating what is colloquially known as a beer belly.

DIFFERENCES IN THE ABDOMINAL REGION—MALE AND FEMALE

LEFT: Male torso, anterior view

Muscle shapes are more apparent on the surface

RIGHT: Female torso, anterior view

Muscles are covered with a thicker layer of subcutaneous tissue, softening the surface form

LEFT: A muscular male abdomen is similar to a six-pack.

RIGHT: The female abdomen is generally softer and violin-shaped.

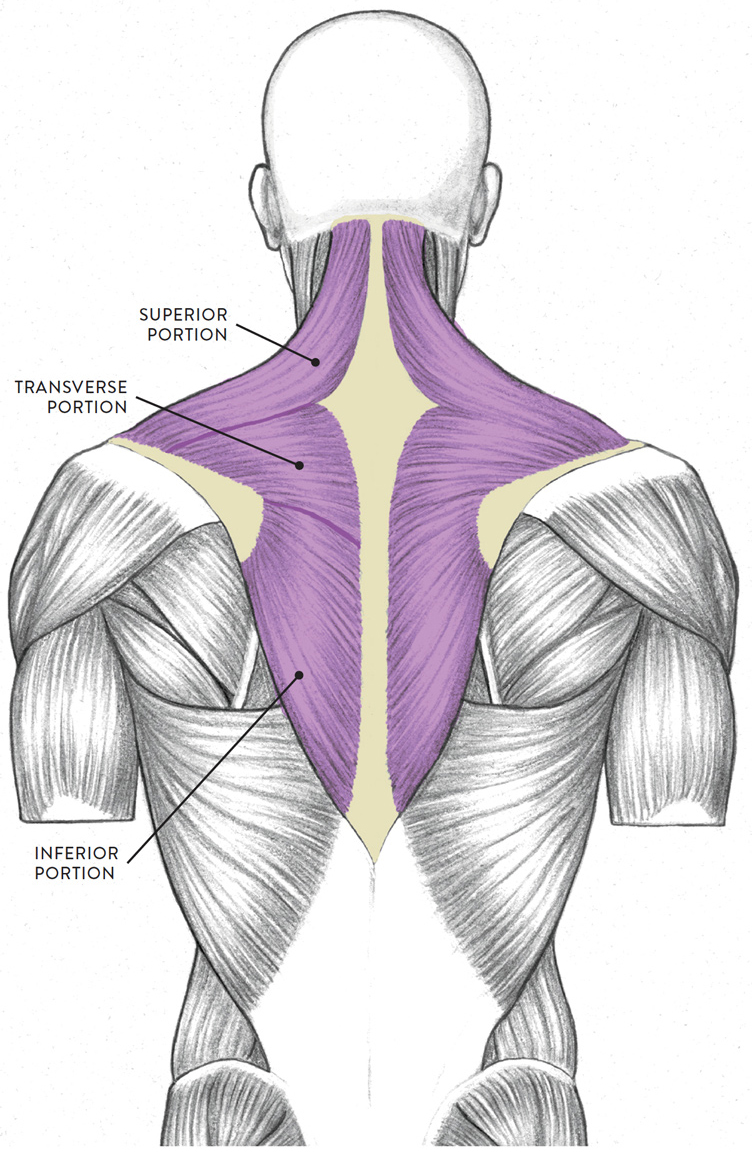

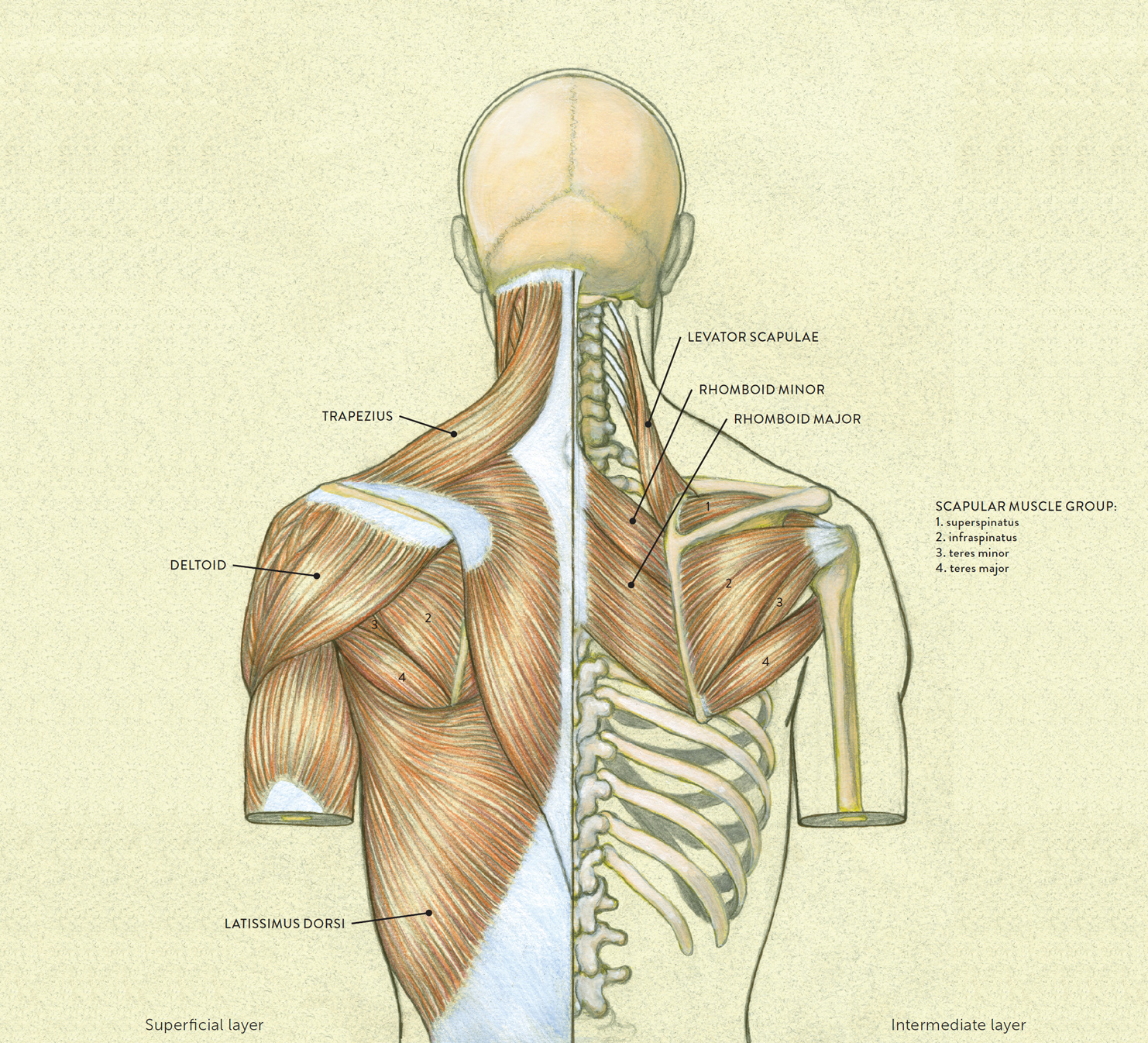

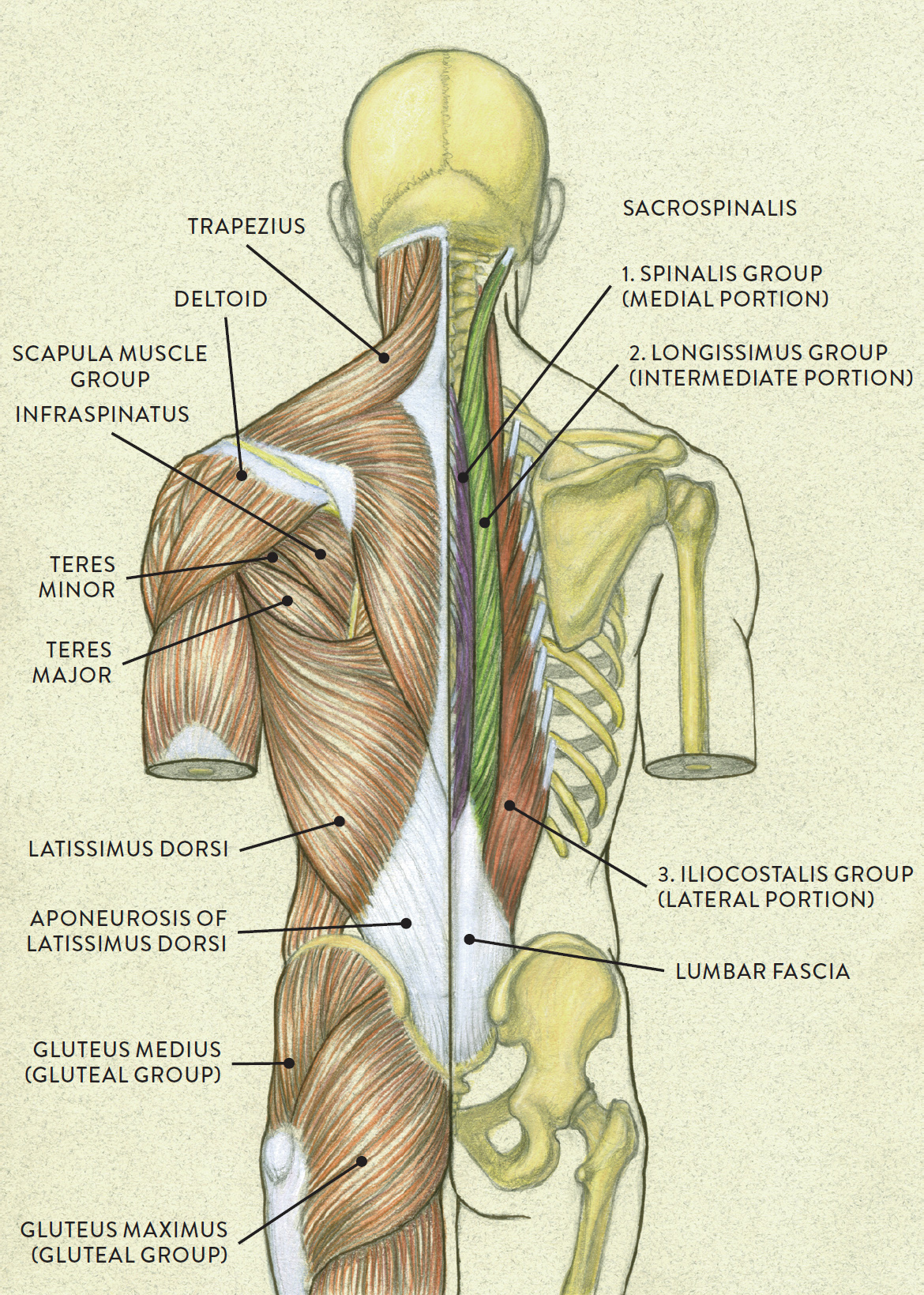

Muscles of the Back

The muscles of the back move the shoulder blade (scapula), upper arm (humerus), and back (vertebral column). They attach along the vertebral column and are divided into three muscle layers: The superficial layer contains the trapezius and the latissimus dorsi. The intermediate layer contains the rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, and levator scapulae. The deep layer contains the sacrospinalis. Muscles of the superficial and intermediate layers are shown in the drawing on this page; the muscles of the scapula and the deltoid muscle are included here but will be introduced separately, later in the chapter.

The Superficial Muscle Layer

