5 Steps to a 5: AP Chemistry 2024 - Moore J.T., Langley R.H. 2023

STEP 4 Review the Knowledge You Need to Score High

13 Kinetics

IN THIS CHAPTER

In this chapter, the following AP topics are covered:

5.1 Reaction Rates

5.2 Introduction to Rate Law

5.3 Concentration Changes Over Time

5.4 Elementary Reactions

5.5 Collision Model

5.6 Reaction Energy Profile

5.7 Introduction to Reaction Mechanisms

5.8 Reaction Mechanism and Rate Law

5.9 Steady-State Approximation

5.10 Multistep Reaction Energy Profile

5.11 Catalysis

Summary: Thermodynamics often can be used to predict whether a reaction will occur spontaneously, but it gives very little information about the speed at which a reaction occurs. Kinetics is the study of the speed of reactions and is largely an experimental science. Some general qualitative ideas about reaction speed may be developed, but accurate quantitative relationships require experimental data to be collected.

For a chemical reaction to occur, there must be a collision between the reactant particles. That collision is necessary to transfer kinetic energy, to break reactant chemical bonds and form new bonds in the product. If the collision doesn’t transfer enough energy, no reaction will occur. And the collision must take place with the proper orientation at the correct place on the molecule, the reactive site.

Five factors affect the rates of a chemical reaction:

1. Nature of the reactants—Large, complex molecules tend to react more slowly than smaller ones because statistically there is a greater chance of collisions occurring in the wrong place on the molecule, that is, not at the reactive site.

2. The temperature—Temperature is a measure of the average kinetic energy of the molecules. The higher the temperature, the higher the kinetic energy and the greater the chance that enough energy will be transferred to cause the reaction. Also, the higher the temperature, the greater the number of collisions and the greater the chance of a collision at the reactive site.

3. The concentration of reactants—The higher the concentration of reactants, the greater the chance of collision and (normally) the greater the reaction rate. For gaseous reactants, the pressure is directly related to the concentration; the greater the pressure, the greater the reaction rate.

4. Physical state of reactants—When reactants are mixed in the same physical state, the reaction rates should be higher than if they are in different states, because there is a greater chance of collision. Also, gases and liquids tend to react faster than solids because of the increase in surface area. The more chance for collision, the faster the reaction rate.

5. Catalysts—A catalyst is a substance that speeds up the reaction rate and is (at least theoretically) recoverable at the end of the reaction in an unchanged form. Catalysts accomplish this by reducing the activation energy of the reaction. Activation energy is that minimum amount of energy that must be supplied to the reactants in order to initiate or start the reaction. Many times the activation energy is supplied by the kinetic energy of the reactants.

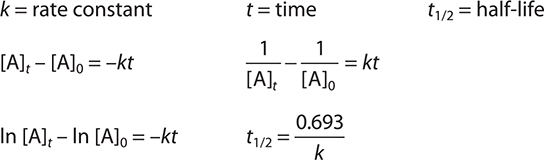

Keywords and Equations

How Reactions Occur—Collision Model

For two molecules to react, they must come into contact. However, simply coming into contact is not enough. Two conditions must be met for a collision to be effective. An effective collision occurs when the molecules collide with sufficient energy to react and with the proper orientation. The minimum energy necessary for an effective collision is the activation energy. This energy comes from the kinetic energy of the molecules, which have a Maxwell—Boltzmann distribution of energies. The “proper orientation” requires the reactive parts of the molecules coming into contact.

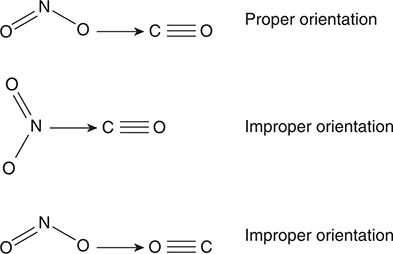

Let’s use the reaction NO2(g) + CO(g) → NO(g) + CO2(g) to illustrate what it means to have the proper orientation. Examples of the collision of the reactant molecules both with and without the proper orientation are illustrated in Figure 13.1. In the reaction, an oxygen atom is transferred from a nitrogen dioxide molecule to a carbon dioxide molecule. For this transfer to occur, one of the oxygen atoms from the NO2 must come into contact with the carbon atom of the CO. In the figure, only the first collision has the proper orientation (the O from NO2 coming in contact with the C of the CO). The second collision has the N from NO2 coming with the C of the CO. The last example in the figure has two oxygen atoms coming together. To make the first collision in the figure effective, the molecules would need to collide with sufficient kinetic energy to initiate the breaking of the nitrogen—oxygen bond and the formation of a carbon—oxygen bond.

Figure 13.1 Some examples of collisions between NO2(g) molecules and CO(g) molecules. The arrow indicates the relative motion of the NO2 molecule relative to the CO molecule.

The two requirements for an effective collision mean that only a small fraction of all collisions are effective.

Rates of Reaction

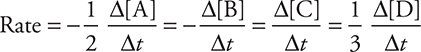

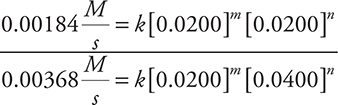

The rate (or speed) of reaction is related to the change in concentration of either a reactant or product with time. Consider the general reaction: 2A + B → C + 3D. As the reaction proceeds, the concentrations of reactants A and B will decrease, and the concentrations of products C and D will increase. Thus, the rate can be expressed in the following ways:

The first two expressions involving the reactants are negative because their concentrations will decrease with time (the reactants are disappearing). The square brackets represent moles per liter concentration (molarity). The deltas (Δ) indicate change (final — initial).

The rate of reaction decreases during the course of the reaction. The rate that is calculated above can be expressed as the average rate of reaction over a given time frame or, more commonly, as the initial reaction rate—the rate of reaction at the instant the reactants are first mixed.

The Rate Equation

The rate of reaction may depend upon reactant concentration, product concentration, and temperature. Cases in which the product concentration affects the rate of reaction are rare and are not covered on the AP Exam. Therefore, we will not address those situations. We will discuss temperature effects on the reaction later in this chapter. For the time being, let’s just consider those cases in which the reactant concentration may affect the speed of reaction. For the general reaction: a A + b B + . . . → c C + d D + . . . where the lowercase letters are the coefficients in the balanced chemical equation, the uppercase letters stand for the reactant, and product chemical species and initial rates are used, the rate equation (rate law) is written as:

![]()

It is important to remember that any similarity between the coefficients (a, b, etc.) and the exponents (m, n, etc.) is coincidental.

