Mathematics, Substance and Surmise: Views on the Meaning and Ontology of Mathematics (2015)

Enumerated entities in public policy and governance

Helen Verran1

(1)

School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, 18 Newgrove Road, Healesville, Melbourne, VIC, 3777, Australia

Helen Verran

Email: hrv@unimelb.edu.au

Abstract

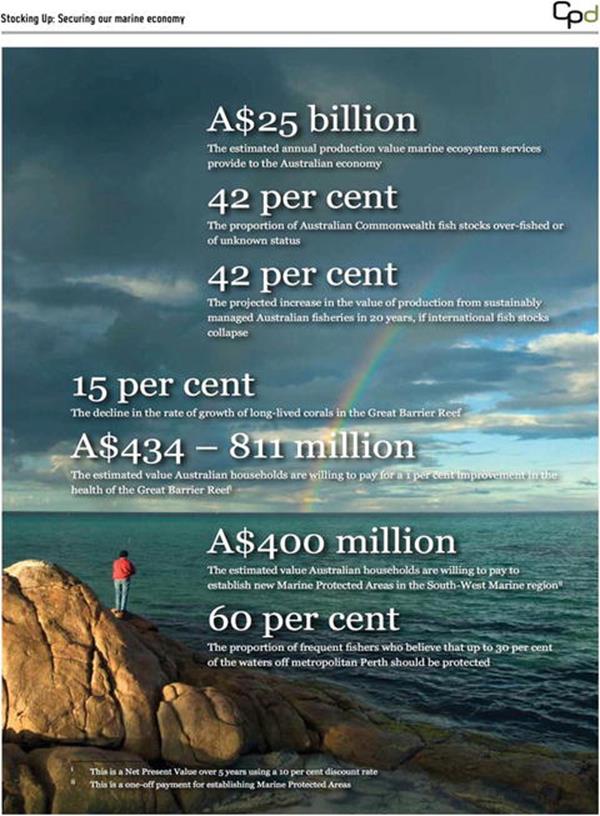

A poster promoting policy change in Australia’s fisheries, which features a list of seven numbers in its effort to persuade, serves as occasion to do ontology. A performativist analytic is mobilized to show the mutual entanglements of politics and epistemics within which these numbers, agential in policy, come to life. Three distinct types of entanglement are revealed. Numbers have different political valences, and mathematicians need to attend to these in order to act responsibly as mathematicians.

1 Introduction

The poster reproduced below appeared in a document published in 2011. The paper in which it appeared, “Stocking Up: Securing our marine economy,” proposed a radical new policy for Australia’s fisheries [7]. For me the poster serves as occasion to focus-up numbers as they feature in contemporary environmental policy and governance. The analogy here is focusing-up particular elements in a field in microscopy; settling on a particular focal length for one’s examination. The focal length I adopt, bringing numbers into clear view, is unusual in social and cultural analysis. But that focus is not the only way my commentary on the poster is unusual.

I work through a performativist analytic. And the first sign that mine is an unorthodox approach is that I will refer to enumerated entities rather than numbers from now on. From the point of view of my socio-cultural analysis, enumerated entities are very different from numbers, although a practitioner, a user, would certainly think that the difference, which I elaborate in my next section, rather exaggerated. For a user the terms number and enumerated entity can be interchangeable, but for a philosopher who wants to understand the mutual entanglements of epistemics and politics in contemporary life, a number is different than an enumerated entity.

A quick way to imagine my performativist approach to analysis is to remember John Dewey’s description of his examination of “The State” in his analogous attempt to understand how the concept of ‘the public’ is entangled in epistemics and politics [5]. “The moment we utter the words ‘The State,’ a score of intellectual ghosts rise up to obscure our vision,” he wrote. The same happens with ‘number.’ Dewey recommended avoiding a frontal approach, and instead opting for “a flank movement.” A frontal approach inevitably draws us “away from [the actualities] of human activity. It is better to start from the latter and see if we are not led thereby into an idea of something which will turn out to implicate the marks and signs which characterize political behavior. There is nothing novel in this method of approach,” he asserts. “But very much depends on what we select from which to start… We must start from acts which are performed…” Accordingly, I consider the ordinary, everyday routines, the collective acts, by which enumerated entities come to life, routines which nevertheless entail metaphysical commitments. In doing this I am undertaking ontology. I argue that enacted in this way and not that, enumerated entities have particular constitutions; they are ‘done’ in collective actions with machines and bodies as well as in collective actions with words and graphemes (like written numerals). Commitments, enacted as part of those collective actions, to there being ‘particular somethings’ which justify the doing of those routines, add up to metaphysical commitments. Unearthing those commitments is ontology.

