Analysing English Grammar: A Systemic Functional Introduction (2012)

Chapter 2: The units of language analysis

2.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter, a distinction was made between structural and functional descriptions of grammar. It was suggested that a complete analysis must take a functional–structural view of language since these two components work together and are normally inseparable. Grammatical structure, including lexical structure, is what allows the functions to be expressed. So with this relationship between function and structure in mind, this chapter will take a deeper look at structure and offer some descriptions of the main grammatical units we will be working with.

This chapter offers a general overview of the clause and its internal composition. It also introduces the basic terminology and notation that will be useful for our exploration into analysing English grammar. The main idea presented here is that when a speaker says something about something, they are using language to describe (very loosely) a situation, and that this situation is represented in language by a structure called the clause. For now we can think of this structure as being very similar to our understanding of sentence in written language, as was explained in Chapter 1. The entities (the ‘something’) we want to say something about are seen as participating in the description of the situation. In this chapter we will begin to explore the relationship between the functions involved in the situation and the structures that these functions typically take.

2.1.1 Goals and limitations of the chapter

In my view, the nature of grammatical analysis is complex and it is this complexity that makes analysing grammar so challenging and interesting. Each chapter in the book tackles a different area of the grammar so that, as we go through the book, we will be progressively building up our view of analysing grammar. In doing so we will be piecing together the puzzle. This approach itself can be challenging because it means that it may leave you with a feeling of not seeing the big picture until we get to the end. From experience, by developing an approach to analysing grammar in stages, the methodology and strategies needed to work through the complexities of analysing grammar will become clearer and easier to do. As is always the case, we have to start somewhere, and in analysing language we have to impose an order to what we do and how we do it. This implies that there are different ways to do this and all analysts need to find the best way for them. However, a full analysis can’t really be done until a full view of the clause has been developed within the functional framework being presented here. I think we all experience some degree of frustration when learning a new analytical method because it is tempting to want to know everything all at once, but this would actually make things even more difficult. Instead, by working through the methodology in stages, the full view will be built up gradually. Consequently, some concepts and terminology may need to be mentioned before being fully explained at a later stage. This is especially true in this chapter because it attempts to provide a general overview of the clause and the main grammatical structures we will be working with, but without going into enough detail to really get a good understanding of them. However, this will come as we progress through the chapters.

2.1.2 Notation used in the book

It is standard practice in linguistics to use the asterisk, *, to indicate an unacceptable or ungrammatical structure. This practice is adopted in this book, and where an asterisk is used at the beginning of an example it will indicate that the example is not considered grammatical.

As stated in Chapter 1, certain specific terms will be written with an initial capital letter to mark that they differ in meaning and use in this specific context from more general meanings of the word in its common use. These include all of the functional elements of the clause. Structural units will not be capitalized nor will any other terms since this would become quite distracting, as there are so many words that have both a general and specific sense within functional grammar. For example the word ‘text’ as used in this book means any instance of language in use – or, in other words, the output from the language system, regardless of whether it is in print, electronic or spoken form. To note each specific term with a capital would almost certainly lead to far too many words being capitalized, so an effort is being made here to reduce the use of capitals.

The relationship between function and structure was introduced in Chapter 1 and explained as one of realization or expression: function (or meaning) is realized or expressed through linguistic structure. This section will introduce notation for referring to this relationship. In diagrams, this will be noted by a horizontal bar, – (as is used in written fractions), and in written form, for ease of typography, it will be noted by a vertical line, | (e.g. ‘function’|‘structure’). It is simply a way of indicating that a particular unit of linguistic structure is serving to express one or more functions.

One of the difficulties of dealing with a functional–structural approach to analysing grammar is learning the distinctions being made when wanting to focus on one or the other, because this means there is a need for terms to refer to the functions of grammar and different terms to refer to the structures of grammar. So, for example, in Chapter 1, the term ‘clause’ was used to describe the main (or largest) grammatical structure in English, and ‘situation’ was used to describe its functional or semantic role. Because there isn’t a one-to-one relationship between function and structure (e.g. a given structure may be used for a variety of functions), it is important to be able to discuss relevant features in either strictly structural terms or strictly functional terms, or even both at the same time.

This chapter also introduces the notation used in this book for tree diagrams which represent the functional–structural analysis of English grammar. In addition to the bar mentioned above to indicate the relationship of function and structure, the slash (a diagonal line), /, is also used to show cases where more than one function is mapped onto a particular structure. For example Subject and Theme, which are two functions that will be introduced later in the book, very often map onto the same structure, as is shown in Figure 1.6. The notation used to indicate this would be as follows: Subject/Theme. This will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.

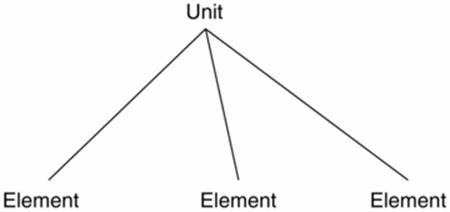

Tree diagrams are used in this book because they most accurately illustrate the complex relationships within the clause. In SFL, box diagrams are frequently used (as shown in Figures 1.6 and 1.7) but they often do not clearly identify the relationships between function and structure nor do they readily describe some of the interesting and sometimes complex relations within the clause. Many people find drawing tree diagrams useful from the analytical perspective because it forces you to actually work out the internal workings of the clause. There are two main principles of drawing tree diagrams. One is the use of nodes to indicate a single unit of structure and the other is the use of branches to indicate membership within a unit. This is shown in Figure 2.1, where the node is indicated by the point made where the branches (lines) join. All nodes are labelled by the unit being represented. Each branch is labelled with the elements which are being expressed in the unit of language being analysed. The structure and components of units will be presented later in this chapter and throughout the remaining chapters of the book.

Figure 2.1 Basic principles of a tree diagram

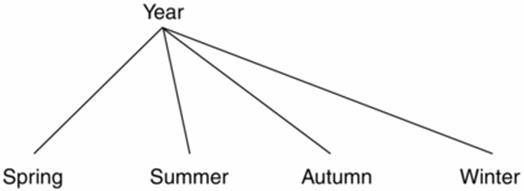

The principles of tree diagrams can work with almost anything. Figure 2.2 illustrates how a tree diagram could represent an analysis of the concept of

Figure 2.2 The components of the year as a tree diagram

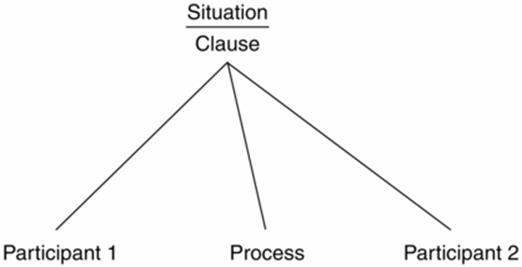

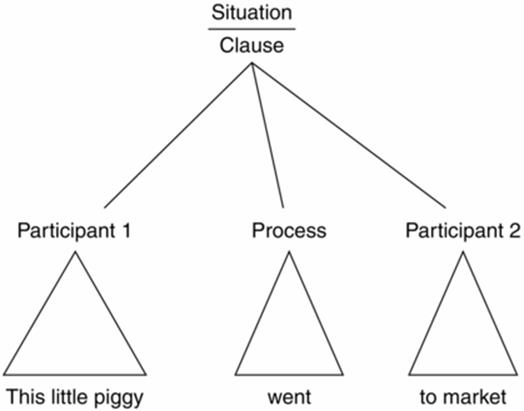

The main components of the clause can be represented in a similar way, using tree diagrams as shown in Figure 2.3. Due to the multifunctional nature of the clause, it is difficult to represent its structure without having first considered the various functions that it expresses; however, for illustrative purposes here, we can take a very general view of one function to show how the clause can be described in terms of its main components. Using the terminology we have developed so far, the diagram is saying that the clause has three components: one process and two participants. This very basic, generic structure is representative of the most common configuration of the English clause. For example, this could be the clause configuration for something like [the girl] [kicked] [the ball] or [the dog] [chased] [the cat].

