Analysing English Grammar: A Systemic Functional Introduction (2012)

Chapter 3: The grammar of things: the nominal group

As speakers, the first grammar we learn is most often the grammar of things. The vocabulary of young English speaking children typically will include nominal expressions such as ball, mamma, dadda, cat, dog, juice, water, and so on. There is considerable variation of course but these word forms are used to communicate; that is, to ask for things or to tell someone something. They provide a basis upon which to build up the grammar of the language. The grammar of things is precisely what this chapter will describe.

As was shown in the previous chapter, many of the main word classes form the basis of the main structural units of the clause. The most important of these is the unit of the group, which is considered as an extension of the word. Chapter 2 also introduced some terminology and notation that will be helpful for the exploration into analysing English grammar presented in this book.

This chapter is the first detailed look at one particular part of the grammar. It begins with an introduction to referring expressions and then moves on in section 3.2 to describe the nominal group, which is the main linguistic resource for these expressions. The nominal group is a complex unit which expresses a range of meanings. Once this description is complete, some guidelines are presented in section 3.3 which offer help in recognizing nominal group boundaries. As a summary, 3.4 provides a worked example of nominal group analysis.

3.1 Introduction to referring expressions

You might be wondering why the nominal group is being given prominence in this book. After all, it is the subject of our first detailed look at analysing language. It is being presented before any details about the clause or any other unit of language. This reflects the belief I have that, in the English language at least, entities (i.e. things, people, objects, ideas and concepts) are more relevant and salient than anything else. When we use language, we generally want to say something about something or someone. If we group all the kinds of things we can say something about into one category, it will make it much easier to say something about these things. So we will use the term entity to refer to anything that we can say something about and the term will include things, objects, persons, living things, abstract things, concepts, and so on.

As discussed in Chapter 2, when a speaker says something about one or more entities, they are describing (very loosely) a situation, and this situation is represented in language by the clause. Once included in the situation, we will refer to the entity or entities as participating entities or participants because they participate in the situation in some way. In the next chapter we will take a close look at the various ways in which participating entities can function within the situation. Before moving on to an example, it may be useful at this point to clarify some of the terminology that is used in this chapter.

Entity:

a term used to categorize a distinct thing in the speaker’s world, including living things, non-living things, places, concepts, ideas, phenomena, etc. (e.g. dog, chair, woman, climate, unicorn, president, wind, ghost, love, happiness, sand, feeling, emotion, puddle. . .)

Referent:

something outside the language system (i.e. non-linguistic entity) that the speaker wants to refer to; in other words, something that is brought into focus or attention by the speaker. It is a concept in the mind of the speaker rather than an object in the world (e.g. in I like my neighbour’s new car, the speaker has a mental image or concept of what he or she wants to refer to).

Refer:

a process created by a speaker who uses a linguistic expression to indicate or identify a referent for the addressee.

Participating entity (participant):

an entity which is included (participating) as a referent in a situation and is therefore completing a process.

Referring expression:

the linguistic representation of a referent (i.e. a linguistic expression used by a speaker to refer to a referent). This is most commonly expressed as a nominal group.

To illustrate what these terms mean and how they are used, consider Text 3.1 below. It is a short excerpt from an interview1 with Rick Falkvinge, who is a strong advocate of the legalization of file sharing. In this brief text we will focus on one particular referent:

Text 3.1 Excerpt from an interview with Rick Falkvinge

A mass surveillance proposal for wiretapping every communication crossing the country’s border was introduced in 2005, then [it was] retracted because it had received too much attention. It was reintroduced by the new administration and [it] is pending a new vote this summer.

For now we will ignore the complexity of the first referring expression other than to say that it is a very detailed and descriptive expression. The speaker could have simply said either a surveillance proposal was introduced in 2005 or a proposal was introduced in 2005. The referent of these expressions is significant in this excerpt and it is clearly an important feature since it is repeated five times in this short text. In each case, the referent is a participating entity because the speaker has included it in specific situations. These situations include processes of introducing, retracting, receiving, reintroducing and pending. The entity (i.e. the referent) is participating in each of these processes and consequently each instance constitutes a participating entity. The specific function of each participating entity will differ in relation to different processes and this will be discussed in Chapter 4.

As stated above, then, we can define a referring expression as a linguistic expression that the speaker uses to refer to an entity which is a participant in the situation he or she is describing. The organization of these expressions is not random; there is a pattern or a grammar to them. Languages have resources to govern this organization. The most common or frequent linguistic resource in English for doing this is the nominal group. The nominal group gives linguistic structure to this part of the language – the part that lets speakers refer to the entities they want to say something about.

Consider a simple sentence such as My neighbour is nice. The referent is the person who lives next door to the speaker and the referring expression is a nominal group (neighbour is a noun and my neighbour is a nominal group). This type of sentence can be used generally to help us recognize these referring expressions. Any referring expression should be able to fit into the X slot in the generic sentence: X is/are Y, provided that Y is giving us some information about X (i.e. a description). In the invented examples from (1) to (7), the expression in the X slot is underlined.It is clear from this list of examples that some expressions are longer than others. In fact, there is no theoretical limit to the length of a referring expression as we will see later in this chapter. However, they all have some things in common and this relates to how the words combine to function as a group. The trick is to be able to recognize when a series of words is working together as a group to serve some function in the clause or in another group and to be able to identify where the boundaries of this group are. If a referring expression is a linguistic expression which is used by a speaker to refer to some referent, then it will have a function; in other words it will be doing something for the speaker. We will come to a better understanding of the various functions it can have in later chapters. For the moment we will concentrate on how to recognize these types of expressions by considering the structure of the nominal group. The way in which words group together to form a referring expression is regular enough that we can talk about it generically. In the next section we will take a detailed look at the nominal group.

(1) A man is an adult human male

(2) The house is beautiful

(3) Those two apples are organic

(4) Unicorns are real

(5) Love is free

(6) The man in the moon is scary

(7) The leather bag that I saw in Marks and Spencer is expensive

3.2 The nominal group

So far the nominal group has only been mentioned in passing. All that has been said up until now is that it is the main linguistic resource speakers have for referring to a referent. By linguistic resource I mean that it is a group of words which is organized by the language system. This idea of organization is important since the language system doesn’t often allow any random arrangement of words; the grouping of words fits a particular pattern. What we want to do now is describe this pattern; in other words, we want to describe the way in which words can group together to enable a speaker to refer to a referent. In Text 3.1, the most frequent referring expression used to refer to the referent (

The first referring expression in Text 3.1 is a complex nominal group which clearly has more than one element: A mass surveillance proposal for wiretapping every communication crossing the country’s border. The length of this nominal group shows how important it is to be aware of group boundaries and to know how to identify where a group begins and ends. The expression gives us quite a bit of information: the entity being referred to is a proposal(it isn’t something else like a letter or a book); there is only one proposal involved (rather than more than one or an unspecified number of proposals); the expression describes what kind of proposal is being referred to (mass surveillance); and it describes the proposal in terms of what it will be used for (for wiretapping every communication crossing the country’s border). In very general terms, there are four different kinds of information included in the referring expression and, as will be shown below, these correspond to particular elements of the nominal group.

In this section, we will describe the potential of the nominal group – in other words, its generic structure. To do so we will consider the range of possible functional elements. It should be said here that coverage of the full range of the potential of the nominal group would be beyond the limits of this book. The goal here is to present a thorough but basic approach to analysing language. Once the concepts, functions and structures presented here are mastered, further exploration in more detailed literature will help complete the full picture.