The muscles of the superficial layer of the back move the shoulder blade (scapula) and upper arm (humerus). The two large main muscles of this layer are the trapezius and the latissimus dorsi.

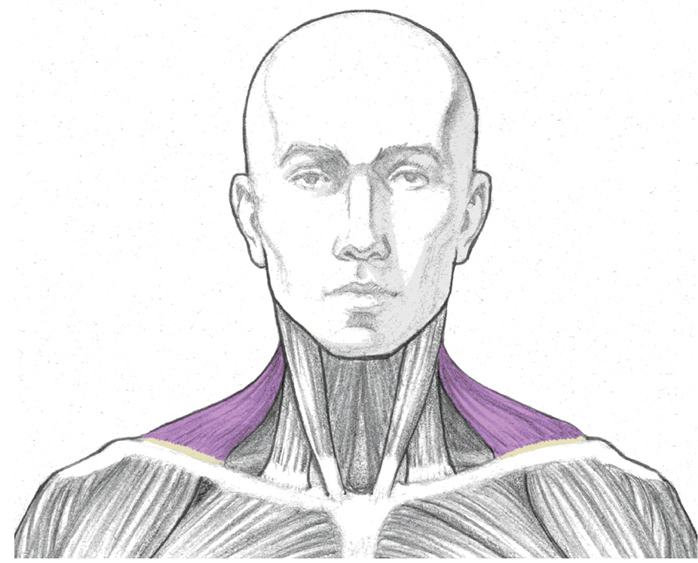

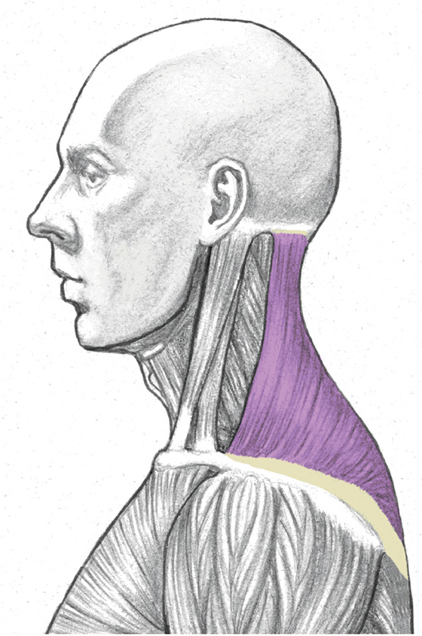

The trapezius (pron., traa-PEA-zee-us) is a trapezoid-shaped muscle positioned on the upper back. Its unique shape, shown in the following drawing helps create the shoulder forms, the back of the neck, and the muscle forms of the upper back. Its fibers divide into three portions: the superior (upper) portion, transverse (middle) portion, and inferior (lower) portion. The muscle originates at the base of the cranium (occipital protuberance), nuchal ligament, C7 (seventh vertebra), and all along the thoracic vertebrae. It inserts into the outer part of the clavicle, the spine of the scapula, and the acromion of the scapula.

TRAPEZIUS

Posterior view

Anterior view

Lateral view

Each portion of the trapezius helps move the scapula in a different way. These actions include lifting the scapula in an upward direction (elevation), tilting the scapula (upward rotation), and moving the scapula back (retraction/adduction). The upper portion of the muscle also helps bend the neck and head backward (extension of the neck).

