5 Steps to a 5: AP Chemistry 2024 - Moore J.T., Langley R.H. 2023

STEP 4 Review the Knowledge You Need to Score High

6 Stoichiometry

IN THIS CHAPTER

In this chapter, the following AP topics are covered:

1.1 Moles and Molar Mass

1.3 Elemental Composition of Pure Substances

3.7 Solutions and Mixtures

3.8 Representations of Solutions

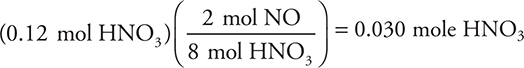

4.1 Introduction for Reactions

4.5 Stoichiometry

Summary: The previous chapter on chemical reactions discussed reactants and products in terms of individual atoms and molecules. But an industrial chemist is not interested in the number of molecules being produced; she or he is interested in kilograms or pounds or tons of products being formed per hour or day. How many kilograms of reactants will it take? How many kilograms of products will be formed? These are the questions of interest. A production chemist is interested primarily in the macroscopic world, not the microscopic one of atoms and molecules. Even a chemistry student working in the laboratory will not be weighing out individual atoms and molecules but measuring large numbers of them in grams. There must be a way to bridge the gap between the microscopic world of individual atoms and molecules, and the macroscopic world of grams and kilograms. There is—it is called the mole concept, and it is one of the central concepts in the world of chemistry.

Keywords and Equations

Avogadro’s number = 6.022 × 1023 mol—1

Molarity, M = moles solute per liter solution

n = moles

M = molar mass

m = mass

![]()

Moles and Molar Mass

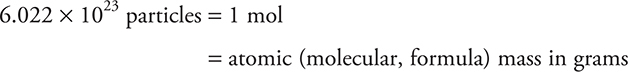

The mole (mol) is the amount of a substance that contains the same number of particles as atoms in exactly 12 grams of carbon-12. This number of particles (atoms or molecules or ions) per mole is called Avogadro’s number and is numerically equal to 6.022 × 1023 particles. (While this value is important to the understanding of chemistry, you will probably never see this value directly on the AP Chemistry Exam or any other standardized exam.) The mole is simply a term that represents a certain number of particles, like a dozen or a pair. That relates moles to the microscopic world, but what about the macroscopic world? The mole also represents a certain mass of a chemical substance. That mass is the substance’s atomic or molecular mass expressed in grams. In Chapter 5, the Basics chapter, we described the atomic mass of an element in terms of atomic mass units (amu). This was the mass associated with an individual atom. Then we described how one could calculate the mass of a compound by simply adding together the masses, in amu, of the individual elements in the compound. This is still the case, but at the macroscopic level the unit of grams is used to represent the quantity of a mole. Thus, the following relationships apply:

The mass in grams of one mole of a substance is the molar mass.

The relationship above gives a way of converting from grams to moles to particles, and vice versa. If you have any one of the three quantities, you can calculate the other two. This becomes extremely useful in working with chemical equations, as we will see later, because the coefficients in the balanced chemical equation are not only the number of individual atoms or molecules at the microscopic level but also the number of moles at the macroscopic level.

How many moles are present in 1.50 × 1029 helium atoms?

Answer:

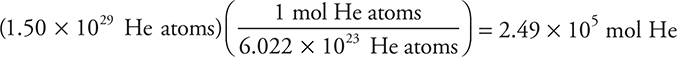

Percent Composition and Empirical Formulas

If the formula of a compound is known, it is a simple task to determine the percent composition of each element in the compound. For example, suppose you want to calculate the percentage of hydrogen and oxygen in water, H2O. First calculate the molecular mass of water:

![]()

Substituting the masses involved:

![]()

(intermediate calculation—don’t worry about significant figures yet)

Compare this to the percent composition of hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, which is 5.93% H and 94.07% O. (You may want to prove these numbers for yourself.)

As a good check, add the percentages together. They must sum to 100% or be very close to it.

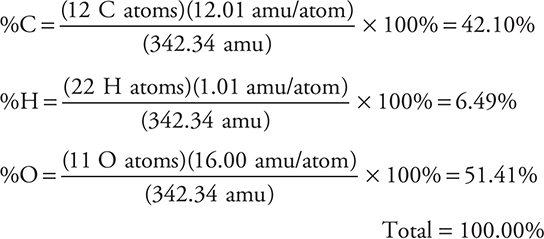

Determine the mass percent of each of the elements in cane sugar, C12H22O11. Formula mass (FM) = 342.34 amu

Answer:

The total is a check. It should be very close to 100%. (You may wish to prove to yourself that the significant figures are correct.)

In the problems above, the percentage data was calculated from the chemical formula, but the empirical formula can be determined if the percent compositions of the various elements are known. The empirical formula tells us what elements are present in the compound and the simplest whole-number ratio of elements. The data may be in terms of percentage, or mass, or even moles. But the procedure is still the same: convert each component to moles, divide each by the smallest number, and then use an appropriate multiplier if needed. The empirical formula mass can then be calculated. If the actual molecular mass is known, dividing the molecular mass by the empirical formula mass gives an integer (rounded if needed) that is used to multiply each of the subscripts in the empirical formula. This gives the molecular (actual) formula, which tells which elements are in the compound and the actual number of each. (Note: The percent composition of the empirical formula is identical to the percent composition of the molecular formula.)

