Essential Writing Skills for College and Beyond (2014)

Part II. COMPOSING YOUR ESSAY

Chapter 3. Breaking Down the Essay

COMPOSING THE BODY PARAGRAPHS: EASY AS P.I.E.

Most students have likely heard their English, art, or philosophy instructors say that there is no “right” or “wrong” interpretation in a persuasive or analytical essay. Students then wonder how instructors grade these papers if no “right” or “wrong” answers exist. The distinction in rhetorical analyses is not a matter of right or wrong but rather one of convincing versus unconvincing.

Building effective body paragraphs is absolutely crucial to writing a successful—convincing—argumentative essay.

A convincing, interesting body paragraph contains:

· A clear tie to the paper’s thesis and to the paper prompt

· Topic sentences that state clearly what the body paragraph will prove

· Specific textual evidence to support each claim

· Clear explanations that tie together the claim and evidence to support the thesis

Think of writing the paragraphs as being easy as P.I.E.

Point

Illustrate

Explain

Each body paragraph should clearly state the Point: the purpose or claim of the paragraph, i.e. what the paragraph will discuss and prove.

Each body paragraph should contain myriad Illustrations: examples, quotes, evidence, and proof that demonstrate, support, and illustrate the point.

The writer must then clearly and effectively Explain the significance of all examples, quotes, evidence, and proof to ensure readers understand the importance of each.

VISUALIZING THE BODY PARAGRAPHS

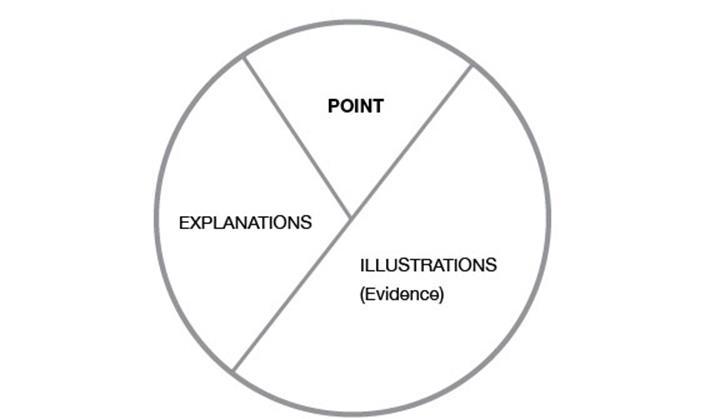

As you compose the body paragraphs, consider the proportions of the component “slices,” so to speak. How many sentences should be devoted to the point? To the illustrations? To the explanations? Different assignments and topics will differ in how many sentences each component will need. No set formula dictates, for example, that each body paragraph should have one point sentence with five illustration (evidence) statements and three explanation sentences. However, most of the body paragraph’s information should work to explain and defend the point.

Your point sentence(s) will take up the smallest portion, while the illustrations (evidence) and explanations will occupy most of each body paragraph’s space.

Let’s now take a closer look at the three elements of body paragraphs.

POINT

· The claim or position the paragraph seeks to prove

· Stated immediately in a topic sentence (usually the first or second sentence of the body paragraph)

· Clearly addresses and answers the prompt

· Only one per body paragraph

· All information in the body paragraph should clearly tie to this one major point

FACT VS. POINT

A fact is not arguable because we can prove it. For example, the sentence “Some corporations in the United States do not pay taxes,” is a fact, not a claim. We could check IRS or company tax records to verify this information. Use facts as evidence, not as points.

A point is a claim, an argument, or a statement of opinion. A point statement presents an idea with which we could argue. It is not a statement that can necessarily be proven as true or false but rather as having credibility or not.

For example, the statement “Corporations that do business with United States consumers must pay taxes into the U.S. economy,” presents a point. Not everyone would agree with this statement, and there is no way to prove it absolutely true or not.

CHECKLIST FOR “POINT”

· Each body paragraph contains a topic sentence that explicitly states the paragraph’s point.

· Each body paragraph remains focused on this one major point; all information in the paragraph relates to this point (either explains or proves the point).

· Each body paragraph’s point reflects the argument outlined in the thesis statement.

· The order of the body paragraphs matches the order listed in the thesis.

EXAMPLES

Read Kim’s first point statement. Does she present a claim?