I am bringing the particular origins and character of the political aspects of enumerated entities into focus. Such characteristics are embedded in enumerated entities as they come into being with particular epistemic capacities. As Dewey notes of his enquiry, there is nothing new revealed here. I adumbrate the everyday routines in which the partialities lie (both in the sense of being implicated in certain interests and hence not impartial, and in being of limited salience and referring to specific aspects of the world), and thus show politicization of enumerated entities. In doing so, I suspect many readers will think ‘So what? That’s just ordinary.’ Yes and that is the point. I am focusing up the political responsibilities that go along with being ‘a knowledge worker’—a scientist or a mathematician. The rather unusual ‘focal length’ and framing of my study reveal that the work of scientists and mathematicians, contrary to popular understandings which proposes such work as ‘objective,’ actually bears “the marks and signs which characterize political behaviour,” to use Dewey’s words. Scientists and mathematicians of course are expected to behave responsibly when it comes to epistemic practices. But recognizing enumerated entities as political and their knowledge making as inevitably partial (both not disinterested and limited), implies that they have further responsibilities too. In my opinion, these responsibilities too, should be remembered by scientists and mathematicians as they participate in policy work.

2 How is an enumerated entity different than a number?

In doing ontology in a performativist analytic, Dewey’s image of what he set out to do, is a good start in imagining how my analytic is constituted as a very different sort of framing. As Dewey has it, a performative analytic looks side-on at the conventional account of numbers. An enumerated entity as known in a performative social science analytic, is different from a number as understood by most ordinary modern number users. While the latter belongs in a stable state of being, the former exists in the dynamic of emergence realness.

Here’s a definition of enumerated entities as I understand them. Enumerated entities as objects known in a performative analytic, are particular relational beings; they are events or happenings in some actual present here and now. Importantly there are quite strict conditions under which enumerated entities come into existence as relational entities in our worlds. Part of the wonder of enumeration is that sets of very specific practices can indeed happen just as exactly as they need to, again and again, as repetitions. Sets of routine practices must be collectively, and more or less precisely, enacted in order for an enumerated entity to come to life. So, in looking ‘inside,’ what most people would simply call numbers (and probably not imagine as having an inside), I elaborate the every day techniques by which they come to life. Like all entities in a performative analytic such as I mobilize here, the several kinds of enumerated entities I consider in asking about the family of enumerated entities displayed on the poster, are relational particulars named by singular terms.

On one side, the roots of the performative analytic approach lie with a conceptual turn in the ordinary language philosophy of Wittgenstein [19] and Ryle [13] as mobilized in the subsequent ‘speech act theory’ of Austin [1] and Searle [14]. These philosophies of language evaded the dead-hand of a posited external logical framework with which to fix the proper meaning of linguistic terms. Later in the century, working from the material world, the ‘things end’ of meaning making so to speak, the actor network theory of Latour, Callon and Law [10] mobilizing a version of French post structuralism offered what might be called ‘materiality act theory.’ As in the earlier linguistic shift, this approach too circumvented the dead-end of positing some external ‘real physical structure’ with which to fix meanings things have. Linking these two distinct ‘turns’ to performativity by making an argument for word using, including in predication and designation, as a form of embodiment [17] I constituted a means for recognizing the performativity of the conceptual across the full range of meaning making with words and things. This analytic frame of performative material-semiotics (to give it a formal name) is particularly generative when it comes to ‘looking inside’ numbers, which are first and foremost entanglements of linguistic terms (either as spoken words or inscribed graphemes) and things; entanglements of words and stuff.

Here’s an example of particular metaphysical commitments being ‘wound-in’ as enumerated entities come to life in a state institution, and the sort of thing we can see when we ‘look inside numbers.’ Mathematicians in the state weather bureau are required to offer predictions of future temperatures and future rainfall. They use models and data sets they know to be reliable, and which have actually been constituted as ‘clots’ of differing materializing routines, and differing linguistic gestures (written or spoken). In the mathematicians’ careful work, knowledge, or justified belief about the future is generated. The state’s epistemic grasp is extended to the future although of course the future is unknowable. At the core of this explanation of this vast collective endeavor is a metaphysical commitment: the future will resemble the past. This commitment is embedded as those enumerated entities that are temperature and rainfall predictions are constituted. But now pay attention to the enumerated entities that make up the data—lists of actual past temperature and rainfall readings produced in the extensive and enduring institutional work of the state weather bureau, data which are fed into models. We all know that these enumerated entities are different to the predictions. There is a quite different set of metaphysical commitments buried in those assiduously assembled values, just as they are produced in quite differing routines than the predictions. The commitment here is to the past as real, an actual then and there that happened, with rainfall and temperature having these specific values. So the enumerated entities which are predictions of temperature and rainfall, have different constitutions than the readings of past temperature and rainfall, and of course the predictions fold in the readings and are more complicated; each step introduces particular metaphysical commitments. As a socio-cultural analytic, performativity takes quite seriously the minutiae of the actual generation of enumerated entities, details which applied mathematicians are quick to cast aside.