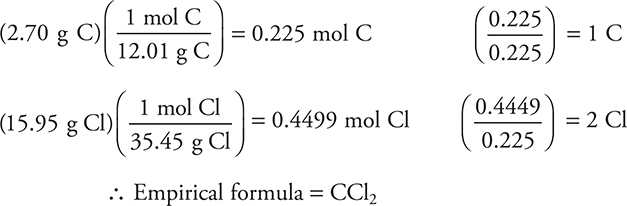

For example, a sample of an unstable gas was analyzed and found to contain 2.70 g of carbon and 15.95 g of chlorine. The molar mass of the gas was determined to be about 160 g/mol. What are the empirical and molecular formulas of this gas?

Answer:

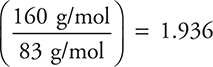

The molecular formula may be determined by dividing the actual molar mass of the compound by the empirical molar mass. In this case, the empirical molar mass is about 83 g/mol.

Thus  which, to one significant figure, is 2. Therefore, the molecular formula is twice the empirical formula—C2Cl4.

which, to one significant figure, is 2. Therefore, the molecular formula is twice the empirical formula—C2Cl4.

Be sure to use as many significant digits as possible in the molar masses. Failure to do so may give you erroneous ratio and empirical formulas. Note that the multiplier (2 in this example) must be an integer.

Introduction to Reactions

Matter undergoes many types of changes. Simplistically, these changes may be labelled as physical changes or chemical changes. In principle, all physical changes are reversible. For example, a simple change in temperature may cause water to undergo a physical change from solid ice to liquid water or vice versa. However, if you grind some salt into a fine powder, a physical change occurs, but it is one that is not easy to reverse. While these two examples are very different, these physical changes and others are characterized by no change in the composition of the substance. Water is H2O, no matter if it is ice, liquid water, or steam. Interconversion of the phases of water are known as phase changes. The properties may change during a physical change but not the composition.

Chemical changes involve a change in composition and usually cannot be reversed. For example, you cannot revers the chemical change that occurs when you burn a lump of charcoal. A chemical change may involve one substance such as in Priestley’s discovery by decomposing mercury(II) oxide to the mercury and oxygen by heating. Other chemical changes, often called chemical reactions, involve multiple substances. For example, the interactions of substance from food and from the air to keep you alive. In a chemical change, the conversion of substances to other substances (possibly accompanied by a phase change) may be accompanied by production of heat and/or light. Chemical changes may be described symbolically by a chemical equation. In Chapter 15, Equilibrium, you will see that some chemical changes are reversible.

The Law of Conservation of Mass is obeyed by both physical and chemical changes.

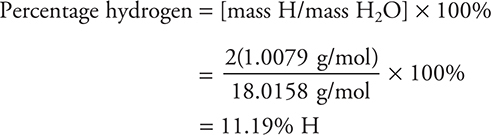

Reaction Stoichiometry

As we have discussed previously, the balanced chemical equation not only indicates which chemical species are the reactants and the products but also indicates the relative ratio of reactants and products. Consider the balanced equation of the initial step in the Ostwald process—the burning of ammonia:

![]()

This balanced equation can be read as: 4 ammonia molecules react with 5 oxygen molecules to produce 4 nitrogen oxide molecules and 6 water molecules. But as indicated previously, the coefficients can stand not only for the number of atoms or molecules (microscopic level), but they can also stand for the number of moles of reactants or products. The equation can also be read as: 4 moles ammonia react with 5 moles oxygen to produce 4 moles nitrogen oxide and 6 moles water. And if the number of moles is known, the number of grams or molecules can be calculated. This is stoichiometry, the calculation of the amount (mass, moles, particles) of one substance in a chemical reaction using another substance. The coefficients in a balanced chemical equation define the mathematical relationship between the reactants and products, and this allows the conversion from moles of one chemical species in the reaction to another.

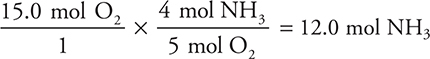

Consider the Ostwald process above. How many moles of ammonia are necessary to react completely with 15.0 mol of oxygen?

Before any stoichiometry calculation can be done, you must have a balanced chemical equation!

You are starting with moles of oxygen and want moles of ammonia, so we’ll convert from moles of oxygen to moles of ammonia by using the ratio of moles of oxygen to moles of ammonia as defined by the balanced chemical equation:

The ratio of 4 mol NH3 to 5 mol O2 is called the stoichiometric ratio and comes from the balanced chemical equation.

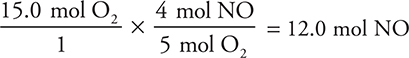

Suppose you also wanted to know how many moles of nitrogen oxide would form from the complete reaction of 15.0 mol of oxygen. Just change the stoichiometric ratio:

Notice that this new stoichiometric ratio also came from the balanced chemical equation.

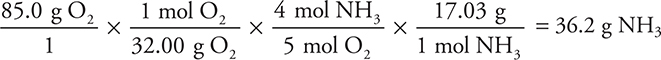

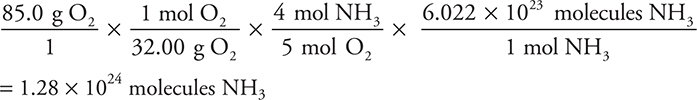

Suppose instead of moles you had grams and wanted an answer in grams. How many grams of ammonia would react with 85.0 g of oxygen gas?