As part of our language system, we know what resources we have available to enable us to talk about things or objects. Children work this out very early in their language development. My son, at age two years ten months, had no trouble saying things like that’s the same book we saw at the shop yesterday, which is a very complex way to refer to a particular book. A speaker just somehow knows how to construct an expression that will enable an addressee to identify what it is that he or she is referring to. As effortless as it may seem to do this, it can be quite challenging for the analyst to sort out the ways in which language is grouped and how it functions.

There is a very strong relationship between referring expressions and the structure of the nominal group. This isn’t really surprising because referring expressions are used to refer to a referent. Something most of us were taught from a very early age is that a noun is a person, place or thing, which is a very restricted view. Nouns are the words used in the language system to represent (or denote) entities in the non-linguistic world (i.e. things that are real or imaginary, whether living or not including concepts). In other words, nouns are the way we classify the things we want to talk about (e.g. ‘cat’ classifies all entities that we consider similar enough to belong to this class). Derived nouns (nominalizations), such as evaluation, work in the same way except that the noun is classifying the process behind the derived noun (i.e. as represented by the root verb) as a kind of entity. For example, evaluationdenotes the process of evaluating or the result of evaluating and, as a process or a result, evaluation is a kind of entity. This is true for all nominalizations regardless of whether the verbal qualities are transparent or not (e.g. cancellation may immediately evoke the verb cancel but revolution is not transparent and does not suggest the verb revolve, although it is debatable whether or not such borrowed items should be considered nominalizations).

As discussed in Chapter 2, groups are formed by the patterns of structures which support the expansion of a particular word class. Therefore the nominal group can be thought of as the structure of the words that group around a noun. We need to ask two important questions in order to understand the nominal group: What is the context of nouns? How do they function? We will focus on the first of these two questions in this chapter. The functions that the nominal group realizes in the clause will be explored in Chapter 4 when we consider the clause in more detail. As a summary of the main features of nouns (which were presented in Chapter 2):

· Nouns can be determined either by number or amount or by whether the referent is already assumed to be known to the addressee:

o

§ one cat vs. five cats, or the sand vs. some sand

§ the cat vs. a cat

o Words which have this kind of determining function in relation to nouns are called determiners. The most common word classes associated to this function are articles, demonstratives and numeratives.

· Nouns can be modified in order to give more descriptive or identifying detail to the referring expression:

o

§ nice cat, bad cat, fat cats, the cat with stripes

o This is different from the determining functions of the nominal group. The modifier function describes the entity (noun). As we will see below, there are two ways nouns can be modified. One is in the position immediately before the noun; a pre-modifier. The other is immediately following the noun; a post-modifier. The most common word class associated to the function of pre-modifier is the adjective class (nice, bad, etc.).

These generalizations about how nouns work can be used to test whether or not a given word is indeed a noun in a particular context or whether it is something else (for example a verb or an adjective). This is relevant for recognizing nominal groups and their boundaries given the principle of group structure.

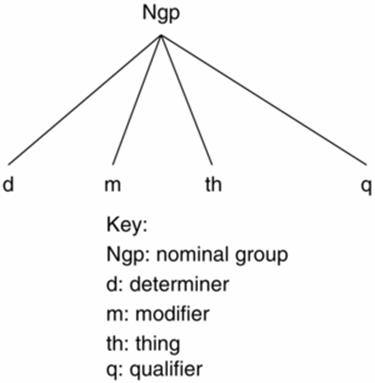

The description of the nominal group (Ngp) presented here is adapted from Fawcett (2000c), which offers a very detailed account of this structure. The nominal group has four main types of element: determiners (d), modifier (m), thing (th), and qualifier (q). Each of these will be presented in detail in the sections below. The most basic structure of the Ngp can be described by the following elements: {determiner + modifier + thing + qualifier}.

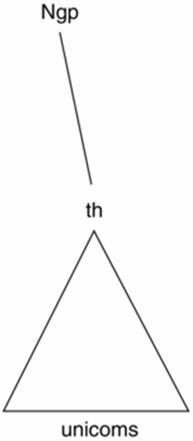

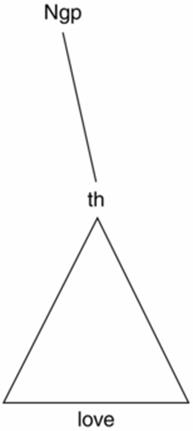

Not all elements in the nominal group are obligatory. In fact, as we saw in the examples above, some nominal groups have only one element (e.g. unicorns). The thing element is the only element which must be present in the nominal group. It is an essential element because its role is either to denote the entity being referred to or to refer directly to the referent by reference (i.e. the use of a pronoun such as she). There are instances, as we will see later, where the thing element is not actually expressed and is left empty (ellipsis), but in these cases it can easily be recovered. We will leave this exception for the moment. If the thing element is the only obligatory element then all other elements are optional. Furthermore, there can only be one thing element but it is possible to have more than one determiner, modifier or qualifier. This can be expressed using notation, where an asterisk, *, after the element means ‘can be repeated’ and the parentheses mean the element is optional, as follows: {(d)* (m)* th (q)*}.

This states that the nominal group must include the thing element and it may optionally include a determiner and/or modifier and/or qualifier. It also states that there can be more than one determiner, modifier and/or qualifier.

Each element represents a function within the expression. If, as we stated above, the expression is being used to refer to some entity, then we should expect to find a representation of that entity within the expression. Above, it was pointed out that in English we tend to use nouns for this purpose. Nouns are words that are used to denote an entity (e.g. car, flour, house, love, kindness). If I want to refer to a particular house, I may use the noun house to denote what kind of entity I am talking about. In addition to this, I may want to further classify the referent by the expression the red house. In doing so, I sub-classify the referent in the sense that the expression excludes all non-house and all non-red entities. The main function within the nominal group then is the thing element, which is the linguistic classification or representation of the entity being referred to. Frequently, this is the only element of a nominal group. In examples (1) to (7) above, there are two such instances: unicorns and love. In each nominal group, there is only one element and it is the thing element. However, as shown in the remaining examples, the nominal group may contain other elements (e.g. the man in the moon) and, for each example given, the other elements can be described in terms of the four main types of elements introduced above.

This section will explain the basic structures with a few examples of each nominal group element and then move on to analysing full nominal groups. The generic organization of the nominal group is given in Figure 3.1, which shows the order in which the elements occur: determiners occur before modifiers, modifiers occur before the thing, and qualifiers always occur after the thing.

