Essential Writing Skills for College and Beyond (2014)

Part I. IDEA-GENERATION STRATEGIES

Chapter 1. Getting Started and Developing Your Ideas

“Where do I start?”

Students ask this question more than any other, and it’s definitely an understandable one. Indeed, for many writers, one of the hardest parts of writing is getting started.

Facing the blank page can be intimidating, especially when you know someone will grade your ability to write well. Yet you have to start at some point, so I will pass on to you one of the most helpful pieces of advice I have received on writing: Begin by beginning.

If you think that sounds simple, you’re right—and you’re wrong. Beginning can be easy, but it can also be quite difficult. All writers, whether they are beginners or experts, experience blocks, so don’t panic if you can’t immediately think of a dozen ideas for your paper.

There are many ways to start writing a paper, but there is not one right way.

You will find in this chapter several strategies that writers (from beginners to professionals) use to help them get started in the writing process. Use some or all of these strategies; one may work well for you on one assignment but not another. Use the ones that work best for you.

As you write, keep in mind that the ultimate goal of any paper is to explain the topic to yourself. Yes, professors assign papers because they must, but the goal of any assignment is to elicit student thought on a particular topic, text, or theory. Remember the base of academia: the quest for knowledge. When you can explain your theory to yourself so well that you fully understand it and could teach it to others, then you probably have composed an excellent essay.

How do you achieve this feat?

Remember, begin by beginning. Don’t worry about whether what you have written is “good” or not; just write. You can edit and polish later. The important thing is to get started.

THE CRITIC

The Critic is one of the first barriers writers must face. It’s that internal voice that tells us our writing is useless, embarrassingly bad drivel that does not deserve to see the light of day, let alone earn credit.

The Critic may manifest itself in the likeness of a former English teacher, a hard-to-please parent, or even yourself. The bad news is that The Critic’s voice will not likely disappear, no matter how much or how long you write. The good news is that when used wisely, the voice of The Critic can actually help you become a better writer.

Jack Heffron, author of The Writer’s Idea Book, suggests listening to the voice of The Critic, but only after the first draft is composed.

When The Critic appears, ready to rip your work to shreds, assure him that he will have his say, but not yet. After the draft is completed, The Critic can offer feedback, but not before.

When you learn to control when and how The Critic addresses your work, he will become your friend rather than your enemy. As Heffron points out, The Critic is a necessary voice at times because he can push you to improve your work and increase your ability to recognize strong, powerful writing.

When you hear the voice of The Critic telling you your idea is stupid, your writing dull and pedestrian, tell the voice to wait. He may indeed be right. And he will have his turn, you promise, but it’s not his turn now. The early draft is no place for The Critic. If he insists on interfering, try not to fight him directly. Instead, observe the voice, name it “The Critic,” and let it go. … Send him to a movie or on a nature hike or into the other room. He’ll probably pop his head in from time to time, asking, ‘Ready for me yet?’ In as kind a voice as you can muster, simply say, “Not yet.” (Heffron 19)

So, give The Critic his say, but only when you are ready to edit and revise—not when you are just beginning. His help is only required after you’ve composed.

Consider, for example, the case of Stephen King and his now-famous novel Carrie. This world-famous, award-winning writer of fiction and nonfiction books, as well as several short-story collections, apparently had a rough case of The Critic, too. Before he was famous, before he won any awards, he doubted his abilities just like the rest of us. In fact, his inner critic assessed Carrie and determined it so entirely useless that King finally just tossed it into the garbage.

Luckily, King’s wife fished it out and encouraged him to keep working on it. This decision garnered him his first publication, which led to another and another, and eventually to fame, wealth, and a decades-long writing career—and all from a story his inner critic told him to scrap. This trashed story, in fact, has since been adapted into feature films, a television film, and even a musical. Not bad for “garbage.”

If King had listened to The Critic’s harsh judgments, he would probably not be the rich, successful, famous writer he is today. Instead, he temporarily silenced this voice and later used it to his advantage to improve the work. You can, too, if you learn to control your Critic.

Never let The Critic talk you out of writing. Only let him help you improve what you have already written.

Great and successful writing begins with getting ideas onto the page or screen. You can go back and polish, delete, tinker, and improve later.

Remember, allow The Critic to have his say only when you are ready to edit and revise. (For more on controlling The Critic, see chapter 8.)

On the next few pages, you’ll find several brainstorming and freewriting ideas that will help you to do just that—get started and generate ideas that will lead to full-length essays. Don’t worry about the strength or brilliance of your ideas at this point. Simply write. Generate the ideas first. Revise and edit later.

FREEWRITING

You’ve probably practiced freewriting before, either in your personal writing, in high school, or in college classes. Freewriting is exactly what it sounds like: writing freely. Write whatever comes to mind, in whatever order it comes. Don’t censor. Just write.

Some writers believe speed is the key to this technique. They believe writing as quickly as possible works best. If writing quickly works for you, then by all means do it. If you prefer to write at your regular pace, then try that as well.

The key to freewriting is to write without stopping and without censorship. This means you simply write without worrying about grammar, spelling, punctuation, logic, organization, and so on. All that matters is that you allow the ideas to flow. Absolutely no censorship. Editing comes later.

If you think the idea is stupid, write it anyway. If the idea seems off-topic, write it anyway. If you get stuck, keep writing anyway; even if you write, “This is stupid; this isn’t working. I can’t think of anything to say,” eventually ideas will begin to flow as your mind realizes it has free creative reign.

Try this strategy both with pen and paper and on the computer to see which method works best for you.

Remember, the aim of freewriting is to get your ideas onto the paper or screen. You can’t do that if you’re thinking about the quality or scope of the ideas, so try not to judge or evaluate as you write. Let your ideas flow onto the page or screen. You’ll have plenty of time to delete, edit, or revise later.

If you tend to be a highly critical or perfectionist writer, this task may be difficult. But keep in mind that you will not be turning in this portion of the paper and there is always time for refining and buffing later.

FREEWRITING STRATEGIES

FOCUSED FREEWRITING: Sit down with a blank page or screen. Focus your attention on your assignment, topic, or prompt. Write nonstop for at least five minutes (ten to fifteen minutes seems to work well for most people) without censoring or judging your ideas except to remain focused on your topic. As long as the idea relates to your topic, write it down—even if it doesn’t seem very worthwhile initially. Stop when you run out of language, your hand cramps, or you run out of ink. Repeat as desired.

FREE FREEWRITING: Sit down with a blank page or screen in front of you and start writing. Write whatever comes to mind, whether it pertains to your topic or not. Just write. The ideas or worries swimming around in your mind will be released onto the page, and once this release occurs, your mind is free to unleash the depths of its abilities. Stop when you cannot write another word, the keys on your computer are stuck due to overuse, or your brain has decided to shut down. Repeat as desired.