In this problem we will convert from grams of oxygen to moles of oxygen to moles of ammonia using the correct stoichiometric ratio, and finally to grams of ammonia. And we will need the molar mass of O2 (32.00 g/mol) and ammonia (17.03 g/mol):

As an alternative, you could have calculated the number of ammonia molecules reacted if you had gone from moles of ammonia to molecules (using Avogadro’s number):

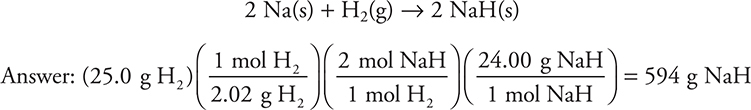

In the following reaction, 25.0 g of H2 and excess Na are combined to produce NaH. How many grams of NaH will form?

Limiting Reactants

In the examples above, one reactant was present in excess. One reactant was completely consumed, and some of the other reactant was left over. The reactant that is used up first is called the limiting reactant (LR). This reactant really determines the amount of product being formed. How is the limiting reactant determined? You can’t assume it is the reactant in the smallest amount, since the reaction stoichiometry must be considered. There are generally two ways to determine which reactant is the limiting reactant:

1. Each reactant, in turn, is assumed to be the limiting reactant, and the amount of product that would be formed is calculated. The reactant that yields the smallest amount of product is the limiting reactant. The advantage of this method is that you get to practice your calculation skills; the disadvantage is that you must do more calculations.

2. The moles of reactant per coefficient of that reactant in the balanced chemical equation is calculated. The reactant that has the smallest mole-to-coefficient ratio is the limiting reactant. This is the method that many people use.

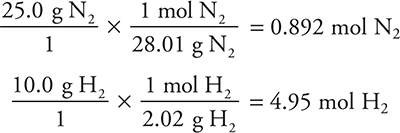

Let us consider the Haber reaction. Suppose that 25.0 g of nitrogen and 10.0 g of hydrogen react according to the following equation. Calculate the number of grams of ammonia that could be formed.

First, write the balanced chemical equation:

![]()

Next, convert the grams of each reactant to moles:

Divide each by the coefficient in the balanced chemical equation. The smaller is the limiting reactant:

For N2: ![]()

For H2: ![]()

Note that even though there were fewer grams of hydrogen, it was not the limiting reagent.

Finally, base the stoichiometry of the reaction on the limiting reactant:

Anytime the quantities of more than one reactant are given, it is probably an LR problem.

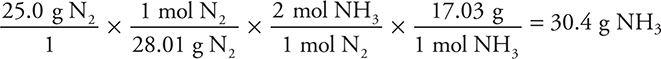

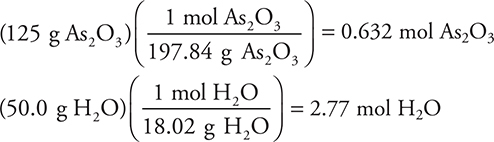

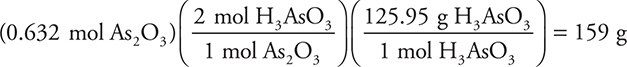

Let’s consider another case. To carry out the following reaction: As2O3(s) + 3H2O(l) → 2H3AsO3(aq), 125 g of As2O3 and 50.0 g of H3O were supplied. How many grams of H3AsO3 may be produced?

Answer:

1. Convert to moles:

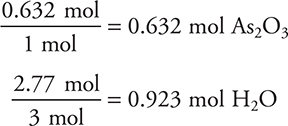

2. Find the limiting reactant:

The 1 mol and the 3 mol come from the balanced chemical equation. The 0.6320 is smaller, so this is the LR.

3. Finish using the number of moles of the LR:

Percent Yield

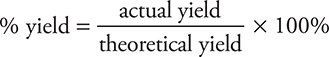

In the preceding problems, the amount of product calculated based on the limiting-reactant concept is the maximum amount of product that could be formed from the given quantity of reactants. This maximum amount of product formed is called the theoretical yield. However, rarely is the amount that is actually formed (the actual yield) the same as the theoretical yield. Normally it is less. There are many reasons for this, but the principal reason is that most reactions do not go to completion; they establish an equilibrium system (see Chapter 15, Equilibrium, for a discussion of chemical equilibrium). For whatever reason, not as much as expected is formed. The efficiency of the reaction can be judged by calculating the percent yield. The percent yield (% yield) is the actual yield divided by the theoretical yield, and the result is multiplied by 100% to generate percentage:

Consider the problem in which it was calculated that 40.3 g NH3 could be formed. Suppose that reaction was carried out, and only 34.7 g NH3 was formed. What is the percent yield?

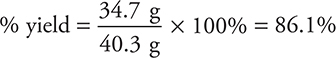

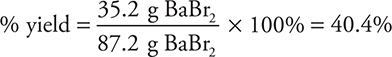

Let’s consider another percent yield problem in which a 45.0-g sample of barium oxide is heated with excess hydrogen bromide to produce water and 35.2 g of barium bromide. What is the percent yield of barium bromide?

![]()

Answer:

(45.0 g BaO)

The theoretical yield is 87.2 g.

Note: All the units except % must cancel. This includes canceling g BaBr2 with g BaBr2, not simply g.

Molarity and Solution Calculations

We discuss solutions further in Chapter 11 Solutions, but solution stoichiometry is so common on the AP Exam that we will discuss it here briefly also. Solutions are homogeneous mixtures composed of a solute (substance present in smaller amount) and a solvent (substance present in larger amount). If sodium chloride is dissolved in water, the NaCl is the solute and the water the solvent.