In this expression, k is the rate constant—a constant for each chemical reaction at a given temperature. The exponents m and n, called the orders of reaction, indicate what effect a change in concentration of that reactant species will have on the reaction rate. Say, for example, m = 1 and n = 2. That means that if the concentration of reactant A is doubled, then the rate will also double ([2]1 = 2), and if the concentration of reactant B is doubled, then the rate will increase fourfold ([2]2 = 4). We say that it is first order with respect to A and second order with respect to B. If the concentration of a reactant is doubled and that has no effect on the rate of reaction, then the reaction is zero order with respect to that reactant ([2]0 = 1). Many times the overall order of reaction is calculated; it is simply the sum of the individual coefficients, third order in this example. The rate equation would then be shown as:

Rate = k[A][B]2 (If an exponent is 1, it is generally not shown.)

It is important to realize that the rate law (the rate, the rate constant, and the orders of reaction) is determined experimentally. Do not use the balanced chemical equation to determine the rate law.

The rate of reaction may be measured in a variety of ways, including taking the slope of the concentration versus time plot for the reaction. Once the rate has been determined, the orders of reaction can be determined by conducting a series of reactions in which the reactant species concentrations are changed one at a time, and then mathematically determining the effect on the reaction rate. Once the orders of reaction have been determined, it is easy to calculate the rate constant.

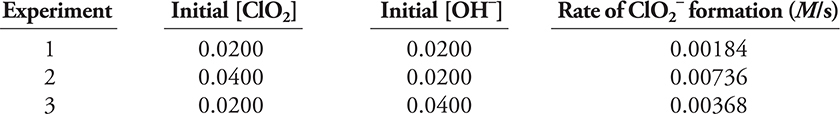

For example, consider the reaction:

![]()

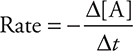

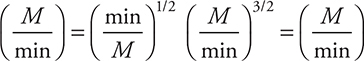

The following kinetics data were collected:

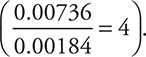

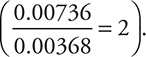

There are a couple of ways to interpret the data to generate the rate equation. If the numbers involved are simple (as above and on most tests, including the AP Exam), you can reason out the orders of reaction. You can see that in going from Experiment 1 to Experiment 2, the [ClO2] was doubled, [OH—] held constant, and the rate increased fourfold  . This means that the reaction is second order (22 = 4) with respect to ClO2. Comparing Experiments 1 and 3, you see that the [OH—] was doubled, [ClO2] was held constant, and the rate doubled

. This means that the reaction is second order (22 = 4) with respect to ClO2. Comparing Experiments 1 and 3, you see that the [OH—] was doubled, [ClO2] was held constant, and the rate doubled  . Therefore, the reaction is first order (21 = 2) with respect to OH— and the rate equation can be written as:

. Therefore, the reaction is first order (21 = 2) with respect to OH— and the rate equation can be written as:

Rate = k[ClO2]2[OH—]

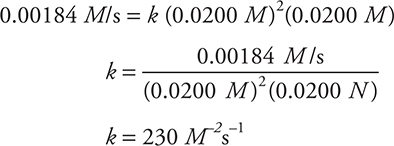

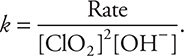

The rate constant can be determined by substituting the values of the concentrations of ClO2 and OH— from any of the experiments into the rate equation above and solving for k.

Using Experiment 1:

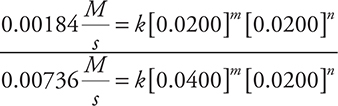

Sometimes because of the numbers’ complexity, you must set up the equations mathematically. The ratio of the rate expressions of two experiments will be used in determining the reaction orders. The equations will be chosen so that the concentration of only one reactant has changed while the others remain constant. In the example above, the ratio of Experiments 1 and 2 will be used to determine the effect of a change of the concentration of ClO2 on the rate, and then Experiments 1 and 3 will be used to determine the effect of O2. Experiments 2 and 3 cannot be used because both chemical species have changed concentration.

Remember: in choosing experiments to compare, choose two in which the concentration of only one reactant has changed while the others have remained constant.

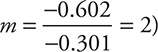

Compare Experiments 1 and 2:

Cancel the rate constants and the [0.0200]n and simplify:

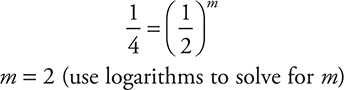

(To solve using logarithms begin with: [0.250 = 0.500m] and take the logs of both sides to get [log 0.250 = m log 0.500]; this leads to [—0.602 = m (—0.301)], and finally

Compare Experiments 1 and 3:

Cancel the rate constants, units, and the [0.0200]m and simplify:

Write the rate equation:

Rate = k[ClO2]2[OH—]

Again, the rate constant k could be determined by choosing any of the three experiments, substituting the concentrations, rate, and orders into the rate expression, and then solving for k.

Integrated Rate Laws

Thus far, only cases in which instantaneous data are used in the rate expression have been shown. These expressions allow us to answer questions concerning the speed of the reaction at a specific moment, but not questions about how long it might take to use up a certain reactant, etc. If changes in the concentration of reactants or products over time are taken into account, as in the integrated rate laws, these questions can be answered. Consider the following reaction:

![]()

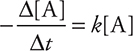

If this reaction is first order, then the rate of reaction can be expressed as the change in concentration of reactant A with time:

and as the rate law:

![]()

Setting these terms equal to each other gives:

and integrating over time gives:

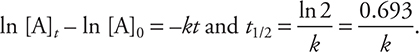

![]()

where “ln” is the natural logarithm, [A]0 is the concentration of reactant A at time = 0, and [A]t is the concentration of reactant A at some later time t. (Radioactive decay processes are the best examples of first-order kinetics.)

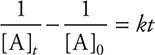

If the reaction is second order in A, then the following equation can be derived using the same procedure:

The only other integrated rate law that you may see on the AP Exam is a zero-order integrated rate law, which is:

![]()

Consider the following problem: carbon-14, 14C, decays through a first-order process to form nitrogen-14, 14N. The rate constant is 1.21 × 10—4 yr—1 at 25°C. How long will it take for the concentration of 14C to drop from 0.200 M to 0.190 M at 25°C?