Figure 3.1 The basic organization of the nominal group

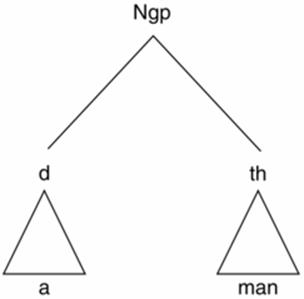

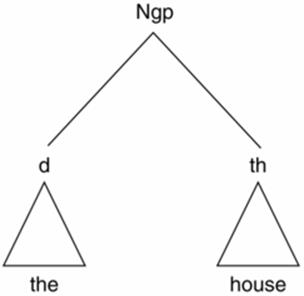

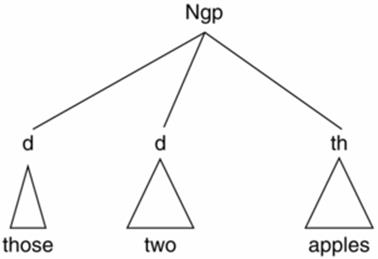

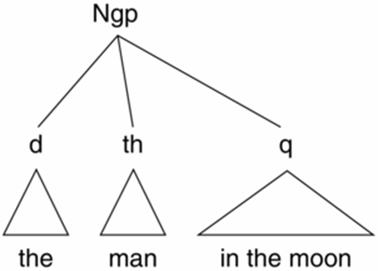

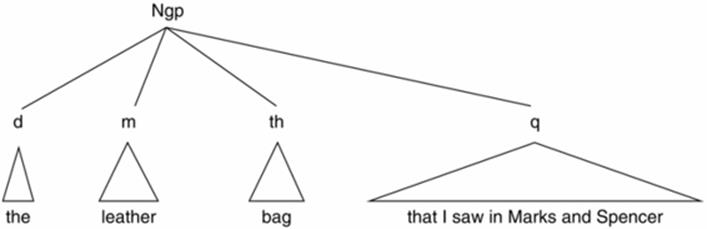

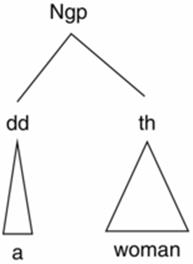

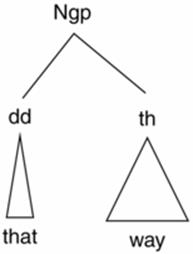

The nominal groups from examples (1) to (7) above have been represented as tree diagrams in Figures 3.2 to 3.8. Figures 3.2 and 3.3 show examples of a nominal group with thing as the single element. Figures 3.4 and 3.5each show an example of a nominal group with a determiner + thing. Figure 3.6 illustrates two determiners preceding the thing element. In the section below on determiners we will come back to this type of example because there is much more to say about these determiners. Each of the two determiners has a different type of determining function. In Figure 3.7 the nominal group structure is that of determiner + thing + qualifier. Here in the moon is describing man. Qualifiers are interesting because this type of description involves another referring expression, and you might have noticed the moon as another nominal group within the nominal group the man in the moon. This will be discussed in detail in the section on qualifiers. Finally in Figure 3.8 we see an example of a nominal group with all four main elements represented.

Figure 3.2 Example 4, unicorns

Figure 3.3 Example 5, love

Figure 3.4 Example 1, a man

Figure 3.5 Example 2, the house

Figure 3.6 Example 3, those two apples

Figure 3.7 Example 6, the man in the moon

Figure 3.8 Example 7, the leather bag that I saw in Marks and Spencer

The remainder of this section presents a description of the main elements of the nominal group.

3.2.1 Determiners

There are many types of determiner but all of them have a similar function. The following three types of determiner will be discussed in this section: deictic determiner (dd), partitive determiner (pd), and quantifying determiner (qd). The deictic determiner may be more familiar in some ways than the other two. As will be discussed below, the partitive determiner and the quantifying determiner sometimes require the addition of an extra element in the nominal group called the selector element, which is represented in notation by ‘v’ and which is always expressed by the preposition ‘of’. This element provides a structural link between the determiner and the head of the nominal group. The principle of selection does not always require the presence of the selector element (‘of’) and sometimes it is not expressed. If we consider the examples in (8) and (9), the thing element for both is apples. However in (8) the nominal group expresses a quantifying determiner and thing, whereas in (9) the quantity is being expressed as a selection from a set.There are some very tricky areas related to the selector, specifically concerning the use of ‘of’ in nominal groups. There are references in the section on further reading at the end of this chapter which would be of interest to those wanting more information about this construction. The selector element of the nominal group is particularly significant in instances of selection involving the quantifying determiner or the partitive determiner, and this will be discussed in the relevant sections below.

(8) five apples

(9) five of those apples

In the description of the nominal group given above, we saw that determiners were optional and that they could repeat. In other words, it is possible to have more than one. In fact, it is possible to have more than one determiner but it so happens that, in English at least, specific types of determiner don’t repeat. So while we may have a deictic determiner and a quantifying determiner (i.e. more than one determiner), we won’t have more than one deictic determiner or more than one quantifying determiner. This is an important distinction.

The order of occurrence of the determiner elements is more or less fixed, so we can now revise the basic structure of the nominal group from {(d)* (m)* th (q)*} to {(pd) (v) (qd) (v) (dd) (m)* th (q)*}.

However, these two statements are saying the same thing. One is simply more specific than the other.

3.2.1.1 Deictic determiners

The use of a deictic determiner (dd) includes an implicature of definiteness or uniqueness in the sense that they specify or identify the referent in some way. For example, if when shopping with a friend in a furniture store I say ‘this table is really nice’, then my friend will know exactly which table I am referring to, not by its description but by the way I identify it with respect to the context by the use of a deictic determiner. So this type of determiner has the function of making the referent a particular referent. The use of a deictic determiner in a nominal group implies that the speaker believes he or she can presume that the referent can be identified by the addressee. This category includes what have been called definite articles, demonstrative pronouns and possessive phrases (including possessive pronouns).

Examples of deictic determiners (dd)

a, the, this, that, those, these, my, his, their, John’s, my neighbour’s, my friend’s mother’s, the nice man’s

3.2.1.2 Genitive phrases

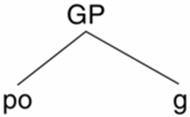

If you look closely at the examples of deictic determiners given above such as my neighbour’s or the nice man’s, you might notice that some look suspiciously like nominal groups themselves, and to a certain extent this is right. However, this kind of expression is not a group because it is not based on a lexical head word. There are two required elements in this structural unit: the entity involved (the possessor) and the marker of the possessive relations (the genitive marker). The name of this unit is the genitive phrase (GP). When a nominal group includes this type of phrase, it is always being used to express a determiner function. Within the genitive phrase, the two main elements are called the possessor (po) and the genitive element (g). In the possessive examples given above, some have a suffix, the genitive marker, which indicates who or what the possessor is. This isn’t always necessary, as is shown by the genitive pronouns (my, his, their, etc.). In these cases the genitive marker has been incorporated into the pronoun (compare: I, me, my for example). Both the possessor and the genitive marker are obligatory elements of this cluster. The function involved here is in relation to the thing and not to any other element within this cluster. When a genitive marker is present, it cannot really be seen as having a modifier function with respect to the possessor element or vice versa. It is rather a structural (inflectional) marker. Figure 3.9 shows the basic structure of the genitive cluster and its relationship to the deictic determiner in the nominal group. An example of this is shown in Figure 3.10. When the deictic determiner is realized by a possessive pronoun, then the relationship between the linguistic form and the function can be simply noted as in Figure 3.11, which shows the deictic determiner as directly expressed by the item his. The use of the possessive pronoun in this case is very similar to the definite article.

Figure 3.9 The generic structure of the genitive phrase

Figure 3.10 Genitive phrase expressing the function of deictic determiner

Figure 3.11 Deictic determiner directly expressed by a possessive pronoun

3.2.1.3 Quantifying determiners

The function of the quantifying determiner (qd) is to indicate the quantity or amount of the thing being referred to (Fawcett, 2000c). The quantity may be very specific, as in three sandwiches, or non-specific, as in some sandwiches. We can recognize a quantifying determiner because it will answer the question ‘how much?’ or ‘how many?’.