3 The Poster Displays Three Types of Enumerated Entities

Most of the enumerated entities listed on the poster exemplify the type generated in a style of reasoning that more or less simultaneously emerged in seventeenth century European experimental enumeration [16], in mercantile life [11], and in governance practices of the early modern state [15]. This empiricist type of enumerated entity ‘clots’ in an elaborate set of categorical shifts [16]. In making up a stabilized and self-authenticating style of reasoning [9] emergent in the epistemic shifts of the innovative laboratory practices of the likes of Galileo, these empiricist enumerated entities evaded the domain of the dominant idealist enumerated entities which came to life in the scholastic institutions of the established Christian church [6]. These empiricist enumerated entities, coming to life in the political and epistemic maelstrom of seventeenth Europe, are politico-epistemological units. And they became the mainstay of governance and policy practices in organizations doing administration in early modern states and in early modern capitalism [11].

What empiricist enumerated entities offer to experimentation, commerce, and state governance is a way of managing the sorites, or heap paradox with enough certainty. The sorites paradox arises in vague predicates like heap, pile, or territory. If one starts with a pile of rice and begins taking grains away, when does it stop being a pile? Or if one starts as a king with a territory and keeps giving bits of it away to supporters to defray costs, when does one stop being king ruling the vague territory of a kingdom, and become just another landowner with a specific area of land? Managing this paradox in an actual circumstance is a contingent matter radically dependent on context.

Empiricist enumerated entities, as they came to be in the so-called scientific revolution are a way of rendering the vague whole of the empirical world, of what is capitalized, or of what is governed (which in the case of the early modern state was territories and populations), into specific units in and through which experimental proof, capitalization, and governance, respectively, can proceed (natural and social facts). Rendering a vague whole into specific units to effect the last of these, governance, is necessarily a form of state politics. In the early modern state as much as the contemporary state, the empiricist enumerated entity establishes an interested order as the order of government—the so-called natural order in this case, which inevitably distributes goods and bads differentially amongst the peoples governed. Empiricist enumerated entities offer a means for doing distributive politics through entities which offer a flawless nonpolitical appearance as epistemic units. These enumerated entities embed propositions about an actual (although past) world, and proclaim the epistemic soundness of the policy they are adduced to support.

This poster offers evidence that enumerated entities of the type which first emerged in governance practices of early modern collective life still do that work managing and stabilizing the vague whole of what is governed, infusing the process with an epistemic seemliness. It shows also that several further forms of enumerated entity have emerged over the past several hundred years expanding possibilities of managing and stabilizing in governance through enumerated entities. Two of the numerical values displayed on the poster are types that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. One emerged out of statistical reasoning as turned to modeling, and a felt need to seem to extend the epistemic reach of the state into the future [9]. In the process of their constitution these (statistical) enumerated entities enfold particular empiricist enumerated entities. In part this elaborate enfolding has been enabled by the exponential increase in processing power brought about by digital technology. While recognizable as rhetoric in that they embed propositions about a future that is in principle unknowable, these entities are persuasive as back up for the enumerated entities and like the entities from which they are derived, epistemically salient for policy and governance.

The other type of enumerated entity we see on the poster arose as a modification in late twentieth century governance practices in state organizations, as they shifted the focus of their administrative practices away from biophysical and social matters (territories and populations) to having economic infrastructure as what it is that they govern. In a profound ontological shift, a new vague whole—a financialized economic infrastructure, became as the object of government, as economizing, a style of reasoning previously confined to economics, came to life as the primary means of operationalizing governance practices of the state, at the end of the twentieth century. In part this occurred through the activism of the ‘new public administration’ social movement with its commitment to “accountingization” [12], but also in association with the enhanced operationalizing capacity that digital technologies offer. The workings of these two relatively recent forms of enumerated entities (statistical and economistic) in policy and governance, builds on the self-authenticating capacities of empiricist enumerated entities. In different ways they each offer further means for managing the sorites paradox in rendering the vague whole of what is governed into the specific units in and through which governance proceeds. The further enfolding, embedding as it does further metaphysical commitments, embeds further partialities, further politicization.