TIMED FREEWRITING: Sit down with a blank page or screen. Set your phone, kitchen timer, or watch for a specific time. Some writers prefer five-minute increments, others twenty or more minutes, but try to work for at least five minutes. You can increase the time as you get better with this technique. Write freely or focus your writing on a specific topic; just write nonstop without censoring or judging your ideas until your timer releases you. Repeat as desired.

Note the difference between “focused” and “timed” freewriting: When you complete the former, you must remain focused on your topic; when you try the latter, you simply write and allow any ideas that occur to you to have free expression—even if these ideas initially seem off-topic. They may be, or they may not. Just write, and see what happens.

If you are writing about two time periods, theories, books, or paintings in a single paper, it can help to do a timed freewriting session for each. For example, if you have to analyze two characters, choose one to focus on first and write or type the character’s name at the top of the page. Then while timing yourself, write everything you can think of about your subject. Once your time expires for that character or theme, repeat the process for the other one(s). This process works with multiple ideas, theories, paintings, historical figures, and the like.

WORD-ASSOCIATION FREEWRITING: Write your topic or a keyword from your topic in the center of the page, and then write whatever comes to mind about it. If your assignment asks you to write a biography about an author, scientist, or painter, for instance, write the author’s name in the center of the page. If you’re writing about characters, use this technique for each character. If you’re asked to write about a certain theory, write the keywords in the center and then write everything that comes to mind about it. This technique forces your knowledge and ideas onto the page and will give you a clear assessment of what you already know and what you do not. Don’t worry about wording or organization. For now, just allow the ideas to express themselves; in other words, just get it all out.

The following example demonstrates Kim’s timed, focused freewriting for analyzing the character Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

OPHELIA

She is young and pretty, but she seems sad. Don’t really know what to say about her. Is she having an affair with Hamlet? What’s the deal with them? This play was hard to read! I’m stuck. Well, she kills herself, I think. But I don’t think she does it just to get attention like that guy in our class said. I think she was trying to say something. Her dad seems nosy and in her business too much, and her brother also seems pushy and overbearing. Maybe she was tired of her dad and brother running her life. They always seemed to be telling her what to do, and then Hamlet tries to tell her what to do and then he dumps her. Maybe she felt isolated and abandoned by all the men in her life. It seems like she is maybe fifteen or sixteen, but she doesn’t really have any say in her life; she has to do what everyone else tells her. Maybe that’s what Shakespeare’s trying to say, that she is controlled by everyone around her and the only way she could gain any power and control in her life was to end it? Yeah, maybe her suicide shows that she felt the only way she could be free was in death.

I guess that would go with the whole “something’s rotten in the state of Denmark” thing that we talked about in class. She’s part of the rottenness? Or maybe the way people treated her was the rotten part? I’m not sure, but I guess I need to get that quote about rotten stuff from the play. … What does Ophelia do or say right before she commits suicide? Maybe I could use that as evidence. And am I sure she killed herself? I guess I need to check on that. Then I could try to prove that her suicide means something and has something to do with all the control they all had over her and somehow tie it to the whole rotten thing.

This writer has generated several ideas to explore for her paper:

1. How feeling subjugated affects Ophelia and leads to her death/suicide

2. Ophelia’s depiction as related to the theme of power that runs through the play

3. Why understanding Ophelia and her actions is important to understanding the play as a whole and the “rottenness” within it that many scholars address

BRAINSTORMING

Like freewriting, brainstorming is a method writers use to help them generate ideas. When brainstorming, you will write all the ideas that come to mind, just as you did in freewriting, but it will be a bit more organized than freewriting. Brainstorming often results in a list, chart, or map.

There are many, many different types of brainstorming. You will find on the following pages the most widely used brainstorming strategies and examples of each. Some of these techniques may work for you, but others may not. Keep in mind that some writers do not like or use brainstorming at all and prefer to begin simply with cold writing. Neither method is “right” or “wrong”; find what works well for you, and use it.

You’ll notice that the brainstorming strategies are divided into two groups: visual spatial and linear.

Brainstorming is most effective when writers use both linear and visual spatial strategies. Why? Using different types of writing strategies engages different areas of the brain.

Employing both “right” and “left” brainstorming techniques engages both sides of the brain, which doubles your brainpower and leads to more insightful and creative expression.

Since the left side of the brain controls writing and language, most beginning writers approach assignments only with left-brain strategies, such as writing sentences and paragraphs. Although this can be a successful strategy, engaging the right brain, too, will help elicit new, different ideas and ways of viewing the topic. The right brain controls spatial relationships and the imagination, so strategies such as the idea map or the Venn diagram can prove helpful for getting the right brain working on your topic. Indeed, many successful writers use both linear and visual spatial strategies when they approach an assignment so that they can tap into both right- and left-brained perspectives.

When you finish brainstorming, it may be helpful to see the end of this chapter for suggestions about how to use the ideas you solicited with your brainstorming techniques.

Like freewriting, brainstorming proves a helpful tool for writers at any point in the writing process. However, most writers find brainstorming especially helpful at the beginning of an assignment, when they need to get started and generate ideas.

It often helps to reread the prompt or assignment just before beginning your brainstorming session to ensure you have a firm grasp of what the assignment asks you to do.

You might choose to set a timer for your brainstorming session, depending on how well you work under pressure. If setting a specific end time seems to work well for you, then try that; if not, keep brainstorming until your page or diagram is full.

In the following sections, we will focus on these strategies:

LEFT BRAIN (LINEAR)

· Lists and Outlines

· Question and Answer

· Reporters’ Questions

· Cubing

RIGHT BRAIN (VISUAL SPATIAL)

· Idea Map or Web

· Cluster

· T-chart

· Venn Diagram

You may not necessarily use all the ideas you elicit in your brainstorming, but at this point don’t worry about restricting yourself to two or three main ideas. Just get your ideas stirring. In the beginning stages of a writing assignment, the more ideas you can generate, the better. Greater selection in the early stages of writing usually leads to greater creativity and depth of thought while brainstorming. Besides, having a long list of ideas from which you can choose is always better than scrambling for ideas later as you try to write the essay itself.

Don’t feel like you have to try each of these brainstorming strategies for every single paper you write; the technique you use for each assignment is ultimately up to you, so feel free to experiment with different techniques. However, certain strategies do lend themselves to certain types of assignments, so you may find it helpful to see the “Idea Generation Strategies at a Glance” chart found later in this chapter, which indicates which strategies are recommended for the different types of writing assignments.

VISUAL-SPATIAL BRAINSTORMING STRATEGIES

Try the following right-brain strategies to engage your right hemisphere. If you are typically a left-brained person, these may be difficult at first, but using them will help strengthen your right hemisphere, which will improve your brain’s ability to process and elicit information.