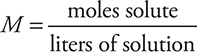

One important aspect of solutions is their concentration, the amount of solute dissolved in the solvent. There are numerous concentration units, some of which we will mention in Chapter 11. In this chapter, we will focus on molarity and how it relates to stoichiometry. Molarity (M) is defined as the moles of solute per liter of solution:

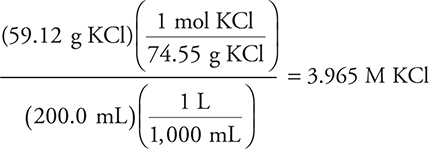

Let’s start with a simple example of calculating molarity. A solution of KCl contains 59.12 g of this compound in 200.0 mL of solution. Calculate the molarity of KCl.

Answer:

Knowing the volume of the solution and the molarity allows you to calculate the moles or grams of solute present.

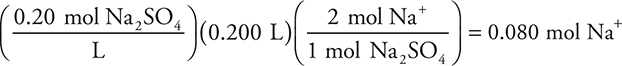

Next, let’s see how we can use molarity to calculate moles. How many moles of sodium ions are in 0.200 L of a 0.20 M sodium sulfate solution?

Answer:

Stoichiometry problems (including limiting-reactant problems) involving solutions can be worked in the same fashion as before, except that the volume and molarity of the solution must first be converted to moles.

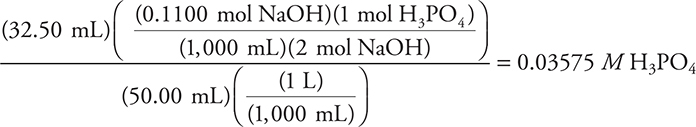

If 32.50 mL of a 0.1100 M NaOH solution is required to titrate 50.00 mL of a phosphoric acid solution, what is the concentration of the acid? The reaction is:

![]()

Answer:

Experiments

Stoichiometry experiments must involve moles. They nearly always use a balanced chemical equation. Measurements include initial and final masses, and initial and final volumes. Calculations may include the difference between the initial and final values (on the AP Exam you can never measure a difference). Using the formula mass and the mass in grams, moles may be calculated (not measured). Moles may also be calculated from the volume of a solution and its molarity.

Once the moles have been calculated (they are never measured), the experiment will be based on further calculations using these moles.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

1. Avogadro’s number is 6.022 × 1023 (not 10—23).

2. Be sure to know the difference between molecules and moles.

3. In empirical formula problems, be sure to get the lowest ratio of whole numbers.

4. In stoichiometry problems, be sure to use the balanced chemical equation.

5. The stoichiometric ratio comes from the balanced chemical equation.

6. When in doubt, convert to moles.

7. In limiting-reactant problems, don’t consider just the number of grams or even moles to determine the limiting reactant. Use the mol/coefficient ratio.

8. The limiting reactant is a reactant, a chemical species to the left of the reactant arrow.

9. Use the balanced chemical equation.

10. Percent yield is the actual yield of a substance divided by the theoretical yield of the same substance multiplied by 100%. (Normally the actual yield is given, and the theoretical yield is calculated.)

11. Molarity is moles of solute per liter of solution, not solvent.

12. Be careful when using Avogadro’s number—use it when you need or have the number of atoms, ions, or molecules.

![]() Review Questions

Review Questions

Use these questions to review the content of this chapter and practice for the AP Chemistry Exam. First are 20 multiple-choice questions similar to what you will encounter in Section I of the AP Chemistry Exam. Included are questions designed to help you review prior knowledge. Following those is a long free-response question like the ones in Section II of the exam. To make these questions an even more authentic practice for the actual exam, time yourself following the instructions provided.

Multiple-Choice Questions

Answer the following questions in 30 minutes. You may use the periodic table and the equation sheet at the back of this book.

1. How many milliliters of 0.100 M H2SO4 are required to neutralize 50.0 mL of 0.200 M KOH?

(A) 25.0 mL

(B) 30.0 mL

(C) 20.0 mL

(D) 50.0 mL

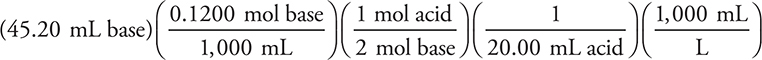

2. A sample of oxalic acid, H2C2O4, is titrated with standard sodium hydroxide, NaOH, solution. A total of 45.20 mL of 0.1200 M NaOH is required to completely neutralize 20.00 mL of the acid. What is the concentration of the acid?

(A) 0.2712 M

(B) 0.1200 M

(C) 0.1356 M

(D) 0.2400 M

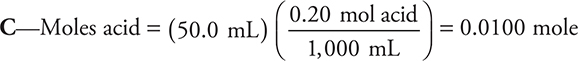

3. A solution is prepared by mixing 50.0 mL of 0.20 M arsenic acid, H3AsO4, and 50.0 mL of 0.20 M sodium hydroxide, NaOH. Which anion is present in the highest concentration?

(A) HAsO42—

(B) OH—

(C) H2AsO4—

(D) Na+

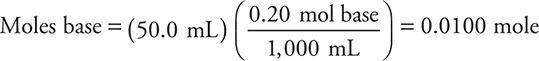

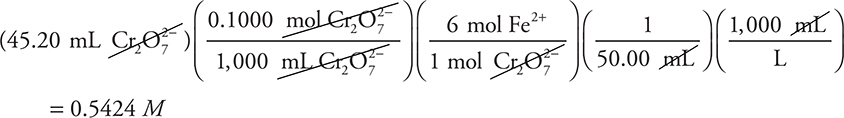

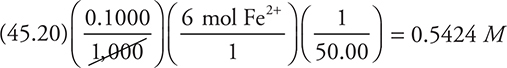

4. 14 H+(aq) + 6 Fe2+(aq) + Cr2O72—(aq) → 2 Cr3+(aq) + 6 Fe3+(aq) + 7 H2O(l)

This reaction is used in the titration of an iron solution. What is the concentration of the iron solution if it takes 45.20 mL of 0.1000 M Cr2O72— solution to titrate 50.00 mL of an acidified iron solution?