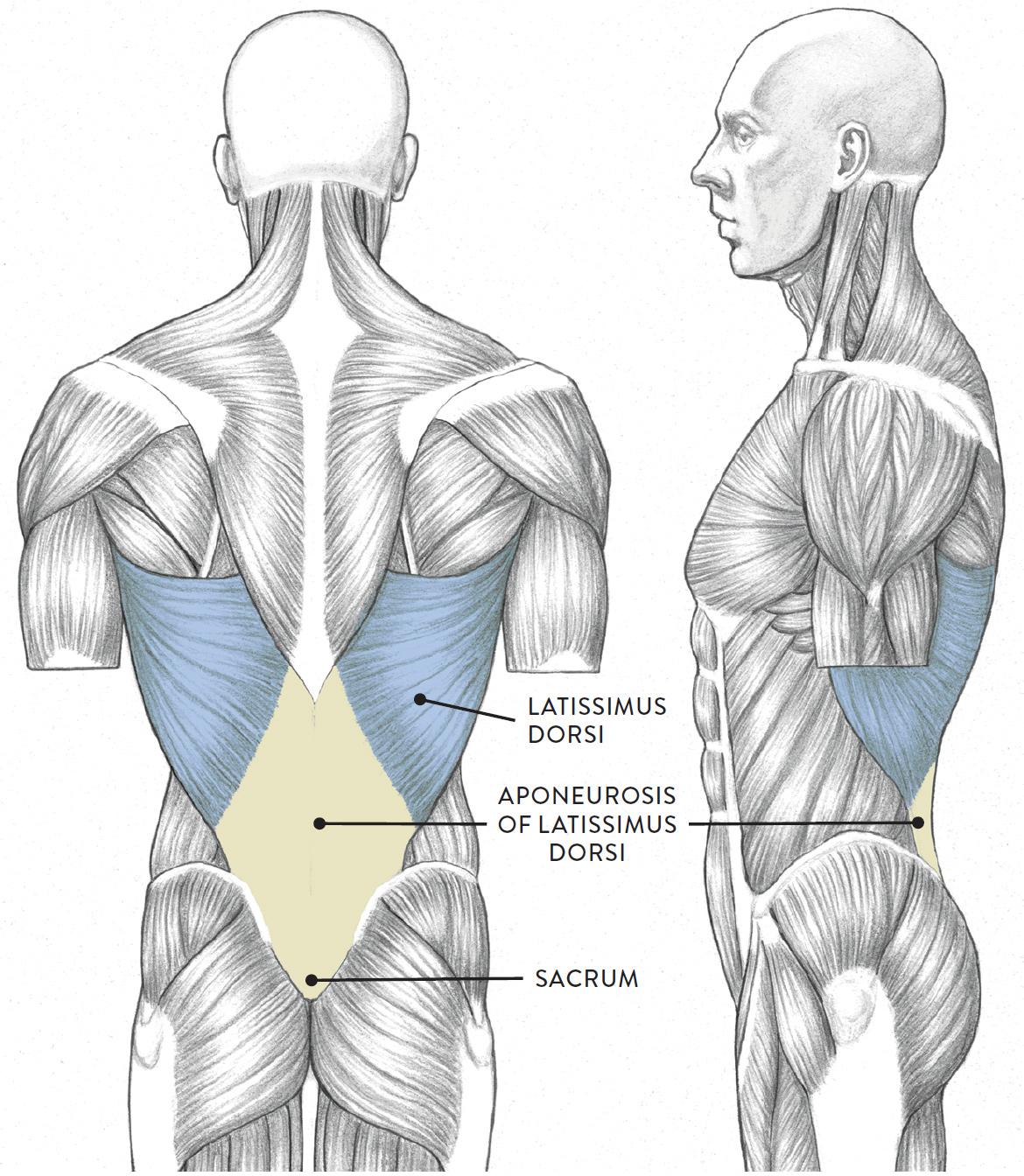

The latissimus dorsi (pron., lah-TISS-ih-mus DOR-see or lah-TISS-ih-muss DOR-sigh), shown in the following drawing, is a large triangular muscle that occupies most of the lower back region. On athletic figures (particularly body builders and swimmers) this muscle gives the back of the torso a V-shaped appearance. In a side view, when the arm is pulled forward, the outer edge of the muscle is usually seen as a thick curve obliquely crossing the torso and heading directly into the armpit of the upper arm, forming the posterior wall of the axillar region.

MUSCLES OF THE BACK

Superficial and intermediate muscle layers

LATISSIMUS DORSI

LEFT: Posterior view

RIGHT: Lateral view

The muscle begins on the thoracic vertebrae (T7–T12) and lumbar vertebrae (L1–L5), the ribs (ribs 10 through 12), the iliac crest of the pelvis, and the sacrum. It inserts into the humerus (upper arm bone). The latissimus dorsi assists in the actions of moving the humerus from a forward position back to the side of the torso (extension), moving the humerus from an overhead position and returning it to the side of the torso (adduction), and rotating the humerus in an inward direction (medial rotation).