Answer: 4.24 × 102 yr.

In this problem, k = 1.21 × 10—4 yr—1, [A]0 = 0.200 M, and [A]t = 0.190 M. You can simply insert the values and solve for t, or you first can rearrange the equation to give  . You will get the same answer in either case. If you get a negative answer, you interchanged [A]t and [A]0. A common mistake is to use the wrong integrated rate equation. The problem will always give you the information needed to determine whether the first-order or second-order equation or zero-order equation is required.

. You will get the same answer in either case. If you get a negative answer, you interchanged [A]t and [A]0. A common mistake is to use the wrong integrated rate equation. The problem will always give you the information needed to determine whether the first-order or second-order equation or zero-order equation is required.

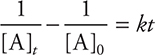

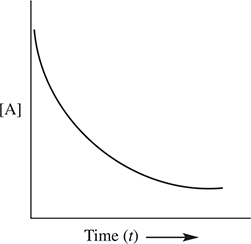

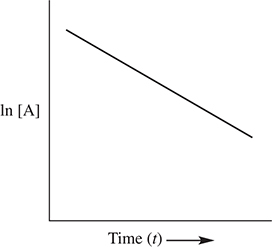

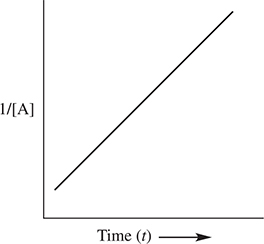

The order of reaction can be determined graphically. If a plot of the ln [A] versus time yields a straight line, then the reaction is first order with respect to reactant A. If a plot of ![]() versus time yields a straight line, then the reaction is second order with respect to reactant A. Finally, if a plot of [A] versus time yields a straight line, the reaction is zero order with respect to reactant A. These plots are shown in Figure 13.2.

versus time yields a straight line, then the reaction is second order with respect to reactant A. Finally, if a plot of [A] versus time yields a straight line, the reaction is zero order with respect to reactant A. These plots are shown in Figure 13.2.

Figure 13.2 Integrated rate law plots.

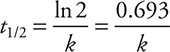

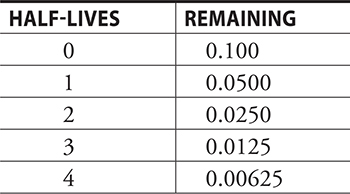

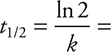

The reaction half-life, t1/2, is the amount of time that it takes for a reactant concentration to decrease to one-half its initial concentration. For a first-order reaction, the half-life is a constant, independent of reactant concentration, and can be shown to have the following mathematical relationship:

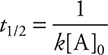

For second-order reactions, the half-life does depend on the reactant concentration and can be calculated using the following formula:

For zero-order reactions, the half-life equation is:

This means that as a second-order or a zero-order reaction proceeds, the half-life changes. However, neither second-order nor zero-order half-life equations are required for the AP Exam.

As mentioned previously, radioactive decay is a first-order process, and the half-lives of the radioisotopes are well documented (see Chapter 18, Nuclear Chemistry, for further discussion of half-lives with respect to nuclear reactions).

If you are unsure about your work in any kinetics problems, just follow your units.

For example, you are asked for time, so your answer must have time units only and no other units. Many people make the error of assuming s—1 or min—1 are time units.

Reaction Energy Profile

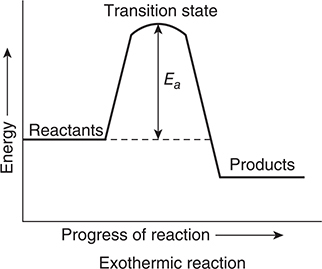

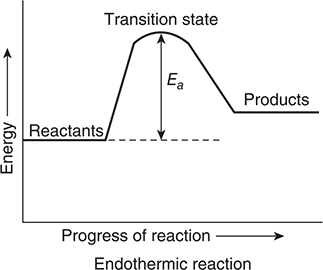

It is possible to represent the progress of a chemical reaction by plotting a reaction energy profile. There are two types of reaction energy profiles, both of which are illustrated in Figure 13.3. In an exothermic profile, the products are lower in energy than are the reactants. In an endothermic profile, the products are higher energy than the reactants. The difference in the energies of the reactants and products is the heat of reaction. The energy profile indicates that for the reactants to get to the products (progressing from left to right on the profile) they must pass through a transition state, sometimes called an activated complex. The transition state is an intermediate form with both characteristics of reactants and products. The difference in energy between the reactants and the transition state is the activation energy, Ea. One of the requirements of an effective collision is that it has an energy that is equal to, or greater than, the activation energy. The greater the activation energy, the slower the reaction.

Figure 13.3 Two different reaction energy profiles.

The activation energy may be related to the rate constant for the reaction by the Arrhenius equation. However, the AP Exam does not assess calculations involving the Arrhenius equation.

Activation Energy

A change in the temperature at which a reaction is taking place will affect the rate constant k. As the temperature increases, the value of the rate constant increases and the reaction goes faster. (A rate constant is only constant if the temperature is constant.) The Swedish scientist Arrhenius derived a relationship in 1889 that related the rate constant and temperature. The Arrhenius equation has the form: ![]() where k is the rate constant, A is a term called the frequency factor that accounts for molecular orientation, e is the natural logarithm base, R is the universal gas constant 8.314 J mol K—1, T is the Kelvin temperature, and Ea is the activation energy, the minimum amount of energy that is needed to initiate or start a chemical reaction.

where k is the rate constant, A is a term called the frequency factor that accounts for molecular orientation, e is the natural logarithm base, R is the universal gas constant 8.314 J mol K—1, T is the Kelvin temperature, and Ea is the activation energy, the minimum amount of energy that is needed to initiate or start a chemical reaction.

The Arrhenius equation is most commonly used to calculate the activation energy of a reaction. One way this can be done is to plot the ln k versus 1/T. This gives a straight line whose slope is —Ea/R. Knowing the value of R allows the calculation of the value of Ea.

Normally, high activation energies are associated with slow reactions. Anything that can be done to lower the activation energy of a reaction will tend to speed up the reaction.