(A) 0.5424 M

(B) 0.1000 M

(C) 1.085 M

(D) 0.4520 M

5. Which of the following best represents the balanced net ionic equation for the reaction of silver carbonate with concentrated hydrochloric acid? Silver ions have a 1+ charge. In this reaction, all silver compounds are insoluble.

(A) 2 AgCO3(s) + 4 H+(aq) + Cl—(aq) → Ag2Cl(s) + CO2(g) + 2 H2O(l)

(B) Ag2CO3(s) + 2 H+(aq) + 2 Cl—(aq) → 2 AgCl(s) + CO2(g) + H2O(l)

(C) AgCO3(s) + 2 H+(aq) → Ag+(aq) + CO2(g) + H2O(l)

(D) Ag2CO3(s) + 4 Cl—(aq) → 2 AgCl2(s) + CO32—(aq)

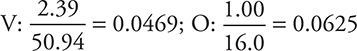

6. Vanadium forms several oxides. In which of the following oxides is the vanadium-to-oxygen mass ratio 2.39:1.00?

(A) VO

(B) V2O3

(C) V3O4

(D) VO2

7. A student takes a beaker containing 25.0 mL of 0.10 M magnesium nitrate, Mg(NO3)2, and adds, with stirring, 25.0 mL of a 0.10 M potassium hydroxide, KOH. A white precipitate of magnesium hydroxide immediately forms. Which of the following correctly indicates the relative concentrations of the other ions’ concentrations?

(A) [K+] > [Mg2+] > [NO3—]

(B) [Mg2+] > [NO3—] > [K+]

(C) [K+] > [NO3—] > [Mg2+]

(D) [NO3—] > [K+] > [Mg2+]

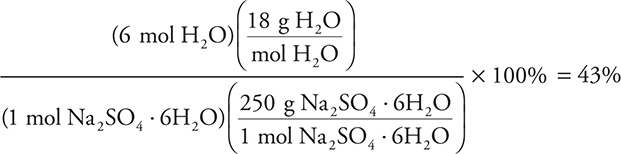

8. Sodium sulfate forms several hydrates. A sample of a hydrate is heated until all the water is removed. What is the formula of the original hydrate if it loses 43% of its mass when heated?

(A) Na2SO4 H2O

(B) Na2SO4 2H2O

(C) Na2SO4 6H2O

(D) Na2SO4 8H2O

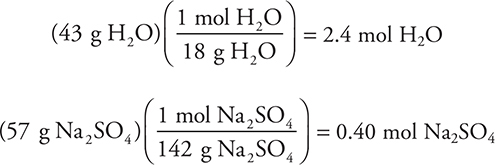

9. 3 Cu(s) + 8 HNO3(aq) → 3 Cu(NO3)2(aq) + 2 NO(g) + 4 H2O(l)

Copper metal reacts with nitric acid according to the above equation. A 0.30-mole sample of copper metal and 10.0 mL of 12 M nitric acid are mixed in a flask. How many moles of NO gas will form?

(A) 0.060 mole

(B) 0.030 mole

(C) 0.010 mole

(D) 0.20 mole

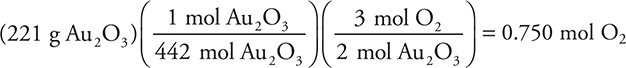

10. Gold(III) oxide, Au2O3, can be decomposed to gold metal, Au, plus oxygen gas, O2. How many moles of oxygen gas will form when 221 g of solid gold(III) oxide is decomposed? The formula mass of gold(III) oxide is 442 g/mole.

(A) 0.250 mole

(B) 0.500 mole

(C) 0.750 mole

(D) 1.00 mole

11. Which of the following is the correct net ionic equation for the reaction of nitrous acid, HNO2, with sodium hydroxide, NaOH?

(A) HNO2(aq) + OH—(aq) → NO2—(aq) + H2O(l)

(B) HNO2(aq) + Na+(aq) → NaNO2(s) + H+(aq)

(C) HNO2(aq) + NaOH(aq) → NaNO2(s) + H2O(l)

(D) H+(aq) + OH—(aq) → H2O(l)

12. 2 KMnO4(aq) + 5 H2C2O4(aq) + 3 H2SO4(aq) → K2SO4(aq) + 2 MnSO4(aq) + 10 CO2(g) + 8 H2O(l)

How many moles of MnSO4 are produced when 1.0 mole of KMnO4, 5.0 moles of H2C2O4, and 3.0 moles of H2SO4 are mixed?

(A) 4.0 moles

(B) 5.0 moles

(C) 2.0 moles

(D) 1.00 mole

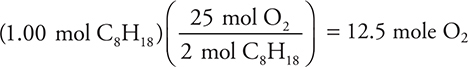

13. When the following equation is balanced, it is found that 1.00 mole of C8H18 reacts with how many moles of O2?

_____ C8H18(g) + _____ O2(g) → _____ CO2(g) + _____ H2O(g)

(A) 12.5 moles

(B) 10.0 moles

(C) 25.0 moles

(D) 37.5 moles

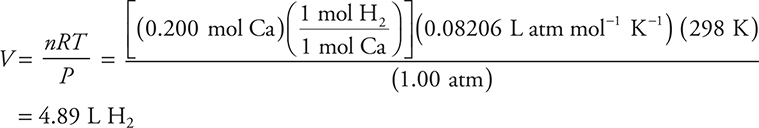

14. Ca(s) + 2 H2O(l) → Ca(OH)2(aq) + H2(g)

Calcium reacts with water according to the above reaction. What volume of hydrogen gas, at 25°C and 1.00 atm, is produced from 0.200 mole of calcium?