4 The Poster’s Empiricist, Statistical, and Economistic Enumerated Entities

In this section I attend to three of the enumerated entities listed on the poster in detail, speculating on the actual activities in which they came to life, discerning metaphysical commitments embedded in them, and hence, what I call their political valence. This section elaborates the nitty-gritty work of doing ontology in a performative analytic. The first enumerated entity I consider in detail is of the empiricist type—a natural fact; then a statistical enumerated entity, and next an economistic enumerated entity. Before I begin this detailing of the everyday I remind you that I am drawing attention to things ‘everybody’ knows and which most of us have learned to ignore. As you find yourself getting impatient I ask you to also recall that in doing their epistemic work these enumerated entities are agential—they are ‘empiricising,’ ‘staticising,’ and ‘economising.’ Once they begin to circulate in collective life enumerated entities have effects—they begin to change our worlds, at a minimum this occurs by directing our attentions to some things and not others, although some would claim that they have other sorts of capacities too. These enumerated entities are politically agential.

If one had lived through the savagery of Europe’s seventeenth century, I can imagine that finding oneself sharing one’s world with an empiricizing enumerated entity, might come as something of a relief, as indeed I discovered during the eight years I lived in Nigeria. Being politically agential is not necessarily a bad characteristic in an enumerated entity. But it is bad politically if we fail to recognize that and how such entities are politically active. And while the staticizing style of the language of the weather forecast might irritate many, the style of reasoning is made clear, the nature of the claim is explicit. Those who heed (or fail to heed) the enumerated entity embedded in a weather forecast must accept that it is they who make the decision in accord with it, and they bear the responsibility. But what of economistic/economizing enumerated entities, which unlike staticizing enumerated entities carry no instructions on how they are to be engaged with? What are the responsibilities come along with advocating governance practices through these entities? This is not the place to pursue that question. But my hope is, that such questioning emerges from what follows.

i. An Empiricist Enumerated Entity

The type of enumerated entity we are concerned with here presents truth claims about a specific aspect of the immediate past of Australian nature or Australian society:

· 42 per cent. The proportion of Australian Commonwealth fish stocks over-fished or of unknown status;

· 15 per cent. The decline in the rate of growth of long-lived corals in the Great Barrier reef;

· A$434–811 million. The estimated value Australian households are willing to pay for a 1 % improvement in the health of the Great Barrier Reef;

· A$400 million. The estimated value Australian households are willing to pay to establish new marine protected areas in the South-West Marine Region;

· 60 per cent. The proportion of frequent fishers who believe that up to 30 per cent of the waters off metropolitan Perth should be protected.

Making claims about ‘a then and there’ that once was ‘a present’ in which actual humans undertook specific sets of enumerating practices, in some cases these entities claim a precise value for a property of nature, and in others they claim a precise value for an attribute of society. In the history of the emergence of enumerated entities, it was nature, subject to the interrogations of the early experimentalists that first yielded empiricist enumerated entities. In part because of the success of this style of reasoning, society emerged as nature’s other, and it became possible to articulate social empiricist enumerated entities.

Here, in excavating what is inside such enumerated entities, I focus on ‘15 percent. The decline in the rate of growth of long-lived corals in the Great Barrier Reef’ as an enumerated fact of the natural world. In attending to the banal routines in which this natural empiricist enumerated entity came to life I will revisit a paper “Declining Coral Calcification on the Great Barrier Reef” published in the prestigious natural science journal Science in 2009 which the policy paper cites as the origin of the enumerated entity. We are looking for the metaphysical commitments, the ‘particular somethings’ which justify the collective doing of various routines and arrangements embedded in this entity.

Fifteen per cent is a way of expressing the fraction 15/100, which in turn is a simplification of the ratio of two values arithmetically calculated from three hundred and twenty eight actual measurements on coral colonies. Examination of the skeletal records embedded in some actual corals which grew at particular places in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, and were collected and stored in an archive in an Australian scientific institution, showed that they grew at an average rate of 1.43 cm per year between 1900 and 1970, but only at 1.24 cm per year between 1990 and 2005 [3]. Growth slowed by 0.19 cm per year, which might be expressed as the fraction (0.19/1.24) or 15 per cent which, represents the value of the decline in the growth rate of long-lived coral.