Examples of quantifying determiners (qd)

a, some, many, one, two, six hundred, almost fifty, very few, about seven, two cups, a handful, a pinch

As with the deictic determiner (e.g. the, this, my, John’s), which is most frequently realized by the, sometimes the quantifying determiner (e.g. two, some, a teaspoon) is expressed by a single item such as five and sometimes it is realized by a group such as a nominal group (e.g. two cups of coffee) or a quantity group (e.g. nearly five people). The article ‘a’ is included among the quantifying determiners as well as in the set of examples above for deictic determiners because it has both the function of a determiner and the function of specifying an amount. Unlike the, which can be followed by a quantity (e.g. the five men), ‘a’ takes up both functions and there cannot be both a deictic determiner and quantifying determiner (e.g. a man but *a two men and *the a man). Note that examples such as a couple (of) people is not an instance of deictic determiner plus quantifying determiner preceding the thing element but rather only quantifying determiner, since a couple expresses the quantity (in this case the quantifying determiner is expressed by the nominal group a couple).

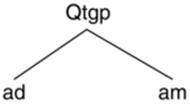

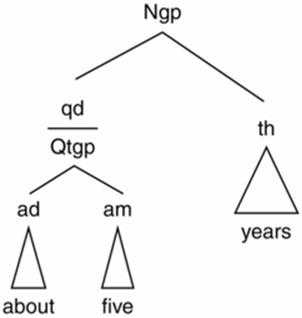

The quantity group (Qtgp) organizes the structure of quantities and amounts (see Fawcett, 2000c). The main element of this group is called amount (am). In addition to this, it is also possible to have an adjustor (ad) element. The basic structure of this group is given in Figure 3.12. Whether a quantifying determiner is expressed as a nominal group or a quantity group is determined by what type of lexical item is conveying the amount. If it is a noun, as in a cup, then it will be expressed by a nominal group. If it is numerative, such as five, then it will be expressed by a quantity group. The distinction is based on the lexical class of the head element of the group – that is, whether it is a thing element (a nominal group) or an amount element (a quantity group).

Figure 3.12 The structure of the quantity group

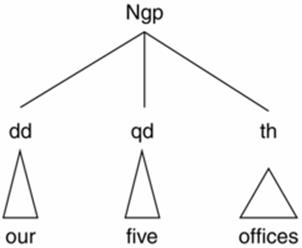

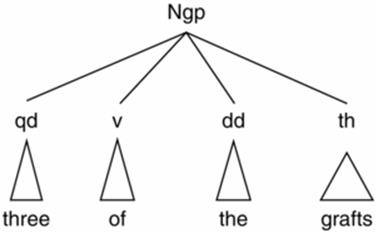

Examples (10) to (12) illustrate the various ways in which the quantifying determiner is realized. The tree diagram for each underlined nominal group is shown in Figures 3.13 to 15.

(10) We are relocating our five offices

(11) The blood is going through three of the grafts

(12) I hadn’t seen him in about three years

Figure 3.13 Example 10, our five offices

Figure 3.14 Example 11, three of the grafts

Figure 3.15 Example 12, about five years

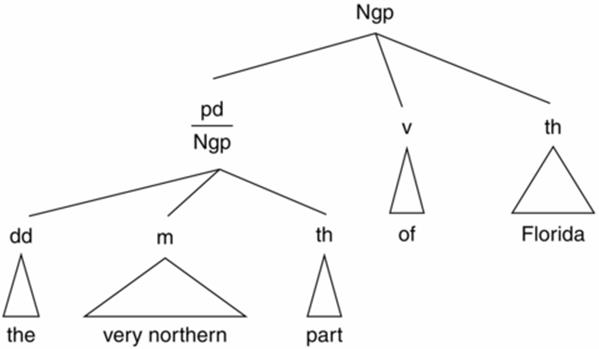

3.2.2 Partitive determiners

The partitive determiner (pd) is much less frequent than deictic determiners and quantifying determiners. Its function is to indicate that the referent is a part of the entity being referred to (Fawcett, 2000c), such as in I’m painting the top of the desk (cf. I’m painting the desk top). Clearly in this example what is being painted is the desk. Therefore the thing being referred to has been classified as desk. Partitive determiners always require the selector element (v) (note the use of ‘of’ in the examples in the box).

Examples of partitive determiners (pd)

the top (the top of the desk), the back (the back of the house), a part (a part of the book), the arm (the arm of the chair), a section (a section of the room)

The examples given above are all nominal groups. This is the only realization for the partitive determiner. Therefore there is no particular group associated to the partitive determiner as there is for the quantifying determiner and the deictic determiner.

The implication here is that being able to identify the thing element is critical to the analysis of the nominal group. Consider examples (13) to (15) given below, where the nominal groups of interest have been underlined. If we were to select the first noun in each case, we would be forced to see it as the thing element. This would mean that the classification of the entity being referred to would be part, area and rest respectively. The consequence of this is that it forces the analyst to treat the remainder of the nominal group as a qualifier (i.e. as a post-modifier of the thing element). Of course we can’t be certain of the speaker’s real intentions, but from the analytical perspective it seems more reasonable to consider Florida, mill and mill as the entities being referred to. This lets us recognize the determiner function of the very northern part, an area and the rest. The tree diagram for example (13) is given in Figure 3.16 to illustrate the associated structure for the partitive determiner in this example.

(13) she is in the very northern part of Florida

(14) the green end is an area of the mill

(15) the remaining three supervisors had responsibility for the rest of the mill

Figure 3.16 The partitive determiner as expressed by a nominal group

We’ll discuss the role of the thing element again in the section below on qualifiers. For now, let’s just accept that the key to understanding the nominal group is through the identification of the thing element (which represents the entity being referred to) and working through the functions of the remaining elements to find a ‘best fit’ analysis.

3.2.3 Modifiers

There is a distinction to be made between determiners on the one hand and modifiers (m) and qualifiers (q) on the other hand. In very general terms, determiners signal the referent by the specification of the entity (i.e. definiteness, quantity and/or possession). Modifiers and qualifiers function differently since they are more like descriptions. They typically contribute to the classification of the thing. For example, red in a red car does not express a meaning which could identify specifically the entity being referred to but it does describe it in such a way that it says something that further specifies or sub-classifies the car. As with all other elements, there are many things to consider in analysing modifiers and qualifiers. The discussion of these two elements will be kept as simple as possible, but for those wanting more detail the section on further reading at the end of this chapter lists relevant literature on these topics.

There are two main functions of modifiers within the nominal group: classification and description. A classification modifier (cf. Classifier, Halliday, 1994) has the function of classifying the referent as being a member of a sub-set of the class to which the entity belongs (e.g. the bus station, where bus sub-classifies station). A description modifier (cf. Epithet, Halliday, 1994) functions to describe the entity with more descriptive detail (e.g. a cool breeze). As was stated above, modifiers always occur immediately preceding the thing element, although generally classifying modifiers occur immediately before the thing element after any describing modifiers.

Examples of modifiers (m)

red, wooden, sharp, wet, kind, ugly, beautiful, leather, brick, colourful, very smart, really black, extraordinarily intelligent, easy

The examples of modifiers given in the box show a pattern in the type of word or words that realize this type of meaning. Some words should look familiar since they are nouns (e.g. leather, brick). You might recognize now that this means that modifiers can be expressed by nominal groups. Most of the other words in the list are adjectives. Adjectives are the most common form of modifier. What might also be clear now is that some adjectives have words grouped with them and these are examples of the adjective group. This is indeed what we find, except that there is a kind of duplication since this type of group works in the same way for both adjectives and adverbs. Some academics combine these groups into one and others only consider the adverb group. We won’t consider the case of adverb groups now since they are not directly relevant to the nominal group and they will be discussed in Chapter 4. However, we will take a look at the elements of the adjective group now and consider how it works within the nominal group.