Reaction Mechanisms

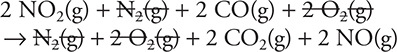

In the introduction to this chapter, we discussed how chemical reactions occurred. Recall that before a reaction can occur there must be a collision between one reactant with the proper orientation at the reactive site of another reactant that transfers enough energy to provide the activation energy. However, many reactions do not take place in quite this simple a way. Many reactions proceed from reactants to products through a sequence of reactions. This sequence of reactions is called the reaction mechanism. For example, consider the reaction:

A + 2B → E + F

Most likely, E and F are not formed from the simple collision of an A and two B molecules. This reaction might follow this reaction sequence:

A + B → C

C + B → D

D → E + F

If you add together the three equations above, you will get the overall equation A + 2B → E + F. C and D are called reaction intermediates, chemical species that are produced and consumed during the reaction but that do not appear in the overall reaction.

Each individual reaction in the mechanism is called an elementary step or elementary reaction. Each reaction step has its own rate of reaction. One of the reaction steps is slower than the rest and is the rate-determining step. The rate-determining step limits how fast the overall reaction can occur. Therefore, the rate law of the rate-determining step is the rate law of the overall reaction.

The rate equation for an elementary step can be determined from the reaction stoichiometry, unlike the overall reaction. The reactant coefficients in the elementary step become the reaction orders in the rate equation for that elementary step.

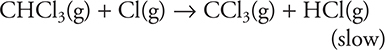

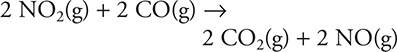

Many times a study of the kinetics of a reaction gives clues to the reaction mechanism. For example, consider the following reaction:

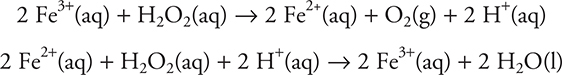

![]()

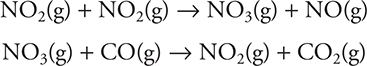

It has been determined experimentally that the rate law for this reaction is: Rate = k[NO2]2. This rate law indicates that the reaction does not occur with a simple collision between NO2 and CO. A simple collision of this type would have a rate law of Rate = k[NO2][CO]. The following mechanism has been proposed for this reaction:

Notice that if you add these two steps together, you get the overall reaction. The first step has been shown to be the slow step in the mechanism, the rate-determining step. If we write the rate law for this elementary step, it is: Rate = k[NO2]2, which is identical to the experimentally determined rate law for the overall reaction.

Also note that both steps in the mechanism are bimolecular reactions, reactions that involve the collision of two chemical species. In unimolecular reactions, a single chemical species decomposes or rearranges. Both bimolecular and unimolecular reactions are common, but the collision of three or more chemical species is quite rare. Therefore, in developing or assessing a mechanism, it is best to consider only unimolecular or bimolecular elementary steps.

Steady-State Approximation

In multistep reactions it is not always easy to determine the rate law. This is especially true when the first step in the mechanism is not the rate-determining step. In these cases, the steady-state approximation may be used to derive the rate law. This method assumes that one of the intermediates in the mechanism reacts as quickly as it was generated, thus its concentration remains constant throughout the reaction.

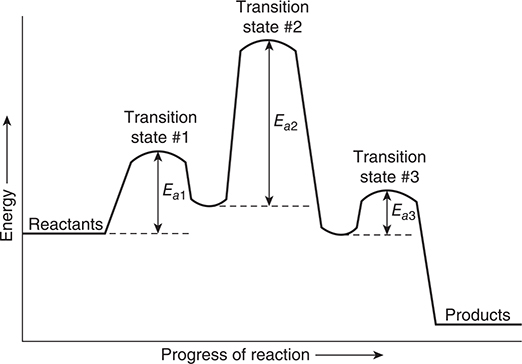

Multistep Reaction Energy Profile

The reaction energy profiles shown in Figure 13.3 are for single-step reactions. However, some reactions require more than one step. The reaction energy profiles for multistep reactions are different than those for single-step reactions. Figure 13.4 shows the energy profile for a three-step exothermic reaction. Each step has its own transition state and activation energy, which are labelled in the figure. Notice that in the figure, one activation energy (Ea2) is greater than the other two, which means that this is the rate-determining step.

Figure 13.4 A reaction energy profile for a three-step reaction. Each step has its own transition state and activation energy.

Catalysts

A catalyst is a substance that speeds up the rate of reaction without being consumed in the reaction. A catalyst may take part in the reaction and even be changed during the reaction, but at the end of the reaction, it is at least theoretically recoverable in its original form. It will not produce more of the product, but it allows the reaction to proceed more quickly. In equilibrium reactions (see Chapter 15, Equilibrium), the catalyst speeds up both the forward and reverse reactions. Catalysts speed up the rates of reaction by providing a different mechanism that has a lower activation energy or by increasing the number of effective collisions. The higher the activation energy of a reaction, the slower the reaction will proceed. Catalysts provide an alternative pathway that has a lower activation energy and thus will be faster. In general, there are two distinct types of catalyst: homogeneous catalysts and heterogeneous catalysts. Often the catalyst forms a bond to one or more reactants. If no bond forms, the binding is due to intermolecular forces. The formation of the bond or the interactions from intermolecular forces often distort a reactant to increase the probability of an effective collision or lowering the activation energy.

Homogeneous Catalysts

Homogeneous catalysts are catalysts that are in the same phase or state of matter as the reactants. They provide an alternative reaction pathway (mechanism) with a lower activation energy.

The decomposition of hydrogen peroxide is a slow, one-step reaction, especially if the solution is kept cool and in a dark bottle:

![]()

However, if ferric ion is added, the reaction speeds up tremendously. The proposed reaction sequence for this new reaction is:

Notice that in the reaction the catalyst, Fe3+, was reduced to the ferrous ion, Fe2+, in the first step of the mechanism, but in the second step it was oxidized back to the ferric ion. Overall, the catalyst remained unchanged. Notice also that although the catalyzed reaction is a two-step reaction, it is significantly faster than the original uncatalyzed one-step reaction. You should also note that this is the “proposed mechanism”; experimental evidence suggests what a mechanism may be, but such evidence can never prove a mechanism.