This ‘15 per cent’ is a truth claim, it is an index of a situation understood as having existed ‘out-there.’ It precisely values a characteristic of the natural world. The decline in the rate of growth of long-lived corals in the Great Barrier Reef’ has been put together through the doing of many precise actions on the part of many people.

We investigated annual calcification rates derived from samples from 328 colonies of massive Porites corals [held in the Coral Core Archive of the Australian Institute of Marine Science] from 69 reefs ranging from coastal to oceanic locations and covering most of the >2000-km length of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR, latitude 11.5° to 23° south…) in Australia. [3]

Imagine the justifications that lie behind the institutional resources that have been assembled and which are drawn on in contriving this entity: the instruments (from extremely complicated and complex—X-ray machines and GPS devices, to simple—hammers and boats), the work of sun burned bodies of scientists swimming down to chop pieces off coral colonies, and of the disciplined fingers of technicians who prepare specimens, and so on. Speculatively retrieving the human actions we recognize what a vast set of relations this enumerated entity is, albeit a modest little enumerated entity. And, this statement of ‘what we did’ expresses a huge and well-subscribed presupposition: there is a found natural order ‘out there’ (in the Great Barrier Reef and other places). Depending on one’s particular science, this general commitment to ‘the natural order’ cashes out in a specific set of commitments which in this case would go something like ‘in the found natural order long lived corals grow at a particular rate depending on their conditions of growth.’ In turning the vague general nature, a metaphysical commitment to one of reality’s far reaching categories, into a specific valuation scientists undertake complicated sets of measuring practices and come up with formal values.

The 1572–2001 data showed that calcification increased in the 10 colonies from ∼1.62 g cm−2 year−1 before 1700, to ∼1.76 g cm–2 year–1 in ∼1850, after which it remained relatively constant, before a decline from ∼1960. [3]

Why have I adumbrated all this? I want to reveal the partial nature of this enumerated entity. Here’s an example of its partiality. Many of those who use, love, care for, and participate in owing the Great Barrier Reef as an Australian National Reserve are (usually heedlessly) committed to there being a found natural order. But one group of Australians is not so committed. As well as being owned by the Australian State, the territory that is Great Barrier Reef is, according to the Australian High Court, also owned by two rather distinct groups of Indigenous Australians. It is recognized in Australian law that those Indigenous territories are not constituted as a natural order, as territory of the modern Australian state is. An enumerated entity that mobilizes that (modern) order is, in Australian political life, inevitably partial. Of course most members of the Indigenous groups, Australian citizens who co-own the Great Barrier Reef with the Australian state, recognize the usefulness of such an enumerated entity and in a spirit of epistemic neighborliness are content enough to have it inhabit their world, and in some cases protect it. Those Australians are making a political decision there. And so is the Australian state, and Australian citizens in general, in choosing to work through empiricist enumerated entities, although few would be able to recognize that. Enumerated entities, in being partially constituted participate in the distribution of goods and bads; they enact a particular sort of environmental justice.

ii. A Statistical Enumerated Entity

The second entity from the poster that I consider is the sort of enumerated entity that is currently causing much puzzlement amongst philosophers of science [8]. ‘Forty two per cent. The projected increase in the value of production from sustainably managed Australian fisheries in 20 years, if international fish stocks collapse,’ or 42/100 is, like that entity I have just considered, arithmetically speaking, a ratio of two values. The denominator A$2.20 billion per year has been assiduously assembled in one of the vast counting and measuring exercises that go towards constituting Australia’s national accounts. It is the total of value of four classes of Australian fish products.

The numerator has quite different origins. This value emerged not through counting and measuring by specific people in specific places at specific times, in generating empiricist enumerations that embed commitment to there being a vague nature, and a vague general entity ‘society’ in which ‘the economy’ can be found—all metaphysical commitments, but through calculation by a computer. To generate the prediction that the total value of Australia’s fish products in 2030 would be A$3.11 billion per year, a carefully devised computer programme, plied with rich streams of data, only some of which is derived from actual measurements, enfolded the A$2.20 billion per year value in a complicated set of calculative processes.