Ophelia shows up to Gertrude’s castle acting “importunate” and “distracted,” singing songs and then saying “good night” four times right before readers learn she is dead.

This statement presents a fact, not a claim. We can verify in the text whether or not this writer presents an accurate overview of Ophelia’s final words and actions. Therefore, Kim has given herself nothing to argue. She needs to tell us the significance of this information; in other words, what is her point about Ophelia’s final actions and words?

Now consider Kim’s revision:

Ophelia’s cryptic final words clearly foreshadow her death and illustrate her plan to commit suicide.

The statement now presents a claim; readers could argue with this perspective. Now Kim must defend and explain the claim.

In the second example, another student, Russell presents his first point statement. Is it a claim or a fact?

Restaurant workers, such as servers and bartenders, are among the only workers within the entire workforce in the United States who have not been included in minimum-wage increases; in fact, their hourly wages have not been increased by federal law since 1991.

This statement also presents a fact, not a claim. We can verify with the Department of Labor that these particular workers’ hourly wages have not increased in the time span indicated. Although this statement might work well as an illustration for a claim, it is not itself a claim statement. So far, Russell has not stated an argument.

Consider his revision:

If restaurant diners in the United States want to maintain clean, safe, and relaxing facilities in which to dine, they must support a federal minimum-wage increase for the servers, cooks, and bartenders who handle their food and drink.

The statement now presents a claim; readers could argue with this perspective. Russell must now defend this claim with explanations and textual evidence to illustrate for readers why this increase in wage is so crucial and how this wage affects food quality and safety in restaurants as the statement indicates.

ILLUSTRATE

The “I” section of your body paragraphs provides your readers with evidence to support the essay’s thesis (your overall argument), so be sure to spend ample time ensuring you have strong, convincing, and relevant evidence to support each and every point.

Citing evidence often sounds like a difficult, tedious process to many students, but remember that your ultimate goal is simply to support your point. The “I” section explains to readers why they should consider your perspective as valid. In other words, write your illustrations to answer this question: Why should anyone believe your point?

What information counts as “illustration” in academia depends on the assignment and the instructor. Read your assignment carefully to see if the instructor outlined the specific types of evidence you must include (such as research study results, quotes from in-class texts or notes, or specific authors or types of references you must cite). If so, be sure to follow these instructions closely; if not, ask the professor what types of evidence you can include. A philosophy instructor may allow you to include personal experience as an “illustration” in your essay, but an English or history professor probably won’t.

Types of evidence to consider for your “I” section include:

· Quotes

· Examples

· Statistics

· Research findings

· Interviews

· Expert testimony or opinion

· Analogies

· Surveys

Remember to check with your instructor to ensure the evidence you cite is appropriate for the assignment. Once you determine the types of evidence to include, follow the three-step process outlined below:

1. SELECT THE ILLUSTRATIONS.

• Be highly selective. Include only quotes and information that support and illustrate your point. Do not quote just to quote.

• Cite only evidence from academic, scholarly sources (see chapter 4).

2. SET UP THE ILLUSTRATIONS.

• Don’t quote-bomb the reader. Set up and explain all quotes.

• Assume that readers don’t understand the quote’s importance; explain it.

3. CITE THE ILLUSTRATIONS.

• Always give proper credit to the texts you reference so you don’t risk plagiarism charges (see chapter 10 for more on plagiarism).

• Cite the information in your essay (in the paragraph) and at the end of your essay (in a Works Cited or References page).

QUOTING VS. PARAPHRASING

Many students struggle with understanding when to offer a direct quote from a text and when to simply paraphrase the author’s meaning. Understanding the difference can help you illustrate your points effectively.

A quote is a direct, exact, identical, word-for-word restatement of material from another text or source.

A paraphrase is an indirect (not exact, identical, or word-for-word) restatement of material from a source. It is a summary of the text written in your own words.

Direct quotes offer powerful illustrations to present to your readers, but be careful you do not overquote. Readers expect most of your work to be yours, not a mere regurgitation of someone else’s. Use quotations to build, support, and illustrate your point, but use them sparingly. Don’t bury your reader beneath a heap of quotations.