Heterogeneous Catalysts

A heterogeneous catalyst is in a different phase or state of matter from the reactants. Most commonly, the catalyst is a solid and the reactants are liquids or gases. These catalysts lower the activation energy for the reaction by providing a surface for the reaction and by providing a better orientation of one reactant, so its reactive site is more easily hit by the other reactant. Many times these heterogeneous catalysts are finely divided metals. The Haber process, by which nitrogen and hydrogen gases are converted into ammonia, depends upon an iron catalyst, while the hydrogenation of vegetable oil to margarine uses a nickel catalyst.

Experiments

Unlike other experiments, a means of measuring time is essential to all kinetics experiments. This may be done with a clock or a timer. The initial concentration of each reactant must be determined. Often this is done through a simple dilution of a stock solution. The experimenter must then determine the concentration of one or more substances later or record some measurable change in the solution. Unless there will be an attempt to measure the activation energy, the temperature should be kept constant. A thermometer is needed to confirm this.

“Clock” experiments are common kinetics experiments. They do not require a separate experiment to determine the concentration of a substance in the reaction mixture. In clock experiments, after a certain amount of time, the solution suddenly changes color. This occurs when one of the reactants has disappeared, and another reaction involving a color change can begin.

In other kinetics experiments, the volume or pressure of a gaseous product is monitored. Again, it is not necessary to analyze the reaction mixture. Color changes in a solution may be monitored with a spectrophotometer. Finally, as a last resort, a sample of the reaction mixture may be removed at intervals and analyzed.

The initial measurement and one or more later measurements are required. (Remember: you measure times; you calculate changes in time [Δt]). Glassware, for mixing and diluting solutions, and a thermometer are the equipment needed for a clock experiment. Other kinetics experiments will use additional equipment to measure volume, temperature, etc. Do not forget: in all cases, you measure a property and then calculate a change. You never measure a change.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

1. When working mathematical problems, be sure your units cancel to give you the desired unit in your answer.

2. Be sure to round your answer off to the correct number of significant figures.

3. In working rate law problems, be sure to use molarity for your concentration unit.

4. In writing integrated rate laws, be sure to include the negative sign with the change in reactant concentration since it will be decreasing with time.

5. Remember that the rate law for an overall reaction must be derived from experimental data.

6. In mathematically determining the rate law, be sure to set up the ratio of two experiments such that the concentration of only one reactant has changed.

7. Remember that in most of these calculations the base e logarithm (ln) is used and not the base 10 logarithm (log).

8. Students not understanding what a catalyst is have made numerous errors. A catalyst is never used up in a reaction.

![]() Review Questions

Review Questions

Use these questions to review the content of this chapter and practice for the AP Chemistry Exam. First are 20 multiple-choice questions similar to what you will encounter in Section I of the AP Chemistry Exam. There are some questions present to help you review prior knowledge. Following those is a long free-response question like the ones in Section II of the exam. To make these questions an even more authentic practice for the actual exam, time yourself following the instructions provided.

Multiple-Choice Questions

Answer the following questions in 30 minutes. You may use the periodic table and the equation sheet at the back of this book.

1. A reaction follows the rate law Rate = k[A]2. Which of the following plots will give a straight line?

(A) 1/[A] versus 1/time

(B) [A]2 versus time

(C) 1/[A] versus time

(D) ln [A] versus time

2. For the reaction NO2(g) + CO(g) → NO(g) + CO2(g), the rate law is Rate = k[NO2]2. If a small amount of gaseous carbon monoxide (CO) is added to a reaction mixture that was 0.10 molar in NO2 and 0.20 molar in CO, which of the following statements is true?

(A) Both k and the reaction rate remain the same.

(B) Both k and the reaction rate increase.

(C) Both k and the reaction rate decrease.

(D) Only k increases; the reaction rate will remain the same.

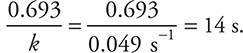

3. The specific rate constant, k, for radioactive beryllium-11 is 0.049 s—1. What mass of a 0.500-mg sample of beryllium-11 remains after 28 seconds?

(A) 0.250 mg

(B) 0.125 mg

(C) 0.0625 mg

(D) 0.375 mg

4. The rate of reaction for a certain chemical is slow. A possible cause of the slow rate might be which of the following?

(A) The activation energy is low.

(B) The activation energy is high.

(C) There is a catalyst present.

(D) There was an increase in the temperature.

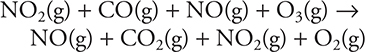

5. The steps below represent a proposed mechanism for the catalyzed oxidation of CO by O3.

Step 1: NO2(g) + CO(g) → NO(g) + CO2(g)

Step 2: NO(g) + O3(g) → NO2(g) + O2(g)

What are the overall products of the catalyzed reaction?

(A) CO2 and O2

(B) NO and CO2

(C) NO2 and O2

(D) NO and O2

6. The decomposition of ammonia to the elements is a first-order reaction with a half-life of 200 s at a certain temperature. How long will it take the partial pressure of ammonia to decrease from 0.100 atm to 0.00625 atm?

(A) 200 s

(B) 400 s

(C) 800 s

(D) 1,000 s

7. The energy difference between the reactants and the transition state is:

(A) the free energy

(B) the heat of reaction

(C) the activation energy

(D) the kinetic energy

8. Which of the following is the reason it is necessary to strike a match against the side of a box to light the match?

(A) It is necessary to supply the free energy for the reaction.

(B) It is necessary to supply the activation energy for the reaction.

(C) It is necessary to supply the heat of reaction for an endothermic reaction.

(D) It is necessary to supply the heat of reaction for an exothermic reaction.

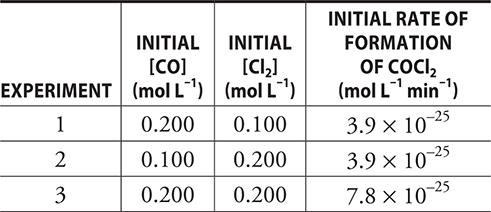

9. The following table gives the initial concentrations and rate for three experiments.

The reaction is CO(g) + Cl2(g) → COCl2(g). What is the rate law for this reaction?

(A) Rate = k[CO]

(B) Rate = k[CO]2 [Cl2]

(C) Rate = k[CO][Cl2]

(D) Rate = k[CO][Cl2]2

10. The reaction (CH3)3CBr(aq) + H2O(l) → (CH3)3COH(aq) + HBr(aq) follows the rate law Rate = k[(CH3)3CBr]. What will be the effect of decreasing the concentration of (CH3)3CBr?