Figure 2.3 Example of a general description of the clause as a situation

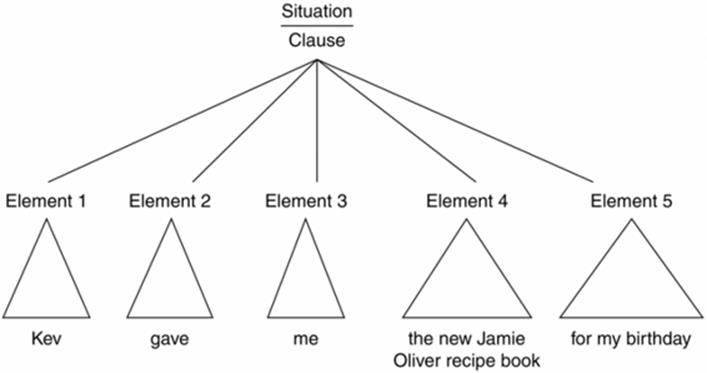

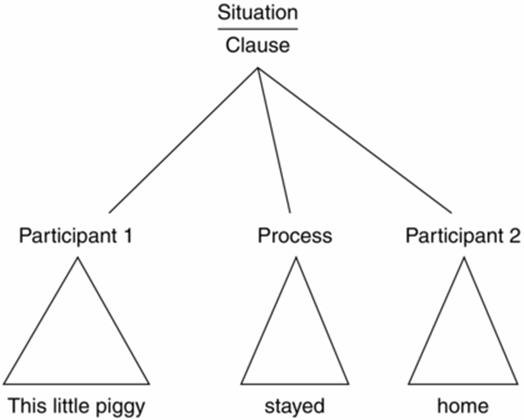

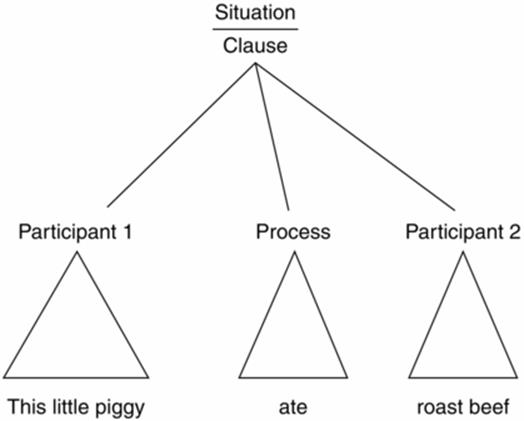

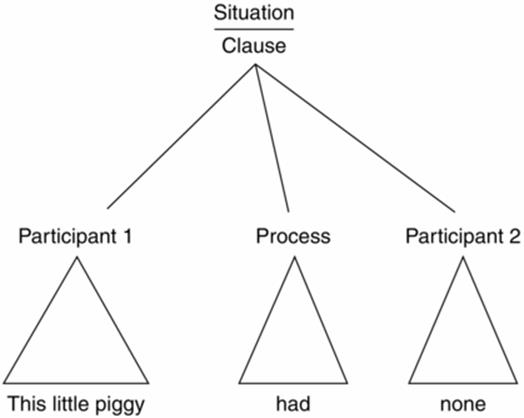

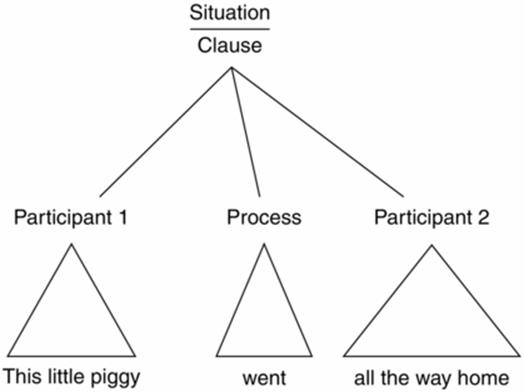

Finally there is one last symbol which is used in this book as notation. There are instances where the structural detail within the tree diagram is not being shown for some reason (e.g. further detail is not necessary for the current purposes or reducing the amount of detail is more appropriate to save time). In these cases, a triangle, Δ, is used rather than a line notation and it replaces all branching beneath the given node. This is illustrated in Figure 2.4, which shows example (4) from Chapter 1. Here the triangle notation is used rather than branching from each element (component) of the clause because at this point the detail has not yet been developed. By the end of Chapter 7, all detail in the analysis of the clause will be able to be included.

Figure 2.4 Use of triangle notation to replace branching in tree diagrams

The notation presented above is just a starting point; more detail and notation will be added throughout the remaining chapters as needed. The rest of this chapter focuses on providing a general view of the clause and the various units involved in its composition.

2.2 The clause: elements and units

Language can’t be analysed whole; it has to be segmented in some way to make it manageable. This could be as individual words, as a section of speech, as sentences or even longer stretches of language. For grammatical analysis, most linguists agree that there is a unit of language called the clause, which corresponds roughly to the unit of sentence in written language. If this is true, you might be wondering why we aren’t interested in studying the sentence. The sentence in English is generally accepted as an orthographic convention, something that has developed in the writing system along with punctuation. There is no equivalent marked unit in spoken English, where recognizing the units of grammar is challenging and requires some understanding of tone patterns and pausing as well as grammar. So it is problematic from an analytical perspective to rely on the sentence as the core unit of interest because it restricts us to written texts and it does not help us when we are interested in texts without punctuation, such as spoken language or some forms of electronic language.

If we come back to the idea that the sentence is close to a core grammatical unit, we begin to get a sense of the unit we are trying to describe. But our main problem is that it is nearly impossible to define a clause. To the best of my knowledge, there is no existing (satisfying) definition. The challenge is due to the fact that while there is considerable regularity in the main components of the English clause, there is also considerable variation. Consider the following short text, which is an email from an adult daughter to her mother.

Text 2.1 Personal email text

Hi Mom,

We’ll be going to Scotland from March 30 to April 2nd. We’ll go to London April 14th. It’s a nice day here too. John has taken Tom to the dentist for a check-up, we’ll see if he agrees to open his mouth!!

This short text has four sentences which are clearly recognizable by the punctuation (if we exclude Hi Mom). Almost every one of these corresponds to a single clause as we will see shortly, but we first need to know what a clause is before we can identify it. A full description of the clause is not going to be developed until much later in the book. So in the meantime we need some working guidelines in order to begin the analysis. The clause can be thought of as a structural grammatical unit that expresses a given situation. A situation can be thought of as similar to the everyday meaning of the word: ‘a set of circumstances; a position in which one finds oneself; a state of affairs’.1 In functional terms, it describes or relates a particular process (what is going on) and particular participants (one or more individuals or objects that are involved in the process). This description of situation will be presented in more detail in Chapter 4.

The sentences in the text are listed below as examples (1) to (4). The first two sentences in the text above, shown in (1) and (2), each express a situation where someone (we) is going somewhere (Scotland and London). In (3) the situation is one of something being something (i.e. ‘today is a nice day’). Sentence (4) is more challenging because it is difficult to determine what the situation is because of the number of verbs. Although we would all agree this is one sentence based on the punctuation, there seems to be more than one situation being expressed.We might argue that in fact if we replaced the comma with a full stop after the word check-up, we would have two sentences. This is true and certainly this would work as shown in (5) and (6) below. However, this only solves the problem for the new sentence (5) and we still can’t be sure about the situation being expressed in (6). This is because two processes are being described: seeing and agreeing.There is a subordinate clause in example (6), namely, if he agrees to open his mouth. However, the tools needed to confidently determine the clause boundaries have not yet been developed (i.e. whether sentence (6) is in fact one clause or two). This isn’t something we can resolve now because we need more information about how to determine clause boundaries. We will come back to this later in the chapter once we have developed some initial strategies for identifying a situation.

(1) We’ll be going to Scotland from March 30 to April 2nd

(2) We’ll go to London April 14th

(3) It’s a nice day here too

(4) John has taken Tom to the dentist for a check-up, we’ll see if he agrees to open his mouth!!

(5) John has taken Tom to the dentist for a check-up

(6) We’ll see if he agrees to open his mouth!!