When You Should Quote

From a fictional text (such as a short story, play, or novel):

· Important or precise dialogue, thoughts, or stage directions

· The narrator or speaker’s specific commentary

From a nonfiction text (such as an essay, book, or journal article):

· Eloquent or impassioned language (such as expert testimony)

· Definitions or well-worded explanations

When You Should Paraphrase

From a fictional text:

· When referring to a specific event in a text

· When offering a summation of lengthy information, such as an entire passage or an overall synopsis of the plot or setting

From a nonfiction text:

· When the original information is too complex or lengthy to quote all of it

· When the exact language may not be appropriate or clear for your point(s)

CHECKLIST FOR “ILLUSTRATE”

· I can easily defend these quotes or paraphrases if challenged.

· The placement of the quotes or paraphrases makes logical and organizational sense.

· I cited each quote or paraphrase in the Works Cited page at the end of the essay.

EXAMPLES

Step 1: Select a Quote

Kim hopes to support her point that Ophelia’s final words foreshadow her suicide. Read her illustration choice below; do you think she effectively selected an illustration to support her point?

“I hope all will be well. We must be patient, but I cannot choose but weep to think they would lay him i’ the cold ground. My brother shall know of it. And so I thank you for your good counsel. Come, my coach! Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.”

Kim’s choice of quote is not as effective as it could be. Though she uses Ophelia’s precise language, which will offer strong support for her point, Kim does not need to use all of the quoted dialogue she cites. She should include only the specific portion of the dialogue that will illustrate her point. Unless she plans to address every word or phrase within the long quote, she needs to pare it down to only the essential elements she will discuss.

Consider Kim’s revision:

“Come, my coach! Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.”

Kim can now effectively address the shorter quote and explain why it proves her point.

Step 2: Set up the Illustration

Now that Kim has selected her illustration, she must set it up within her essay’s paragraph. She must lead readers to the quote so they are prepared for it and do not feel as though she quote-bombed them. A writer “quote-bombs” when she simply drops a quote into a paragraph and does not properly set it up or comment upon it. Quote bombs disorient readers and leave them feeling confused about the writer’s choice to switch from his own words to someone else’s without signaling this change.

Read Kim’s set-up sentences and quote inclusion below; see if you feel she has set up her illustration well.

Ophelia’s cryptic final words clearly foreshadow her death and illustrate her plan to commit suicide. Although some readers might be shocked when they read of Ophelia’s death, the text does prepare readers for it. Ophelia herself alludes to her suicide plan with the last words she utters in the play. She says, “Come, my coach! Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.”

Kim plans to use the selected quote to argue that it 1) foreshadows Ophelia’s death and 2) points to Ophelia’s allusion to her suicide plan. Therefore, it is important to set up these points before offering the quote. This information gives readers a better understanding of why she offers this quote and sets up her late discussion of why she finds it so significant.

Kim will still need to explain why she feels the quote illustrates her point, but this information falls under the “E” (Explain) portion of the paragraph, which we will discuss on the following pages.

Notice that Kim has not yet cited the quote. This information is crucial; she must offer a reference to show the source from which she retrieved the quote.

Step 3: Cite the Illustration

As you will learn in chapter 7, writers must cite sources in two ways:

· In text (parenthetical)

· Works Cited (or References) page

In this particular case, quoting from a Shakespearean play within the body of the text, Kim must cite the play’s abbreviation, act, scene, and lines.

She says, “Come, my coach! Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night!” (Ham IV.v.71-73).

Kim must also include a Works Cited page at the end of her essay; this page contains a listing of all references she included in her text. To view examples and learn more about citing sources, see chapter 7. For more detailed questions on how to cite specific text, consult the appropriate writing manual for your discipline (MLA, APA, or Chicago style). If you are unsure which manual you must use, ask your instructor or librarian.

EXPLAIN

· Tie together the Point and its Illustration.

· Ensure your body paragraph clearly answers the question “So what?” in relation to the prompt.

Never assume readers understand the importance of your illustrations. If you do make this assumption, you will risk two situations that could prove devastating to your scores:

1. Readers will misunderstand or misconstrue your meaning.

2. Readers will assume you do not know how to cite evidence, and thus they will discount you as a writer with sloppy work that cannot be trusted.

The explanation section of your essay addresses why you included the evidence presented and how it illustrates your point.