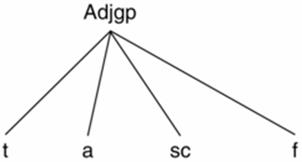

3.2.3.1 The adjective group

The adjective group (Adjgp), as with all groups, has a particular class of lexical item as its head; in this case it is the adjective. The description of this group is based on work done by Tucker (1998) and his terminology for the elements of this group has been adopted. The head element of the adjective group is called the apex (a). It is always expressed as an adjective (in the case of the adverb group, the apex is expressed as an adverb – see Chapter 4).

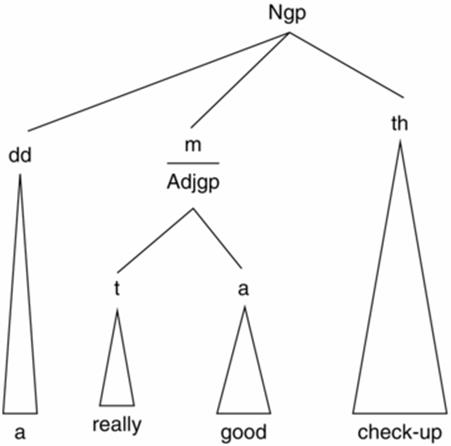

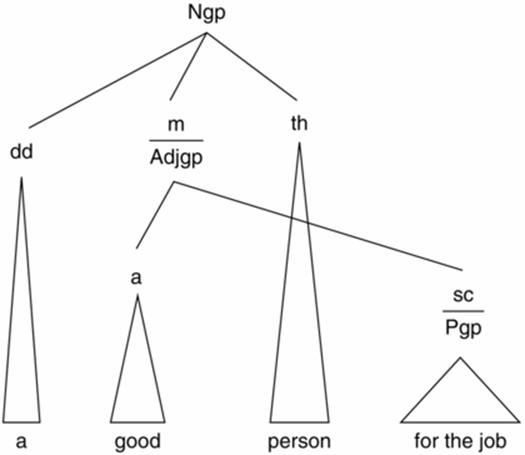

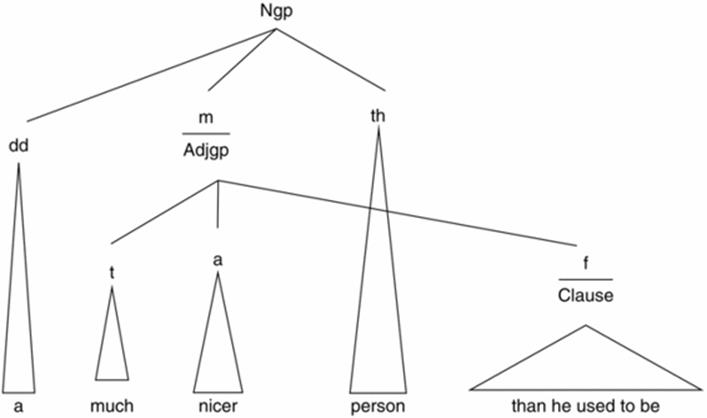

The basic organization of the adjective group is illustrated in Figure 3.17. The main element as stated above is the apex (a), and it is the only obligatory element. However, as with all groups, it is possible to modify the head. In the case of adjectives, such modification typically serves to temper the degree to which the adjective applies. So for example the quality of happy can be intensified or reduced as in very happy or somewhat happy. Therefore there is a need for an element within the adjective group for this function. This element is called a temperer (t). There are two other elements in the adjective group. These are scope (sc) and finisher (f); both are post-modifiers. The scope element has the function of post-modifying the head of the adjective group, for example, I am happy to see you, where the scope element is underscored. The finisher element is also a post-modifier but, unlike scope, it is an obligatory element which depends on the lexicogrammatical requirements of the head element (apex). Its function is to complete (or finish) the lexicogrammatical requirements of the comparative structure determined by the apex. The organization of all four elements is shown in Figure 3.17, with examples of specific instances following in Figures 3.18 to 3.20.

Figure 3.17 Basic structure of the adjective group

Figure 3.18 An adjective group expressing a modifier in a nominal group

Figure 3.19 Example of discontinuous scope within the adjective group

Figure 3.20 Finisher element separated from apex in adjective group

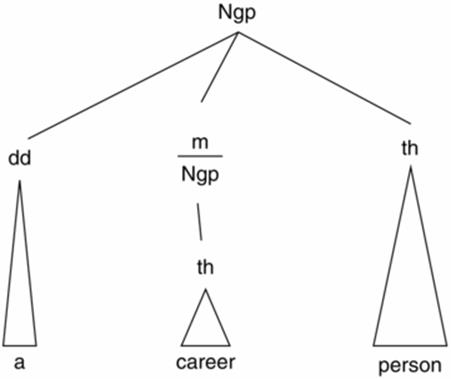

Perhaps the most common adjective group is of the type shown in example (16) and illustrated in Figure 3.18, where the adjective group is composed of the apex element and a temperer element (really good).When an adjective group expresses a modifier in a nominal group and it has a scope (sc) and/or a finisher (f), then these two elements will generally be separated from the apex by the thing element of the nominal group. This is shown in invented examples (17) and (18) (accompanied by Figures 3.19 and 3.20 respectively). In both cases the group of words after the thing element in the nominal group contributes meaning to the meaning of the apex rather than the thing element. For example for the job functions as scope because it limits or specifies the range of coverage of the adjective, good; in other words, she is not being said to be a ‘good’ person generally, but rather a person who is good for the job. In example (18), the finisher, than he used to be, is an obligatory element which completes the conditions of the comparative structure set up by the apex, nicer. It is not a qualifier element of the nominal group.To end this brief presentation of modifiers, consider the invented example given below in (19), which is illustrated in Figure 3.21. It illustrates the representation of cases where a nominal group, rather than an adjective group, realizes the modifier element in a nominal group.

(16) she had a really good check-up

(17) She is a good person for the job

(18) He is a much nicer person than he used to be

(19) She is a career person

Figure 3.21 Modifier realized by a nominal group

3.2.4 Qualifiers

The last element of the nominal group that we will consider is the qualifier element (q). It is similar in function to the modifier element in the sense that it adds to the overall description of the referent. There are two main structural differences between modifiers and qualifiers. The first is that modifiers occur before the thing element and qualifiers occur after it. The second is that, while modifiers are typically realized by an adjective group or a nominal group, qualifiers are most often expressed by prepositional phrases or clauses. It is possible for a qualifier to be expressed by a nominal group or an adjective group but this is relatively uncommon. The examples given below illustrate the four types of structure which express this function in English.

Examples of qualifiers (q)

Sue (as in my best friend Sue), in the corner (as in the table in the corner), that lives across the street (as in the dog that lives across the street), special (as in nothing special)

The functional differences between modifiers and qualifiers are less obvious. The qualifier extends the nominal group in a way that isn’t possible with the other elements. From the perspective of referring, the qualifier introduces another referring expression. In this sense, referring expressions which are realized by a nominal group having a qualifier are complex referring expressions since they always involve an additional (secondary) situation which is different from the one in which the entity is currently involved. This may be a difficult concept to comprehend without some examples. Example (20) should help clarify this.In (20), the nominal group of interest has been underlined. Whenever a nominal group is being analysed, the first task is to identify the thing element (which is the head of the group). In this case, the thing element is guys. How do we know this? The thing element must be a noun or a pronoun and in this example there are only three possibilities: one, guys and him. If we try to establish what entity the speaker is referring to (sometimes it helps to try to visualize this), then it should become clear from the context. In this case, one particular male person is the referent that the speaker has in mind. We can then be confident that guys is expressing the thing element and is therefore in the head position of the nominal group. Once this has been determined, it is relatively easy to sort out the remaining elements. This nominal group also expresses a quantity (one), the selector element (of) and a deictic determiner (the).