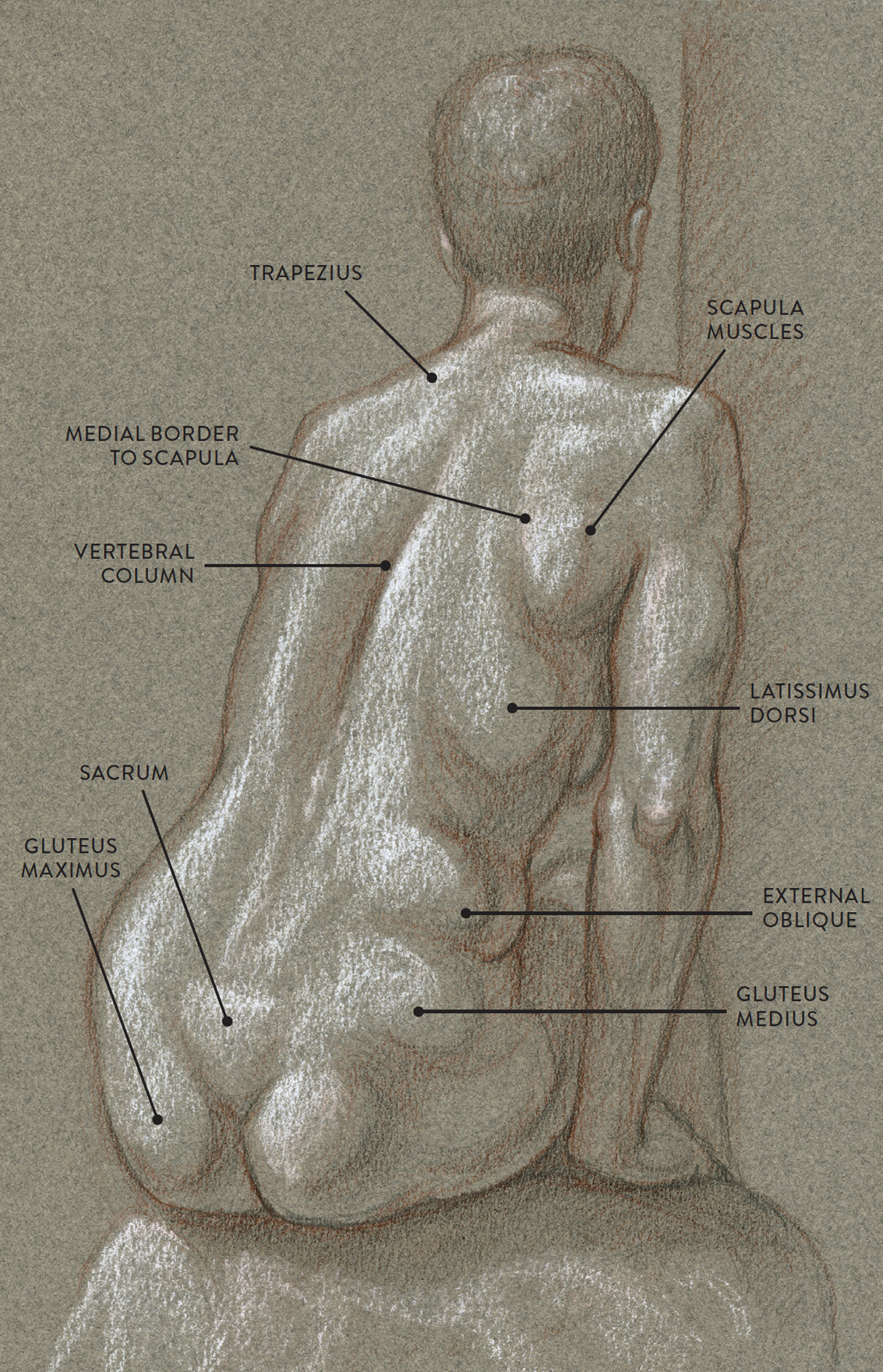

In the life study Female Figure in a Back View, Leaning Slightly, the back muscles appear very soft because of a padded layer of superficial fatty tissue. When approaching a study of a figure with a fair amount of fatty tissue, remain aware of the bony structure beneath. Try to find the locations of the vertebral column, sacrum, and scapula bones, because they help divide the back of the torso into workable components and serve as visual landmarks for the placement of muscle forms such as the trapezius, latissimus dorsi, and gluteal group. Once these are placed, the fatty tissue can be emphasized to create softer transitions on the surface form.

FEMALE FIGURE IN A BACK VIEW, LEANING SLIGHTLY

Graphite pencil, sanguine colored pencil, and white chalk on toned paper.

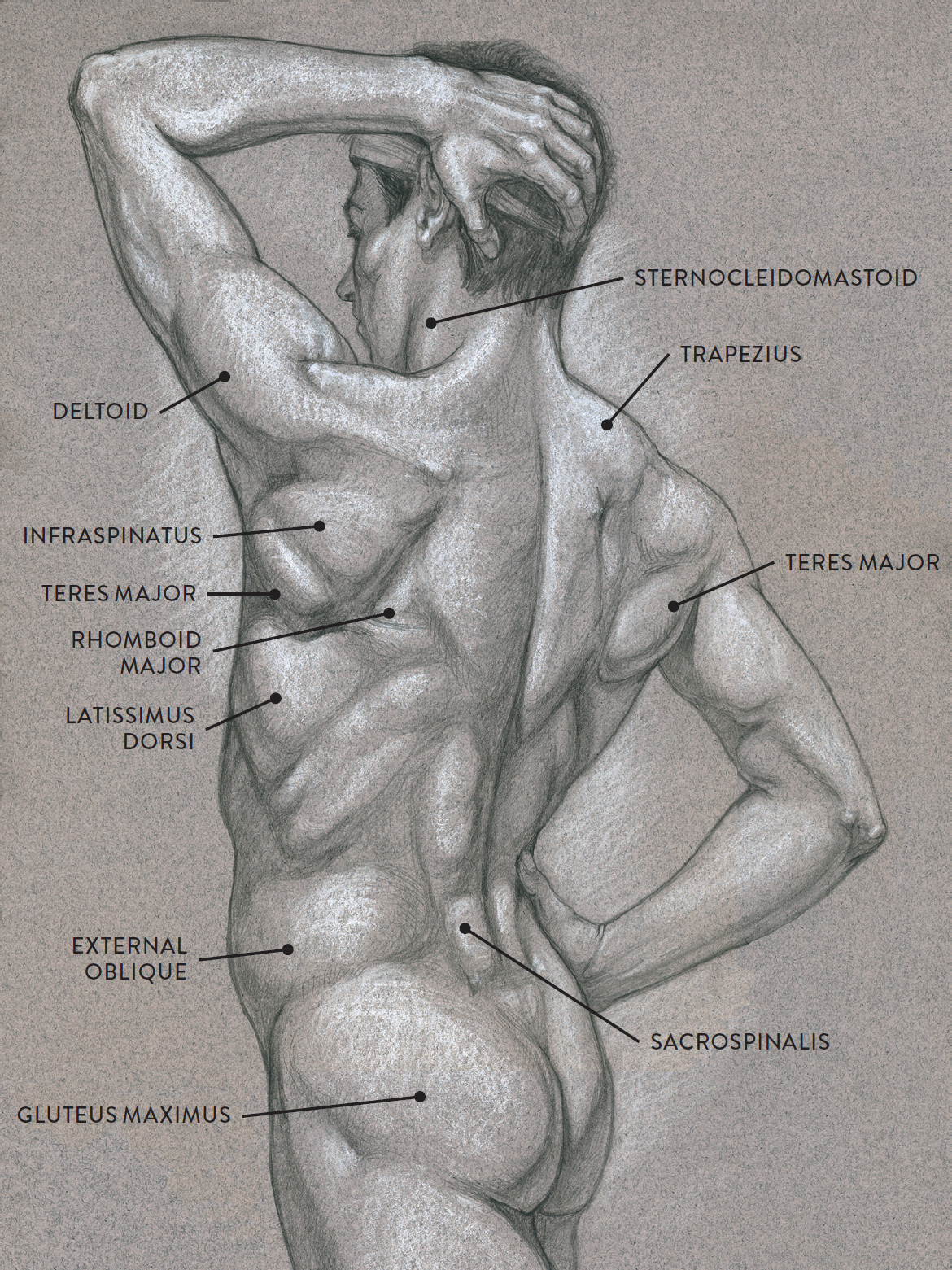

Now, compare the life study Male Figure in a Three-quarter Back View, with the study of the female figure. In this view of a male figure with one arm up and one arm on the hip, there is a tremendous number of clearly defined anatomical shapes, large and small. To avoid confusion when drawing such a muscular figure, first set up the general structures lightly—the shapes of the rib cage and pelvis, head and neck, and arm structures, along with the location of the vertebral column, sacrum, and the scapula bones. Then locate the large muscle shapes of the trapezius, latissimus dorsi, and the gluteal group. Medium-size forms such as the deltoid, the columnlike forms of the sacrospinalis, the flank pad of the external oblique, and the scapula muscles can be located next. Then go back to each larger muscle and continue to break down the various subforms you may see. Adding the tones and lights as you go helps keep the muscles connected and produces a sense of continuity.

MALE FIGURE IN A THREE-QUARTER BACK VIEW

Graphite pencil and white chalk on toned paper.

In poses such as this, you can see how the muscles change shape depending on the action of the arms and the placement of the rib cage and pelvis. The diagram accompanying the drawing further reveals the actions of the muscles in this pose.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The Intermediate Muscle Layer

The muscles of the intermediate muscle layer of the back are positioned beneath the trapezius and the latissimus dorsi. They include the rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, and levator scapulae and are responsible for helping to move the shoulder blade (scapula) and the upper arm (humerus).

The rhomboid minor and rhomboid major muscles attach between the vertebral column and the inner (medial) border of the scapula. Both are positioned beneath the superficial-layer trapezius muscle. The term rhomboid means “diamond shaped,” and together the rhomboids form a pair of parallelograms, one on either side of the vertebral column.

The rhomboid minor has a four-sided shape very similar to the geometric figure called a rhombus. The smaller of the two rhomboid muscles, it begins on the seventh vertebra of the neck (C7) and the first thoracic vertebra of the rib cage (T1) and inserts into the vertebral (or medial) border of the scapula.

The larger rhomboid major begins on the thoracic vertebrae (T2–T5) and inserts into the vertebral (or medial) border of the scapula. Only a small portion of the rhomboid major is ever visible on the surface, because most of the muscle is covered by the trapezius. It is occasionally evidenced by a small triangular bulge or depression between the outer border of the scapula, the outer lower border of the trapezius, and the upper border of the latissimus dorsi.