(A) The rate of the reaction will increase.

(B) More HBr will form.

(C) The rate of the reaction will decrease.

(D) The reaction will shift to the left.

11. When the concentration of H+(aq) is doubled for the reaction H2O2(aq) + 2 Fe2+(aq) + 2 H+(aq) → 2 Fe3+(aq) + 2 H2O(g), there is no change in the reaction rate. This indicates that:

(A) the H+ is a spectator ion

(B) the rate-determining step does not involve H+

(C) the reaction mechanism does not involve H+

(D) the H+ is a catalyst

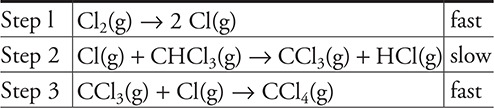

12. The following mechanism has been proposed for the reaction of CHCl3 with Cl2:

Which of the following rate laws is consistent with this mechanism?

(A) Rate = k[Cl2]

(B) Rate = k[CHCl3][Cl2]

(C) Rate = k[CHCl3]

(D) Rate = k[CHCl3][Cl2]1/2

13. The reaction NO2(g) + CO(g) → NO(g) + CO2(g) has the rate law Rate = k[NO2]2. In one experiment, the initial amounts of NO2 and CO were both 0.100 M. In another experiment, the initial concentration of CO was doubled to 0.200 M, and the concentration of NO2 remained the same (0.100 M). All other variables remained unchanged. Which of the following expresses how the rate of the second experiment compares to that of the first experiment?

(A) The rate of both experiments is the same.

(B) The rate of the second experiment is double the first.

(C) The rate of the second experiment is one-half the first.

(D) There is insufficient information to make a conclusion.

14. The rate law for the following reaction is Rate = k[H2][I2]. The reaction is H2(g) + I2(g) → 2 HI(g). A chemist studying this reaction prepared what he thought was a mixture that was 0.10 M in H2 and 0.20 M in I2. In reality, the mixture had a slightly higher I2 concentration. All other reaction conditions were correct. Because of the error, the experiment did not proceed exactly as expected. Which of the following statements is true about the actual experiment (higher I2) relative to the experiment the chemist thought he was performing (expected I2)?

(A) The values of k and the reaction rate both decreased.

(B) The values of k and the reaction rate both increased.

(C) The value of the rate increased, but k remained the same.

(D) The value of k increased, but the reaction rate remained the same.

15. Step 1: 2 NO2(g) → N2(g) + 2 O2(g)

Step 2: 2 CO(g) + O2(g) → 2 CO2(g)

Step 3: N2(g) + O2(g) → 2 NO(g)

The above is a proposed mechanism for the reaction of NO2 and CO. What are the overall products of the reaction?

(A) NO and CO2

(B) O2 and CO2

(C) N2 and NO

(D) NO and O2

16. The reaction of bromine, Br2, with nitrogen oxide, NO, is Br2(g) + 2 NO(g) → 2 NOBr(g).

For this reaction, the observed rate law is Rate = k [Br2] [NO]2. Why is the following step unlikely to be in the mechanism?

Br2(g) + 2 NO(g) → 2 NOBr(g)

(A) NO is an unstable molecule.

(B) Br2 is too stable to react.

(C) This is a ternary step.

(D) This could be a step in the mechanism.

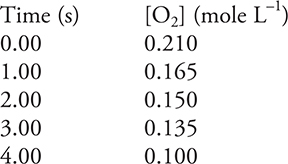

Use the following information to answer Question 17.

![]()

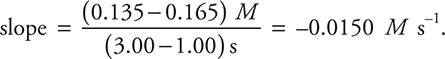

17. An environmental chemist investigates the above reaction and obtains the data listed in the above table. Which of the following is the rate between 1.00 and 3.00 seconds?

(A) —0.0450 M s—1

(B) —0.0217 M s—1

(C) —0.0150 M s—1

(D) —0.0275 M s—1

Use the following information to answer Questions 18 and 19.

![]()

The proposed mechanism for the above reaction is as follows:

Step 1: ![]()

Step 2:

Step 3: ![]()

18. The reaction energy profile for the above reaction will have how many peaks?

(A) 3

(B) 1

(C) 2

(D) 4

19. What are possible units for the rate constant for the above reaction?

(A) It would have no units.

(B)

(C)

(D)

20. The decomposition reaction of KClO3(s) is catalyzed by MnO2(s). The reaction produces KCl(s) and O2(g). In one experiment 12.24 g of KClO3(s) and 0.87 g of MnO2(s) are used, and 9.60 g of O2(g) are produced. In second experiment, the mass of KClO3(s) is halved and the mass of MnO2(s) is kept the same (0.87 g). In the second experiment, the mass of O2(g) produced is one-half that in the first experiment. In a third experiment, 12.24 g of KClO3(s) and one-half the grams of MnO2(s) are used, how does the mass of O2(g) produced in the third experiment compare to the mass of O2(g) in the first experiment?

Molar masses (in g mol—1)

KClO3 = 122.4, MnO2 = 86.94, O2 = 32.00, KCl = 74.55

(A) 4.80 g O2(g)

(B) 9.60 g O2(g)

(C) 19.20 g O2(g)

(D) 9.26 g O2(g)

![]() Answers and Explanations

Answers and Explanations

1. C—The exponent 2 means this is a second-order rate law. Second-order rate laws give a straight-line plot for 1/[A] versus t. D applies to first-order reactions. A and B do not apply to any reaction.

2. A—The value of k remains the same unless the temperature is changed or a catalyst is added. Only materials that appear in the rate law, in this case NO2, will affect the rate. Adding NO2 would increase the rate and removing NO2 would decrease the rate. CO has no effect on the rate.