(20) He was one of the guys that found him

In this nominal group, up to and including the thing element, we find: qd + v + dd + thing. The rest of the nominal group, following the thing element, tells us which guy (or guys) is being referred to. In a sense the qualifier gives us more information, detail and description about the entity being referred to. The entity is involved in the main situation (i.e. in a process of being, he was one of the guys) and it is also involved, through the qualifier, in a secondary situation (i.e. in a process of finding, [the guys] found him). This secondary situation is created by the speaker for the purposes of referring to the referent.

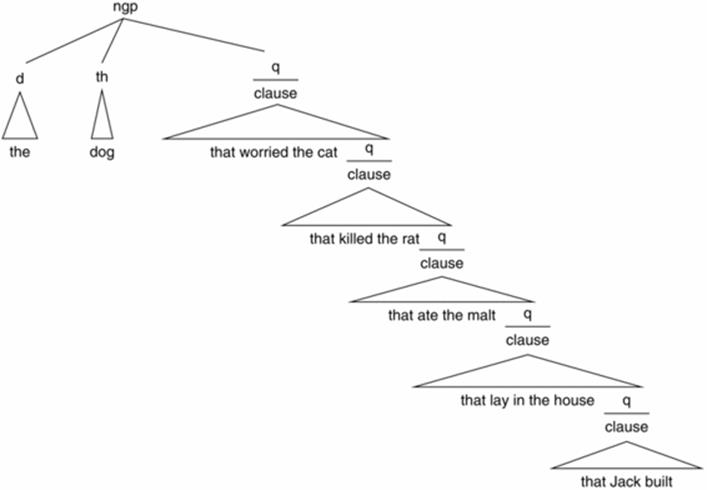

Figure 3.22 The ‘House that Jack built’ example

The qualifier area of the grammar is complex due to the great potential for embedding in this part of the nominal group. As we saw in Chapter 2, there is a very famous example of this kind of embedding in the last line of the ‘House that Jack Built’ example, which is repeated here in (21). The nominal group of interest to us here has been underlined. Clearly, this shows the potential for complexity that is incorporated into the qualifier element. The first level of analysis of the nominal group would show only three elements: dd + th + q. The tree diagram for this nominal group is shown in Figure 3.22. The triangle notation is used here since we have not yet covered the detail on the functions and structures of the clause. We will come back to qualifiers in later chapters once we have considered the clause in sufficient detail.

(21) This is the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built

3.2.4.1 The prepositional phrase

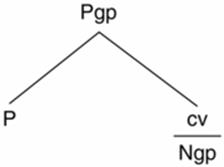

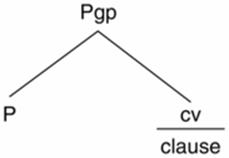

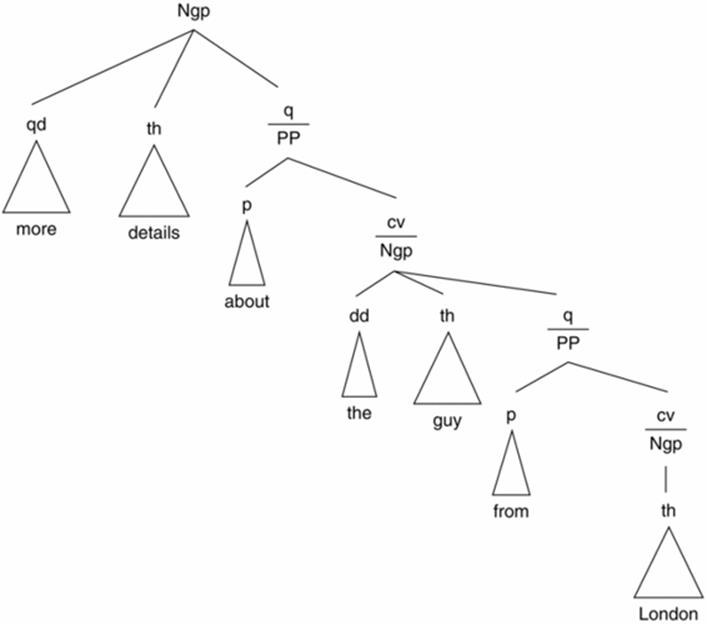

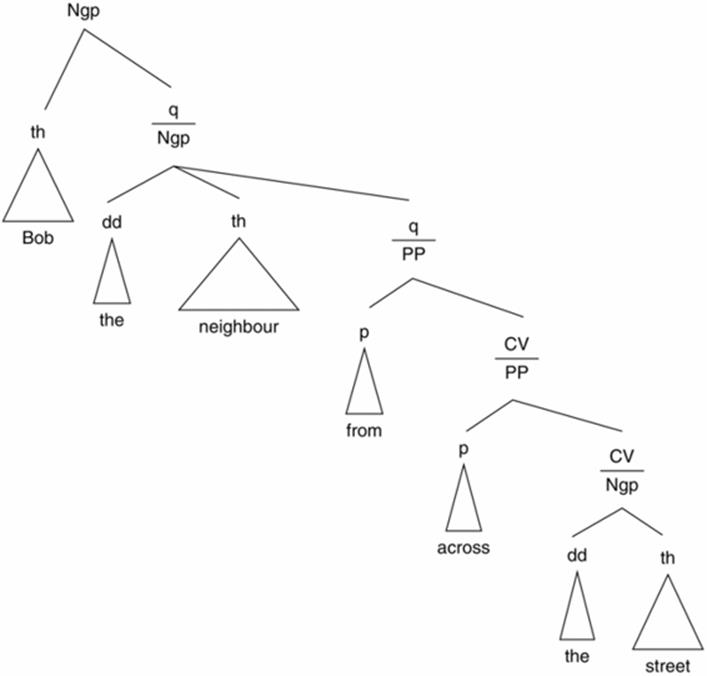

There is one final group that we need to discuss before completing the presentation of the elements of the nominal group. The prepositional phrase (PP) is an important unit for the nominal group for two main reasons. The first is that it is by far the most frequent type of qualifier. So, when a nominal group includes a qualifier, it is most likely that the structure realizing the qualifier will be a prepositional phrase. The second is that the prepositional phrase is similar to the nominal group in the sense that it will very often be used to introduce a new referent. The main element of the prepositional phrase (PP) is a prepositional element (p). This element is almost always expressed by a single preposition (e.g. in, on, with, for, by). However, there are times when the preposition is modified, and in these cases the prepositional element is expressed by a preposition group (e.g. right on the table). In addition to the prepositional element, the prepositional phrase has another element, which is called a completive (cv). The completive is most often realized by a nominal group (see Figure 3.23), although it is also possible for it to be expressed by an embedded clause (see Figure 3.24) or even a prepositional phrase (see Figures 3.25 and 3.26). The distinction between the units of phrase and group was discussed in Chapter 1 and, as explained there, groups are based on a head word plus modifier relationship between elements whereas phrases are based on a relationship of completing. In this sense, the prepositional phrase is more closely related to the composition of the clause than any group unit. Finally, although the prepositional phrase most frequently expresses both the prepositional element and the completive element, it is possible for the completive element to be omitted. There are several references listed in the further reading section at the end of this chapter which will be useful for the keen reader who wishes to explore the theoretical concerns related to prepositions and the prepositional phrase.