Use the following key explanation words to clarify these connections between your points and your evidence.

|

TO ADD |

Also, and, further, furthermore, too, moreover, in addition to |

|

TO GIVE AN EXAMPLE |

For example, for instance, consider as an example, to demonstrate, to illustrate, in this case |

|

TO COMPARE/CONTRAST |

Whereas, but, yet, conversely, as opposed to, rather, on the other hand, however, nevertheless, less, more, greater, worse, better, neither, nor, both, and, more likely, less likely, despite, in spite of |

|

TO PROVE |

In fact, because, for, since, clearly, thus, indeed, by, as, makes clear, illustrates, demonstrates, exhibits, makes evident |

|

TO SHOW EXCEPTION |

Although, though, yet, still, however, nevertheless, in spite of, despite |

|

TO CONNECT |

Thus, clearly, in fact, indeed, of course, specifically, in particular |

CHECKLIST FOR “EXPLAIN”

· The essay includes transition words that help cue readers to the connections between my ideas and my evidence.

· I fully explain the significance of each quote or paraphrase.

· I address and answer the question “So what?” in each paragraph so readers understand my ideas and their importance.

EXAMPLE

Consider Kim’s sample list below, containing the three P.I.E. elements.

(P): Ophelia’s cryptic final words clearly illustrate her plan to commit suicide.

(I): “Come, my coach! Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.”

(E): The “coach” is a reference to suicide.

Her repeating the phrase “good night” FOUR times shows readers she is planning to go away permanently, so her drowning was not an accident but a planned suicide.

She says “good night” rather than “good-bye” to foreshadow where she’s going.

Now read her entire paragraph to see how she put the three elements together. The “E” (Explanation) words are bolded so you can easily recognize and consider them.

Ophelia’s cryptic final words clearly foreshadow her death and illustrate her plan to commit suicide. Although some readers might be shocked when they read of Ophelia’s death, the text does prepare readers for it. Ophelia herself alludes to her suicide plan with the last words she utters in the play. She says, “Come, my coach! Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night” (IV.v.71-73). Her call for a “coach” exhibits Ophelia’s call for her own death; because she calls for it herself, she shows us she is planning it herself, clearly a planned suicide and not an accidental drowning. The “coach” is a metaphor for suicide; it is the vehicle she will use to get to her “good night,” in other words, her death. The phrase “good night” comes right after her calling for the coach to illustrate the connection between the coach and the “good night.” In fact, she repeats “good night” four times to demonstrate to readers that she is not leaving temporarily but permanently. Her specific phrasing matters, too; she says “good night” rather than “good-bye” to make evident that it is the night that she sees as good, so (like Hamlet in Act II) Ophelia’s words show that she sees death as a nice, peaceful place to go.

Kim has indeed followed the structure of P.I.E.; she has provided an argument, listed evidence, and tied this evidence to her point.

INTRODUCTION AND CONCLUSION PARAGRAPHS

Strong essays contain both introduction and conclusion paragraphs. Effective opening and concluding paragraphs create the credibility and interest academic writers expect. Just as the body of the essay will certainly influence graders, so, too, will the introduction and conclusion paragraphs. Write these paragraphs well, and you will undoubtedly win points with your grader.

A STRONG, INVITING OPENING PARAGRAPH

When you browse for books in a bookstore, secondhand shop, or library, how do you decide whether to purchase or check out the book? Although different readers have different selection processes, most people decide whether they are interested in a book based on the first few paragraphs—or even the first few sentences or words of the book.

We often use this criterion for evaluating films and television shows, too; if a program does not gain our interest immediately, we change the channel or dismiss it as uninteresting and/or unworthy of our valuable time and attention. Remember this fact when writing your introduction.

You might think of the introduction paragraph as akin to the entrance of a home; it should invite readers to enter. An appealing introduction paragraph will set up and be indicative of the brilliant ideas present within the essay. If academic readers can’t understand your argument by the end of the first paragraph, they won’t want to read any further, so work hard to ensure you gain your reader’s interest with your opening words. This is not easy to do, but spending time on your introduction will prove a smart and worthwhile investment—especially at the beginning of the semester. First impressions are hard to overcome, so associate your name and work with quality from the very beginning, and this association will likely stay with you for the rest of the semester.