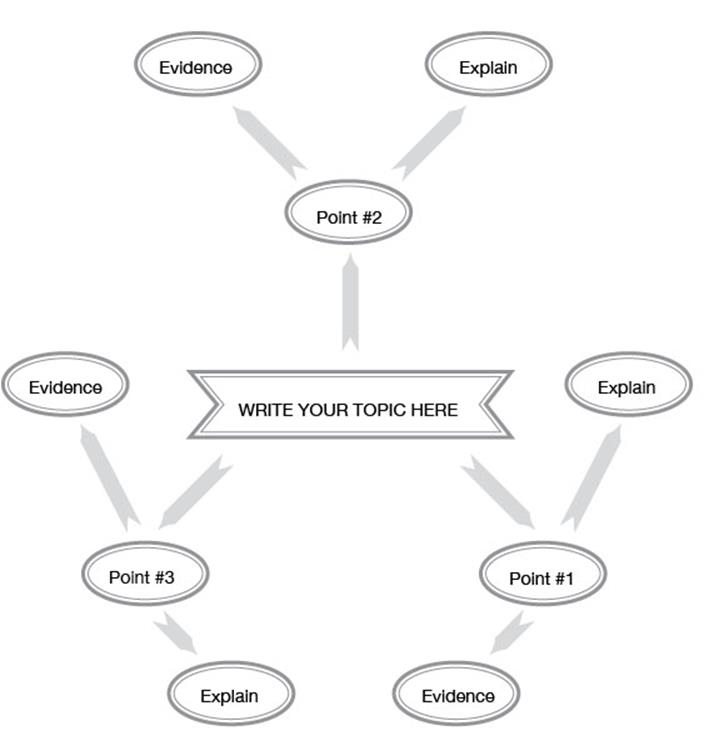

THE IDEA MAP OR WEB

The idea map (or idea web) remains among the most popular right-brain idea strategies because it works well to get ideas flowing and its structure makes converting your ideas to linear paragraphs a breeze. An idea map is exactly what it sounds like: a map that outlines your ideas. It nicely organizes your ideas on the page and reveals the connections between them.

To create one, write your topic in the center of the page and then write a major point in each of the three circles stemming from the center circle. Then write supporting information (such as evidence and explanations) in the smaller circles stemming from your point circles. You can draw as many or as few circles as you like, and don’t worry if you do not fill in all the circles or if you need to add more circles. Just focus on getting your ideas onto the page.

Once you’ve completed your map, sit back and look at it; you’ll instantly see the type of information you have in abundance and what you lack. For example, do you have many points but little explanation and evidence, or is the reverse true? Either way, the idea map will clearly illustrate this information to you and will point to the areas that need further development. Take your strongest points from the idea map, and convert each into its own body paragraph.

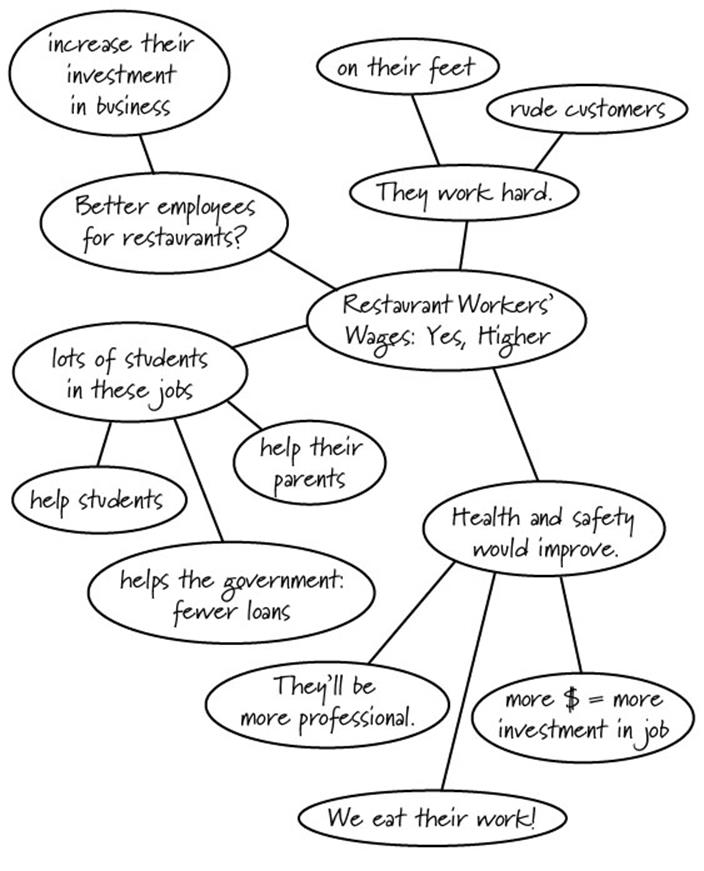

This idea map, created by Russell, shows his brainstorming for an essay on wage increases for restaurant workers.

T-CHART

Different writers use the T-chart differently, and its flexibility is one of its greatest assets for writers. The T-chart works well for comparison/contrast, pros and cons, or proponent/opponent assignments because it allows you to immediately see connections or differences between ideas or topics. It also identifies the topics or ideas you will need to flesh out more thoroughly. To create a T-chart, follow these steps:

1. Draw a Giant T on a piece of paper, or if you prefer to use a computer, create a table.

2. Write or type your first topic, text, character, or perspective on top of the column on the far left side of the page or screen; then write or type your second topic, text, character, or perspective on top of the second column, and repeat the process to add as many columns as you need.

3. Decide in which column you should begin, and then write everything that comes to mind about that topic, text, or character. You can time yourself if you like. Some writers set a timer for five to seven minutes, write in only one column the entire time, and then repeat the process for each column. Other writers simply write until they have filled each column or come up with a predetermined number of ideas.

4. Repeat this process in each of your columns.

This is a T-chart created by Jenny, who is writing on the topic of comparing and contrasting the depictions of two characters in similar familial roles in a film or television text.

|

PETER GRIFFIN (FAMILY GUY) |

HOMER SIMPSON (THE SIMPSONS) |

|

· Idiot · Fat · Lazy · Incompetent at job, goes through several jobs · Spends a lot of time at the bar · He is mean to his daughter, Meg, and seems like he could not care less about her. She is the family joke, and he encourages this. There are lots of episodes where he makes fun of her and calls her names. · He is mostly uninterested in the other kids unless they can do something for him; he spends more time with his friends than with his kids. · Peter treats Lois horribly; he is a terrible husband. I don’t know if he ever actually cheated, but I think he would if he had the chance. I need to check on this. He and his friends check out other women all the time, which shows he sees marriage as a joke and doesn’t take it seriously like Homer does. |

· Idiot · Fat · Lazy · Incompetent at job, but keeps the same job for most of the show · Spends a lot of time at Moe’s. (Does he spend as much time as Peter does? I need to check on that...) · He is nice to Lisa (most of the time, lol), encourages her a lot, and loves her; he wants the best for her. He sees her as the best thing he ever did and is a good father to her. · He fights a lot with Bart but has a definite connection and bond with him. There are lots of episodes about them doing things together. · I think Homer spends more time with his family than with his friends, definitely more than Peter spends with his family. · Homer is a good husband overall. He does not cheat on Marge, even when he has the chance. He and his friends don’t really talk about and look at other women; do they? Need to check … |

Jenny notes a couple of items she must verify within the texts; even though she is unsure of their accuracy, she has generated some excellent starting points. Even if all of her perceptions do not pan out, she will be in good shape because she has listed plenty of ideas here.