Both the rhomboid major and minor muscles participate in the actions of pulling the scapula toward the vertebral column (protraction/adduction), lifting the scapula in an upward direction (elevation), and tilting the scapula is a downward direction (downward rotation).

The levator scapulae (ley-VAY-tor SCAP-yoo-lee) has four individual muscle strips that merge into one muscle mass. It is positioned beneath the upper part of the trapezius muscle. The muscle begins on the first four cervical (neck) vertebrae and inserts into the outer upper edge of the scapula. The levator scapulae participates in moving the scapula in an upward direction (elevation) and tilting the scapula in a downward direction (downward rotation).

The Deep Muscle Layer

Within the deep muscle layer of the back is the sacrospinalis (pron., SAY-kro-spih-NAL-iss or SAY-kro-spy-NAY-liss), a large, columnlike muscle that divides into multiple segments. It is positioned beneath the rhomboid muscles of the intermediate layer and the trapezius and latissimus dorsi of the superficial layer. The drawing below shows the position of the sacrospinalis relative to the muscles of the superficial layer.

SUPERFICIAL AND DEEP MUSCLE LAYERS OF THE BACK

Left side: Superficial muscle layer

Right side: Deep muscle layer

The sacrospinalis, also known as the erector spinae, is an incredibly complex muscle. It is divided into three main groups on each side of the vertebral column: the iliocostalis group (outer/lateral portion), the longissimus group (intermediate/middle portion), and the spinalis group (medial/inner portion). Within each of these groups are further subdivisions. It is difficult to see all these subdivisions on the surface, though on muscular bodies the combination of the many components of this muscle creates two large, columnlike forms on either side of the vertebral column, beneath the latissimus dorsi and trapezius. On bodies with less muscle definition, the lower portion of this muscle appears as two slender cylindrical forms positioned side by side directly above the sacrum.

The muscle originates at the sacrum, all along the lumbar vertebrae (L1–L5), and at the last two thoracic vertebrae (T11–T12). It inserts into the angle of the ribs, along the cervical and thoracic vertebrae, and eventually into the mastoid process of the cranium. The sacrospinalis assists in the actions of moving the vertebral column from a forward-bending position back to an upright position (extension) and of bending the torso back (hyperextension). It also assists in bending the vertebral column and rib cage sideways (lateral flexion) and helps maintain the vertebral column in an upright posture when there is no physical movement (isometric contraction).

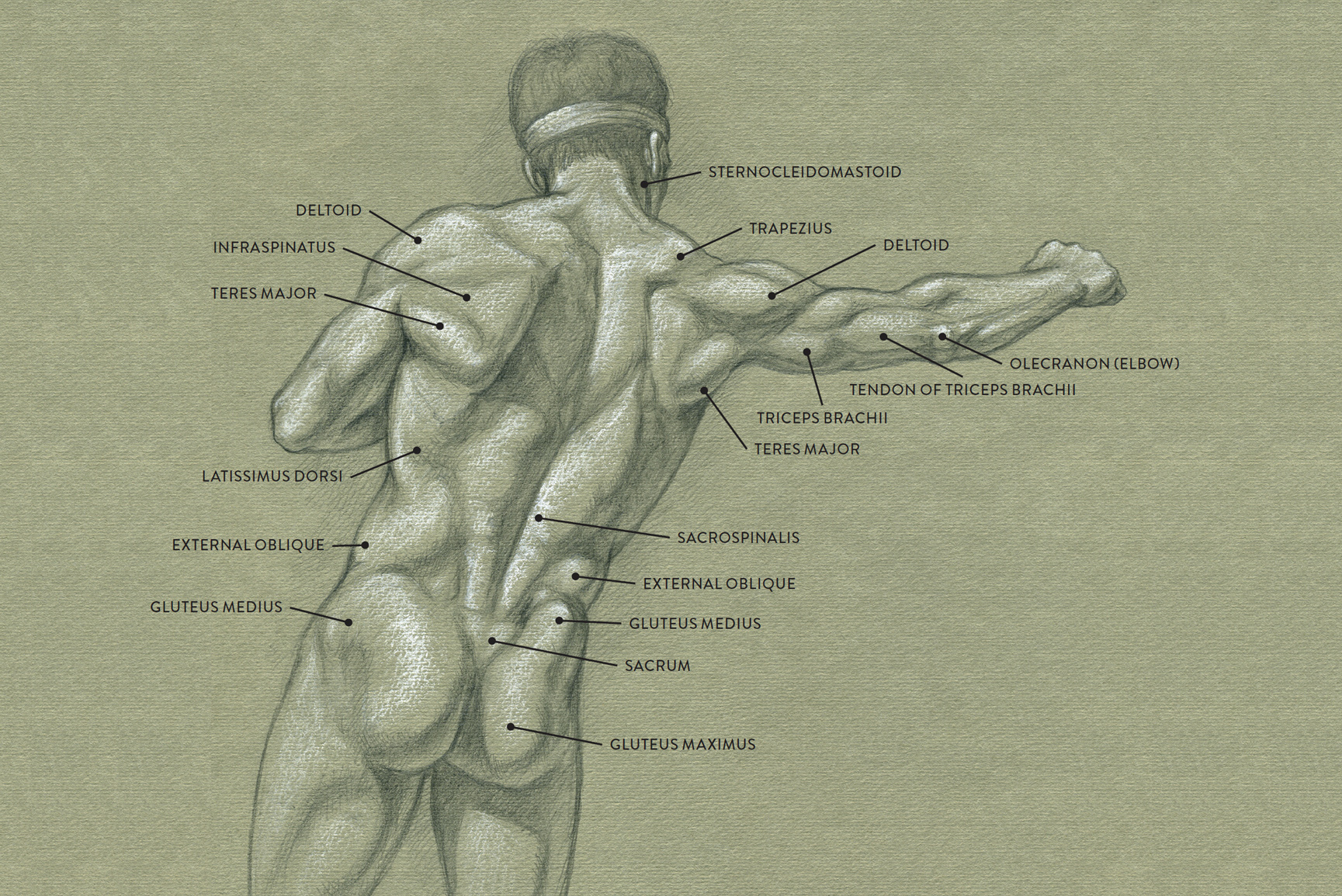

In the life study Male Figure in a Boxing Pose, several muscles of the figure’s back are very prominent because of their contracted state. The scapular muscle group, sacrospinalis, trapezius, and deltoid are especially noticeable, and the external oblique, latissimus dorsi, as well as the triceps brachii of the right arm are clearly visible, as well. The diagram accompanying the drawing further reveals the actions of the muscles in this pose.