What we want to focus on here is an understanding of what we mean by a clause. For our purposes, we will define clause as the linguistic (grammatical) resource for expressing a situation, which describes who or what is involved and what kind of relation or activity is involved (a process and the participant(s) it involves). This is still somewhat vague but we will have developed a better view of the clause after reading through Chapters 4 and 5. The core elements of process and participant can be illustrated with example (1) above. This clause represents a particular situation: in other words, someone is going somewhere. The entities (who or what) participating in any situation are referred to as participating entities or simply participants. A participating entity (or participant for short) in this sense includes any entity (person, object, place, idea, concept, etc.) that participates in completing the process. In example (1), although we do not know who exactly is involved, we do know that the ‘someone’ who is going is the speaker and some others, which is indicated by the use of the pronoun we. We also know that the ‘somewhere’ participant (a location) is given as to Scotland. The relation or activity represented in the situation is referred to as the process. In example (1), as we have already said, the process is one of ‘going’. We can now begin to describe the situation in example (1) as a process of ‘going’ with two participants. This leaves us with a bit of language left over: from March 30 to April 2nd. Clearly, in the context, this information is very important to the speaker and addressee. It is within the boundaries of the clause and offers an additional description to the situation, namely when precisely the event will occur. This kind of descriptive information is considered optional in functional grammatical terms because the only parts that are expected within the language for this particular situation are the process and two participants: one participant who is the one who is going and a second participant which is the location of where the first participant is going. The other information included in this situation doesn’t have to be there in order to meet the expectations of the language (in other words, no speaker will find it missing any content if it isn’t included). For now we put this to the side temporarily so that we can focus on the core elements of the clause, and we’ll come back to it briefly throughout this chapter and in detail in Chapter 4.

In this discussion I have been switching back and forth between functional elements and structural units. This is because they are expressed simultaneously. In other words, there can be no expression of a functional element without some structure. Each situation is realized through the unit of the clause. We can represent this using notation to show this relationship by using a straight line (either vertical or horizontal) as follows.

situation | clause

situation

clause

The linear form (the first one above using a vertical bar) will be used when referring to this relationship in text: situation|clause. The second form is used in diagrams following conventions in SFL. This will become clear as the notation is used in examples.

Each clause is a constellation or configuration of component parts which express various functional meanings, which will be referred to as elements, and these component elements are realized or expressed through various different structural units. These structural units will be described in section 2.3 below. As we saw in Chapter 1, the clause expresses three main functions (called metafunctions), and these will be discussed in detail in Chapters 4, 5and 6. For now, we want to think of the clause as the linguistic realization of the situation that the speaker wants to express, and that the clause is made up of component parts that fit together.

So far, the only parts we have mentioned are the very general functional labels of process and participant. In this chapter, we will not describe the functional elements in any detail since, as stated above, this will be covered in Chapters 4, 5 and 6, each detailing one of the three main metafunctions of the clause. The focus here will be on the structural units which give the clause its shape. Functional elements are usually realized through group structure (i.e. a group of words). There are some cases where a particular functional element is realized by a single word (lexical item) rather than a group. For example, let’s consider the clause in example (7) below, which is just an invented example for the purposes of illustration.This clause relates a particular situation and it is composed of four parts as follows: but / the boy / doesn’t know / the answer.

(7) but the boy doesn’t know the answer

The clause is representing a situation of someone knowing (or not knowing in this case) something. There are two participating entities: the boy and the answer. Each of these expressions consists of more than one word which work together to express the Participant. We can prove this by asking questions about this situation. If I asked ‘Who doesn’t know the answer?’, someone would reply ‘The boy’. So we can be confident that these two words work together as a group to express the first participant in this situation. This is also true for the second participant, and I could ask ‘What doesn’t the boy know?’ and the reply would be ‘The answer’. In fact, the segmentation of the clause into four parts shows that, most of the time, each part includes more than one word working together in this way. However, the first section of the clause has only one word, the conjunctive word but. Its function can be seen primarily as linking this clause with another part of the text since the use of but in English always assumes a connection to something already said. This function will be described in Chapter 6. In this example, we would say that butis not seen as a group because there are no other words in the language that can work with it, so it does not have the potential to expand to a group. Instead this first element is seen as being realized by a single lexical item (i.e. not a group or phrase).

2.2.1 Units of the clause

When we talk about the units of the clause, we are referring to the grammatical structures which combine to form it. The challenge in analysing grammar in a functional framework is working out the relationship between the functional elements and the structural units. As we saw in Chapter 1, the approach to the clause in SFL is multifunctional; in other words, the clause itself and its elements may express more than one function at the same time. These different functions can be considered as different views of the clause (as in Chapter 1, section 1.3).

In analysing a clause, the first job for the analyst is to segment the clause into identifiable units. The main grammatical units found within the clause are described in section 2.3 below. At this point, a few basic notions will be covered before moving on to the individual groups.

Basic notions

· Every text contains at least one clause.

· The clause is made up of units.

· Each clause has one and only one main verb.

These are very useful guidelines for the analyst. If the main verb can be identified, then finding the clause boundaries is much easier. The main verb is the key to understanding how the clause works because it expresses the main process represented in the situation. As we will see in section 2.4, once we have worked out what the process is, we can use some tests to determine what participants are included in the situation. This in turn will help us to identify the relevant structural units expressed in the clause.

The main problem is that finding the main verb can be challenging, and this is due in part to the way the verb system works in English. Chapter 5 will describe the verb system in detail, but for now it is enough to continue with our discussion of the clause and its composition. In this section, I want to point out the main complexity in working with English grammar, which is the frequent use of embedding. Embedding simply means that the language lets us insert units inside other units and this is what makes it so difficult to identify them. To better understand this, we’ll take a look at a famous example from a children’s story, ‘The House that Jack Built’. In this story, a funny tale is told by playing around with embedding. The story starts off with a very simple clause and each successive clause embeds something from the previous clause in the story. I won’t retell the whole story but, just to give you an idea, here’s how it begins (although there are many different versions of this tale).

The House that Jack Built

This is Jack.

This is the house that Jack built.

This is the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.

This is the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.

This is the cat that chased the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.

This is the dog that scared the cat that chased the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.

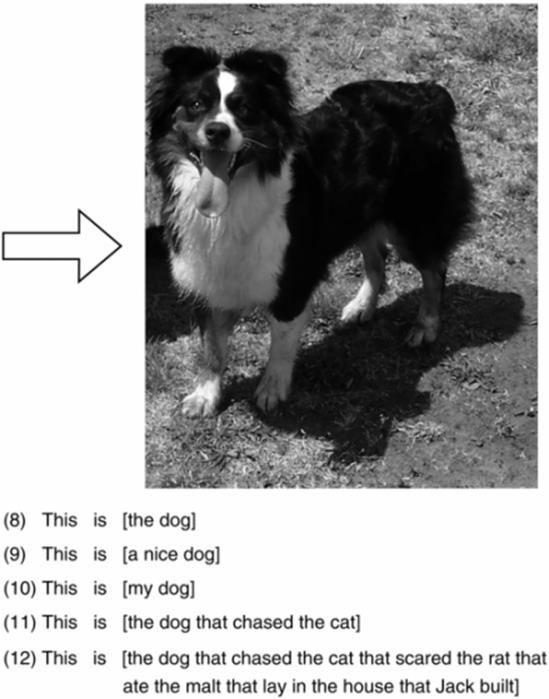

The kind of embedding shown in this text is very common in English but it can make analysing language very challenging at times. In each of the clauses listed above in the ‘House that Jack Built’ story, a different entity is being identified: first it is a person named Jack, then a particular house, and then some malt, and so on. If we take for example the clause which is introducing a dog and consider the different ways in which this could be done by the speaker, we should get a sense of the slots or components involved in expressing one particular situation. All the clauses listed in Figure 2.5 represent the same situation but they differ in terms of the grammatical structure and the description of the second participant (the dog). This is illustrated visually with an arrow, which is meant to indicate this is and a photograph of a dog to represent the actual referent being talked about.