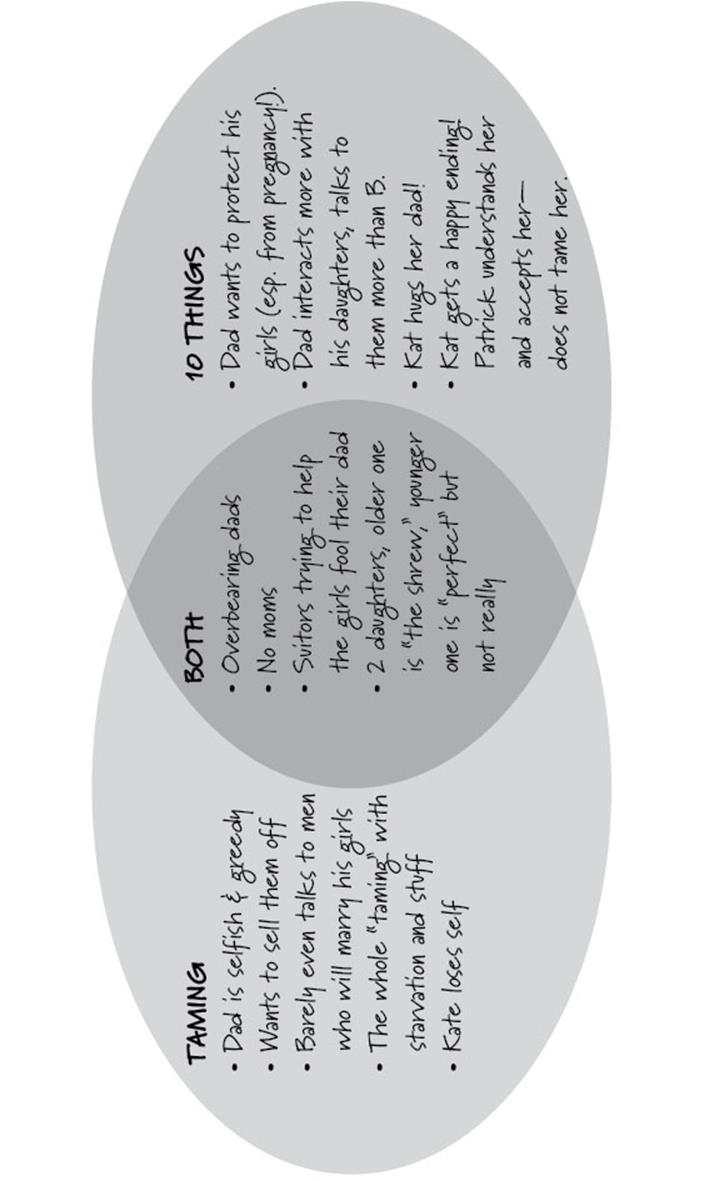

VENN DIAGRAM

The Venn diagram, like the T-chart, allows writers to easily compare and contrast ideas, topics, concepts, people, characters, time periods, paintings, and so forth. The Venn diagram helps writers examine the relationships between ideas so that the distinctions and/or overlaps within the concepts, patterns, or depictions become clear.

Like the T-chart, the Venn diagram will immediately reveal to you which topics you know the most (and least) about, and it will also clearly illustrate whether you feel the ideas or texts you compare have more differences or similarities. To create a Venn diagram, follow these steps:

1. Draw a large circle near the left margin of your page or document; extend the circle toward the middle of the page.

2. Draw another circle near the right margin of your page or document, but be sure its outer left side overlaps the outer right side of the first circle. In other words, the circles should connect to each other.

3. If you have three topics to compare or consider, draw a third circle on the bottom or top of the two original circles so that it, too, overlaps each of the two original circles. (Add one circle for each major idea you must examine, making sure each circle is connected to all others.)

4. Once the circles are drawn, write the first idea, topic, or perspective you must consider in the center of the first circle. Write this topic in bold or black, or underline it. Then repeat the process with each idea, topic, or perspective you will cover in your essay.

5. Start with whichever circle you like, and write everything that applies to that topic—and only that topic—within it. Don’t write in the overlapping areas just yet.

6. Once each major circle is filled with ideas, move to the overlapping areas between the circles. These areas represent the shared characteristics, so now write in these spaces the commonalities of the topics or ideas. In other words, write what is true of both of the ideas or texts represented by the intertwined circles.

This process probably sounds complicated at first, but it’s not too difficult once you see it in action.

This Venn diagram, created by Robin, compares and contrasts the depictions of father/daughter relationships in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew and the modern-day movie 10 Things I Hate About You.

LINEAR BRAINSTORMING STRATEGIES

Try the following left-brain linear brainstorming techniques to engage your left hemisphere. If you are typically a right-brained person, these may be difficult at first, but using them will strengthen your left hemisphere, which will improve your brain’s ability to process and elicit information.

REPORTERS’ QUESTIONS

Using reporters’ questions (“Who?” “What?” “When?” “Where?” “How?” “Why?” and “So what?”) to get ideas for a paper can be immensely helpful because doing so immediately reveals which areas of your paper need more information.

Each question may not apply to every assignment or text you are writing about, but the process reveals which questions you can immediately answer and which you cannot. For example, if you can easily answer “Who?” and “What?” but not “When?” or “Why?” you know you need to go back through your materials and see if you can or should figure out the answers to these questions. If not, that’s fine, but the act of researching will build your knowledge of the topic and will lead you to other answers that you can include in your essay.

When answering reporters’ questions, keep the following questions in mind:

· Who is involved in this topic? Who is affected? Who would care about it?

· What is/are the topic(s)? What are its implications? What are the outcomes and important points to consider?

· When will the issue be important? Is it contemporary and pressing? Timeless and classic?

· Where is the issue most important? Is a certain area or geographical location of particular importance?

· How will the information be presented in your essay? How will you organize your argument, data, or comparison? How will you evaluate the sources you must include? How are you and your readers affected?