MALE FIGURE IN A BOXING POSE

Graphite pencil and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

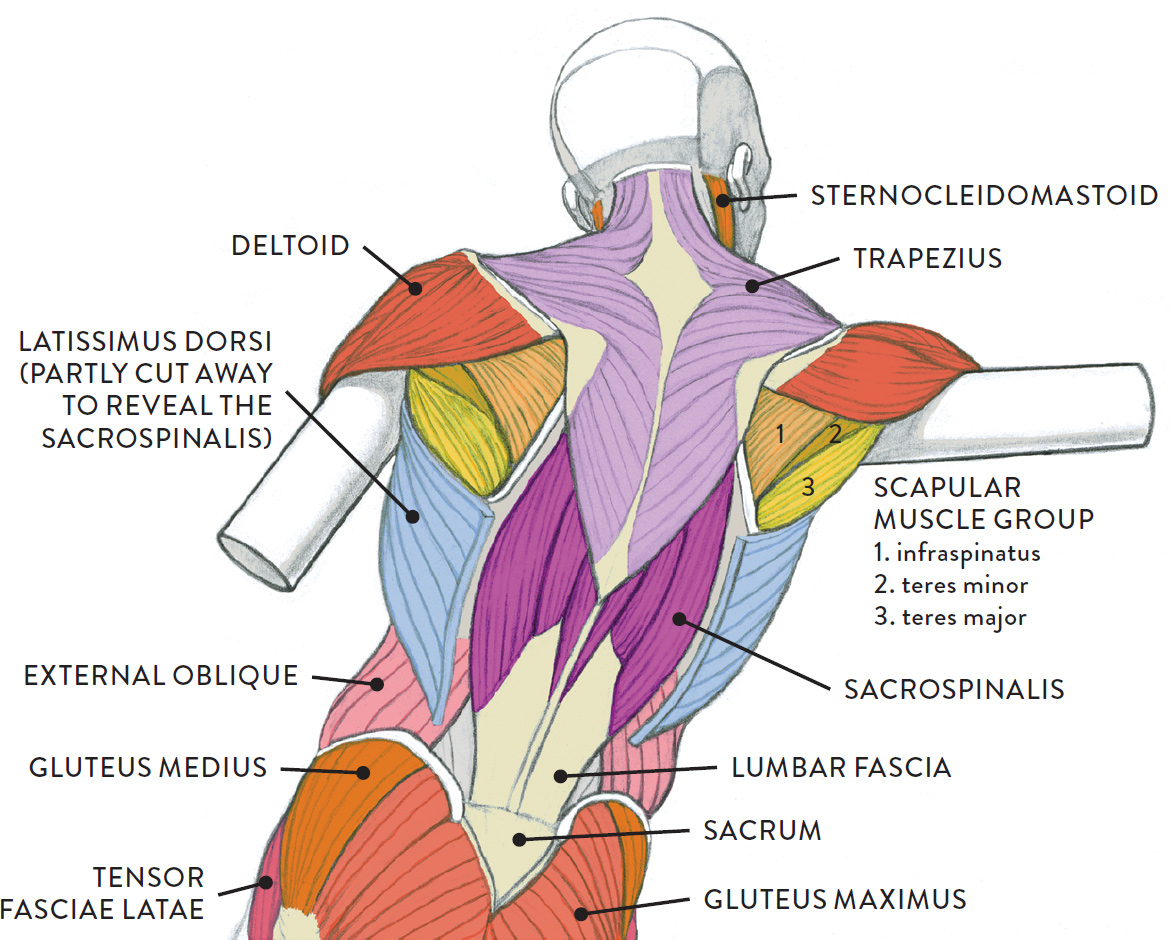

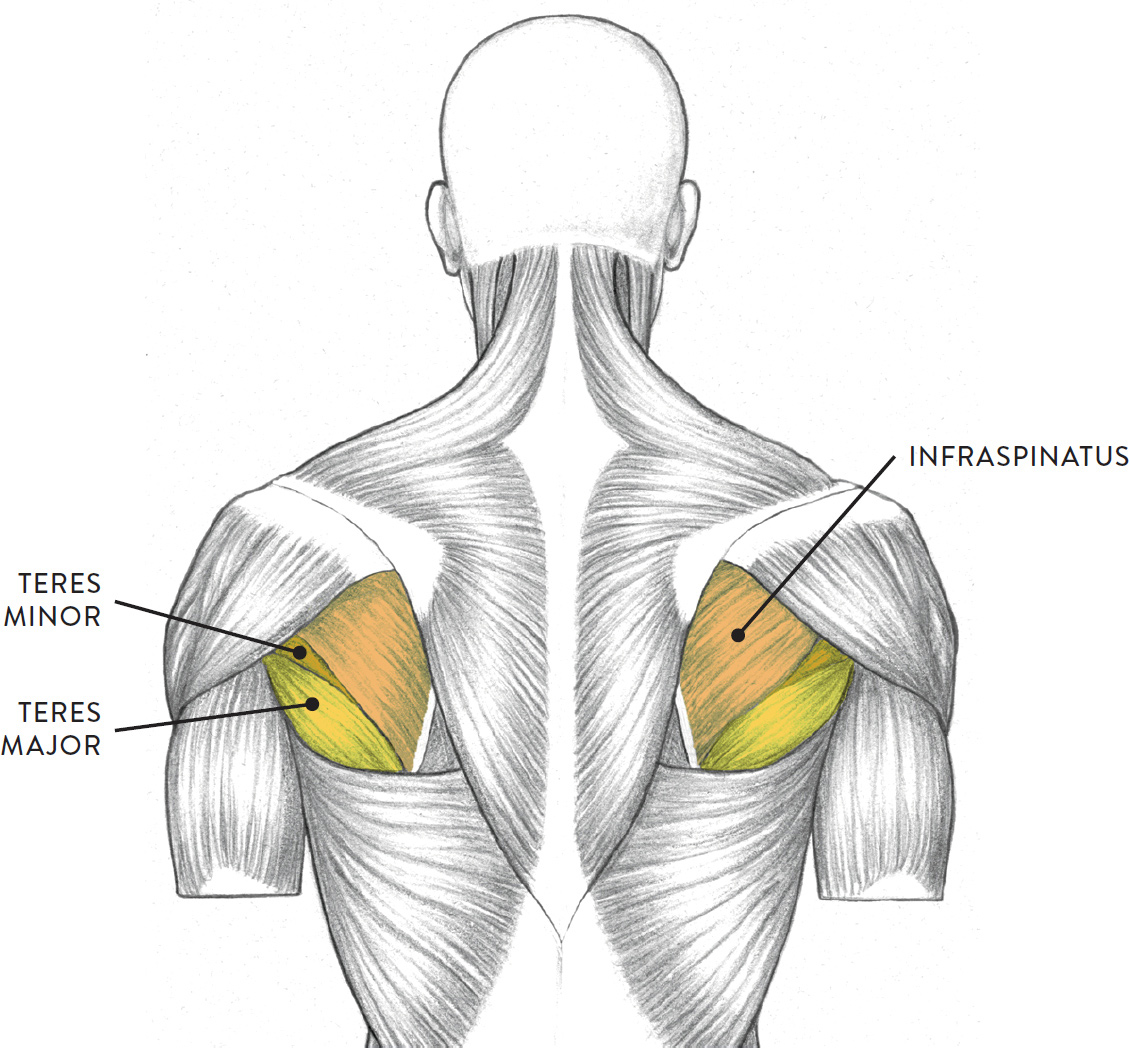

The Scapular Muscle Group

The muscles of the scapular group are the supraspinatus, subscapularis, infraspinatus, teres major, and teres minor. The supraspinatus is positioned on the upper part of the scapula and is completely covered by part of the trapezius muscle. The subscapularis is attached underneath the scapula and can never be seen on the surface. Therefore only the infraspinatus, teres major, and teres minor are shown in the following drawing.