Figure 2.5 Simple clause, this is [

Examples (8) to (12), shown in Figure 2.5, illustrate some of the different ways the dog in question can be referred to. Examples (8) to (10) would be considered relatively simple expressions but (11) and (12) involve embedded units. In these two cases we find clauses inside the expression used to refer to the dog and they serve to offer a full description of the dog (so it’s not just any dog but the one that chased the cat, for example, and not just any cat but the one that scared the rat, etc.).

The last example in Figure 2.5, example (12), illustrates the problem of identifying the main verb in a given clause. It is easy to do in (8), for example, because there is only one verb in that clause and this is the verb ‘be’ (is in this case). However, in example (12), there are a total of six verbs: is, chased, scared, ate, lay and built. There are ways to reduce the complexity in these cases. For example, the entire expression used to refer to the dog in example (12) (i.e. the dog that chased the cat that scared the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built) can be replaced by it. This should eliminate some of the challenges because it shows that all of the verbs in that section of the clause are there to describe which dog is being talked about and consequently they are not there to express the process. Section 2.3 below presents a brief overview of lexical classes, which will help to remind readers how to recognize verbs. Chapter 5 will discuss the verbal system in some detail, providing the information required to be able to confidently recognize main verbs and clause boundaries.

When beginning to analyse a clause the key is to be able to identify the main verb because so much of what is expressed within the clause is organized around it.

The main verb expresses the process (i.e. what’s going on). In addition to the process, the clause may also contain participants (who or what is involved). It may also include other descriptive information called circumstances (for example information about how or why the process is taking place) – see Chapter 4. The clause is the central unit in analysing grammar because it is the grammatical resource for expressing a particular situation. The key point of entry to identifying the clause is by its required main verb, which links it to the situation that is being represented by the clause.

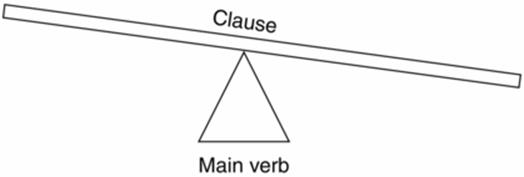

When we say that the clause has only one main verb, this does not mean that each clause has only one verb. A clause can combine verbs in various ways. For example, I could say: I might have been sleeping. This clause is almost exclusively expressed by verbs and they are underscored in the example. Nevertheless this situation is about someone sleeping and the main verb is ‘sleep’. The remaining verbs contribute towards the meaning of the process in terms of when in time the participant was sleeping and also the degree of certainty about the process. The way verbs combine in English is another reason why working with grammar can be so challenging. It can be very difficult to confidently identify the main verb in a clause; it takes practice. Words alone are not enough, as shown in examples (13) and (14).Each of the clauses in (13) and (14) expresses a situation. The first step to analysing the clause is by locating the main verb. In a sense the main verb is the pivotal element of the clause, as illustrated in Figure 2.6. The analysis of the clause hinges on the main verb since it is by identifying the main verb that the process can be determined, and then the rest of the analysis unfolds from this.

(13) Time flies like an arrow

(14) Fruit flies like apples and bananas

Figure 2.6 Main verb as pivotal element of the clause

In (13) the main verb (the only verb) is fly and in (14) the main (and only) verb is like. Consequently each verb expresses a different process and we can describe each clause very generally as follows. The clause in (13) expresses a situation of flying where time (participant) is flying and this process of flying is being described as happening in the same manner as an arrow flies. The clause in (14) expresses a situation of liking where fruit flies(participant) are said to like apples and bananas (participant).

There is a trick to working through these two clauses because the same two adjacent words (flies and like) appear in each clause and it isn’t immediately obvious which one of these is the verb in each case. In the next section, groups and word classes are presented. This includes an overview of the main word classes such as noun, verb, preposition and adjective as well as the different types of groups (grammatical word groups) which we will be using in the description of English grammar.

2.3 Word and group classes

In some analytical frameworks a distinction is made between two types of unit: a phrase and a group. This is a theoretical distinction and not everyone is in agreement on the distinction. For Halliday and Matthiessen (2004: 311), the terms phrase and group are not equivalent: ‘a group is an expansion of a word, a phrase is a contraction of a clause’. In this view, the clause is considered a full phrase rather than a group since it is not based upon the expansion of a particular word or class of word. The special status of the clause as compared to other types of unit is generally accepted. The notion of group centres on the concept of headedness – in other words, each group is based on a pivotal element, such as a noun, a verb or an adjective. Halliday’s notion of expansion is important. For each type of head – whether a noun, a verb or whatever – there is the potential for expansion through modification (modification in this sense can be thought of as an elaborated description).

In the previous section, I mentioned that finding the main verb in a clause is difficult because verbs are combined in English to modify the core meaning of the verb as in the example given above, might have been sleeping. However, it is clear that these verbs are working together as a unit, or group, in order to alter the meaning of ‘sleep’ as the event in a particular situation.

Before explaining the concept of group and how it is used in this book, the next section provides a brief overview of word classes for those who want to be reminded about nouns, verbs, adjectives and other word classes. Having a good understanding of this kind of classification is important because, in general, the concept of group and group structure is based on word categories.

2.3.1 Lexical categories (also known as word classes)

Certain types of words behave similarly enough to be grouped in the same word class. These classes are not strict with clear boundaries since some words in a given word class may not behave identically to all other members of that class. For every word class there tends to be a typical member of that class that can be thought of as the prototypical member, which displays all the important features of the class. There will also be members that only share some of these features. Before giving an overview of the main grammatical groups, we will review the main word classes. For many readers this will be familiar ground.

Let’s start with a little experiment about words.

Say the first word that comes to your mind.

What word did you think of first?

Psycholinguistic research shows that if you ask most people to say the first word they think of, they will usually say a word that is a noun. Noun is perhaps the word class that most people can identify with most easily. It is often the easiest class of word for children to learn as they begin to speak. In school most of us were told that a noun is a person, place or thing. This is a very vague definition but it works as long as you can understand that ‘thing’ can mean anything whether it is real or imaginary, including feelings, thoughts and abstract concepts such as jealousy, happiness or love.

In analysing language, it is convenient to be able to group words in this way so that we can use a term, such as ‘noun’, to refer to a set of words that are similar in most ways and that have similar properties. This does not mean that this is how words are organized in the language system or indeed in our brains. In fact, we are pretty sure that they are not organized by classes but rather in networks that connect the meaning and forms (e.g. sound form or written form) by various types of associations. So the terminology used in this section is more a matter of convenience and we are not attempting to describe the way language is really organized in the brain.

2.3.1.1 Nouns

Nouns are words used by speakers to denote objects in our world, including ones that are real, imaginary, concrete or abstract. Nouns can be sub-classified based on features such as mass or count, which explains distinctions between nouns such as flour, sand or water, which are mass nouns, as compared to nouns such as egg, shovel or pin, which are all count nouns. These two sets of nouns behave differently in the grammar. For example in English it is acceptable to say I need flour in the recipe but not *I need egg in the recipe. Similarly, with a non-specific or indefinite reference such as in I have a shovel, the indefinite article, a, is required for count nouns but with mass nouns the indefinite article is not acceptable, *I have a sand.

There is also a distinction to be made between what is called common and proper nouns. Proper nouns are actually names and these are used by speakers to refer to a specific person or place, such as John, Toronto, Buckingham Palace. Common nouns are all other nouns. Most often, there are grammatical differences between proper nouns and common nouns because proper nouns (since they are names) are not usually modified or described in any way. For example, it would sound very odd indeed to hear someone say *I went to a nice Toronto for two weeks. In this sense, proper nouns are much more like pronouns than common nouns. However, you might hear someone say something like you aren’t the John I know. In this case, the speaker isn’t using John as a proper noun to name and refer to a particular person. John is being used here as a common noun. What we mean by common noun is a word that is recognized by speakers to denote a particular class of entity. So, in this particular use of John, the speaker isn’t referring to a particular person named John, but rather a class or set that includes all the possible Johns. A similar thing happens when we talk about ‘keeping up with the Joneses’.