· Why is this issue important to consider? Why does it matter? Why would anyone want to read your opinion about it? Why are your ideas significant, unique, or of great value to readers?

· So what? Why should anyone give their interest and attention to this topic and your ideas on it?

The last question—“So what?”—is among the most important to address in an academic essay, and hopefully you noticed that it encompasses most, if not all, of the other questions. Your “So what?” answer is your smoking gun, so to speak; if the answer to this question is compelling, you’ve already set up your essay for success.

Read Russell’s Reporters’ Questions exercise below. Do you think he made an effort to elicit ideas on the topic?

Who?

Restaurant workers

What?

Pay and whether their pay should be raised

When?

??? Now, I guess.

Where?

In restaurants

Why?

???

So what?

No idea

These exercises only work if the writer truly puts her mind to coming up with ideas on the topic. It can be difficult to do sometimes, especially if the topic is one in which you have no interest. Clearly, Russell struggled with this particular topic.

If this happens to you, remember that you have options:

1. Switch the topic to one you find more interesting.

2. Ask for help; go to the instructor, to the TA, to your campus writing center, to a learning lab, or even to a friend or family member.

Russell opted for the second choice and decided to seek his professor’s help. He wanted to do well in the class but just could not come up with many ideas on the topic. Below, you can see the comments the instructor made.

Who?

Restaurant workers

Good—you have identified a specific group, but which restaurant workers? Do you mean managers, CEOs, waiters, hostesses, and bartenders? Specify which workers you will address; the assignment calls for a discussion of tipped employees, so you will probably want to focus there.

What?

Pay and whether their pay should be raised

All you have done here is repeat the prompt. Take a stand: Yes or no? What is your stance? Why?

When?

??? Now, I guess.

“When” may or may not matter too much in your argument; if you want to take a historical perspective and compare wages of these employees now to another time period, it might be interesting or it might not. You’d have to look into this.

Where?

In restaurants

All restaurants in the world? The assignment calls for a discussion of U.S. tipped employees, so try being more specific.

Why?

???

Explain why you feel the wage should be raised or not. What is your evidence? Why do you think as you do?

So what?

No idea

Who is affected by this potential raise besides the employees? What is the impact of giving the raise—or of denying it? Why should readers care about this issue at all?

Here is the resulting page from Russell’s next brainstorming session.

Who?

Servers, bartenders, and cooks because they’re the ones who handle our food and drink directly. Also, people who eat in restaurants, so restaurant customers are a who, too …

Also whoever decides whether they get the raise or not. Their managers or owners? The customers? Not sure...

What?

Raise their pay

Their hourly pay is too low for all the work they do: $2.13 per hour is ridiculous.

When?

Now versus in the past.

A historical perspective might be good.

From Google: This comes from some federal law back in the day that said their pay should be half of the minimum wage. Because they get tips, they don’t need the whole hourly minimum wage, but they should get half of it to make sure they can pay their bills and stuff. That makes sense. I think that’s going to be my argument: Their wage now should be half of the minimum wage now, too. It was then, so why isn’t it now?

Why doesn’t it just automatically go up like minimum wage does? Has anyone tried to get it raised?

Where?

The United States. I wonder if maybe other countries or even different states have different policies on this, and if they do pay their tipped people more, are their restaurants better and safer somehow?

Why?

Why should we raise their pay?

I guess food safety is really the big thing. I think if we pay them more, they’ll do a better job and work harder to make sure our food is safe. Maybe we could make them get certified in food safety or something as a condition of the pay raise?

So what?

I guess this is what I already said about the whole safety thing. I think this might be the best angle to get readers to care, especially if they are not working for tips. They might get mad and think it’s going to cost them more, so I better talk about that.

LISTS AND OUTLINES

Making a list or outline of your topic or ideas can help generate more ideas, and it can also help you get organized.

The List

The list can often lead to the formation of the outline. Whether you use full sentences or just jot down ideas, the list can help you explore the topic and your thinking on it. The list can also work as a sort of to-do command sheet for approaching the paper.

Some writers simply write or type their topic on a blank sheet of paper or on the screen and then type all the ideas that come to mind. (Don’t worry about organizing yet.) Other writers like to break down the topic by paragraph and make a list for each. Still other writers come up with ideas first and then make a list from each idea. Try one or all of these methods to see what works best for you and your writing.

The Outline

An outline provides the writer with a clear trajectory, or a skeleton, of the paper’s organization. The outline should indicate what each paragraph will prove (or even what each sentence will prove, depending on how detailed you wish to make the outline).

As with the list, the outline varies by writer. Some writers compose an overall outline of the paper’s goals and points, while others outline each paragraph separately and in great detail, specifying (sentence by sentence) exactly what information will be covered.

In Russell’s sample brainstorming below, he tried the listing brainstorming strategy while writing a persuasive essay about whether or not a specific group of tipped employees should be granted a federal hourly wage increase. To see how he used this brainstorming to write an essay, turn to chapter 2.

Raise the wages of restaurant workers:

· Restaurant workers work really hard and have to deal with the public.

· Their work can affect our health; we need to make sure our food is safe.

· More money for these people means better food quality and standards in restaurants. Quality costs.

· People enjoy eating out. It reduces stress, which probably leads to a calmer population, which may even reduce crime.

· Restaurant workers’ service provides people a neutral space where they can meet and form associations with others, whether in business or personally.

· Not everyone tips, so they sometimes might miss out on money they have actually earned.

· Paying them more would help the economy because it would put more money in circulation.

Possible arguments against:

· Shouldn’t these workers be clean and handle food properly anyway, without getting a raise?

· How will restaurants pay for this wage raise? Owners will fight this idea.

· They’re not doctors or scientists working on our top diseases or problems, so why should they get more money?

· Couldn’t people form associations somewhere else? What do the servers have to do with these associations?

My rebuttals:

· Restaurant workers should be clean and handle food properly, but better pay usually encourages professionalism.

· What kind of money are these restaurant owners making? If they are almost broke and can’t afford to pay more, that’s one thing, but it seems like they’re doing pretty well. If they have tons of money, then why can’t they pay their workers more than $2 per hour?

· It’s true that restaurant workers are not performing brain surgery. But like I said, their work does affect the public’s health. There are lots of people who aren’t solving our great problems, and they make tons of money. Isn’t food safety worth more than $2 an hour? I’m not saying they should be millionaires.

· Having someone wait on you in a neutral territory is important when forming associations with others. If someone’s your enemy, you’re not going to go to his house and have him wait on you. You need a neutral place run by neutral people.

QUESTION AND ANSWER (Q & A)

Try the following exercise either to help gather ideas or to further specify them. You can follow the recommended time limits (given within the parentheses) if you wish, or simply write until you are tired or out of ideas.