AN IMPRESSIVE CLOSING

The conclusion paragraph influences readers’ perceptions of the entire essay, especially when you are writing for grades. The final statement(s) of your paper will likely be the last one(s) the grader reads before assigning the essay a grade, so you will want these statements to impress the reader and convince him of the value and merit of your work. If the entire essay demonstrates a well-polished, interesting, and informative discussion but the conclusion paragraph proves sloppy, lazy, and/or incomplete, readers will walk away from the work feeling disappointed or disoriented, and such feelings are detrimental to the writer and her grade. Be sure to tie up all loose ends and connect each of your major ideas to give the reader the big picture of your topic and perspective.

It might help you to consider your essay as a puzzle that you—the writer—put together for the reader to view. The conclusion paragraph represents the last piece of that puzzle, and without this crucial piece, your reader will not be able to fully see the picture or scene you’ve created with your essay. The conclusion allows you to tie together each of the points from your body paragraph and explain in detail the larger “So what?” of your essay and the perspective it offers.

After reading the conclusion paragraph, the reader should be able to step back from your essay and see its picture. Be sure to remind the reader of each of the key pieces of the “puzzle” in the conclusion paragraph so she feels all of the important pieces are intact, all the gaps filled.

WHAT IS THE FORMULA FOR THE INTRODUCTION AND CONCLUSION PARAGRAPHS?

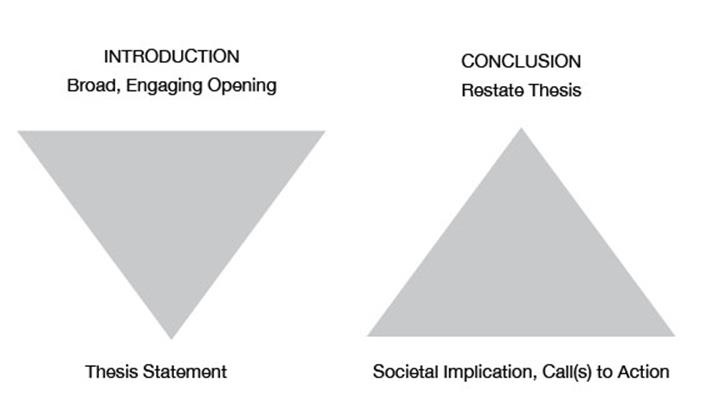

There is no set formula for “correctly” writing either the introduction or the conclusion paragraph. However, you can think of both paragraphs as having shapes like a triangle. The introduction begins with broad information and then slowly narrows down the topic until it reaches a point. The point represents the most specific sentence in the introduction-your thesis. The conclusion paragraph does the reverse: It begins with the specific information argued in your essay and then broadens to include societal implications and calls to action.

On the following pages, we will explore both introduction and conclusion paragraphs in more detail.

INTRODUCTION PARAGRAPHS

Introduction paragraphs serve several functions:

· Set the essay’s tone

· Pique reader interest

· Establish the essay’s topic and its importance to readers

· State the essay’s thesis clearly and concisely

Strong introduction paragraphs engage the reader and make evident the paper’s topic and trajectory. However, achieving this clarity and interest is not an easy feat. So, how do you write an effective opening paragraph? Often the essay’s first statement will make or break your introduction, so always choose your first sentence carefully. You can do so by following one or more of these opening strategies:

· Ask a thought-provoking question.

· Offer a shocking or unbelievable fact.

· Cite an interesting, provocative quote.

· Present a problem.

· Describe a compelling image.

· Provide a definition.

All of these strategies can work well in an essay, but they certainly do not guarantee an effective opening. The key to creating a compelling first sentence is simple: Ensure its relevance to your topic and ideas, and do not be afraid to point out this relevance to readers.

Quotes, questions, definitions, or statistics provide great openings for essays, but remember to always explain their significance. Answer the question, “Why have I included this information?” but don’t assume your readers understand why. Tell them. For example, citing an interesting quote from Darwin, Shakespeare, Einstein, or another famous thinker may seem impressive, but if that quote bears no clear relation to your topic, readers will immediately be confused or annoyed—but not impressed. Ensure that you clearly tie any information you offer directly to your topic.

Never offer readers a dictionary definition, whether in the introduction paragraph or anywhere within an essay, without commentary or explanation. Always follow up on definitions; otherwise, your work will seem lazy and elementary. Any student can slap a word’s definition into his essay, and in fact this method has been so misused that many instructors have banned it. Only include a definition if you find it interesting, compelling, or lacking. Then explicitly address this interest and/or lack.

