Essential Writing Skills for College and Beyond (2014)

Part II. COMPOSING YOUR ESSAY

Chapter 2. Your Ideas

The college essay requires students to develop their own ideas and also to address the ideas of other scholars. In this chapter we will focus on developing your ideas, but keep in mind that you will need to address the perspectives of other scholars as well. If you write with this overall understanding in mind, you will avoid making one or both of the two major mistakes beginning writers typically make in their college writing assignments:

1. TOO MUCH OF “THEIR IDEAS”: Excessive summary of other scholars’ work and ideas

2. TOO MUCH OF “YOUR IDEAS”: Complete omission of other scholars’ work and ideas

Neither of these approaches will lead to a high score on your essay. Remember, successful academic writing requires the inclusion of both your ideas and other scholars’ ideas.

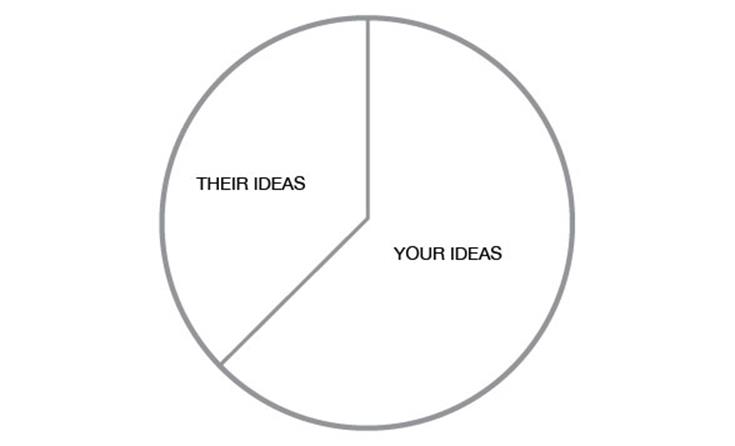

Exactly how much of “you” and how much of “them” should gain representation in your essay? Unfortunately, scholars do not universally agree upon a specific percentage or ratio of “their” ideas to “yours.” This ratio will likely depend on the topic, the discipline, and even the professor. However, a good rule of thumb does exist: Unless your instructor states otherwise, your essay should consist primarily of your ideas, with other scholars’ ideas cited as a foundation and support for your own.

If you imagine your entire essay as a pie chart, think of your ideas as being the larger “piece.”

Because your ideas are so important, we will begin by addressing how to develop and polish them. Once you have a firm grasp of your own perspective, you’ll be well equipped to address and evaluate other scholars’ perspectives. If your instructor requires you to first complete research and then develop your ideas, or if you simply prefer this method, skip to chapter 4.