The key to this exercise is to be honest and avoid censoring your ideas. Answer as many or as few of the questions as you wish, but try to write or speak for at least fifteen minutes total.

1. Write or talk about your current essay overall. Specifically, answer the following question: What I am really trying to say in my paper? (seven minutes)

2. What is the primary evidence I examine in my paper? (five minutes)

3. Why do I think this evidence is significant? Why will my readers find this evidence significant? (five to seven minutes)

4. What is the first text’s (essay, book, poem, short story, film, research study, painting, composition, etc.) primary message or theme? Why do I think this? (five to seven minutes)

5. What is the second text’s (essay, poem, short story, film, research study, painting, composition, or short story, etc.) primary message or theme? Why do I think this? (five to seven minutes)

6. What are the biggest questions I still have about this essay? (five minutes)

7. What are my next steps for this paper (such as visiting my instructor during office hours, making an appointment with the writing center, rereading my class notes, or writing out a timeline for completion)? (five minutes)

Once you answer these questions, you will have an excellent idea of which elements of the assignment you have mastered and which you have not. Question 1 addresses points; question 2 addresses illustrations; question 3 addresses explanations. You will learn more about each of these three crucial elements (Points, Illustrations, and Explanations, or “P.I.E.”) in chapter 3.

Below is Kim’s Q & A on the topic of analyzing the character Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

1. What am I really trying to say in my paper?

What I’m trying to say is that I think Ophelia killed herself and that her suicide gives us an important message. Umm … what is the message?? I think the message is something like she couldn’t take the rottenness anymore or something like that. She felt so controlled by everyone else and so overwhelmed by all the horrible things that were everywhere around her, like murder and revenge and incest, that she just couldn’t stand to live anymore. It literally drove her crazy. I think that is what I’m trying to say, that Ophelia killed herself to avoid the rottenness of Denmark.

2. What is the primary evidence I examine in my paper?

I’m looking at other scholars’ ideas about Ophelia and what they think, especially about her death or suicide. I think I should find some other people who also think she committed suicide so I can show that other people agree with me. So far, lots of other people say this, too, but they think she did it for different reasons than I do. I’m not sure if that matters or not.

3. Why do I think this evidence is significant? Why will my readers find this evidence significant?

I have to include research to support my argument, so I have to have people who agree with me, but I was also thinking about bringing in some people who don’t agree and then talking about why I think they are wrong. I think readers will find this significant because it will show them why my argument actually makes more sense and presents more evidence than the opposing views.

4. What is the first text’s (essay, book, poem, short story, film, research study, painting, composition, etc.) primary message or theme? Why do I think this?

I’m only using one text, Hamlet, and I think the main message is don’t try to get revenge on people because it will just backfire and ruin your whole life and everyone else’s life, too. People in the story went crazy, killed each other, and almost everyone dies. I think Ophelia’s suicide really shows how terrible things got there just because Hamlet wanted revenge.

5. What is the second text’s (essay, poem, short story, film, research study, painting, composition, or short story, etc.) primary message or theme? Why do I think this?

N.A. (This question should raise a red flag for Kim; she writes that the question does not apply to her because she is only writing about one text, Hamlet, but she should double-check the prompt to be sure she is not required to write on more than one text.)

6. What are the biggest questions I still have about this essay?

I’m worried that I’m not going to have enough to say and the paper won’t be long enough. Maybe I should consider including info about the world in general at that time, specifically about how girls lived, to understand what it was like for someone like Ophelia? Can I do that? I guess I need to ask.

7. What do I still need to do?

I just realized I have not even started working on citing the sources. I need to do this ASAP! Ask Professor Brown how to cite that article I found online!

CUBING

Some writers use a cubing tool to help generate ideas. “Cubing” means considering your topic from six different perspectives. Just as a cubed dice has six sides, a cubed brainstorming session will result in six “sides” or approaches to your topic. Do your best to write about all six “sides” of the cube, but keep in mind that not every side will apply to all topics or assignments.

Take out a sheet of paper, or open a blank document on your computer. Take three to five minutes to write about your topic from each of the following six perspectives (give each perspective three to five minutes):

1. COMPARE AND CONTRAST IT. In what way(s) are the subject, texts, or ideas similar and/or different?

2. ASSOCIATE IT. Connect the material to something you care about, know, or understand.

3. ANALYZE IT. Break down the prompt into parts, and address the meaning of each part in relation to the whole.

4. APPLY IT. Apply to the “real” world; in other words, “So what? Who cares?”

5. DESCRIBE IT. How does the subject look, sound, taste, smell, or feel?

6. ARGUE FOR AND AGAINST IT. What are the pros and cons? Who agrees with you or not, and why?

If your writing prompt actually contains one of the above terms, you may want to spend additional time on that “side.”

When you finish with all six sides, you will see which side seems most interesting or relevant. If one particular side was easy for you to consider and write about, this may be the perspective to focus on in your essay.

Below you will find the first four sides of Robin’s cubing on her topic of comparing the depictions of fathers and daughters in The Taming of the Shrew and Ten Things I Hate About You.

1. COMPARE AND CONTRAST

SAME: The plot is basically the same: daughters having trouble with their fathers being too overbearing and having too much say in their lives. The father characters are sort of the same, but they’re also different. Both dads want the best for their daughters, but Baptista seems more distant and also more interested in marrying them off than really making sure they get the best guy. The girls’ characters are pretty much the same. Bianca is like the perfect one who is “daddy’s little girl,” and Kat is the outcast who is seen as a troublemaker, but Mr. Stratford actually tells Kat at the end of the movie that he’s proud of her for being like she is, for being so tough and for not just settling for any guy who comes along. I guess that would be a difference because Baptista never says anything like that to Katherina. He seems to want to change her so he can be rid of her; he doesn’t accept her for who she is.

DIFFERENT: Mr. Stratford is much more protective of his daughters than Baptista is. Baptista seems like he is more interested in getting rid of them than in protecting them. I mean, he lets some guy he met five minutes before marry his oldest daughter! He doesn’t even know Petruchio, but he lets him talk to Katherina alone and then even agrees to let him marry her! Mr. Stratford won’t even let a guy take his girls to prom without meeting them first. I guess that’s another difference: The girls in the play are dealing with marriage whereas the girls in the movie are dealing with dating.

2. ASSOCIATE

I really related to the film more than the play because of the way the dad is so protective and won’t let Bianca date unless her sister does. I was the younger sister, too, and my dad often punished me for my sister’s decisions, which is how Bianca feels her dad treats her. I liked how the film made Bianca more relatable and explained her behavior. She can’t understand why her dad won’t let her make her own decisions and trust her judgment. Just because Kat does or doesn’t do something doesn’t mean Bianca will. Not sure what else to say or how I could tie that into my essay...