In some cases, a noun has been derived from a verb. This process is called nominalization. These derived nouns are abstract common nouns and they function the same way as other common nouns. However, they seem to retain much of the meanings from the associated verb. For example, the noun evaluation carries with it the meaning that someone evaluated something. While these types of noun can be significant in certain kinds of analyses, as a lexical item, they behave as normal common nouns and display the same features as summarized below.

In discussing what it is for a word to be a noun, we’ve also seen examples that illustrate how nouns behave. There are three main ways in which we can readily identify a noun.

1. Nouns are the only kind of word in English that are affected by quantities – they can be made plural or singular (e.g. evaluation – evaluations).

2. Nouns are affected by definiteness – they can be made definite or indefinite by different determiners (e.g. the apple – an apple).

3. Nouns can be modified in their description – they can be extended into a group, most often by an adjective (e.g. the juicy apple – the red apple in the fridge).

2.3.1.2 Pronouns

Usually the class of pronouns is included in the word class of noun but this hides a major difference in how they work in the language. Clearly, there are significant similarities in terms of how they are used by speakers but pronouns are not simply another kind of noun. In fact, the similarities between pronouns and names (proper nouns) are considerable and there are some good reasons for grouping these two categories together. It isn’t so important how they are grouped but it is important to be able to recognize a pronoun.

You may have been told in school that a pronoun replaces a noun. This isn’t actually true. This point will be made clearer in the next chapter but for now a simple example should illustrate what I mean. If someone wanted to tell you something about a particular dog, they might say something like this (the nouns are underscored): That black dog came into my house yesterday. If I wanted to say more about this dog and include what it did in my yard, I would say something like the following, where the pronoun is double underscored: and it knocked over my plant. However, if the pronoun it were to really replace the noun dog, the clause would have to become: *and that black itknocked over my plant. What this shows is that, when a pronoun is used, it does not simply replace a noun. A pronoun is used to replace the full expression being used to refer to some object. In technical terms, a pronoun functions in the same way as a group and not as a word. This is the main difference between nouns and pronouns. Nouns do not actually refer to an object in and of themselves; they denote (or represent) objects in the language system. They must be incorporated into an expression (a nominal group) that a speaker uses to refer to an object. Pronouns, on the other hand, work differently. They have no inherent meaning of their own; their meaning is always by reference to something said elsewhere in the text or by reference to something known (for example by pointing at a person and saying he as in he looks bored).

Like nouns, there are various types of pronoun and each type fits into the grammar in a slightly different way.

Personal pronouns

Personal pronouns are used to refer to living things with the exception of the special pronoun it, which can refer to anything at all in the singular. Recognizing personal pronouns is easy because we don’t have very many of them. They are further grouped by sex and number as shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Personal pronouns in English

|

Subjective |

Objective |

Possessive |

Reflexive |

|||

|

1st person (self-reference) |

singular |

I |

me |

determiner |

my |

myself |

|

absolute |

mine |

|||||

|

plural |

we |

us |

determiner |

our |

ourselves |

|

|

absolute |

ours |

|||||

|

2nd person (addressee reference) |

singular |

you |

you |

determiner |

your |

yourself |

|

absolute |

yours |

|||||

|

plural |

you |

you |

determiner |

your |

yourselves |

|

|

absolute |

yours |

|||||

|

3rd person (other person reference) |

singular |

she/he/it |

her/him/it |

determiner |

her/his/its |

herself/himself/itself |

|

absolute |

hers/his/its |

|||||

|

plural |

they |

them |

determiner |

their |

themselves |

|

|

absolute |

theirs |

|||||

I’ve used the terms ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ to refer to the distinction between grammatical uses of the personal pronouns. Many use the terms ‘nominative’ and ‘accusative’ but I think these are not as transparent as ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’. These terms are used to indicate the distinction for example between I and me, which has to do with the grammatical position of the pronoun in modern English. Subjective pronouns are used in the Subject position of the clause whereas objective pronouns are used in Object (or Complement) position in the clause. Where the first person (or self-reference) pronouns are concerned, there is currently considerable variation in use and it has become relatively common to hear objective pronouns in Subject positions, especially with conjunctions (e.g. John and me went out last night). This variation does not happen with third person pronouns in standard English (the second person pronoun forms are identical so there would be no difference to notice). Table 2.1 is not a strict description of how speakers use personal pronouns but rather a description of the different classes of personal pronouns; different varieties of English may distribute the pronouns differently.

Possessive pronouns mark a relationship of possession, ownership or association between two objects (referents): e.g. Does Steven like his teacher? In this example, his refers to

Relative pronouns

Relative pronouns have a double duty to perform: part pronoun and part conjunction. They work as pronouns in the sense that they refer to some object (person or thing) that has already been mentioned in the text, except that with relative pronouns the referent is mentioned within the same clause. They are also like conjunctions because they serve as a link between a main clause and an embedded clause by marking the introduction of the embedded clause. This is illustrated in example (15), where the relative pronoun is underlined.The most common relative pronouns are who, that and which, but the full set includes: that, which, who, how, whose, whom, where and when. These pronouns show up in different places in the grammar. For example that is also a demonstrative pronoun and who, along with all the other so-called ‘wh’ words (including how), is an interrogative pronoun (e.g. How are you? Who are you? Where are you?). It is important to be able to recognize how the word is functioning depending on what it is doing in the clause.

(15) It was just a thought that crossed my mind

Deictic (demonstrative) pronouns

There are four deictic pronouns in English: that, this, these and those. A deictic word is a word that gets its meaning from a shared context. If I were to say, for example, that is beautiful, it would be impossible to know what I was talking about unless the person I was speaking to could figure out what that meant or what the referent for that was (e.g. something I am pointing at). This use of these words sees them working as true pronouns since they replace the full expression. For example, if I had been referring to a particular table when saying that is beautiful, then I really would have been saying that table is beautiful. Note that in this last example, that in that table has the same function as the article the. Once again, this shows that word classes are not fixed groups; words vary in the ways that they can be used.

Indefinite pronouns

The words that are grouped under the heading of indefinite pronouns are varied and include words that have no specific referent, such as anyone or somebody. In a way this is a catch-all category for words that are used to refer to vaguely specified or unspecified objects (e.g. something) or to unspecified amounts or quantities (e.g. all, many or everything). Many of them include both kinds of meaning: non-specific reference and non-specific amount. It is debatable whether or not they are truly pronouns in the way we have been discussing them here. Most of the indefinite pronouns are historically noun bases which over time fused to form one single word (lexical item), e.g. some thing ![]() something; any body

something; any body ![]() anybody. So they are not really pronouns in the strict sense of the word, although some would argue that these forms have become grammaticalized as pronouns. There is considerable variation with these forms and, as with many of the kinds of words we have been discussing, some of them can work as nouns: for example a nice little something. They border the two word classes of noun and pronoun because, on the one hand, they tend to be substituted for a full description and they tend not to be altered by plural, modifiers or determiners (e.g. *I haven’t seen the anybody). However, this may well be because plurality and definiteness (or indefiniteness) is encoded in these words already. For example, anybody was originally any + body. The word any includes meanings of indefiniteness (non-specific) and amount (unspecified amount but greater than zero). There is a difference though between nobody as a noun and nobody as an indefinite pronoun; the meanings of nobody are different in each case. The word nobody can be used as a noun as in a silly nobody like him, where it denotes a person who is insignificant. It can be used as a pronoun as in nobody was here, where nobody could replace a full expression such as your friends (i.e. your friends weren’t here). Even as pronouns, these words have considerably more semantic content than other types of pronouns. Usually the use of pronouns requires reference to information that is either already known or information that can be retrieved from the situation or context. In this sense they are stand-alone forms with respect to meaning.

anybody. So they are not really pronouns in the strict sense of the word, although some would argue that these forms have become grammaticalized as pronouns. There is considerable variation with these forms and, as with many of the kinds of words we have been discussing, some of them can work as nouns: for example a nice little something. They border the two word classes of noun and pronoun because, on the one hand, they tend to be substituted for a full description and they tend not to be altered by plural, modifiers or determiners (e.g. *I haven’t seen the anybody). However, this may well be because plurality and definiteness (or indefiniteness) is encoded in these words already. For example, anybody was originally any + body. The word any includes meanings of indefiniteness (non-specific) and amount (unspecified amount but greater than zero). There is a difference though between nobody as a noun and nobody as an indefinite pronoun; the meanings of nobody are different in each case. The word nobody can be used as a noun as in a silly nobody like him, where it denotes a person who is insignificant. It can be used as a pronoun as in nobody was here, where nobody could replace a full expression such as your friends (i.e. your friends weren’t here). Even as pronouns, these words have considerably more semantic content than other types of pronouns. Usually the use of pronouns requires reference to information that is either already known or information that can be retrieved from the situation or context. In this sense they are stand-alone forms with respect to meaning.