(A) 4.48 L

(B) 4.89 L

(C) 3.36 L

(D) 0.410 L

15. 2 CrO42—(aq) + 3 SnO22—(aq) + H2O(l) → 2 CrO2—(aq) + 3 SnO32—(aq) + 2 OH—(aq)

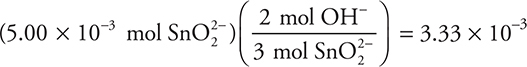

How many moles of OH— form when 50.0 mL of 0.100 M CrO42— is added to a flask containing 50.0 mL of 0.100 M SnO22—?

(A) 0.100 mole

(B) 6.66 × 10—3 mole

(C) 3.33 × 10—3 mole

(D) 5.00 × 10—3 mole

16. A solution containing 0.20 mole of KBr and 0.20 mole of MgBr2 in 2.0 L of water is provided. How many moles of Pb(NO3)2 must be added to precipitate all the bromide as insoluble PbBr2?

(A) 0.10 mole

(B) 0.50 mole

(C) 0.60 mole

(D) 0.30 mole

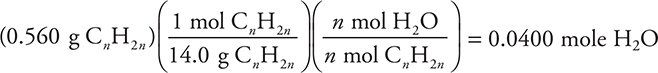

17. Cycloalkanes are hydrocarbons with the general formula CnH2n, where n ≥ 3. If a 0.560-g sample of any alkene is combusted in excess oxygen, how many moles of water will form?

(A) 0.0400 mole

(B) 0.600 mole

(C) 0.0200 mole

(D) 0.400 mole

18. For which of the following substances is the formula mass the same for both the empirical and molecular formulas?

(A) H2C2O4

(B) C6H12O6

(C) CO2

(D) H2O2

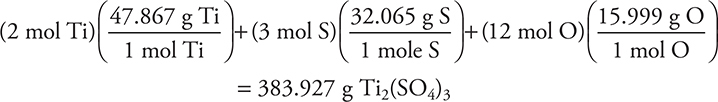

19. How many grams of Ti2(SO4)3 are necessary to make 500.0 mL of a solution that is 0.1000 M Ti3+?

(A) 38.393 g

(B) 9.598 g

(C) 17.42 g

(D) 19.20 g

20. A chemist performs the following reaction: Mg(s) + I2(s) → MgI2(s)

She begins with 2.30 grams of Mg and 26.0 grams of I2 and produces 2.63 g of MgI2.

Which of the following will lead to more MgI2 being produced?

(A) Adding I2(s)

(B) Increasing the pressure

(C) Adding Mg(s)

(D) Decreasing the temperature

![]() Answers and Explanations

Answers and Explanations

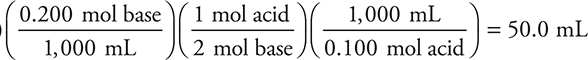

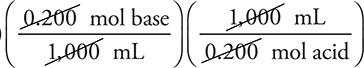

It is possible to simplify the calculations by replacing the definition of molarity  with the equivalent expression

with the equivalent expression

1. D—The reaction is H2SO4(aq) + 2 KOH(aq) → K2SO4(aq) + 2 H2O(l). The calculation is:

(50.0 mL base)

This calculation simplifies to (50.0 mL base)

Make sure you understand why the simplified calculation works. If you did not balance the equation, you probably used the wrong mole ratio and obtained 100.0 mL.

2. C—The reaction is H2C2O4(aq) + 2 NaOH(aq) → Na2C2O4(aq) + 2 H2O(l).

As in question 1, if you do not balance the equation, you get the wrong mole—mole ratio. The calculation is:

= 0.1356 M acid

As always, round the values to get an estimate and pick the closest answer.

3.

Answer B cannot be correct because the base is the limiting reagent.

There is enough base to react completely with only one of the ionizable hydrogen ions from the acid. This leaves H2AsO4—. The net ionic equation is:

![]()

Answer D cannot be correct because it is a cation.

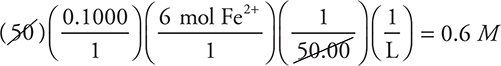

4. A— The balanced chemical equation is given, and the calculation is:

This is a perfect example of where simplification is important. Change the above calculation to:

This becomes:

Next, round and simplify to:

It is unnecessary to write everything shown here; you need only write/do the final calculation.

Since the 45.20 was rounded up, the answer is slightly high; therefore, pick the closest answer that is slightly lower.

5. B—The question states that in this reaction, all silver compounds are insoluble, which means that Ag+ is not a possible product since it must come from a compound. Silver carbonate is insoluble, and its formula should be written as Ag2CO3. Hydrochloric acid is a strong acid, so it should be written as separate H+ and Cl— ions. Silver chloride, AgCl, is insoluble, and carbonic acid, H2CO3, quickly decomposes to CO2 and H2O. Answers C and D are not balanced.