3. ANALYZE

This is the hard part for me. What parts should I look at? I guess I could look at how the girls’ relationship with their father (is this the part?) relates to the play or film itself (is this the whole?) Without the conflict between the father and the daughters, there really wouldn’t be a plot. The whole story revolves around the dads’ interference in their lives, so maybe the meaning of the whole story is related to that, the power the father has over his daughter’s lives. Is Shakespeare saying that’s a good thing? Is the film saying that? I hope not! I think it’s terrible. It’s like the dads decide their fate or something.

4. APPLY

I guess the “real world” application would be why we still care about this story hundreds of years later. Does the remake show us anything about how much we’ve changed over time? Maybe I could talk about how the dad in the film seems to have a better relationship with the daughters and seems to see them as people instead of stuff to sell off or be rid of. Maybe this is why he has a better relationship with them.

IDEA-GENERATION STRATEGIES AT A GLANCE

Although each of these strategies can help generate many different types of information depending on the writer and the assignment, the chart below indicates which strategies have proven the most helpful for eliciting the specific type of information indicated.

|

WHAT YOU NEED |

TRY THESE STRATEGIES |

|

Organization |

Idea Map, Outline, Venn Diagram |

|

Relationships Between Ideas |

Idea Map or Cluster, Venn Diagram, T-chart, Cubing |

|

Compare/Contrast |

Freewriting, T-chart, Venn Diagram |

|

Pro/Con |

Freewriting, T-chart, Outline, Cubing |

|

Ideas in General |

All Freewriting and Brainstorming Strategies, especially Free Freewriting |

|

Evidence |

Q & A, Reporters’ Questions, Cubing |

BEYOND COLLEGE

Many jobs require employees to be able to compare and contrast different policies, ideas, candidates, or products, and your future employer may also expect you to be able to brainstorm and outline new ideas on the spot. The Venn diagram and the T-chart in particular are considered invaluable tools for idea generation in business, education, government, and economics.

HOW TO USE YOUR BRAINSTORMING AND FREEWRITING

After you brainstorm and freewrite sessions, you may face a difficult question: How can you turn the ideas on the page or screen into an actual essay? The answer depends on the writer.

Some writers begin composing the draft immediately after brainstorming and/or freewriting; they simply look at the page and see the structure of their essay, so they’re ready to write. Other writers need more organization first, so they prefer to create a coding system, an outline, or another brainstorming session.

Regardless of your process, remember that you do not have to write the draft in a certain order; you don’t need to write the introduction first, then the body paragraphs, and then the conclusion. If while brainstorming you get a flash of genius regarding the conclusion, go ahead and write it. Don’t get bogged down with the order in which you “should” write. You can always go back and write the introduction later.

Don’t forget that even after you begin writing your essay, if you get stuck, you can always go back to brainstorming and freewriting. Keep working on it and trying different techniques until you find one that works for you.

You will find on the following pages strategies writers use to turn idea-generation sessions into workable material for essays. However, don’t feel as though you must complete these strategies. If you feel ready to compose the essay, then by all means move on to chapter 2. If you would like more help in organizing and structuring the ideas you have generated, then try one or both of the strategies to follow.

GROUPING AND LABELING

In this strategy, the writer labels each sentence or idea within her freewriting. This activity will help you see what elements of your paper (Points, Illustrations, or Explanations, also known as “P.I.E.”) have taken form and which have not. For more information on “P.I.E.,” see chapter 3. To use this strategy, follow these steps:

1. Read through your brainstorming or freewriting. Don’t label anything yet; just read.

2. If you wrote your ideas by hand, get out a colored pen or pencil (use a different color than the one you used for brainstorming or freewriting); if you typed your ideas, open a new blank document.

3. Read through your ideas again. If you wrote out your ideas by hand, use the colored pen or pencil to circle each idea or piece of information you believe you can use in your paper. If you used the computer, copy and paste the “usable” information into the new document. You may want to begin by considering all of your ideas as “usable”; you can always cross them out or simply move them to a “trash heap” page later. Regardless of your decision, don’t delete any of your ideas! Sometimes an idea or detail may not seem important, but you later realize you need it after all. If you wrote by hand, put the paper in a folder and hold onto it until you’ve completely finished the assignment. If you composed on the computer, use a “trash” page or document and name the file “Paper 1 Trash Page” or something similar. (Remember, you never know when these seemingly irrelevant ideas will later prove important or helpful to you.)

4. Go through and label each idea or piece of information so that you know its potential function in your paper.

• Label major points by writing or typing a large P next to them.

• Label evidence and examples by writing or typing a large I next to them.

• Label information that explains points and evidence with a large E.

5. Count how many points you have, and then highlight each one and write or type it in large print onto a blank page or screen. Leave plenty of room underneath it, and space each point far enough away from the others to distinguish each one.

6. Decide where each illustration will go, and write or type that location underneath the appropriate point in smaller print or font. Do the same with all explanations.

Review your work; you should have several points listed, with evidence and explanations listed under each point. These will form the basis of your essay’s paragraphs. If you only had one or two points, that’s okay. More ideas will come to you as you write.

In the below example, Jenny has completed steps 1 through 4 of the Grouping/Labeling strategy, which she applied to her compare/contrast analysis of Peter Griffin and Homer Simpson.

Notice that her brainstorming has generated several points (P) she can explore, and with all the illustrations (I) she has listed, she probably will not have trouble defending these points. However, notice how few explanation (E) statements she has. Assuming she has correctly labeled her ideas, this exercise has revealed what elements of her paper she has begun writing already (P and I) and which she has not yet developed (E). She also noted a few items she was unsure about (those labeled with a question mark); as she writes the essay, she can decide whether this information is useful to her.

|

PETER GRIFFIN (FAMILY GUY) |

HOMER SIMPSON (THE SIMPSONS) |

|

· Idiot (?) · Fat (?) · Lazy (?) · Incompetent at job, goes through several jobs (I) · Spends a lot of time at the bar (I) · He is mean to his daughter Meg and seems like he could not care less about her. She is the family joke, and he encourages this (P). There are lots of episodes where he makes fun of her and calls her names (I). · He is mostly uninterested in the other kids unless they can do something for him (P); he spends more time with his friends than with his kids (I). · Peter treats Lois horribly; he is a terrible husband (P). I don’t know if he ever actually cheated, but I think he would if he had the chance. Need to check on this (I). He and his friends check out other women all the time, which shows he sees marriage as a joke and doesn’t take it seriously like Homer does (E). |

· Idiot (?) · Fat (?) · Lazy(?) · Incompetent at job, but keeps the same job for most of the show(I) · Spends a lot of time at Moe’s (I). (Does he spend as much time as Peter does? I need to check on that.) · He is nice to Lisa (most of the time, lol), encourages her a lot, and loves her; he wants the best for her (I). He sees her as the best thing he ever did and is a good father to her (P). · He fights a lot with Bart but has a definite connection and bond with him (P). There are lots of episodes about them doing things together (I). · I think Homer spends more time with his family than with his friends, definitely more than Peter spends with his family (P). · Homer is a good husband overall (P). He does not cheat on Marge, even when he has the chance. He and his friends don’t really talk about and look at other women; do they (I)? Need to check … |

This example shows steps 5 and 6 of Jenny’s Grouping/Labeling work. She has first listed her “P” statements and underneath copied her “I” and “E” statements. Notice she remained uncertain about the usefulness of some of her “I” statements, but she included them anyway. She can always delete this information later if she decides it proves irrelevant.