EXAMPLE

Consider Jenny’s sample introduction paragraph comparing and contrasting the depictions of Homer and Peter as husbands/fathers in their respective shows.

Is The Simpsons or Family Guy a greater television program? Lots of critics have put these shows down for as long as they’ve been on the air. Both Peter and Homer are inadequate as leaders and providers for their families, but Homer is overall a good and caring husband and father, whereas Peter is a selfish and uncaring one.

As it stands, this introduction paragraph would unfortunately fail to impress an academic audience. I’ve outlined its specific strengths and weaknesses below.

“Is The Simpsons or Family Guy a greater television program?”

YES: The writer opens with a question and immediately points to the texts she will examine.

NO: The opening question confuses readers and muddies the topic. Asking the reader his or her opinion about the greatness (or lack thereof) of these programs seems irrelevant to the topic of comparing and contrasting the characters’ depictions. Instead, Jenny should introduce the importance of these characters, specifically within their roles as husbands and fathers.

“Lots of critics have put these shows down as long as they’ve been on the air.”

YES: It might be interesting to address the critical commentary of the programs.

NO: Raising the issue of critical commentary only works if Jenny ties this commentary to her topic. What is the connection between the critical reception of the program and the depictions of the husband/father characters? Jenny should also formalize her tone here; the language she uses is a bit too informal for an academic audience. (For example, she should spell out the contraction they’veand rephrase “lots of critics” and “put these shows down.”).

“Both Peter and Homer are inadequate as leaders and providers for their families, but Homer is overall a good and caring husband and father, whereas Peter is a selfish and uncaring one.”

YES: This statement, presumably the thesis, addresses the prompt and presents an interesting claim with which readers could argue.

NO: Jenny’s jarring jump to the thesis from a vague statement about critical commentary will confuse readers; she should set up the texts and characters to lead the reader to her thesis.

CONCLUSION PARAGRAPHS

Conclusion paragraphs give writers one last chance to convey the importance of their argument to readers (and, of course, to convince graders that the essay deserves a high score). Conclusions do not merely restate the thesis, and most professors detest the phrase “In conclusion...”.

When writing a conclusion paragraph, consider this central question: How does your essay help readers to better understand the topic?

The tasks your conclusion fulfills will vary according to your subject, audience, and objectives; generally, though, conclusions fulfill a rhetorical purpose—in other words, they persuade your readers to do something: to take action on an issue, to change a policy, to make an observation, or to understand or see a topic differently. You can achieve this by following one or more of the closing strategies listed here:

· Offer a stronger, more emphatic version of the thesis.

· Tie together all claims and evidence to illustrate the validity of your thesis.

· Close with a thought-provoking question to spur readers to think further on the topic.

· Cite an interesting, provocative quote.

· Point out the areas within the topic that need further investigation.

· Present a solution to the problem discussed in the essay.

As with introduction paragraphs, these concluding strategies only work well if they are relevant to your essay as a whole.

Set up your final statement(s), especially quotes and questions; you will not have further space to explain them, and you do not want your reader to walk away from the essay confused. Make sure to be specific in calls to action so readers will know exactly which actions you recommend.

You shouldn’t assume readers will understand the importance of the quote or question offered in your conclusion. Be careful not to oversimplify a large and complex issue or problem or introduce new points or material.

EXAMPLE

Consider Russell’s sample conclusion paragraph on the topic of wage structures in the contemporary United States:

Nobody wants to work hard all day on his feet, dealing with loud and rude customers and then not make any money. How can we expect quality food and service from these people for only $8 per hour, including tips? This wage amounts to barely $.75 above the minimum wage, while their high and mighty bosses get millions in bonuses! Sure, bosses should make more than their workers, but not this much more. It is imperative that we all get involved and do what we can to make sure the servers and bartenders who handle our food and drink receive a respectful living wage for the work they do.

As it stands, this concluding paragraph would unfortunately fail to impress an academic audience. I’ve outlined the conclusion’s strengths and weaknesses below.

“Nobody wants to work hard all day on his feet …”

YES: Russell attempts to restate an important point stated within the essay.