The difference between the actual value of the recent past (derived in actual counting and measuring actions) and the foreshadowed value of a carefully imagined future, would amount to an increase of A$0.91 billion per year. We can thus render the computed increase as a ratio: 0.91/2.20, which is more felicitously rendered as 42/100, or forty two per cent. Whereas A$2.20 billion per year (the denominator), indexing a collection of actual fishery products, an accumulation of the value of all fishery products landed each day in all Australian fishing ports for the year 2010, makes a claim about an actual situation, A$3.11 billion in 2030, and hence A$0.91 billion per year, cannot be such a claim, and so neither is 42 per cent, since 2030 has not yet happened. A$2.20 billion and A$3.11 billion purport to index the value of the fish products landed by Australian fishers in 2010 and which will be landed in 2030, respectively. They present as the same sorts of enumerated entity, and allow a seemingly trustworthy claim: we can expect, in certain circumstances, an increase of forty two per cent in the value of four national fisheries products. But even the cursory examination I have just made reveals there is a profound distinction between these two values. The distinction concerns the metaphysical commitments embedded in these two enumerated entities.

The particular program which generated the denominator of this ratio is called IMPACT (International Model for Policy Analysis of Agricultural Commodities and Trade) developed and maintained in the International Food Policy Research Institute in Washington DC. Among the categories included in the algorithms used to generate this value were the previously mentioned four classes of fish products, differentiated as captured or farmed, and including two categories of animal feedstuffs made from fishery products. Embedded in this numerator are values very like the denominator A$2.20 billion per year [7].

The denominator A$2.20 billion reports the past. It is a representation contrived in an elaborate set of institutional routines which start with actual people, perhaps wearing gumboots, weighing boxes of fish of one sort or another, and writing figures down in columns on a sheet attached to a clipboard, or perhaps in a few places, entering values into a computer tablet, that must be protected from splashes and fish scales. By contrast, A$3.11 billion is connected to such material routines only very weakly, and only to the extent that the values generated in such routines are incorporated into data sets to be manipulated by computer models. The computers in which A$3.11 comes to life need no protection from the wetness associated with actual fish and fishers. Similarly the institutional and literary routines in which this enumerated entity is generated are very different to those that give life to those like A$2.20 billion per year. No longer indexical (assiduously assembled in the past through actual people quantifying actual stuff), it becomes an icon where category and value are elided, in which there is no distinction to be made between category and value. It now performs as an element in a particular order. In being enfolded into what will become the numerator in the working of the computer program, the denominator begins to enact a ‘believed in’ order rather than the quantitative valuing of its previous indexical life.

The processes of the computing undertaken with this newly constituted enumerated entity then contributes to processes that are constructing new entities: icons that articulate the future. By setting these new entities, calculated as possibilities appearing in twenty years, in proportion with the indexical 2010 total, a purported partial expansion in value of Australian fish stocks can be calculated. After twenty years of oceanic ecological collapse (“an exogenous declining trend of 1 % annually,” as Delgado et al, describe it [4, p. 10]), this purported partial expansion will, it is said, increase substantially—by A$0.91 billion per year. This too, is an iconic entity where category and value are one and the same, and it has various parts and sub-parts, which could easily be read off from the computer output by an expert. This value collapses the present into a narrowly imagined future and are now pervasive in contemporary public life. They increasingly feature in politics and are crucial in generating policy. These enumerated entities now carry relations between economy and state. Indeed in the policy paper I exhibit here, A$0.91 billion per year, a (42 %) projected increase in the production value of fish, is crucial to the argument.

If anything will persuade politicians and the citizens they represent, it is this enumerated entity. It justifies taxpayers’ money being spent on establishing and running marine parks and protected areas. By justifying permission for one group to fish ‘over-there,’ but not the other, and disallowing them both from ‘here,’ the entity excuses differential control of various classes of economic agents, distinguished as they are by the socio-technical apparatus they mobilize.

This entity appears similar to the one I considered above, it seems to index, however, when we recognize it indexes a future, we see that it carries with it the commitment to a future that resembles the present, so it is a prediction, a prophecy, albeit with the performative features that go along with being a valid prediction within statistics. Nevertheless the metaphysical commitments embedded in its constitution have become obvious.

iii. An Economistic Enumerated Entity

The final enumerated entity I interrogate is ‘A$25 billion. The estimated annual production value marine ecosystem services provide to the Australian economy.’ It purports to value of the debt that, in the year 2011, Australian society accumulated in its utilizing of services provided by Australian nature—specifically its oceans. Fisheries and other marine economic activity of humans utilized these environmental services to generate wealth. Or to say this another way, environmental services which humans commandeered, and to which they added value through their activities, saw them indebted to nature to the extent of A$25 billion. What justifies the collective routines in which this value is calculated, is the metaphysical commitment to humans as debtors in some absolute sense, and to nature not as a biophysical entity but as economic infrastructure. A$25 billion is the debt owed to nature accumulated by Australians in 2011. We can classify this enumerated entity as economistic, a variety of statistical enumerated entities generated through statistical procedures using the so-called laws of economics. This is a particularly controversial example of the family of economistic enumerated entities in explicitly proclaiming itself as politically interested, while mimicking the form of empiricist enumerated entities which are popularly supposed to be non-political [2, 18]. This enumerated entity introduces politics as affect.