PETER

· He is mean to his daughter Meg and seems like he could not care less about her. She is the family joke, and he encourages this (P).

· Incompetent at job, goes through several jobs (I). (Not sure this “I” goes with this “P.”)

· There are lots of episodes where he makes fun of her and calls her names (I).

· He is mostly uninterested in the other kids unless they can do something for him (P).

· He spends more time with his friends than with his kids (I).

· Peter treats Lois horribly; he is a terrible husband. (P)

· I don’t know if he ever actually cheated, but I think he would if he had the chance. Need to check on this (I).

· He and his friends check out other women all the time, which shows he sees marriage as a joke and doesn’t take it seriously like Homer does (E).

HOMER

· He sees Lisa as the best thing he ever did and is a good father to her (P).

· Incompetent at job, but keeps the same job for most of the show (I). (Not sure this “I” goes with this “P.”)

· Spends a lot of time at Moe’s (I). (Does he spend as much time as Peter does? I need to check on that.) (Not sure this “I” goes with this “P.”)

· He is nice to Lisa (most of the time, lol), encourages her a lot, and loves her; he wants the best for her (I).

· He fights a lot with Bart but has a definite connection and bond with him (P).

· There are lots of episodes about them doing things together (I).

· I think Homer spends more time with his family than with his friends, definitely more than Peter spends with his family (P).

· Homer is a good husband overall (P).

· Homer does not cheat on Marge, even when he has the chance. He and his friends don’t really talk about and look at other women; do they (I)? Need to check …

GETTING IT OUT: 7 STEPS TO DRAFTING

Now that you have generated ideas and worked to organize them, you can begin drafting your essay. Keep in mind these tips as you draft.

1. YOU DON’T HAVE TO WRITE YOUR ESSAY “IN ORDER.” Don’t feel you must rigidly stick to writing the introduction first, then the body paragraphs, and then the conclusion. Some writers compose their introduction last and their conclusion first, and others write the body paragraphs first and compose the introduction and conclusion paragraphs last. Experiment with writing different parts of the essay in different orders, and then do what works best for you.

2. WRITE YOUR FIRST DRAFT AS RAPIDLY AS YOU CAN. In writing the first draft of your essay, try to get as many ideas down on paper (or on the computer screen) as quickly as you can. Don’t worry about spelling, grammar, punctuation, repetition, or irrelevance—just write. Don’t pause to delete or cross anything out. You will have time to edit later; for now, let your ideas flow without any censorship.

3. COMPOSE THE ESSAY USING MULTIPLE METHODS: TYPE AND HANDWRITE IT. Each writer has a different relationship to his computer versus the classic pen-and-paper method. Even if you always type your essay from start to finish, try handwriting some of it or vice versa. Switching your method will switch your thinking and thus lead to new and different ideas and strategies. If you try switching methods and it doesn’t work for you, you don’t have to keep doing it—but at least give it a try.

4. DON’T LET A BLOCK IN ONE SECTION STOP THE ENTIRE ESSAY’S COMPOSITION. When you are writing your first draft, you will probably find that you don’t have all of the material you need for a finished essay. For example, you may know that you need more evidence to support your points but cannot think of any. If you experience a block in a particular section, simply write yourself a bracketed note that details what you need and then move on. For example, your note may look something like this: “[INSERT EXAMPLE HERE].” You can always add the evidence later, but for now you are free to move on to the next section or point.

5. WRITE IN TIMED—AND UNTIMED—BLOCKS. When composing, try writing without a time limit until you run out of ideas. Clear your schedule so you can sit as long as you need, and just allow the ideas to flow. The next time you write, do the reverse: Set a time period (ten minutes, for example), and write the entire time period without stopping. When the time limit expires, put the pen down and walk away.

6. TALK IT OUT. Discussing your ideas is one of the best strategies for composition. Most people do more talking than writing, so they feel more accustomed to explaining ideas aloud. If you begin to stutter or repeat yourself, it will probably be more obvious in speech than in writing. Plus, articulating your essay aloud forces you to clarify and succinctly convey your points and evidence. This strategy also helps you find new ways of wording and explaining your ideas. Whether you talk to your roommate, instructor, or even just yourself, talking about your work helps you become more direct about your current stance, and it often leads to newer, better ideas as well.

Ask the person you speak with to play devil’s advocate; in other words, encourage her to find holes in your logic and consider perspectives, rebuttals, or questions you may not have yet considered. Addressing other people’s criticisms and/or questions will strengthen and improve your thinking on the topic—and, of course, your writing on it.

7. KNOW WHEN TO WALK AWAY. Kenny Rogers was right. Knowing when to walk away is an invaluable skill, especially for a writer. You will almost certainly hit walls or blocks as you write your essays and other assignments in college, but if you learn when to keep going and when to walk away, you’ll save yourself much time and aggravation.

Keep going when you feel you are onto something, when you’re riding a wave of inspiration, or when you can feel it coming but it’s not yet arrived. Sometimes the best ideas or inspirations come in the midst of working through a block.

Walk away when you can’t seem to get it done no matter how hard you try. If you work and work and work and still aren’t making any progress, it’s time to walk away. Ironically, sometimes the best strategy for working on an essay is not working on it. So give yourself a break. Go outside. Get a cup of coffee. Go out with your friends. Watch an episode of your favorite show, take a nap, or read a book—just do what it takes to give yourself space from your work for a while (don’t stay away too long!). When you feel ready, go back and try again, and hopefully your muse will show up and inspire you. I have found she always does—if you’re patient …

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

Imagine you work for an environmental company, and your supervisor has asked you to create a presentation in which you must convince the audience that wind energy is a wise investment for their community. Just like in your academic papers, for your presentation you must achieve the following:

· Present a clear and convincing thesis

· Gain the audience’s attention and trust so you can introduce the topic

· Outline your points, cite evidence to support them, and explain why the audience should agree with your perspective

· Leave the audience impressed with your final conclusions so that you persuade them to agree with your perspective and take the action you recommend

Remember that when you write essays for your college classes, you are essentially presenting your ideas, and if you apply the drafting tips you learned above, you will be able to create work that will impress and persuade your audience.