NO: The restatement of the point must be more direct. If the point is that high-quality workers will leave the restaurant industry for work that garners more respect and higher wages, then Russell should say so. Also, he needs to formalize the language and avoid generalizations (such as “nobody wants”).

“How can we expect quality food and service from these people …”

YES: This sentence raises an interesting question and reminds readers of important evidence stated in the essay (the specific wages of these workers).

NO: Again, Russell should formalize the language; the reference to restaurant workers as “these people” seems insulting. If his goal is to humanize these workers so readers will empathize with them, he must use more inclusive language.

“This wage amounts to barely $.75 above the minimum wage …”

YES: These sentences remind the reader of points addressed in the essay.

NO: Again, Russell must formalize his tone and specify the language. The point that “bosses should make more” remains undefined. How much more does Russell advocate? How much is too much? Also, he should avoid the name-calling (“high and mighty bosses”) and tie this statement to the thesis. How or why does this enormous gap between the boss and the workers’ salaries threaten diners’ enjoyment and safety in restaurants?

“It is imperative that we all get involved and do what we can …”

YES: This sentence is a call to action.

NO: This call to action is vague and thus ineffective. What, exactly, can readers do about this issue? Should they boycott restaurants? If so, which ones? Perhaps they should write their state or national senators to raise the state minimum wage for tipped employees. Russell should offer specific courses of action for this strategy to achieve its effect.

INTRODUCTION AND CONCLUSION WRAP-UP

· DON’T FEEL OBLIGATED TO WRITE THE INTRODUCTION PARAGRAPH FIRST AND THE CONCLUSION PARAGRAPH LAST. Many writers work on their conclusion long before they finish the paper, and some writers compose the introduction last.

· WRITING A STRONG INTRODUCTION PARAGRAPH FREES YOU TO USE THE SPACE WITHIN THE BODY PARAGRAPHS TO DEFEND AND EXPLAIN YOUR ARGUMENT. Without a strong introduction, writers must use the body paragraphs to set up the argument, leaving little space for proving and explaining it. This mistake often costs the writer two letter grades.

· BUILDING AN ESSAY IS, IN MANY WAYS, LIKE CONSTRUCTING A BUILDING. Beginning with a shaky, insubstantial foundation in your introduction paragraph will lead to a flimsy, substandard building, and the builder (you, the writer) will have to deal with the headaches that accompany poor construction.

View as an investment the time and energy spent constructing a strong foundation in the introduction paragraph. Once you construct this foundation, you can then safely discuss and explore increasingly complex issues within the body paragraphs and remain confident that your work will stand up to any grader’s scrutiny.

Remember the four main purposes of introduction paragraphs:

· Set the essay’s tone.

· Pique reader interest.

· Establish the essay’s topic and its importance to readers.

· State the essay’s thesis clearly and concisely.

Remember the three main purposes of conclusion paragraphs:

· Restate the thesis to remind readers of the essay’s overall purpose.

· Tie together all the essay’s information to make it cohesive and coherent.

· End powerfully to illustrate the validity and importance of the essay’s perspective.

Use the following checklists to ensure your introduction and conclusion paragraphs fulfill their purposes.

INTRODUCTION CHECKLIST

· Includes an interesting, attention-getting opening statement

· Sets up the topic(s)

· Sets up the text(s)

· Leads the reader to the thesis statement

· States the thesis (the argument of the essay) as the last sentence

· Reassures the reader by addressing the following questions:

· What is this essay about?

· You’re not going to bore me, are you?

· Why would I or anyone care about reading your essay?

· Why should I believe you?

· What evidence will you present?

CONCLUSION CHECKLIST

· Restates the thesis

· Does not introduce new points or ideas

· Ties together all points and evidence to illustrate the credibility of the essay’s perspective

· Ends powerfully (offers a compelling image, question, quote, or call to action)

· Readers will gauge the successfulness of your essay based on their answers to the following questions about your essay overall. Use your conclusion to ensure they answer each question with a resounding yes.

· Did the writer actually discuss the topic set up in the introduction?

· Did the writer state the thesis and stick with it throughout the entire essay?

· Did the writer present compelling evidence to support the thesis?

· Can I clearly explain that point now after reading the essay?

· Did the writer get me to care about this topic and his perspective on it?