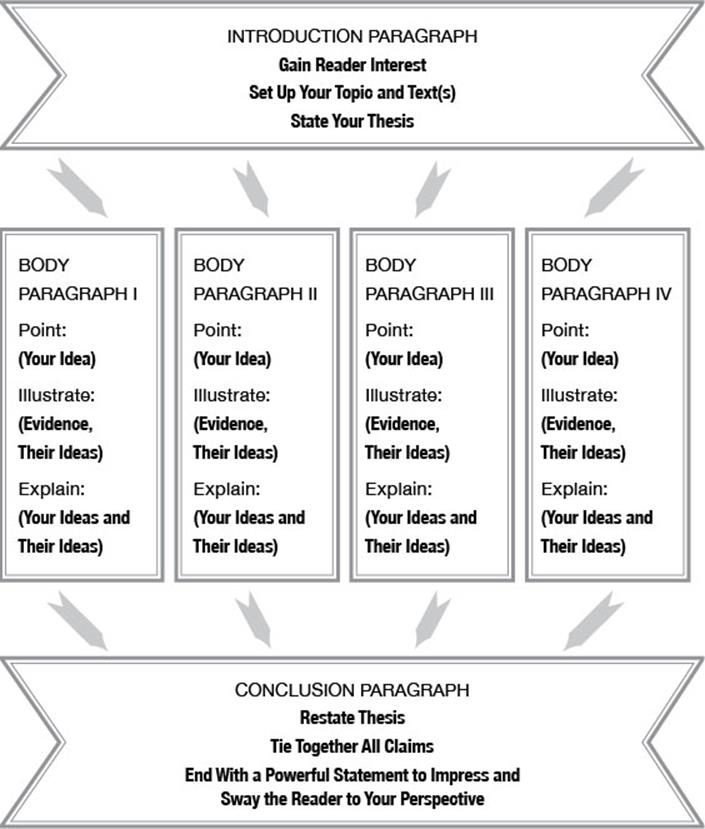

VISUALIZING THE ESSAY

Following this paragraph, you will find a visual breakdown of the essay so you can envision its overarching structure. This is not to suggest that you must have four paragraphs in your essays; you do not. The diagram is just a model designed to give you an overall idea of the essay’s structure. As you advance into upper-division classes, you will write longer papers with many more paragraphs, but luckily this same structure applies, regardless of the essay’s length.

NARROWING DOWN YOUR IDEAS

After you’ve completed brainstorming and/or freewriting, you will hopefully have some good ideas to mold into an essay. (If not, continue with the freewriting or brainstorming process.)

Now you must ensure the ideas you came up with are specific enough that you can write a thesis statement; in other words, the ideas should be so defined that readers can immediately determine exactly what your essay aims to discuss, prove, analyze, or examine.

PUT YOUR CARDS ON THE TABLE

When you present your point(s), be exact and defined in your language. In other words, put your cards on the table, so to speak. State exactly what you will attempt to prove in your essay. Avoid being vague or aloof in the attempt to inspire curiosity in the reader. This strategy may have worked in high school or middle school, but it will not impress academic readers. Professors do not see vagueness as an invitation to read more; they see it as a blaring neon sign that says the writer has no idea what he will discuss in the essay. Such vagueness will translate into a poor score.

Remember, academics do not sit with bated breath, excited to discover your ideas. Professors want the bottom line first and the proof and details later. If the bottom line is interesting, then they’ll examine your proof to make sure it’s solid. If the bottom line does not interest them, then they see no point in examining the evidence, and if they decide this is the case, it will probably translate into a failing score.

Think of your essay as akin to your hand in a poker game, and think of your thesis statement as the sentence that reveals that hand. Your thesis statement should answer this central question: What do you have in your hand?

Don’t bluff. Academics can spot a bluffer quicker than a dog can spot its favorite bone. (Remember, your professors read hundreds of essays each semester, not to mention they were once students themselves …). If you don’t have a good hand, keep working on it until you do.

Read Robin’s example statements below to see how she took vague, general ideas and molded them into specific, clearly defined ideas for her essay.

In 10 Things I Hate About You and The Taming of the Shrew, father/daughter relationships are depicted in both similar and different ways.

How well has Robin addressed the prompt? Can you discern what point each major body paragraph will address? If you think it’s hard to tell, you’re right. Robin doesn’t present a claim but instead states an obvious fact. She needs to outline the specifics of her analysis: How do the depictions differ, or do they—and why are these depictions significant?

Here, Robin narrows her topic.

In both 10 Things I Hate About You and The Taming of the Shrew, the father figures have excessive control over their daughter’s love lives; however, Mr. Stratford has much better intentions than Baptista does, which imparts an important understanding within both texts.

Robin now presents a claim statement with which she can argue, and she has further specified her argument. However, she still needs to be a bit more specific to ensure readers fully understand her thesis. For example, she needs to define “better intentions” and “an important understanding.” These phrases are still too vague to allow us to follow her argument.

Here, Robin narrows her topic further.

Both texts depict controlling father characters and show that the motivation behind this control determines the daughter’s ultimate fate. Baptista’s selfish motivation leads to a horrific ending for Kate, but Mr. Stratford’s benevolent motivation leads to a happy ending for Kat.