2.3.1.3 ‘One’

The lexical item one is listed separately here because traditionally it is included among the pronouns but it has uses that make it slightly different from the other pronouns. As a true pronoun, one is an indefinite pronoun because it does not refer to a specific person (i.e. one meaning anyone). This form is dropping from use. It is rare to hear someone say something like one shouldn’t eat too much meat. It would be more common now to say you shouldn’t eat too much meat. So you has largely replaced one as an indefinite pronoun.

It also has another use which is very much like a pronoun but which differs from all others in the sense that it actually does replace a noun. It is like a pronoun in the sense that its meaning is recovered by making the link to something already said in the text or something known from the context or situation. In example (16), it is clear that one is substituted for medication. What is different here as compared to pronouns is that in this example the speaker is referring to two different objects (i.e. two completely different medications) and not the same object as would be the case with a personal pronoun. This distinction is shown in example (17), where it and the expression the new medication refer to the same object.Although nouns and pronouns do share some features, the distinction isn’t always clear and some of the classification problems discussed above demonstrate that clear-cut boundaries around word classes are rather artificial. We should expect the boundaries to be fuzzy at best.

(16) I haven’t started on the new medication as I will use up the old one first

(17) I haven’t started on the new medication but I will start it tomorrow

2.3.1.4 Verbs

The class of verbs includes words that express an event (i.e. a relation or happening). This can be an event which is very active such as he kicked the ball or something that expresses a relation, as with the copular verb, be, as in he isa lawyer. The range of types of event is very broad and the various types will be covered in Chapter 4. These words differ from other word classes because they have different forms for past and present: for example, the dog chasesthe cat regularly [present] vs. the dog chased the cat regularly [past]. This can often be the distinguishing feature between words that look identical to verbs, as in the case of love: he loves her [verb] vs. his love for her was not strong enough [noun]. We can be certain that in the first instance love is a verb because the verb would change forms in the past: he loved her.

There are various ways to sub-classify verbs and perhaps the most essential distinction is between auxiliary verbs and what are commonly called main verbs, or lexical verbs to be more technical. Main verbs express the type of event and carry the meaning of the event, whereas auxiliary verbs work in support of the main verb to express different meanings related to the event. For example, auxiliary verbs can be used to express a particular aspect of the main verb in terms of its duration in time, regardless of whether the reference point is in the past, present or future (e.g. he is meeting a client now vs. he is meeting a client tomorrow). Auxiliary verbs can also be used to express doubt or certainty with respect to the main verb. It is important to understand how verbs combine in English because in many cases it is through certain combinations that these various meanings are expressed (this will be explained in detail in Chapter 5). For any such combination, there can only be one main verb although there may be several auxiliary verbs. Auxiliary verbs never appear on their own; they always work with a main verb. However, be, haveand do can be both main verbs and auxiliary verbs (will and get also have this variation but for different historical reasons). Recognizing the distinction will be explained in Chapter 6 although, given the properties of auxiliary verbs explained below, it should be fairly straightforward to recognize whether one of these verbs is being used as an auxiliary verb or a main verb. The important thing to understand about auxiliary verbs is that they adhere to very specific rules in English, which is explained briefly in the following list of the standard auxiliary verbs.

Progressive auxiliary verb

There is only one verb in English which can be used as a progressive auxiliary verb and this is the verb be. It is often referred to as the ‘be + -ing’ form because any verb following the progressive auxiliary, be, will be in the progressive form (or the present participle) – in other words, this verb will end in ‘-ing’. It doesn’t matter whether the verb following the progressive auxiliary is another auxiliary or a main verb: I was going to Spain, I might be going to Spain, the boy was being bitten by ants. The use of the progressive auxiliary is generally used to represent the event as ongoing or in progress, such as I am eating my lunch, which means that the event of eating is ongoing and not completed.

Perfective auxiliary

This perfective auxiliary is always expressed in English by the verb have. As with all auxiliary verbs, the perfective auxiliary determines the form of the following verb and forces it to take the past participle form, which can be referred to as the ‘-en’ form of the verb because of the ‘-en’ suffix on irregular verbs such as eat (eaten). In other words whenever have is used as an auxiliary, the next verb following it will always be in past participle form. This means that we can retrieve the past participle form of any verb simply by placing have before it. Being able to recognize the past participle is also important in the formation of passive verb constructions, as we will see with the passive auxiliary below. The have auxiliary combines with another verb to express the speaker’s perspective on the event in terms of having been completed with respect to some point or period in time, such as I had eaten my lunch before you arrived. Perfective forms are usually seen in contrast to the progressive. However, they can combine in both past and present forms or with modal auxiliary verbs (see below), as in I had been sleeping when the alarm went off.

Passive auxiliary verbs

There are two passive auxiliary verbs, be and get. The use of this auxiliary is slightly more complex in some ways than the progressive auxiliary. This is because its use changes the voice of the clause from active to passive and as a consequence the grammatical structure and meaning of the clause shifts. In the example given above involving ants, the main verb in the clause is bite but notice that in the clause, the boy was being bitten by ants, the Subject, the boy, is not the participant doing the biting. We know that, in this case, the ants are biting the boy. The active form would be: ants were biting the boy. There are two auxiliary verbs in the passive example (the boy was being bitten by ants) and they are both be, but the first one is the progressive auxiliary and we can tell this because the following verb is in the progressive form (being). The second auxiliary is the passive auxiliary be. It is this auxiliary that tells us that the boy is not doing the biting but rather he is being affected by the event of biting (by the ants). The form of the main verb bite is the past participle form of the verb. This is always true of the passive auxiliary; the following verb will always be in the past participle form, irrespective of whether it is another auxiliary verb or the main verb.

Support auxiliary verbs

English has a special auxiliary verb, do, which supports the main verb to form interrogatives (e.g. Do you like pizza?), negatives (e.g. you don’t like pizza) and tag questions (you like pizza, don’t you?) or to express emphasis (e.g. but you do like pizza). The do auxiliary verb cannot occur with any other auxiliary verbs; in a sense it replaces all others.

Modal auxiliary verbs

Modal auxiliary verbs are distinct from other verbs since they only have an auxiliary use and they do not have the same range of forms as do all other verbs (e.g. there is no past participle form for modal verbs). However, they overlap with do in the sense that they can be used to form interrogatives and negatives. The set of modal auxiliary verbs includes: can, could, shall, should, may, might, will, would and must. The modal verbs express a range of meanings that relate to the speaker’s view or opinion about the event. Traditionally these meanings are divided between epistemic meanings (probability related) and deontic meanings (obligation related). The modal auxiliaries can combine with all other auxiliary verbs except do in expressing the event, as is shown in example (18).

(18) I might[mod.] have[perf.] been[prog.] being[pass.] tricked[main verb] by that guy

2.3.1.5 Adjectives and adverbs

The classes of adjectives and adverbs have been grouped together here because of how very similar they are and the fact that historically adverbs in English were inflected forms of adjectives. Both are used as properties to describe or modify things and events. The distinction between the two relies on whether the properties concern a noun or a verb. Adjectives can be seen as properties of nouns, whereas adverbs generally modify verbs (although they are used for other purposes as well). In some cases there are adjective plus adverb pairs which are distinguished by the morpheme ‘-ly’, as in quick – quickly or happy – happily. For both classes, identifying members is usually done by testing the word for the main properties of this word class. There are two main tests:

· Can the word be modified by very, as in very quick or very quickly?