6. C—Begin by dividing each value in the given ratio by the atomic mass of the element:

Divide by the smaller value (0.0469):

It is necessary to have a whole-number ratio. The value 1.33 is too far from a whole number to round; therefore, it is necessary to multiply by the smallest value leading to a whole number. Multiplying both by 3 gives 3 V and 4 O, which corresponds to answer C.

7. D—The doubling of the volume will result in halving the concentrations (Mg2+ = 0.050 M, NO3— = 0.10 M, K+ = 0.050 M, and OH— = 0.050 M ). The reaction is:

![]()

After the reaction, some of the magnesium remains (the remainder precipitated, leaving < 0.050 M ), the potassium does not change (soluble, so still 0.050 M ), and there are two nitrate ions (soluble, so still 0.10 M ) per magnesium nitrate.

8. C—The calculation is a percent composition calculation. This technically should be done for all four answers; however, you probably will not need more than two. For answer C, the calculation is:

The numerator gives the mass of the water molecules present, and the denominator is from the molar mass of the formula. The percentages for the other compounds are 11% (A), 20% (B), and 50% (D). As in other calculations, rounding will simplify the work. As an alternative, it is possible to solve this problem using an empirical formula calculation based on 43% H2O and (100 — 43)% = 57% Na2SO4. In this case, assume 100 g of sample (which makes the percentages equal to the grams present):

Dividing each of the moles by the smaller value (0.40 mol) gives 1 Na2SO4 for 6 H2O.

9. B—Calculate the moles of acid to compare to the 0.30 mole of Cu:

The acid is the limiting reactant, because 0.30 mole of copper requires 0.80 mole of acid. Use the limiting reactant to calculate the moles of NO formed:

10. C—The balanced chemical equation is 2 Au2O3(s) → 4 Au(s) + 3 O2(g).

Note the 2:1 relationship between the formula mass and the mass of reactant.

11. A—The molecular equation is HNO2(aq) + NaOH(aq) → NaNO2(aq) + H2O(l).

Nitrous acid is a weak acid; as such, it should remain as HNO2. Sodium hydroxide is a strong base, so it will separate into Na+ and OH— ions. Any sodium compound that might form is soluble and will yield Na+ ions. The sodium ions are spectator ions and are left out of the net ionic equation. Answer D only works for a strong acid and a strong base.

12. D—The KMnO4 is the limiting reagent (2.0 moles of KMnO4 are required to react with the given amounts of the other reactants). Each mole of KMnO4 will produce a mole of MnSO4.

13. A—The balanced equation is ![]() The calculation is:

The calculation is:

14. B—Use the ideal gas equation (PV = nRT) and rearrange to isolate the volume:

Answer D is the result of not converting from °C to K. Answer A is the result of using 22.4 L mol—1 when you are not at STP.

15. C—There are (50 mL)  and an equal number of moles of

and an equal number of moles of ![]() Thus,

Thus, ![]() is the limiting reactant (larger coefficient in the balanced reaction).

is the limiting reactant (larger coefficient in the balanced reaction).

16. D—The volume of water is irrelevant. 0.20 mole of KBr will require 0.10 mole of Pb(NO3)2, and 0.20 mole of MgBr2 will require 0.20 mole of Pb(NO3)2. Total the two yields to get the final answer.

17. A—One mole of a cycloalkane, CnH2n, will form n moles of water.

![]()

It is possible to determine the value of n by dividing the mass of the cycloalkane by the empirical formula mass (CH2 = 14 g/mole). This gives:

18. C—For the formula mass of the empirical formula to be the same as that of the molecular formula, the two formulas must be the same. All the molecular formulas except CO2 can be simplified to give an empirical formula that is different from the molecular formula.

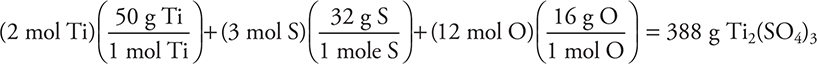

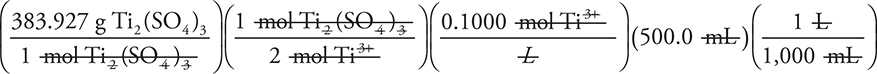

19. B—The molar mass of Ti2(SO4)3 is

Rounding simplifies everything:

(Since the rounded answer is slightly higher, using it will produce an answer that is too high.)

To determine the necessary grams:

= 9.598175 g Ti2(SO4)3 (correct unit; all other units cancelled as shown)

(Using the rounded molar mass gives 9.7 g.)

The 17.42 g answer comes if you accidently read Ti as Tl in the formula (we have seen many variations of this on actual exams).

The 19.20 g answer comes if you skip the 2 in the formula (second step in the calculation). We see students doing this on the exam when they do not bother to write out the units while working problems. A similar answer results if you forget to include the volume of the solution.

The 38.393 answer comes from an incorrect volume conversion (dividing 1,000 by 500.0, another error we have seen on exams we have graded, mainly because there were no units written).

20. C—The quantities of more than one reactant are given; therefore it is necessary to determine which reactant is limiting. To determine the limiting reactant, it is necessary to convert the mass of the reactants to moles:

Instead of doing the calculations shown, rounding might help. Noticing that the masses given are slightly below 0.1 mole for the Mg and slightly above 0.1 mole for I2, is really all that is necessary. Since the reaction has 1:1 stoichiometry, the reactant with the fewer moles (Mg) is limiting.

Adding more limiting reactant (Mg) will increase the yield.

Adding more excess reactant (I2) will not increase the yield.

Increasing the pressure is irrelevant since no gases are involved.

Decreasing the temperature may result in it taking longer before the reaction goes to completion, but it will not change the yield.