Robin has now better defined her ideas on the topic, and we can discern the overall structure of her essay:

· BODY PARAGRAPH 1: Comparison of each text’s “controlling father” characters

· BODY PARAGRAPH 2: Baptista’s motivation and its connection to Kate’s “horrific ending”

· BODY PARAGRAPH 3: Mr. Stratford’s motivation and its connection to Kat’s “happy ending”

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

Most of us have sat in boring presentations or endured long-winded writing in which the speaker or writer rambled on and on and on—for several sentences, paragraphs, or pages—before finally stumbling onto their main point. This type of communication won’t likely win you favor with your bosses, colleagues or benefactors. Therefore, it is crucial to learn how to narrow down your ideas so you can present them clearly and succinctly when given the opportunity.

In fact, many employers encourage or even require their employees to develop an “elevator speech” for their department, division, program, or product. The pitch is so named because it should last no longer than the average elevator ride (about one minute). It requires the speaker to succinctly and powerfully convey to others the most important points or attributes of what they do, make, sell, or offer—all in less than a minute.

Practice this skill of narrowing down your ideas now, and later you can impress your boss and clients with your verbal acuity.

THESIS STATEMENTS

The thesis statement is among the most important sentences in an academic essay; in fact, having a strong thesis is crucial to writing a strong essay.

The thesis statement asserts the essay’s main idea and purpose; the thesis immediately reveals to readers the essay’s organization and expresses concisely what, exactly, the writer will discuss and prove.

THE THREE LAWS OF THE THESIS STATEMENT

1. The thesis statement outlines the essay’s purpose and presents the essay’s argument.

2. The thesis statement is one declarative sentence that is clear, specific, and arguable.

3. The thesis statement’s argument matches the ideas presented within the body paragraphs.

THESIS STATEMENTS AT A GLANCE

THE THESIS STATEMENT SHOULD:

· Present an arguable claim

· Outline the essay’s structure

· Clearly connect to the topic and prompt of the assignment

· Appear as the last sentence of the introduction paragraph

· Contain a “how” and/or “why” element

· Interest and engage readers

THE THESIS STATEMENT SHOULD NOT:

· Merely present a question

· Contain vague, unclear phrasing such as many, some, very, really, kind of, a lot, there are, there is, certain way, today, today’s world, society, you, I, and so on (See the “Banned Words and Phrases” section in chapter 8 for an in-depth discussion on these words and phrases.)

· Force the reader to guess what the paper will prove or discuss

· Include confusing language

· Present a fact or definition

If you begin to compose the body of your essay and you do not yet know what your thesis is, don’t panic. The thesis statement will likely change and grow as you compose. Don’t be afraid to alter or even completely change your thesis to reflect your new ideas and body paragraphs. However, once you’ve determined your position, be sure your thesis statement reflects the arguments advanced in the body paragraphs.

EXAMPLES

Read Kim’s sample thesis statement below.

Different scholars see and interpret Ophelia’s death in many different ways, and in this essay, I am going to discuss these ways and why they are important for readers to understand.

This thesis statement is weak. It presents a vague answer that fails to outline either the argument or structure of the essay. It also tells us little about her perspective. What will Kim argue? What is her view of Ophelia’s death? As readers, we have no idea. It sounds as though Kim has no ideas of her own and is simply going to tell us about others’ ideas.

Instead of merely summarizing what others have written about Ophelia’s death, Kim should address what she believes and outline that interpretation for us.

Never write, “In this essay, I will ….” What is the point of announcing “In this essay”? Readers know the work is an essay; there is no need to say so. Nor do you need to make a declaration of “I will discuss ….” Readers understand that a writer will discuss information, so there is no need to announce this fact.

Don’t tell the reader you will discuss a topic; just discuss it. In other words, instead of talking about discussing the topic, actually discuss it. You can do this by deleting the phrase “In this essay, I will” and then stating your point. If you don’t yet have a point, reference the brainstorming and freewriting sessions completed earlier in the writing process.