A$25 billion is a large value, so large that it seems to elude the comprehension of most numerate people. In addition, the claim that this names the very roughly estimated debt owed by the economy to nature, challenges our imaginations in a different way. Perhaps it is not surprising that the authors of the paper in which this enumerated entity is displayed make a fuss about it. Of the fifty-two pages of argument and evidence in this paper, nine are devoted solely to this value. Six are allocated to describing its conceptual design and three to justifying the actual value claimed. Of these nine pages more than half are devoted to showing that the value is really much, much larger than A$25 billion, but the authors have “been conservative” because in the time available it was not possible to quantify all the environmental services values provided by Australia’s oceans: for example, with respect to things like rivers and wetlands, it is not possible to determine where oceans begin and end; neither is it possible to determine how to separate Australian ocean ecosystem services from global ocean ecosystem services [7].

The first concerns that might occur to a careful reader of the paper in which this poster appeared are conceptual. In measuring environmental services, the authors claim to have identified a debt that Australia’s marine economy owes to nature—a certain percentage of the total use-value of Australia’s oceans. They claim that this debt the economy owes to nature, can be added to the credit generated in economic production—the exchange value of Australia’s ocean (A$44 billion). Adding A$25 billion (a vague estimate derived from modeling) to A$44 billion (a rather precise value derived from the national accounts), they come up with the statement that “Our oceans provide an estimated A$69 billion per year in value.” The enumerated entity mimics empiricist enumerated entities, in presenting this value as an index of an ‘out-there’ reality. Here a second concern arises. The physical object that is “our oceans,” which we are told gifts A$69 billion per year in value to Australia, is ineluctably vague, spatially indeterminable and existing for eternity. The authors’ claim that they had insufficient time to more precisely quantify the ecosystem services of Australia’s oceans is, in fact, made in bad faith. In actuality, the object is not quantifiable because it is not a physical object. It is no more quantifiable than the world’s unicorns. This enumerated entity has no epistemic salience to environmental policy.

This value A$25 billion, is presented as an index, proposed as ‘an indicator,’ when in actuality it is an icon; as an outcome of human collective activity the enumerated entity has a status that is analogous to a religious painting in a church which believers might kiss. In this enumerated entity, category and value are inseparable, they are one and the same. As a particular, it stands-in for an order, a set of beliefs, just as the icon of Christ on the Cross stands-in for an order of belief. Just as a pencil stroke in a geometry exercise book is the sole materiality of a geometric line, the sole materiality of this economistic enumerated entity is the nine pages in the report.

I suggest that it is useful to think of A$25 billion as words uttered with political intention. We should take the appearance of this value at the head of a list on the poster as performing like a shouted slogan [1]. In being uttered as a collective political act, a slogan that those at a demonstration might chant, “Australians owe their oceanic nature twenty-five billion dollars!” as they occupy Bondi Beach, aims to convince and/or enlighten as such chants do. This enumerated entity is emotive, and as rhetoric aims to convince. Here it is not truth that matters, rather it is persuasion. We can only ask about the felicity of this entity as rhetoric. Does it constitute good rhetoric to proclaim the approximate value of a debt to nature in hopes of enlightening, or in order to elicit recognition so that obligations might be imposed upon those who acknowledge its utterance? Is this entity persuasive? How to define a felicitous utterance here? The criteria for good and bad here lie in the esthetics of the art of politics and are not concerned with truth claims about the oceans or their fish. This enumerated entity explicitly relates to the conduct of environmental politics as affect.

5 Conclusion: Empiricizing/Statistitzing/Economizing Nature, and the Responsibilities of Scientists and Mathematicians

Excavating the human activities embedded in the enumerated entities listed on this poster (including metaphysical commitments embedded in those activities), reveals that the vague whole the contemporary state governs is biophysical territory and its population, and the economic infrastructure that supports present and future economic activity. Both these vague wholes are rendered governable as policy by being particularized as empirical, or alternatively, through statistical and modeling techniques. My argument has been that this rendering governable in the process of articulating policy amounts to a politics of distribution of goods and bads. The enumerated entities that enable this, are in so far as they are epistemically salient to policy, also political. In addition we saw that one of the enumerated entities listed on the displayed poster has no epistemic salience to environmental policy, announcing itself as explicitly politically interested through affect.