Figure 3.23 Completive element expressed by a nominal group, as in in the woods

Figure 3.24 Completive element expressed by a clause, as in by closing the bar

Figure 3.25 Example of qualifier element expressed by a prepositional phrase

Figure 3.26 Example of a qualifier element realized by a nominal group

3.2.4.2 Some examples of qualifiers

In the following two examples, each nominal group includes a qualifier which is post-modifying the thing element. The qualifier is realized in example (22) by a prepositional phrase and in example (23) by a nominal group. The analysis for these is given in Figures 3.25 and 3.26 respectively.This completes the presentation of the structure of the nominal group in this chapter. As we have seen there are some areas that are complex, especially when embedding is involved. One consequence of the role of the qualifier element is that it can be difficult to know where the nominal group ends. There are strategies that can be used to help identify the limits of the nominal group. The next section will explain some of the tests that can be used to help determine the boundaries of groups within the clause.

(22) do provide more details about the guy from London

(23) Bob the neighbour from across the street is golfing with John

3.3 Tests for recognizing nominal group boundaries

This morning, I shot an elephant in my pyjamas . . .

How he got in my pyjamas, I’ll never know!

(Groucho Marx)

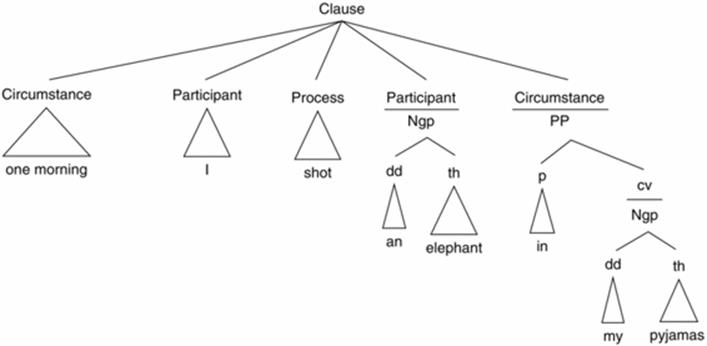

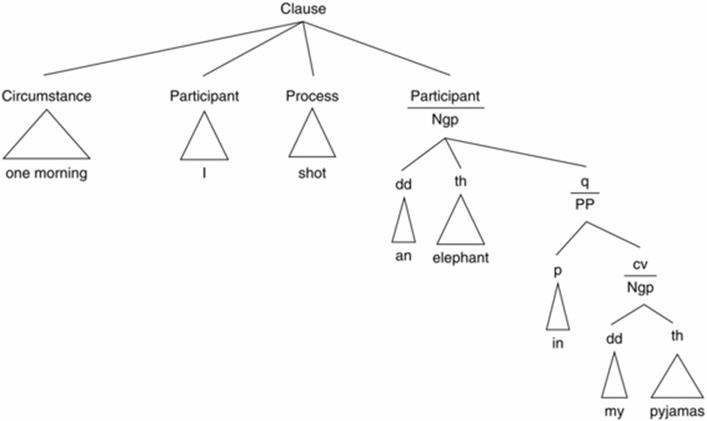

This Groucho Marx joke was discussed in Chapter 1 to illustrate how playing with language this way reveals our understanding of grammatical structure. At the first reading, there would be no grammatical association between the elephant and the speaker’s pyjamas. However, the humour comes retrospectively with the second sentence when it becomes clear that in my pyjamas can be interpreted as a qualifier which describes the referent (

Figure 3.27 Tree diagram with an elephant separate from in my pyjamas

Figure 3.28 Tree diagram with an elephant in my pyjamas as one group

In what follows, we will consider tests that help to identify where the boundaries are for the nominal group. These tests do not help if a clause is ambiguous because the result will be that two different structural representations are possible. However, they can be used effectively when there is uncertainty about the boundaries around a nominal group.

3.3.1 Pronoun replacement (or substitution) test

This test helps you to identify group boundaries, including boundaries around embedded clauses. The test is based on a fundamental principle of personal pronoun use. Personal pronouns do not replace nouns, they replace entire nominal groups. We can use this principle to our advantage to test where group boundaries are (including boundaries around embedded clauses). In theory any participating entity can be replaced by a pronoun (there may be some exceptions to this).

To use this test, consider example (24). The pronoun replacement test will be used to see where the nominal group boundaries are.Since the clause begins with a pronoun, we can be reasonably confident that this is a nominal group; there is no need to replace a pronoun with a pronoun. However, everything following the verb saw could potentially be one nominal group with one or two qualifiers or one nominal group followed by two prepositional phrases. The question is whether on Tolkien is part of the referring expression and therefore expressing the function of qualifier in the nominal group or not. The first step is to attempt to replace the nominal group an expert by a personal pronoun. The result given in (24′) shows that it doesn’t work and therefore an expert cannot function as a separate group from the words that follow. The test doesn’t end here because we still don’t know where the end of the nominal group is. The next candidate is an expert on Tolkien. The results for replacing this group of words with a pronoun is given in (24″) which shows that an expert on Tolkien is a single nominal group and on TV is a separate unit. Within this nominal group, on Tolkien has the function of qualifier; it is modifying expert (i.e. what kind of expert? a Tolkien expert). The prepositional phrase on TV has no direct involvement in the referring expression – it has a function related to the process of seeing (i.e. where the expert on Tolkien was seen).Therefore an expert on Tolkien will have one function and on TV will have a different function with respect to the clause. Within the nominal group, an expert on Tolkien, we find the following elements: dd + th + q. It is certainly possible for on TV to be included within the nominal group, as would be the case for an example such as I know an expert on news reporting on TV, where news reporting on TV is a nominal group within the prepositional phrase on news reporting on TV, which functions as a qualifier in the nominal group, an expert on news reporting on TV.

(24) I saw an expert on Tolkien on TV

(24′) *I saw him on Tolkien on TV

(24″) I saw him on TV

This test can be used in most instances where it is necessary to verify or determine group boundaries.

3.3.2 Movement test

The movement test is similar to the replacement test in the sense that it relies on a principle of how groups work. This principle is that groups can be moved by rephrasing the clause in question. The corollary to this is that generally speaking one part of a group cannot normally be isolated from the rest of it. As with the replacement test, the movement test can be used to help you to identify group boundaries. It can be useful in helping to determine whether a group is realizing a qualifier (in a nominal group) or is a separate group (and therefore has a different function). However, there are instances where, in certain contexts, a qualifier element can be separated from the thing element in the nominal group without sounding odd (see example (25′), for which the movement test does not provide a clear result).

To try out this test, consider example (25).The problem we are faced with is how to sort out the internal units of the clause. After the verb send, the first word we come to is me, which is a personal pronoun, so we can be reasonably confident that this is a separate group. Next we have a noun (information) and a preposition (about) and then an embedded clause (this will be covered in Chapters 5 and 7). We know that prepositions often introduce a prepositional phrase so it is likely that about where you will be is a prepositional phrase. This can be tested by attempting to replace where you will be with a preposition such as that or it. If we do so, we have send me information about that, which shows that the unit in question is indeed a prepositional phrase. However, what needs to be decided is whether information about where you will be is one nominal group, or information is a single nominal group with a separate prepositional phrase, about where you will be, in an adjacent position. We could also apply the pronoun replacement test to see whether a pronoun could replace information. In the movement test, we want to see whether information could be moved elsewhere in the clause. If so, then this indicates information is a group which is separate from about where you will be. If not, then this suggests information is part of another group. There are a number of ways we can move things around in a clause. One is to rephrase the clause in the passive voice. Another way is to rephrase the clause as a cleft sentence. Passivization will only work if the clause in question is in the active voice. The cleft test relies on fitting the units into the grammatical frame ‘It was X that Y’, where X is a single unit (group or phrase) and Y is the remainder of the clause.