· Can the word be made comparative, as in quicker, happier, faster, more quickly?

2.3.1.6 Prepositions

Prepositions are words that typically indicate direction of some kind usually in relation to a nominal group, such as in the box, on the table, behind the chair, around the tree. They sometimes appear on their own without the nominal group to indicate the direction or location: for example, I’ll take this coffee up to my father now. Prepositions combine with other words such as nouns and verbs to create new words, such as upstairs, back-up or understand. Prepositions can be recognized generally by whether or not the word right can modify it; in general only prepositions can be modified by right in standard English (cf. the colloquial usage of right meaning very as in He was right pleased about that, which has a different sense). For example, right could appear before each of the prepositions given in this paragraph: right in the box, right on the table, right behind the chair, and right around the tree.

2.3.1.7 Articles and numerals

The word items that fall under these two categories always work with a noun of one kind or another. They tend to function as determiners within the nominal group, as will be explained in Chapter 3.

Traditionally English has only two articles: definite article, the, and indefinite article, a. These words are often called determiners (which they are) but since there are many other kinds of words and groups that also function as determiners (e.g. demonstrative pronouns and indefinite pronouns), using the more traditional label of article seems more appropriate for this presentation. Inherent in the meanings associated to the and a is the notion of number (singular or plural) and definiteness (definite or indefinite). The differences between these two words could suggest that they should belong to different lexical classes. The, for example, is used with both singular and plural nouns but it always indicates that the object being referred to is already known or that it is a particular object (i.e. definite). For example, in the email text given earlier in this chapter, the speaker said: John has taken Tom to the dentist for a check-up. With the use of the, it is clear that it is a particular dentist, whereas if a had been used (John has taken Tom to a dentist for a check-up), then no particular dentist would be being referred to. The indefinite article a is always used with a singular countable noun (e.g. a dog but not *a sand) and it is used with the noun to indicate an indefinite (or non-specific) referent. Historically, it derived from the word one (the indefinite article was originally an) most probably due to influence from Norman French since Old English – like modern Welsh, for example – did not have an indefinite article. It is this quantity specification (i.e. one or single) that separates a from the and makes it reasonable to include it with the numerals.

The class of numerals includes words which express specific quantities (i.e. numbers). They are commonly listed within the adjective word class since they typically describe or modify nouns in terms of quantity. Numerals can also be considered as determiners of quantity since they specify the quantity (e.g. one dog, two dogs, five dogs). There are many other kinds of words which are used to express quantity (e.g. a cup of coffee, a bunch of bananas, a few trees), and in a functional sense numerals could be grouped with these words and groups (generally, nouns or adjectives and their groups).

2.3.1.8 Conjunctions

The class of conjunctions forms a relatively small set of words which serve to link or connect words, groups and clauses. They all work and behave in a very similar way. They always indicate a connection between two parts of language (e.g. to group together as with and, or to contrast or exclude as with or) as in the following examples.

· Conjoining words: I like [dogs] and [cats].

· Conjoining groups: I only read [historical novels] or [trashy magazines].

· Conjoining clauses: [I like John] but [he doesn’t like me].

As conjunctions, these words are fixed forms and, in general, they do not take any affixation (e.g. suffixes) as is possible with nouns, verbs, and adjectives and adverbs. However, new conjunctions can be formed by compounding two words, typically where one of the words is a conjunction (e.g. even if, on the grounds that). The most common examples of conjunctions are: and, or, but, so, if, because, since, although, while, unless.

2.3.1.9 Other lexical categories

It is impractical if not impossible to do justice to the topic of lexical classification in this book. There will always be words that do not fall neatly into these categories and some that may seem impossible to identify. I include in this section some of the ones that were not covered above, but if you are unsure about the nature of a particular word it is always good to consult an in-depth and comprehensive source (such as Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik, 1985).

Interjections and exclamations are really formulaic (or idiomatic) expressions that we have learned to slot in for certain contexts such as greetings or gratitude. They don’t work as words in the sense we have been discussing. They are fixed expressions. Examples of these include: hello, goodbye, what!, thanks and so on.

The English language, as with most languages, is full of such fixed expressions and idiomatic sayings. An expression such as ‘break a leg’, which has the meaning ‘good luck’, cannot be understood by knowing the meaning of each word. It is a fixed expression that is equivalent to a single word. No one would say ‘break your right leg’, and if they did they would actually mean for your right leg to get broken.

I have been using the word ‘word’ throughout this section because it is familiar, but most often when we think of what it means we think of an orthographic word which is marked in written language by spaces. It is a problematic term in linguistics because there are many examples where we find multi-word expressions such as ‘break a leg’ which really are single items. We also find some expressions are written as a single orthographic word and some as two or more. For example, ‘tea towel’ is written as two orthographic words whereas ‘cupboard’ is written as one, but each constitutes a single noun. So to avoid any ambiguity, the term ‘lexical item’ is preferred since it does not imply any particular number of orthographic words and lets us talk about a particular lexical item without concern for its orthographic representation (i.e. whether written as one single orthographic word or as two or more).

Many of the multi-word lexical items in the English language will be difficult to classify. For example, ‘kick the bucket’ would be difficult to classify as a verb even though it expresses an event. Sometimes these formulaic expressions are not fixed word for word as is the case for ‘kick the bucket’. If the bucket were to be replaced with anything else, the idiomatic meaning would be lost (e.g. He kicked the stove). In a saying such as ‘drop your guard’, which means to stop being cautious, the expression is considered semi-fixed because the verb can change (e.g. ‘lower’ or ‘relax’) and the reference of the pronoun (you) can vary (e.g. my, his). Identifying such expressions is difficult because it implies that the expression works at the level of the word rather than at the level of the group; in other words, the question is whether the multi-word expression has been built up through the grammar (compositional) or whether it is a single lexical item (non-compositional). Resolving this is beyond the scope of this textbook but it is a fascinating area of study. When analysing language, if in doubt, it is probably safest to analyse the expression as compositional and work out the group structure rather than assuming a formulaic expression without evidence to support it.

The overview of lexical classification presented in this section has been necessarily brief and selective. See Section 2.7 for suggestions for further reading on this topic.

2.3.2 Groups and group classification

In a book about grammar, even functional grammar, space is not often given to words and word classes. A brief overview, such as the one given in the previous section, is necessary because our understanding of grammatical structure is largely based on lexical categorization. There is also an underlying premise that these items behave sufficiently similarly that the units of structure which develop from the items (usually through modification) can be described in more or less fixed or regular terms. Consequently, for most of the lexical classes discussed above, there is a corresponding group structure associated to it. This section will briefly present the basic concept of the group as a structural unit and the general considerations that are needed to describe and represent group structure. Specific groups will be discussed throughout the next few chapters, where they will be introduced as required.

Written language has imposed upon us the notion of unit. We generally recognize word, sentence, paragraph, and perhaps text as units of language. Language description must be broader than a specific kind of language use (e.g. written language). In linguistics we tend to think of language units in terms of levels or ranks either from smallest to largest units or vice versa. If we ignore sound units (phonemes), the smallest unit is the morpheme, which is generally accepted as the smallest unit of meaning. A morpheme can correspond to a single word, as in dog, or combine within a single word, as in dogs (dog + plural, ‘s’). The highest grammatical structure we can recognize (at least in terms of a generic structure) is the clause. However, between these two levels, there are intermediate units where words are grouped together. As Halliday explains (1994: 180), ‘describing a sentence as a construction of words is rather like describing a house as a construction of bricks, without recognizing the walls and the rooms as intermediate structural units’.

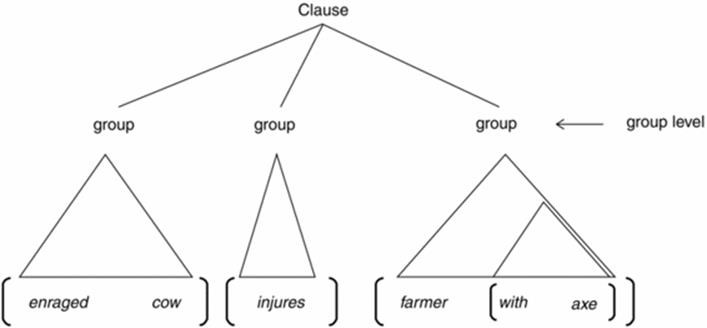

This can be illustrated with the following humorous example from a newspaper headline, which for one reading at least suggests a highly dexterous cow that is able to wield an axe.