3. B—The half-life is  (It is possible to get this answer by rounding the values to 0.7/0.05 s—1.) The time given, 28 s, represents two half-lives. The first half-life uses one-half of the beryllium, and the second half-life uses one-half of the remaining material, so only one-fourth of the original material remains

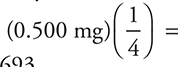

(It is possible to get this answer by rounding the values to 0.7/0.05 s—1.) The time given, 28 s, represents two half-lives. The first half-life uses one-half of the beryllium, and the second half-life uses one-half of the remaining material, so only one-fourth of the original material remains  = 0.125 mg. The relationship

= 0.125 mg. The relationship  is given on the AP Exam. This may be mistaken for a nuclear chemistry problem. Remember, radioactive decay processes are amongst the best examples of first-order kinetics, and all first-order kinetics equation apply.

is given on the AP Exam. This may be mistaken for a nuclear chemistry problem. Remember, radioactive decay processes are amongst the best examples of first-order kinetics, and all first-order kinetics equation apply.

4. B—Slow reactions have high activation energies. Low activation energies (A) are typical of fast reactions. A catalyst (C) will increase the rate of a reaction. Increasing the temperature (D) will increase the rate of a reaction.

5. A—Add the two equations together:

Then cancel identical species that appear on opposite sides:

![]()

The NO2(g) cancels because it is the catalyst.

6. C—The value will be decreased by one-half for each half-life. Using the following table:

Four half-lives = 4(200 s) = 800 s

This answer may also be determined using the following two equations that are given on the AP Exam:  .

.

7. C—This is the definition of the activation energy.

8. B—The friction supplies the energy necessary to start the reaction. This energy is the activation energy. The free energy and the heat of reaction for the reaction deal with the reactants and products. It is necessary to deal with the reactants and transition state (activated complex), which are separated by the activation energy.

9. C——Beginning with the generic rate law, Rate = k[CO]m [Cl2]n, it is necessary to determine the values of m and n (the orders). Comparing Experiments 2 and 3, note that the rate doubles when the concentration of CO is doubled. This direct change means the reaction is first order with respect to CO. Comparing Experiments 1 and 3, note that the rate doubles when the concentration of Cl2 is doubled. Again, this direct change means the reaction is first order. This gives Rate = k[CO] [Cl2].

10. C—The compound appears in the rate law, so a change in its concentration will change the rate. The reaction is first order in (CH3)3CBr, so the rate will change directly with the change in concentration of this reactant. Do not be distracted because this is an organic compound.

11. B—All substances involved, directly or indirectly, in the rate-determining step will change the rate when their concentrations are changed. The ion is required in the balanced chemical equation, so it cannot be a spectator ion, and it must appear in the mechanism. Catalysts will change the rate of a reaction. Since H+ does not affect the rate, the reaction is zero order with respect to this ion.

12. D—The rate law depends on the slow step of the mechanism. The reactants in the slow step are Cl and CHCl3 (one of each). The rate law is first order with respect to each of these. The Cl is half of the original reactant molecule Cl2. This replaces the [Cl] in the rate law with [Cl2]1/2. Do not make the mistake of using the overall reaction to predict the rate law.

13. A—Carbon monoxide, CO, does not appear in the rate law. Since it does not appear in the rate law, changing the concentration of CO will not change the rate of the reaction.

14. B—The higher I2 concentration will increase the value of the rate and give a higher apparent k. This k is higher than the true k.

15. A—Add the equations and cancel anything that appears on both sides of the reaction arrows.

Total:

Leaving:

Or: ![]()

16. C—Ternary steps, steps involving three molecules, are very unlikely in mechanisms.

17. C—The rate of the reaction is equal to the slope of the line between the times selected. The slope is ΔM/Δt, which for a reactant, like O2, must be negative. As an example, the slope between the 1.00 and 3.00 seconds is:  The other answers result when the slope is determined between the wrong two points. The slope between the first and last point is —0.0275 M s—1. The slope between the first and second point is —0.0450 M s—1. The slope between the second and last point is —0.0217 M s—1.

The other answers result when the slope is determined between the wrong two points. The slope between the first and last point is —0.0275 M s—1. The slope between the first and second point is —0.0450 M s—1. The slope between the second and last point is —0.0217 M s—1.

We have seen the students picking the wrong two points in a calculation such as this.

18. A—There should be one peak for each step in the mechanism.

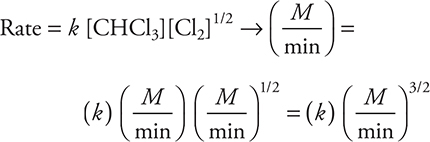

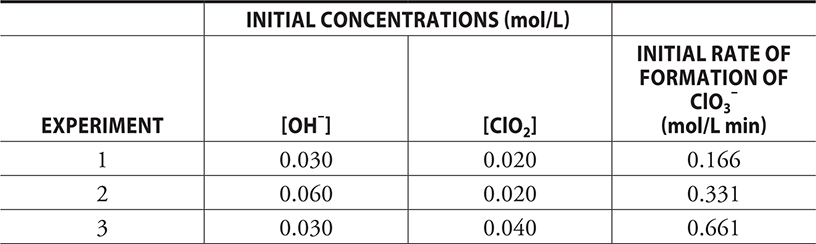

19. B—Note that unlike many rate constants which use seconds as the time unit, the rate constants here use minutes as the time unit, which is acceptable.

To begin solving the problem you will need the rate law for the reaction. The rate law comes from the rate determining (slow) step and is: ![]() . The first choice comes directly from the slow step, which must be changed to the second as the rate law must use the reactants from the overall reaction and not an equation containing any reaction intermediates (Cl). Adding units to the rate law gives:

. The first choice comes directly from the slow step, which must be changed to the second as the rate law must use the reactants from the overall reaction and not an equation containing any reaction intermediates (Cl). Adding units to the rate law gives:

The units on both sides of the rate law equation must be identical, and if they are not, the units on the rate constant will correct the inconsistency. Therefore:

20. B—Catalysts change the rate of the reaction not the overall yield. So changing the quantity of catalyst (other than to 0) will not alter the yield.

![]() Free-Response Question

Free-Response Question

You have 15 minutes to answer the following long question. You may use a calculator and the tables in the back of the book.

Question

![]()

A series of experiments were conducted to study the above reaction. The following table provides the initial concentrations and rates.

(a) (i) Determine the order of the reaction with respect to each reactant. Make sure to explain your reasoning.

(ii) Give the rate law for the reaction.

(b) Determine the value of the rate constant, making sure to include the units.