(25) Send me information about where you will be

These reformulations are given in (25′) and (25″) below.The result of this test using the passive structure is not as conclusive as the result from the use of the cleft sentence. By combining the results from both attempts, it seems clear that information does not constitute a group of its own. However, for the sake of completion, we should continue with the tests until we have a satisfactory result. In this case, we need to test whether information about where you will be does constitute a single nominal group.The results from this application of the movement test seem clear; information about where you will be constitutes a single nominal group. The constituency of this group is: th + q. The prepositional phrase about where you will be is realizing a qualifier within the nominal group.

(25′) ?information was sent about where you will be

(25″) *It was information that was sent about where you will be

(25‴) information about where you will be was sent

(25″″) it was information about where you will be that was sent

The individual tests may not work on every clause and sometimes a combination of tests is needed to determine the unit boundaries. As we will see throughout this book, these tests are important tools in analysing language. Part of the analyst’s job is to work out relations and functions, and doing so involves being able to manipulate the language under analysis in order to feel confident about the results.

3.4 Worked example of the nominal group analysis

To summarize this chapter on the nominal group, this last section will work through the analysis of nominal groups in a clause. This will consolidate everything we have discussed so far. Upon completion of this section, you should be ready to work on some analysis of nominal groups on your own. You will find exercises at the end of this chapter in section 3.5 and then the answers can be found at the end of this book in Chapter 10 – but of course it is best if you don’t look until you have tried to complete the exercises yourself.

The clause that will be analysed is given below in example (26). It is from an email written by an adult woman to her friend. Since we have not covered how to analyse the clause yet, we will avoid any discussion of details that are not particularly relevant to the nominal group.The first thing to do is look for all the nouns in the clause. This follows on from the principle that where there is a noun there is a nominal group. As we saw in the section above, if we find a pronoun, we will have most probably found a nominal group (except for possessive pronouns, of course, which will always be expressing a determiner function within the nominal group, e.g. my job). Once we identify the nouns, we need to look around the noun for elements of a nominal group. We can use our knowledge of the nominal group to make educated guesses at the nominal group boundaries and then test this using the test discussed insection 3.3.

(26) A friend from John’s lacrosse team met a woman that way

We will now work through the analysis for example (26).

· Identify all nouns.

A friend from John’s lacrosse team met a woman that way

· Look for elements typically found in nominal groups.

|

A |

friend |

from |

John’s |

lacrosse |

team |

met |

a |

woman |

that |

way |

|

dd |

th |

p |

dd |

th |

th |

dd |

th |

dd |

th |

|

|

Ngp |

PP |

Ngp |

Ngp |

|||||||

This shows that the first nominal group begins with a friend but that we have not yet determined where this nominal group ends. The next group of words seems to form a prepositional phrase but we don’t know yet whether it is a qualifier in the nominal group beginning with a friend or whether it is a separate group. Similarly, two nominal groups have been found but it isn’t clear whether they combine in a single nominal group or represent two separate groups.

· Use tests to determine group boundaries.

Replacement test: test a friend and from John’s lacrosse team:

*He from John’s lacrosse team met a woman that way

He met a woman that way

Therefore a friend from John’s lacrosse team is a single nominal group and the prepositional phrase from John’s lacrosse team is realizing a qualifier in that nominal group.

Movement test: test a woman and that way

A woman was met that way

*A woman that way was met

It was a woman that he met that way

*It was a woman that way that he met

Therefore a woman is a separate nominal group from that way and they have different functions with respect to the clause.

· Determine the structural organization of the nominal groups using information about the functions of the nominal group elements.

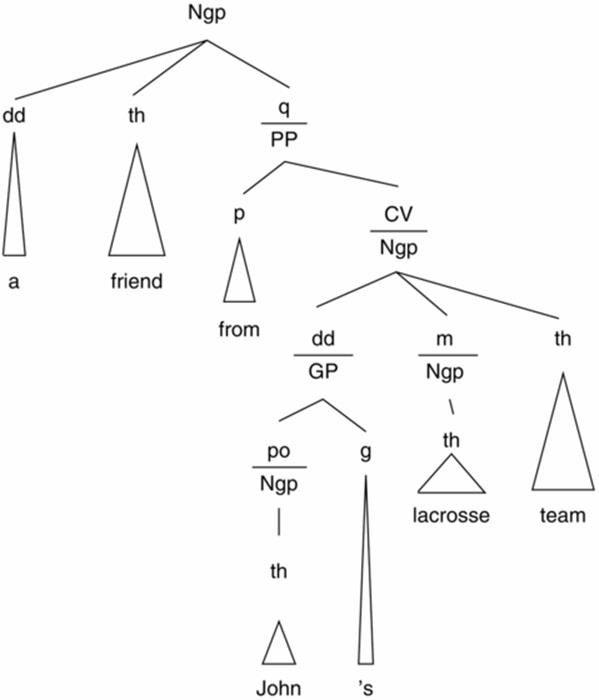

· Draw the tree diagram for each noun group (see Figures 3.29 to 3.31).

This approach should work for any nominal group although, as stated above, not every test will work on every clause. The approach will change slightly once we have covered everything needed for analysing the clause. For example there would be no point in drawing tree diagrams for all nominal groups; instead they would be included in the tree diagram for the clause as a whole.

Figure 3.29 Tree diagram for a friend from John’s lacrosse team

Figure 3.30 Tree diagram for a woman

Figure 3.31 Tree diagram for that way

Although we have come to the end of the chapter on nominal groups, this is not the end of the discussion about them. We will build on this foundation in the next few chapters as we develop our understanding of the three main metafunctions of the clause.

3.5 Exercises

Exercise 3.1

In the following brief text (personal email from 26 June 2010), identify all the nominal groups you can find.

I do have asthma. I’m not getting enough oxygen into my bloodstream. I must find a doctor.

I hope that things are on the mend now for Rowan. It’s good that he is being checked out so well. Hopefully the chamber thing will deliver the meds better and get to the problem. Breathing problems are so weird. One of the most important things that I’ve learned is staying calm. There is an automatic response to get excited when unable to breathe, and the added stress makes it more difficult to breathe.

link to answer

Exercise 3.2

In the following three clauses, analyse the underlined nominal groups and draw the tree diagram.

1. some symptoms were still present

link to answer

2. they gave out a couple of awards

link to answer

3. enjoy the extra hands around the flat

link to answer

link to answer

3.6 Further reading

On the nominal group:

Bloor, T. and M. Bloor. 2004. The Functional Analysis of English: A Hallidayan Approach. 2nd edn. London: Arnold.

For further reading on modifiers and the adjective group:

Tucker, G. 1998. The Lexicogrammar of Adjectives: A Systemic Functional Approach to Lexis. London and New York: Cassell.

On selection and the selector element:

Fawcett, R. 2007a. ‘Modelling “selection” between referents in the English nominal group: an essay in scientific inquiry in linguistics’, in C. Butler, R. Hidalgo Downing and J. Lavid, eds., Functional Perspectives on Grammar and Discourse: Papers in Honour of Professor Angela Downing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins: 165–204.

On the distinction between group and phrase and the differences between prepositional phrases and prepositional groups:

Fawcett, R. 2000c. A Theory of Syntax for Systemic Functional Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Halliday, M. A. K. and C. Matthiessen. 2004. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. 3rd edn. London: Hodder Arnold.