For example, in her brainstorming session Kim wrote the following.

Maybe that’s what Shakespeare’s trying to say through Ophelia, that she is controlled by everyone around her and the only way she could gain power and control of her life was by ending it. Maybe her suicide shows that she felt the only way she could be free was in death.

This is an interesting idea and much more specific than “other scholars see her death in different ways.” This idea about control and its connection to her death could be developed further as an argument for the essay. For example, here is Kim’s first revision.

Ophelia kills herself because she is controlled and rejected by everyone around her.

The revised version shows improvement; the second half contains a claim. However, the phrase “everyone around her” is still too vague.

In the final revision, Kim rewrites this phrase to further specify.

By connecting Ophelia’s suicide both to Polonius’s control of her and Hamlet’s rejection of her, Hamlet illustrates the “rottenness” that young women like Ophelia experienced in Denmark: a dark confinement that could be escaped only through death.

Let’s look at a different example from Russell.

Anyone who argues restaurant workers’ salaries should not be raised is an idiot.

Russell’s thesis statement violates the bond between the reader and the writer because it offers an insult rather than a point. Never insult a group of people when attempting to persuade, for you can never truly know whether your reader is a part of the group you insulted. Attempting to hide behind insulting language rather than presenting facts and evidence will not impress or sway an academic audience.

Instead, Russell should present and set up his argument about why restaurant workers should earn higher wages. For this attempt, he rereads his freewriting and realizes that he feels these workers deserve higher salaries because of the value of their work to our society. He writes the following revision.

Restaurant workers deserve higher salaries because the work they do is important and affects us all.

This improved version of his thesis statement contains a claim with which we could argue. However, the sentence does not give us an idea of the essay’s structure, and the ideas presented are still too vague. He needs to elicit more ideas, so he tries the Reporters’ Questions brainstorming activity (see chapter 1) and writes out the following questions.

HOW? How does the work of restaurant workers “affect us all”?

WHY? Why, exactly, is the work they perform so important?

WHAT? What type of monetary increase am I proposing?

WHO? Who deserves the raise? Should all restaurant workers earn more money or only the upper-level restaurant managers? Only food servers and cooks?

SO WHAT? Why would anyone care about this issue, especially those who do not work in restaurants?

Russell’s final revision offers readers a clearly defined thesis statement with which we could reasonably argue. We can immediately tell what major points the paper will prove, and Russell has successfully presented us with an outline of the paper’s structure.

Restaurant servers, bartenders, and cooks deserve at least a 25 percent increase in their current hourly wage because they ensure the safety and quality of public food and drink in restaurants and they provide a valuable service to our society: They allow diners to relax and enjoy camaraderie with others through shared bonding over food and drink.

CHECKLIST: REVISING THESIS STATEMENTS

Writing a detailed thesis statement is by no means easy; it takes time, patience, and practice. Few people expect beginning baseball players to hit home runs each time they step up to bat, and similarly, few professors expect beginning students to write a perfect thesis statement. However, the more you practice, the better you will become at writing them—and this expertise will not only earn you higher scores, but it will save you time and frustration as your writing assignments become more complex.

If you worry your thesis might not achieve all that it should, use the following checklist to help you revise it.

· The thesis statement references key terms from the essay’s topic.

· The thesis statement outlines the essay’s claims and primary position(s) on the topic.

· The thesis statement is arguable; it is not a statement of fact (in other words, reasonable people could offer conflicting opinions on the ideas presented).

· The thesis statement contains no vague terminology, such as “lots of reasons,” “many similarities,” or “I will explain in this essay …” If so, replace these words with more specific terms. (For example, replace “lots of reasons” with the specific reasons you will discuss, and simply remove “I will.”)

· The thesis reflects the organization of the essay and gives the reader an overall trajectory of the paper.

· The thesis statement is the last sentence in the introduction paragraph.

· The arguments stated in the thesis match the actual arguments of the body paragraphs.