(19) Enraged cow injures farmer with axe

If we were to ignore the internal boundaries marking the intermediate structural units between the word and clause levels, we would probably struggle to make sense of this clause. The structural ambiguity presented here is identical to the Groucho Marx example, I shot an elephant in my pyjamas, which was discussed in Chapter 1. If, as illustrated in examples (20) and (21), the structural boundaries (shown by enclosed boxes) within the clause are interpreted differently, we get a completely different meaning.In (20), the cow used an axe to injure the farmer but in (21) the farmer had an axe with him when the cow injured him. Speakers recognize these group structures without really being aware of them, and the humour in examples such as this one and the Groucho Marx joke is proof of this. They show that there is a level at which a set of grouped words act like a single unit. The intended meaning, as given in (21), is illustrated in Figure 2.7.

(20) Enraged cow injures farmer with axe

(21) Enraged cow injures farmer with axe

Figure 2.7 Level of group structure

All recognizable units have an internal structure that can be described (although these descriptions are often the subject of theoretical debate). The notion of structure implies that it is something that has some kind of framework and boundaries (as for a house, for example). There is a difference to be made between the generic structure of a particular group and the structure realized in a particular clause. In the former, the generic structure is a generalized description of a particular group which represents the full potential of the group (i.e. it includes everything that is possible). In the latter, the description of a particular clause will only include a representation of the structures that were actually expressed in this particular instance. As we will see for example in Chapter 3, the description of the nominal group will present the full range of possibilities for this group.

2.3.2.1 Classification of groups

There are two main types of structural unit which are generally used in the literature on grammar: phrase and group. The distinction between these two terms is somewhat contentious and, without entering into this theoretical debate, I would like to make clear how they are being interpreted in this book.

For many these two terms refer to the same thing; that is, a grammatical unit which is seen as operating at a level between the word and the clause. However, for Halliday there is a distinction to be made and he claims that a group is an expansion of a word whereas a phrase is a contraction of a clause. Amongst the various structural units that have been identified, some do seem to be structured based on a particular word class which can be modified or expanded. Others do not and yet they maintain a regular structural pattern as a unit. Following Halliday, a distinction will be made between units which work more as a group and those which operate more as a phrase. However, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to use either phrase or group as a more general heading for these units without specifying any distinctions.

Groups are units which are based on a head element which may be modified by other elements; the head element is the only required element of a group, with all other elements being optional. This is a relatively standard or common head + modifier type of structure, where the head is based on a particular word class (e.g. noun or verb) and the way in which the head can expand, through modification, to form a group is captured by the full generic description of the particular group. In this book, the main groups included for the English language are: nominal group, verb group, adjective/adverb group and quantity group. Each group will be presented and described in detail in the appropriate places throughout the book. For example, the whole of Chapter 3 is devoted to the nominal group, including other related groups and phrase units (e.g. adjective group and prepositional phrase) as needed, and the verb group is presented in Chapter 5.

Phrases are those units which are based on a pivotal element which must be completed by one or more elements. This is in contrast to the head + modifier relationship found in groups; even though the head element of a group is a kind of pivotal element, there is no requirement for a modifier to be expressed. With a phrase, it is the combination of the pivotal element and the completing element(s) that define the phrase. In other words, one is not seen as a modification of the other but rather as a completion or Complement. Therefore, in a phrase, at least two elements are required: the pivotal element and the completing element(s). Examples of phrases include: clause, prepositional phrase and genitive phrase.

One central concept concerning the clause has been repeated throughout the book so far: the clause is multifunctional. Every clause serves several different functions at the same time; the structure of the clause is defined by the configuration of these functions. Furthermore, any individual constituent of the clause is also multifunctional in the sense that ‘in nearly all instances a constituent has more than one function at a time’ (Halliday, 1994: 30). Identifying the constituency and structure of the clause is made quite challenging because of its multifunctional nature. As Halliday (1994: 35) explains, ‘the clause is a composite entity. It is constituted not of one dimension of structure but of three, and each of the three construes a distinctive meaning.’ Each dimension has associated to it particular functional elements. As a result of the three dimensions (relating structure and meaning), the clause is best described in terms of the full set of functional elements. This is why the presentation of the clause is given in stages throughout the book.

2.4 An initial view of the clause: representing functions and structures

The clause has been described so far as a structural unit which expresses a given situation. In Chapter 1, the multifunctional nature of the clause was briefly presented, and the concept of metafunctions was introduced. The metafunctions each construe different and distinctive meanings, and each has its own structural configuration of elements. This means that the clause is a complex entity and one which has integrated the metafunctions simultaneously such that separating them and isolating them is an artificial exercise. However, this is, to a certain extent, what we must do in practice because analysis is relatively linear and it is generally done in steps. Different analysts will find it preferable to begin the analysis of the clause from different starting points. In this book, the preferred starting point is the clause as representation – the experiential metafunction, which involves identifying and describing the process and any participants involved. In this section, a very general view of this metafunction will be presented as a starting point, which will then lead into more detailed analysis in the following chapters. Specific detail about the analysis is given in Chapter 4.

We can rely on the basic principle of the clause, which is that it will have one and only one main verb. The main verb expresses the process, and so if we can identify the process and main verb it should be a good starting point for teasing out the rest of the analysis. As we saw earlier in this chapter, this can prove rather challenging when a clause has more than one verb. To make things simple for our current purposes, we will analyse a short text with relatively simple clauses; the This little piggy nursery rhyme, given below as Text 2.2.

Text 2.2 This little piggy

This little piggy went to market.

This little piggy stayed home.

This little piggy ate roast beef.

This little piggy had none.

And this little piggy went all the way home.

The first step in analysing text is to identify the clauses. Since the text above is written and includes punctuation, we can assume that each sentence has at least one clause. Therefore, each sentence becomes a potential clause and must be examined further before it can be determined that the clause boundaries have been correctly identified. In order to do this, all verbs in each potential clause must be identified, and if more than one verb is found then further investigation is required. A set of guidelines on how to do this is developed in Chapter 7. In this case, the text is a fairly simple text with only one verb in each sentence. We can therefore rely on each orthographic sentence in the text as one single clause.

The analysis of Text 2.2 will begin by listing all the clauses in the text and then working through the initial analysis in general terms using the process test (see below). Basic tree diagrams are provided to illustrate the analysis at this stage.

Here is the list of clauses, with the verbs underlined:

1. [1] This little piggy went to market

2. [2] This little piggy stayed home

3. [3] This little piggy ate roast beef

4. [4] This little piggy had none

5. [5] And this little piggy went all the way home

The main verb of each clause expresses the process, and it is the process which determines what participating entities are expected within the situation. The term participating entity or participant needs to be seen in the sense given in section 2.2 above and not in its common meaning of person. There is a test that can be used to help work out the participants. The process test (see Fawcett, 2008) relies on what speakers know about how a particular verb works to express a process. The test itself is a way of generalizing the particular situation|clause being analysed so that the number of participants involved can be determined, and so that the participants may be identified in the clause. The process test is given below and, to use it, simply replace the word ‘verb’ with the actual verb being tested and see which participant(s) are naturally expected to complete the process. The process test implies that every situation|clause will have one process and at least one participant. It is sometimes difficult to know whether or not there is a second participant, and this will be discussed in Chapter 4. The second and third participants are represented in parentheses in the test since different verbs have different configurations of participants, and not all of those listed will need to be used. Every verb has at least one Participant but some have two or even three. I cannot think of any example of a process with four or more participants. The process test is written to accommodate these configurations in very general terms.

Process test

In a process of [verb-]ing, we expect to find someone/something [verb-]ing (someone/something) ((to/from) someone/something or somewhere).