The question I pose to scientists and mathematicians in the light of this demonstration of the inevitableness of political nature of enumerated entities involved in government policy—in this case environmental policy, concerns their responsibilities. I am not referring here to their responsibilities as citizens who just happen to be scientists and mathematicians. On the contrary I am referring to their professional responsibilities as members of a knowledge community; their responsibilities as experts. Here I return to Dewey who in 1927, in the aftermath of the lethal demonstration provided by the First World War that science and technology were a challenge to democracy, was uncompromising in voicing his expectations of publically employed scientists and mathematicians [5]. He saw the professional responsibilities of scientists and mathematicians as of three types. First, he wrote, recognizing that human acts have consequences upon others implies that those who undertake acts—such as inventing techniques to calculate new sorts of enumerated entities, some examples of which we see displayed on this poster, have an obligation to consider how their acts as enumerators might involve untoward effects on those not directly involved in those acts. Second, as ‘officials,’ scientists and mathematicians bear the responsibility to actively to prosecute efforts ‘to control action [arising from their acts] so as to secure some consequences and avoid others.’ Third, recognizing the possibility of unforeseen, even perverse, effects of their acts as enumerators, as ‘officials’ scientists and mathematicians must recognize their responsibility to ‘look out for and take care of the interests affected.’ Unfortunately in the ninety years since Dewey wrote, the dangerous fantasy that enumeration somehow renders analytic entities as untainted with human interests, has showed no sign of diminishing its hold on the collective imaginations of mathematicians and scientists, who in consequence are no closer to considering how they might assume collective responsibility for the sorts of enumerated entities that find their way into public policy.

References

1.

J. L. Austin (1962). How to do things with words: The William James Lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955, J. O. Urmson & M. Sbisà eds. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

2.

N. Bockstael, A. M. Freeman, R. J. Kopp, P. R. Portney, V. K. Smith (2000) “On measuring Economic Values for Nature” Environmental Science and Technology 34 (2000), pp. 1384-1389.

3.

G. De’ath, J. Lough, and K. Fabricius (2009). “Declining Coral Calcification on the Great Barrier Reef,” Science 323: 116–119.

4.

C. Delgado, (2003). “Fish 2020 Supply and Demand in Changing Global Markets”, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington D. C.

5.

J. Dewey, The Public and its Problems (1927). Swallow Press, Athens: Ohio University Press, 1954

6.

Pierre Duhem (1996) Essays in the History and Philosophy of Science, Roger Ariew and Peter Barker, trans & ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

7.

L. Eadie and C. Hoisington, (2011). “Stocking Up: Securing our marine economy” http://cpd.org.au/2011/09/stocking-up/.

8.

R. Frigg and M. Hunter (eds) 2010. “Beyond Mimesis and Convention Representation in Art and Science”, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 262. Springer: Springer Science+Business Media.

9.

I. Hacking (1992). “Statistical Language, Statistical Truth, and Statistical Reason: The Self-Authentification of a Style of Scientific Reason” in The Social Dimensions of Science, Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press.

10.

J. Law (1999). “After ANT. Complexity, naming, and topology” in j. Law and J. Hassard, Actor Network Theory and After, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

11.

M. Poovey (1998). A History of the Modern Fact. Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences of Wealth and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

12.

M. Power and R. Laughlin, (1992). “Critical Theory and Accounting” in Alveson, N. & Willmott, H. (eds), Critical Management Studies, London: Sage.

13.

G. Ryle (1953). “Ordinary language.” The Philosophical Review, 62(2), 167–186. doi:10.2307/2182792CrossRef

14.

J. Searle (1969). Speech acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Law in Law and HassardCrossRef

15.

S. Shapin and S. Schaffer (1985) Leviathan and the Air Pump. Hobbes Boyle and the Experimental Life, Princeton: Princeton University Press

16.

I. Stengers, (2000). The Invention of Modern Science, trans. Daniel W. Smith, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

17.

H. R. Verran (2001). Science and an African Logic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

18.

H. R. Verran (2012). “Number” in Inventive Methods. The happening of the social, Lisa Adkins and Celia Lury (eds.) London: Routledge Books, pp. 110-124.

19.

L. Wittgenstein, (1953). Philosophical investigations. London: Blackwell.