SCAPULAR MUSCLE GROUP

Torso, posterior view

All these muscles originate on the scapula and insert into the humerus bone of the upper arm. The scapular muscle group does not move the scapula, even though the muscles attach directly on it. Their function is to move the humerus in various directions. Actions include moving the humerus away from the side of the torso (abduction), rotating the humerus in an outward direction (lateral rotation), rotating the humerus in an inward direction (medial rotation), returning the humerus from a outstretched side position to the side of the torso (adduction), and returning the humerus from a forward position back to the side of the torso (extension). Several movements of the upper arm, however, cannot be accomplished without the scapula also moving. This is made possible by another group of muscles, including the trapezius, rhomboid major and minor, levator scapulae, and pectoralis minor.

|

Scapular Muscle Group |

|

|

MUSCLE |

PRONUNCIATION |

|

supraspinatus |

SOO-prah-spih-NAH-tuss or |

|

infraspinatus |

IN-frah-spih-NAH-tuss or |

|

teres major |

teh-REEZ MAY-jur |

|

teres minor |

teh-REEZ MY-nor |

|

subscapularis |

SUB-scap-yoo-LAR-iss |

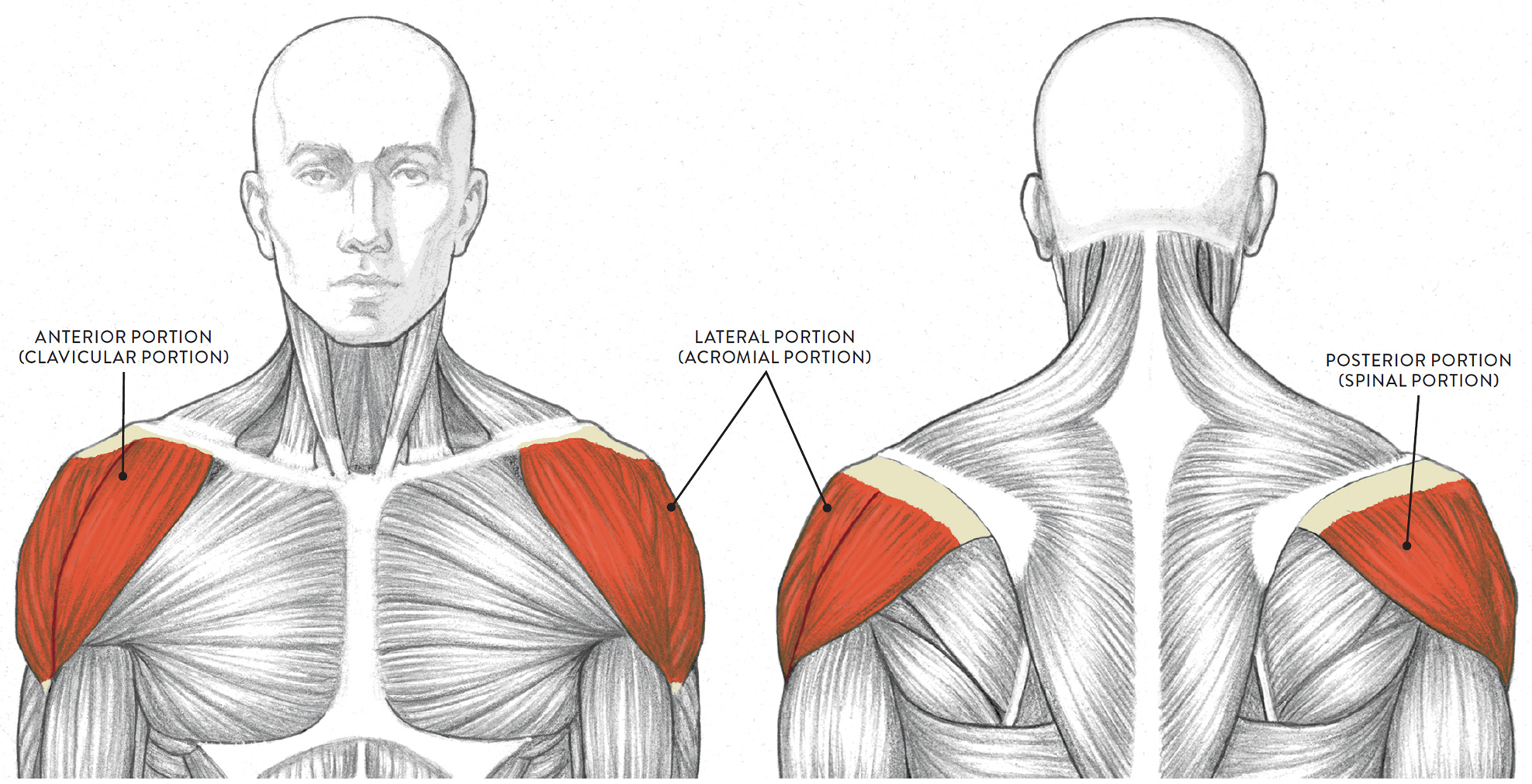

The Deltoid

The deltoid (pron., DELL-toyd) is the triangular muscle of the shoulder and upper arm. A transitional muscle linking the shoulder girdle of the torso and the upper arm, the deltoid can be said to belong both to the torso muscles and to the upper arm muscles.

The deltoid’s shape is similar to that of a sports shoulder pad. Surrounding the vulnerable shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) of the upper arm and scapula, the muscle appears as a triangular shape in front views and as an inverted teardrop or oval shape in side views of the arm.

The deltoid has three portions: the anterior portion (clavicular portion), which begins on the clavicle; the lateral portion (acromial portion), which begins on the acromion process of the scapula; and the posterior portion (spinal portion), which begins along the spine of the scapula. The muscle fibers converge to insert into a small attachment site approximately halfway down the outer part of the humerus. When the arms are lifted overhead, from a back view it is sometimes possible to see the separation of these portions around the clavicle and the acromion process of the scapula.

The deltoid moves the humerus to different positions depending on which portion is contracting and which other muscles are assisting. Actions include helping move the humerus in a forward direction (flexion), returning the humerus from a flexed position back to the side of the torso (extension), moving the humerus farther back (hyperextension), rotating the humerus in an inward direction (medial rotation), rotating the humerus in an outward direction (lateral rotation), and moving the humerus away from the side of the torso (abduction).