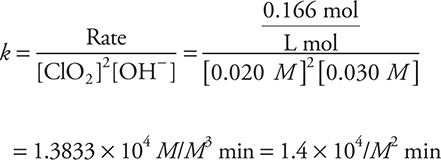

(c) Calculate the initial rate of disappearance of ClO2 in Experiment 1.

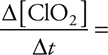

(d) The following is the proposed mechanism for this reaction:

Step 1: ClO2(aq) + ClO2(aq) → Cl2O4(aq)

Step 2: Cl2O4(aq) + OH—(aq) → ClO3—(aq) + HClO2(aq)

Step 3: HClO2(aq) + OH—(aq) → ClO2—(aq) + H2O(l)

Which step is the rate-determining step? Show that this mechanism is consistent with both the rate law for the reaction and with the overall stoichiometry.

![]() Answer and Explanation

Answer and Explanation

(a) (i) This part of the problem begins with a generic rate equation: Rate = k[ClO2]m [OH—]n. The values of the exponents, the orders, must be determined. It does not matter which exponent is done first. If you want to begin with ClO2, you must pick two experiments from the table in which the concentration of ClO2 changes but the OH— concentration does not change. These are Experiments 1 and 3. Experiment 3 has twice the concentration of ClO2 as Experiment 1. This doubling of the ClO2 concentration has quadrupled the rate. The relationship between the concentration (× 2) and the rate (× 4 = × 22) indicates that the order for ClO2 is 2 (= m). Using Experiments 1 and 2 (in which only the OH— concentration changes), we see that doubling the concentration simply doubles the rate. Thus, the order for OH— is 1 (= n).

Give yourself 1 point for each order you got correct, for a maximum of 2 points.

(ii) Inserting the orders into the generic rate law gives Rate = k[ClO2]2 [OH—]1, which is usually simplified to Rate = k[ClO2]2 [OH—].

Give yourself 1 point if you got this equation correct. If you got the wrong answer for part (a) (i) but used it correctly here, you still get 1 point.

(b) Any one of the three experiments may be used to calculate the rate constant. If the problem asked for an average rate constant, you would need to calculate a value for each of the experiments and then average the values.

The rate law should be rearranged to  . Then, the appropriate values are entered into the equation. Using Experiment 1 as an example,

. Then, the appropriate values are entered into the equation. Using Experiment 1 as an example,

The answer could also be reported as 1.4 × 104 L2/mol2 min. You should not forget that M = mol/L.

Give yourself 1 point for the correct numerical value. Give yourself 1 point for the correct units. If you had the wrong rate law in part (a) (ii) but used it correctly in part (b), you can still get one or both points.

(c) The coefficients from the equation say that for every mole of ClO3— that forms, 2 moles of ClO2 react. Thus, the rate of ClO2 is twice the rate of ClO3—. Do not forget that since ClO3— is forming, it has a positive rate, and since ClO2 is reacting, it has a negative rate. Rearranging and inserting the rate from Experiment 1 gives  —2(0.166 mol/L min)] = —0.332 mol/L min.

—2(0.166 mol/L min)] = —0.332 mol/L min.

Give yourself 2 points if you got the entire answer correct. You get only 1 point if the sign or units are missing or incorrect.

(d) The rate-determining step must match the rate law. One approach is to determine the rate law for each step in the mechanism. This gives the following:

Step 1: ![]()

Step 2: ![]()

Step 3: ![]()

For steps 2 and 3, it is necessary to replace the intermediates with reactants. Step 2 gives a rate law matching the one derived in part (a).

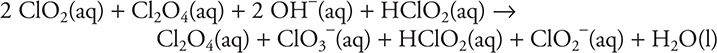

To see if the stoichiometry is correct, simply add the three steps together and cancel the intermediates (materials that appear on both sides of the reaction arrow).

Step 1: ![]()

Step 2: ![]()

Step 3: ![]()

Total:

After removing the intermediates (Cl2O4 and HClO2):

![]()

As this matches the original reaction equation, the mechanism fulfills the overall stoichiometry requirement.

Give yourself 1 point if you picked step 2, or if you picked a step with a rate law that matches your wrong answer for part (a). Give yourself 1 more point if you explained the substitution of reactants for intermediates. Give yourself 1 point for summing the equations and proving the overall equation is consistent.

Total your points. There are 10 points possible. Subtract 1 point if any numerical answer has an incorrect number of significant figures.

![]() Rapid Review

Rapid Review

• Kinetics is the study of the speed of a chemical reaction.

• The five factors that can affect the rates of chemical reaction are the nature of the reactants, the temperature, the concentration of the reactants, the physical state of the reactants, and the presence/absence of a catalyst.

• The rate equation relates the speed of reaction to the concentration of reactants and has the form: Rate = k[A]m[B ]n . . . where k is the rate constant and m and n are the orders of reaction with respect to that specific reactant.

• The rate law must be determined from experimental data. Review how to determine the rate law from kinetics data.

• When mathematically comparing two experiments in the determination of the rate equation, be sure to choose two in which all reactant concentrations except one remain constant.

• Rate laws can be written in the integrated form.

• If a reaction is first order, it has the rate law of Rate = k[A]; ln [A]t — ln [A]0 = —kt; a plot of ln [A] versus time gives a straight line.

• If a reaction is second order, it has the form of Rate = k[A]2;  (integrated rate law); a plot of

(integrated rate law); a plot of ![]() versus time gives a straight line.

versus time gives a straight line.

• If a reaction is zero order, it has the rate law of Rate = k[A]0; [A]t — [A]0 = —kt; a plot of [A] versus time gives a straight line.

• The reaction half-life is the amount of time that it takes the reactant concentration to decrease to one-half its initial concentration.

• The half-life for a first-order reaction can be determined by the equation:

If the reaction is not first order, a different equation must be given to you.

If the reaction is not first order, a different equation must be given to you.

• The activation energy is the minimum amount of energy needed to initiate or start a chemical reaction.

• Many reactions proceed from reactants to products by a series of steps called elementary steps. All these steps together describe the reaction mechanism, the pathway by which the reaction occurs.

• The slowest step in a reaction mechanism is the rate-determining step. It determines the rate law.

• A catalyst is a substance that speeds up a reaction without being consumed in the reaction.

• A homogeneous catalyst is in the same phase as the reactants, whereas a heterogeneous catalyst is in a different phase from the reactants.