![]() Free-Response Question

Free-Response Question

You have 15 minutes to answer the following question. You may use a calculator and the tables in the back of the book.

Question

The analysis of a sample of a monoprotic acid found that the sample contained 40.0% C and 6.71% H. The remainder of the sample was oxygen.

(a) Determine the empirical formula of the acid. Show all work.

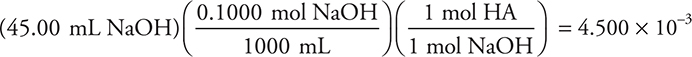

(b) A 0.2720-g sample of the acid, HA, was titrated with standard sodium hydroxide, NaOH, solution. Determine the molecular weight of the acid if the sample required 45.00 mL of 0.1000 M NaOH for the titration. Show all work.

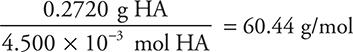

(c) A second sample of HA was placed in a flask. The flask was placed in a hot water bath until the sample vaporized. It was found that 1.18 g of vapor occupied 300.0 mL at 100°C and 1.00 atm. Determine the molecular weight of the acid. Show all work.

(d) Using your answer from part (a), determine the molecular formula for part (b) and for part (c).

(e) Account for any differences in the molecular formulas determined in part (d).

![]() Answer and Explanation

Answer and Explanation

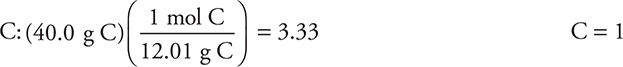

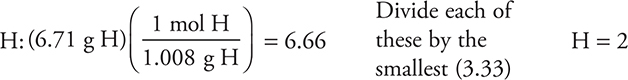

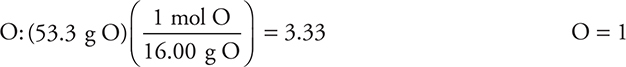

(a) The percent oxygen (53.3%) is determined by subtracting the carbon and the hydrogen from 100%. Assuming there are 100 g of sample gives the grams of each element as being numerically equivalent to the percent. Dividing the grams by the molar mass of each element gives the moles of each.

For

For

For

This gives the empirical formula CH2O.

You get 1 point for correctly determining any of the elements and 1 point for getting the complete empirical formula correct if you show your work. The symbols do not need to be in the order shown here.

(b) Using HA to represent the monoprotic acid, the balanced equation for the titration reaction is:

![]()

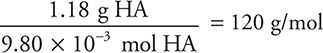

The moles of acid may then be calculated:

The molecular mass is:

You get 1 point for the correct number of moles of HA (or NaOH) and 1 point for the correct final answer, if you show your work.

(c) There are several methods to solve this problem. One way is to use the ideal gas equation, as done here. The equation and the value of R are in the exam booklet. First, find the moles: n = PV/RT. Do not forget that you MUST change temperature to kelvin.

The molecular mass is:

You get 1 point for getting any part of the calculation correct and 1 point for getting the correct final answer, if you show your work. If you used a different method and got the correct results you will still get credit.

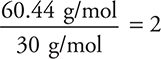

(d) The approximate formula mass from the empirical (CH2O) formula is:

12 + 2(1) + 16 = 30 g/mol

For part (b):

Molecular formula = 2 × empirical formula = C2H4O2

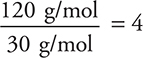

For part (c):

Molecular formula = 4 × empirical formula = C4H8O4

You get 1 point for each correct molecular formula. If you got the wrong answer in part (a), you could still get credit for one or both molecular formulas if you used the part (a) value correctly.

(e) The one formula is double the formula of the other. Thus, the smaller molecule dimerizes (forms a pair) to produce the larger molecule.

You get 1 point for pointing to any relationship between the two formulas. You get 1 point if you note the second formula is two of the lighter molecules added together.

Total your points. There are 10 points possible.

![]() Rapid Review

Rapid Review

• The mole is the amount of substance that contains the same number of particles as exactly 12 g of carbon-12.

• Avogadro’s number is the number of particles per mole, 6.022 × 1023 particles.

• A mole is also the formula (atomic, molecular) mass expressed in grams.

• If you have any one of the three—moles, grams, or particles—you can calculate the others.

• The empirical formula indicates which elements are present and the lowest whole-number ratio.

• The molecular formula tells which elements are present and the actual number of each.

• Be able to calculate the empirical formula from percent composition data or quantities from chemical analysis.

• Stoichiometry is the calculation of the amount of one substance in a chemical equation by using another substance from the equation.

• Always use the balanced chemical equation in reaction stoichiometry problems.

• Be able to convert from moles of one substance to moles of another, using the stoichiometric ratio derived from the balanced chemical equation.

• In working problems that involve a quantity other than moles, sooner or later it will be necessary to convert to moles.

• The limiting reactant is the reactant that is used up first.

• Be able to calculate the limiting reactant using the mol/coefficient ratio.

• Percent yield is the actual yield (how much was actually formed in the reaction) divided by the theoretical yield (the maximum possible amount of product formed) times 100%.

• A solution is a homogeneous mixture composed of a solute (species present in smaller amount) and a solvent (species present in larger amount).

• Molarity is the number of moles of solute per liter of solution. Don’t confuse molarity, M or [ ], with moles, n or mol.

• Be able to work reaction stoichiometry problems using molarity.

• Always use the balanced chemical equation in reaction stoichiometry problems.

• Watch your units. The mass of one substance will not cancel the mass of another substance. The moles of one substance will never cancel the moles of a different substance. A mole ratio is required.