Numbers: Their Tales, Types, and Treasures.

Chapter 10: Numbers and Proportions

10.4.CREATING RECTANGLES FROM SQUARES

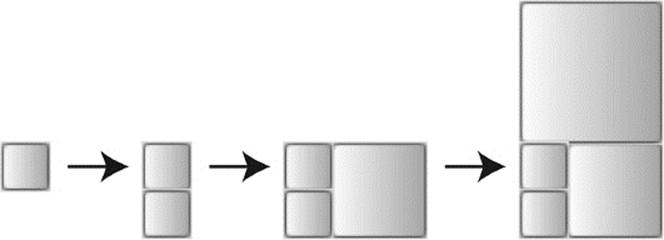

Consider figure 10.5, which shows how to create a rectangular domain from square tiles whose side lengths are a multiple of a common unit. We start with a square with side length 1 and add a second tile of the same size. On the longer side of the resulting rectangle we can place a square with side length 2 to obtain a new, larger rectangle. On its longer side we could fit a square with side length 3. Figure 10.5 should give you an idea of how to proceed. We continue to create larger and larger rectangles by attaching, in each step, a square to the longer side of the rectangle obtained in the previous step.

Figure 10.5

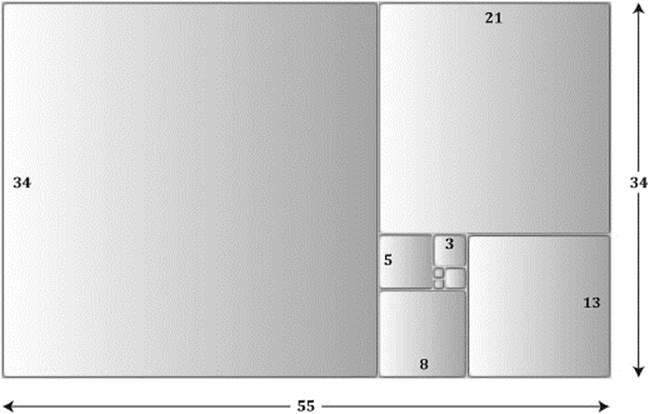

After a few steps, for example, we obtain the rectangle of figure 10.6. It has the proportion 55:34.

Figure 10.6: The Fibonacci numbers forming a golden rectangle.

Looking closely, you may, perhaps, recognize the numbers representing the successive side lengths of the squares. They form the sequence 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34…. We encountered this sequence before, in chapters 5 and 6. These are the Fibonacci numbers Fn, where each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers.

By the way, the area of the rectangle is

12 + 12 + 22 + 32 + 52 + 82 + 132 + 212 + 342 = 34 × 55.

Indeed, this explains the following general formula for the sum of the squares of the Fibonacci numbers and holds for an arbitrary number n of members of the Fibonacci sequence.

The rectangles created successively in figure 10.6 get bigger and bigger, but they seem to have very similar proportions. Looking closely, we see that the smaller rectangle with sides 21 and 13 has a similar shape as the larger rectangle with sides 55 and 34. That is, the proportion 21:13 is approximately the same as 55:34. Indeed, if we evaluate the corresponding quotients numerically, we would obtain ![]() , which is quite close. So we ask the following question: If we would continue the construction of rectangles to obtain larger and larger rectangles whose sides are consecutive Fibonacci numbers, would the proportions of these rectangles become more and more the same? Would the fractions of consecutive Fibonacci numbers

, which is quite close. So we ask the following question: If we would continue the construction of rectangles to obtain larger and larger rectangles whose sides are consecutive Fibonacci numbers, would the proportions of these rectangles become more and more the same? Would the fractions of consecutive Fibonacci numbers

approach a certain value when n gets larger? Table 10.1 shows the first fifteen values.

|

Proportion |

(Approx.) Value |

|||

|

a1 |

1:1 |

1.000000 |

||

|

a2 |

2:1 |

2.000000 |

||

|

a3 |

3:2 |

1.500000 |

||

|

a4 |

5:3 |

1.666667 |

||

|

a5 |

8:5 |

1.600000 |

||

|

a6 |

13:8 |

1.625000 |

||

|

a7 |

21:13 |

1.615385 |

||

|

a8 |

34:21 |

1.619048 |

||

|

a9 |

55:34 |

1.617647 |

||

|

a10 |

89:55 |

1.618182 |

||

|

a11 |

144:89 |

1.617978 |

||

|

a12 |

233:144 |

1.618056 |

||

|

a13 |

377:233 |

1.618026 |

||

|

a14 |

610:377 |

1.618037 |

||

|

a15 |

987:610 |

1.618033 |

Table 10.1: Ratios of consecutive Fibonacci numbers.

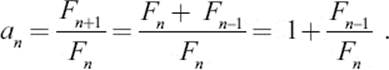

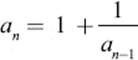

From the numbers in the last column in table 10.1 it appears that the sequence of the an values indeed approaches a certain value for large n. This value is close to 1.618. We are going to denote this limiting value ϕ (the Greek letter phi). From the property of the Fibonacci sequence, namely Fn+1 = Fn + Fn–1, we can learn more about this number ϕ.

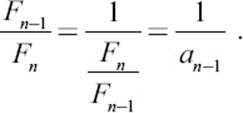

Next we will write the last summand, using the definition of the an, as

Inserting this into the formula above, we obtain the following formula for an:

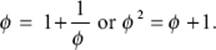

and when n is so large that both an and an–1 are approximately equal to their limit ϕ, we can infer that the number ϕ must satisfy the relation

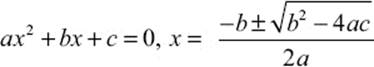

The mathematically inclined reader will probably know how to solve this equation using the formula for the solution of the general quadratic equation

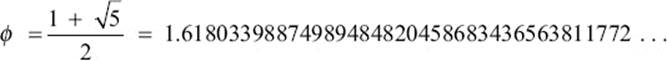

The positive solution is

The sequence of numbers behind the decimal point would not terminate, hence the number is usually rounded off as

ϕ ≈ 1.618.

The number ϕ is one of the most famous numbers in mathematics; it is known as the golden ratio.