DELTOID

LEFT: Anterior view

RIGHT: Posterior view

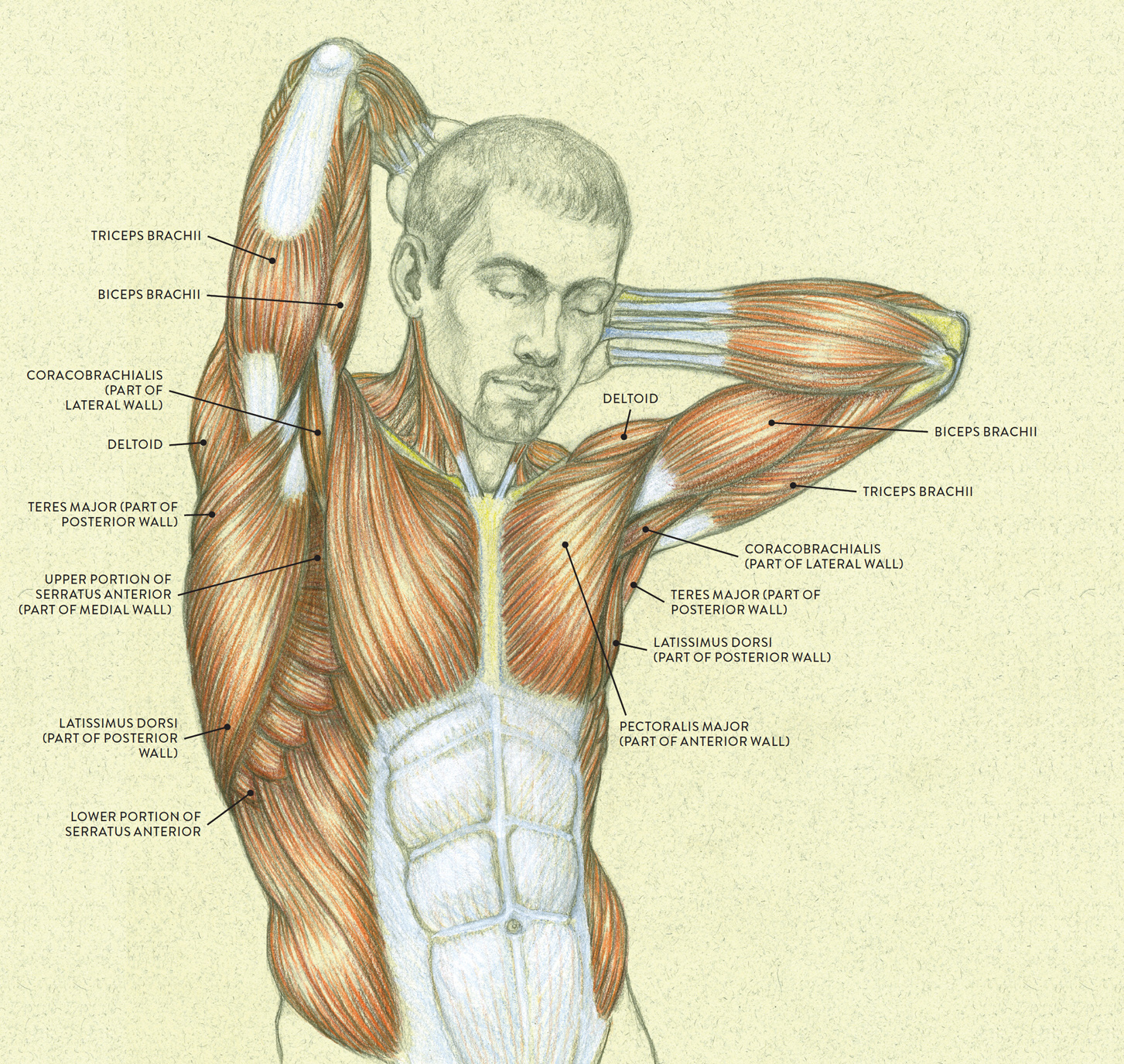

The Axilla

The axilla, or axillary region, is commonly referred to as the armpit, pit of the arm, or hollow of the arm. It is a junction of various muscles, softened with connective tissue and fatty tissue (fat pads). The skin pulls across the hollow created by the intersection of muscles as well as the contours of the muscles themselves. The axilla changes shape and size depending on the position of the arm in relation to the torso. When the arm is pulled away from the torso, the fatty tissue within the axilla temporarily recedes and a deep hollow occurs in this region (hence the name pit of the arm), but when the arm is raised overhead, the axilla appears as a soft mound.

There are several components of the axillar region, referred to as “walls” of the axilla: the anterior wall of the axilla, the posterior wall of the axilla, the medial wall of the axilla, and the lateral wall of the axilla. There is also the floor of the axilla. The anterior wall is created by the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles, and is seen on the surface quite clearly as a strong, muscular form moving from the rib cage into the upper arm. The upper portion of the coracobrachialis muscle is concealed by the anterior wall when the arm is at the side of the torso; when the arm is raised overhead, however, it appears as a small elongated form located next to the upper portion of the biceps; this area is the lateral wall. The posterior wall is formed by the teres major and latissimus dorsi muscles, along with the subscapularis muscle beneath. The medial wall consists of the upper four ribs and the upper four digitations of the serratus anterior muscle. The floor of the axilla consists of the axillar fascia and the skin stretching between the anterior and posterior walls. When the arms are pulled up or away from the torso, you can usually detect only the anterior and posterior walls, as well as the floor of the axilla. The coracobrachialis and a few of the fingerlike digitations of the serratus anterior located between the more obvious anterior and posterior walls may also be detected on the surface.

AXILLA/ARMPIT

Superficial muscle layer

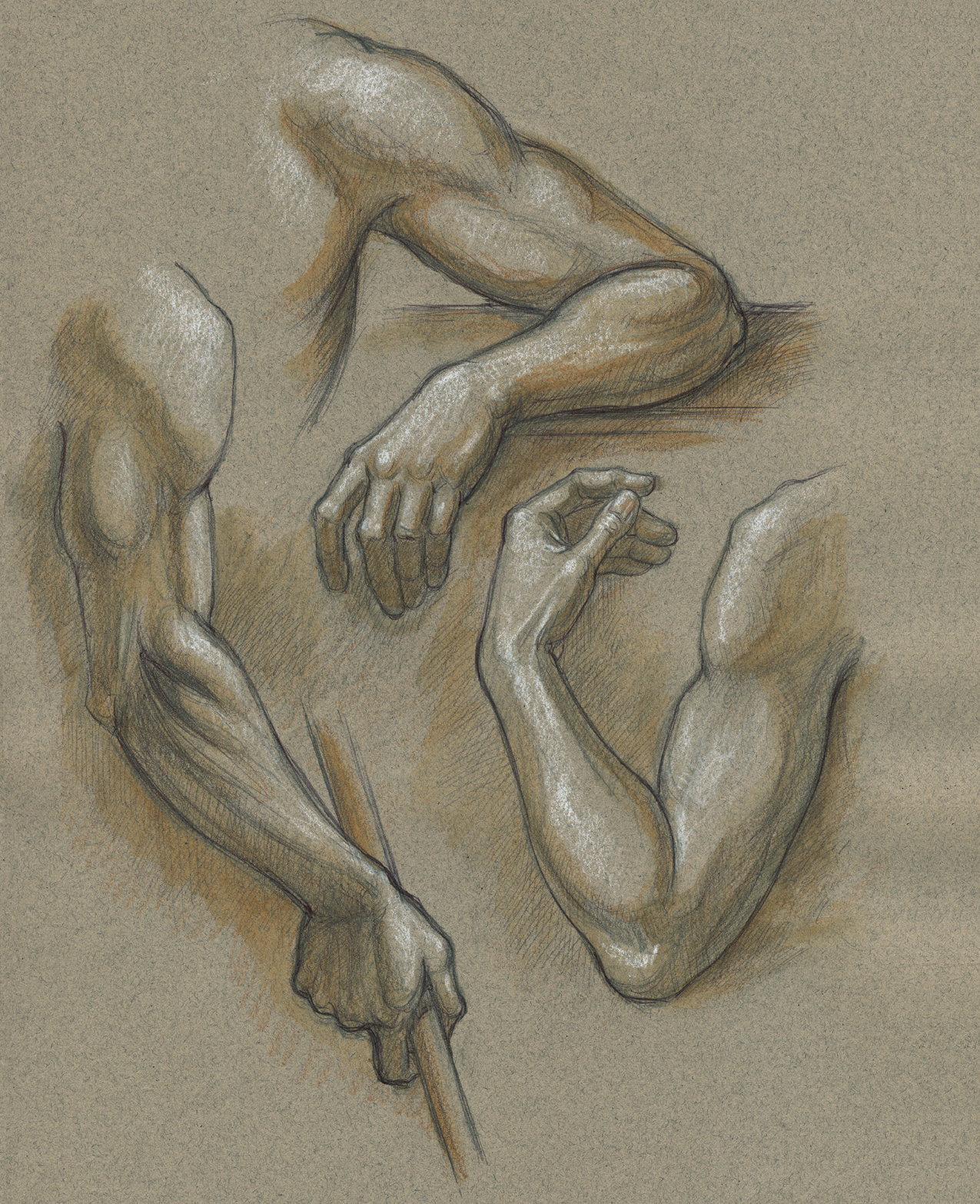

STUDY OF THREE ARMS

Graphite pencil, ballpoint pen, colored pencil, and white chalk on toned paper.